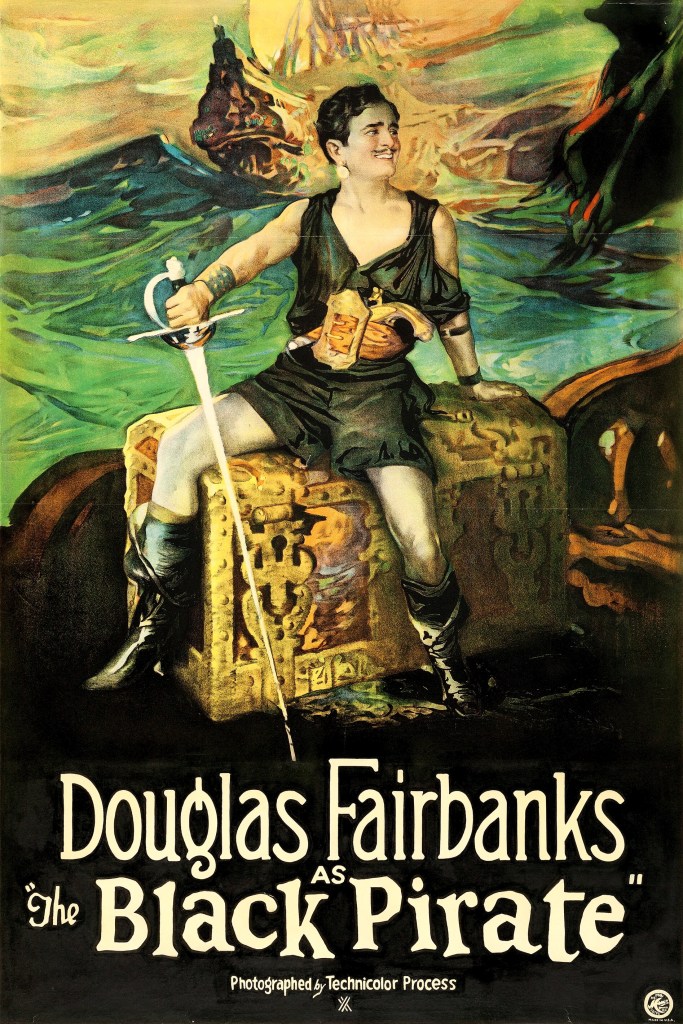

This week, I can report on my first film concert of 2026! After a couple of days of archival rummaging in Berlin (of which, more anon), I took the train south to Nuremberg. My goal was the Kongresshalle, where the Nürnberger Symphoniker have their rehearsal space and one of their main performance venues. The composer and conductor Robert Israel had invited me to attend one of the rehearsals before the performance of The Black Pirate, then the first of two concerts being performed at the end of the week. Though I had listened to any number of the scores Israel has played, arranged, and/or composed for silent films, I had never actually had the chance to experience his music live – nor to see him conduct an orchestra.

I was excited by this prospect, but also to see The Black Pirate again. I knew the film only from the old 1995 restoration, which has been released on various home media releases – the latest version being on Blu-ray by Cohen. However, the version of The Black Pirate that I was seeing in Nuremberg was an entirely new restoration undertaken by the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and The Film Foundation, completed in 2023. For this version, restorers examined and scanned multiple negatives of the two-strip Technicolor, discovering supposedly “lost” prints in the process. After realigning the original green and red elements to make the image as stable as possible, they also checked the resulting colours against a surviving test reel and production records to match as closely as possible the look of the original film. Missing intertitles were restored, and – a century after its initial release – The Black Pirate is back to something very close to its former self.

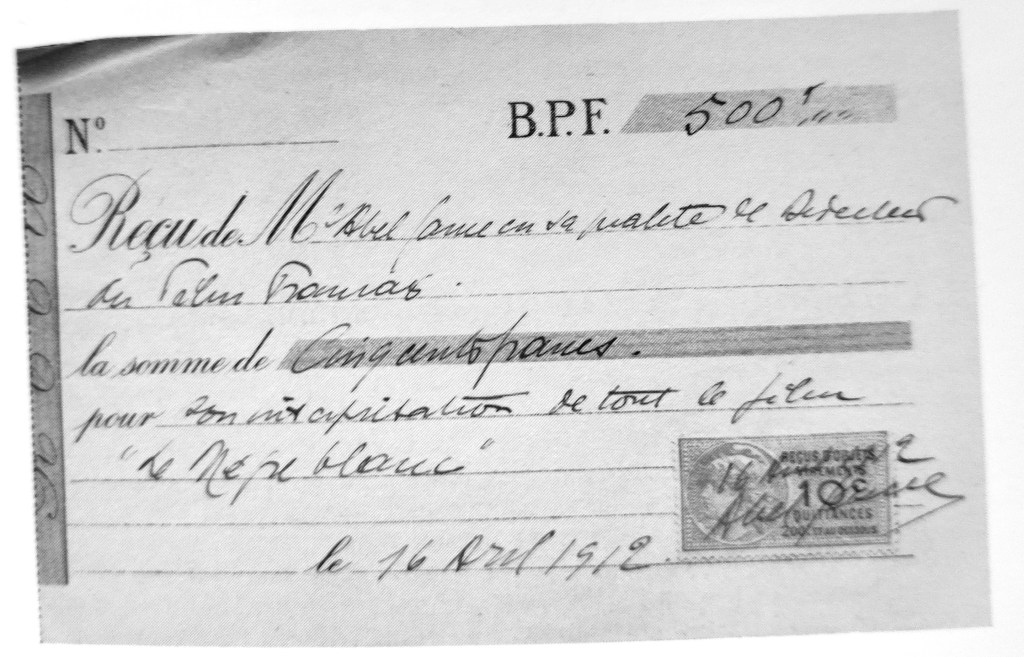

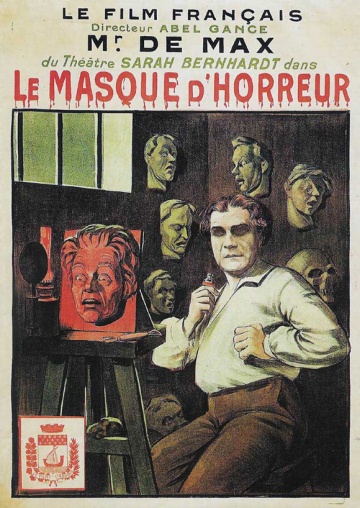

MoMA also commissioned an original orchestral score from Robert Israel. The Black Pirate was originally shown with music by Mortimer Wilson, though the result displeased Fairbanks and he never worked with this composer again. Though I am a fan of Wilson’s score for The Thief of Bagdad (1924), I was somewhat underwhelmed with his music for The Black Pirate. You can hear it, as arranged and recorded by Israel himself, on previous media releases of the 1995 restoration. (I note that the recent Cohen release has cut all information about the soundtrack and its context. Thus, there is no credit to the composer of the music – only to Israel’s role as conductor. One must glance back at Kino’s previous release to see the details.) As I was to glean during the next two days, Israel’s 1996 recording of the Wilson score was a rushed affair that hadn’t been given the time (i.e. budget) to do much with the music. Israel’s new, original score for the 2023 restoration is thus a return to his work for The Black Pirate – and a chance to do the film justice.

Thursday, 29 January 2026: Kongresshalle, Nuremberg

It is snowing heavily, and the streets of Nuremberg are a slippery mass of ice and sludge. Robert Israel has warned me that “time will not be an ally” today. I meet him at his hotel, and he guides our taxi driver to the back entrance of the Kongresshalle. Though this hall is part of a much larger structure (a vast arena built by the Nazis for future rallies), I barely glimpse the building before we enter. From the bustle of the city and the traffic, inside it is remarkably calm and spacious. Israel greets various members of the Symphoniker team, and we negotiate various doors to his room. There, we talk about our journeys through the wintry landscapes to get to Nuremberg (I from Berlin, he from the Czech Republic). In the wake of multiple delays en route, in Nuremberg Israel has only three rehearsals and a final run-through with the orchestra. Ideally, there would be more, but the musicians of the Nürnberger Symphoniker (as I will witness) are quick learners. And Israel has as much experience of this kind of work as anyone alive today (and more than most). This is a man who has spent over forty years performing and writing music for silent cinema. To illustrate a point about his score, he opens his laptop and navigates through dozens of clips and recordings, assembled for work and for teaching. Israel shows me the opening of The Black Pirate, accompanied by a recording of his music, to set the scene. The seeds of the entire score are laid out: characters and ideas are introduced through a series of motifs, while the very mood and spirit of the drama is apparent in the sheer fun and drive of the music. He talks about his previous experience of the film, of Wilson’s score, and the pressures of time. Just then, a head pops round the door and a man informs Israel that some schoolchildren have been invited to watch the orchestra rehearse this morning. (This wonderful scheme with local schools seems to be a fixture of early life in Nuremberg. I’d love to have had this kind of experience when I was young.)

Soon, it’s time to go. With time so limited, there isn’t a moment to waste. I hurry after Israel, who leads me downs some steps, through large double doors, and up onto the back of the stage. (For someone always in the wings, it’s a sneaky thrill for me to tread, however briefly, on stage.) The orchestra has started to assemble, and I find myself negotiating the little forest of music stands and precious instruments. Israel wends his way to the podium, puts down his bag, and motions me to take a seat in the auditorium. I clamber down the front steps and find a space a couple of rows behind the two ranks of schoolchildren and their teachers. There is a hushed curiosity among these eager kids, who watch – as I do – the players take their seats on stage. The musicians have their own gentle hubbub of voices, soon augmented by the hubbub of instruments warming up. Suspended in the space above the stage, a large screen bears the promise of images. As ever, the players don’t get to see the film in rehearsal and will scarcely have a chance to do so at any point in their two performances. What’s more, these musicians are sight reading Israel’s score as they go. Not seeing the film, and not knowing the score, their performance will be a remarkable feat of skill and discipline. Only Israel, as conductor, will be able to face the screen and keep them in time with the film.

It’s time to begin. Israel turns to the auditorium and (in German) introduces The Black Pirate to the children. This morning’s session will cover the last third of the drama. In a few words, Israel promises us pirates – and adventure. Then he turns to the orchestra, raises his baton, and the floor shakes with the roar of brass. Drums rattle, strings stride… Then, silence. Israel’s baton keeps time amid the pause. The music resumes, but not in time: “Stop! Stop,” he says. “Let’s not lose count. Takt nummer eintausenddreihundertund…”. Watching him mark the silent bar, my attention is drawn to Israel’s arms and shoulders. He’s wearing a black T-shirt to conduct at the rehearsal, and I can see why. It’s a tremendously energetic occupation, a performance in advance of the performance. The clothes – both of conductor and orchestra – are casual, but only in the sense that a tracksuit might be for an athlete. This rehearsal is a workout in more ways than one, and you can sense the physical energy being exuded by these musicians. It’s an odd contrast, this hall and stage, and the few ranks of observers, with the outside world. Through the windows, I can glimpse the snowbound city, entirely white. Inside, we might be watching a sports team practice their routines, such is the energy and bustle on this cold day. (Something about the pale wooden fittings in here reminds me of a sports hall, too.)

On stage, the music is warming up. Here is a swagger in sound, invisible figures strutting on deck. You can hear the gestures. Israel stops. “Molto espressivo, here”. They go again, and the players respond. Phrases that a moment ago were stiff, unstretched are now mellower, have a glow about them. Menacing steps, a sweep of snare drums. […] “Snare and tam-tam. Can you start at mezzo forte, but…” […] A pause. Israel takes on water. A solo violin tries out a phrase, stretches it, smooths it. The sounds cease. Israel speaks again, introducing the next scene: “Fairbanks is walking the plank into the ocean – but he escapes!” The music growls. The waves tremble beneath a funeral march, a march that’s noble, sad, moving – and menacing. Suddenly Israel’s arms reach up, react. Tension – drums… “OK, let’s stop. Let’s do some work on this.”

The work proceeds. Israel addresses a player: “Tam-tam…”. He explains what’s happening on screen, to get the right effect from the instrument. “He goes into the ocean. That’s you!” There is more work, then another note. “First horn. I know it says ‘mezzo forte’, but considering how it sounds here, you’ve coming through so well, you can lower it a bit.” “Oh, I’m sorry”, the player replies. “No, no, it’s perfect”, Israel explains, “It’s just for the acoustics of the hall.” […] Brass and woodwind are taken through their steps separately, then the strings. The sound is by turns nasal, chesty, sensuous, shimmering. Then they go all together, and it’s steady. […] “At this bar, think Scheherazade!” Israel calls out to a player. “That’s you, above the orchestra.” The take proceeds. “Ja!! Super! Dankeschön!” the conductor cries to the timpani, after a grand moment. […] From the combined body of sound, there is a ravishing violin solo. Between takes, Israel calls for a subtler balance of sound: “Think violin concerto. Those dynamics.” Another take. It sounds gorgeous.

(As the musicians continue, the rows of schoolchildren in front of me are gathered up by their teachers and, with gentle pleas for hush, are quietly trouped from the hall. Suddenly, I feel a little conspicuous, sat alone in the audience as the orchestra continues.)

We go again, but – “First horn, from C natural to B natural…”, and Israel sings the right way to shape the phrase. The first violin soars again. […] “Careful after zweitausendvierhundertundsechzig… At the oboe solo… for two bars, we need to be a little more quiet…”, and they go again. “Ja, das ist gut!” […] “So Douglas Fairbanks gets out of the ocean…”. There is some shifting around, a snatch of conversation. A comment I cannot hear earns the response: “If you’re going to steal, steal from the best, right?” […] The orchestra climbs out of the ocean – “Careful, that’s a major chord there. Ja, G-major.” […] “Violins and the bass, let’s not go for mezzo forte, let’s go with mezzo piano, it’s a bit too much.” They go through it again. As this passage ends, Israel’s arms are aloft. It sounded great, and everyone on stage knows it. “Ja!” he cries, and everyone smiles.

The next section. “Fairbanks is riding on horseback…”. There are quick interchanges between this image, and the other half of the scene – which the orchestra cannot see, only feel by the alternation of themes in the music. The swift changes of tempo and tone catch some out. “You need to be very careful here with your count”, Israel reminds them. […] The orchestra goes through once, twice, each time better. The players are learning the score, not just with their intelligence but with their bodies. Music is kinetic, and you can hear the experience of playing being taken on physically. Music is muscle memory, after all. Israel admires their efforts. “Very good reading, this is very tricky…”. They go again. Muscle and flair on stage, like Fairbanks himself on screen. The music roars and shakes itself, and the floor trembles. There are questions, and Israel reassures. “No, that rubato bar is good. I will go to it.”

We move on. “Takt nummer zweitausendsiebenhundertundzwanzig, bitte…”. The orchestra trips a little, then picks itself up, and skips along. […] “Mitternacht…”. Bass clarinet emerges from the cymbal, harp, strings. It sounds beautiful, and it’s being read on sight. Solo violin for a moment. It all sounds gorgeous.

Bar 2777. The solo violin is not so solo. A mistake. “It’s zweitausendsiebenhundertseibenundsiebzig…”. They go again. Menacing rumbling, a gathering swarm in the strings. […] The musicians follow the conductor, who is the intermediary with the unseen film. Since Israel is also the composer, he can explain the rationale for his choices, his rhythms. “Does anyone know morse code?” he asks. Here, Israel stamps out “SOS” on the padded podium floor. It’s the rhythm behind a phrase, and he describes the Princess being in danger of defilement from a pirate. “Let’s hope Douglas Fairbanks arrives in time…!” There is muttering, perhaps a little titter of laughter, but Israel speaks up. “No, this is really a great film. Because in our time, we need to see justice being served. We all deserve that.” The scene in sound plays again. A big climax, and Israel swipes across to bring a halt, then immediately resumes. (I will fully understand this gesture only in the live concert.) […] A long section, everyone in tune, in their groove. A swig of water. It’s hard work, good work. […] Israel talks through the rhythm, taps the floor, sings – bops, rather – a beat. […] “I understand it’s difficult because it’s in your lower register, but it’s very important to get the pulse right.” A long section. “OK, very nice.” And it is!

Israel introduces the next section. “I think you’ll be able to guess who’s showing up with a galley full of soldiers.” It’s vivace, but the going might be tricky. “I think to get used to this, let’s do this in 4, for the notes, then we can go through again in two beats.” They go through, picking up cohesion, swagger even, as they proceed. […] “OK timpani, forte, bitte, nicht fortissimo.” More directions. “Very, uh, militärisch, OK?” – he hums and stamps the rhythm. Fairbanks’s theme emerges, and orchestra is familiar with it by now, and they leap into it, body it forth. I can see the energy on stage.

Another run-through, this time in two. Sections pulling together, sounds knotting together – the result is a superb effort, tangibly effortful, athletic – it’s a joyful passage of performance. After the take, there is a buzz of accomplishment. Smiles, hums, instrumental scrapes and warbles. “Yes, eroica, let’s do that again please. Eroica, eroica. Sechs, acht. Douglas Fairbanks starts firing cannon at their main mast…”. […] There are more comments. “Clarinet… flute…”, Israel begins. But suddenly his alarm goes off. There is a chuckle, and a murmur. It is the signal for a break. Such is the tight timeframe for rehearsal that these breaks are as exact (and exacting) as a performance. There is thus an immediate dispersal of most players, but a few remain and fill the hall with incredibly rapid flights of sounds. Like birds have suddenly escaped their cage and fly about the room, singing. Last of all, a piccolo continues to flutter on her own. (Even as I write this down, Israel waves at me to follow. I grab my bag, dash from my seat and up onto the stage, and wend carefully through the low forest of music stands.)

[Later]

After another dash back to the stage, and over it, I find myself a seat in the middle of the auditorium. A dense hum of tuning masks my scramble for pen and paper. It begins anew. […] “We’ll do it a bit slowly as it’s very tricky.” The woodwind warble through an awkward passage, a dense thicket of sound. Then the whole orchestra goes together, and suddenly the hero occupies the soundscape – taking centre stage in the score. Soon, a sunbeam seems to spread through the music, a beautiful intimation of rightness – of justice. I glance at the empty screen, floating above the orchestra. Without the film projected, this score is a tone poem, conjuring images from sound. […] “Timpani, just for those two bars: hard hammers please. I wanted a kind of Beethoven scherzo sound.” They go through, but Israel calls out “Stop! Someone’s coming in early here. Please be very careful with counting…”.

[…] They move on. Israel flicks through his score. “OK. Dreitausendfünfundneunzig. This one’s more difficult for me than for you, as the timing with the film needs to be absolutely precise.” They go through, a little slowly. “Stop… A point of information…”. Here, Israel sings and gestures a sudden halt that must match the action on screen. […] The passage is tough. “I’m sorry, but this is the only way to do it. We have to match the film.” They persevere. When they get through it again, Israel complements their efforts. “After Sunday, you’ll feel like you’ve run a marathon.” Another take. High drama, difficulties. “OK, we’ll need to go through this. Bitte, just woodwinds and brass.” They do a run-through. At the end, Israel purrs, and the other sections tap their stands or stamp their feet in appreciation. “OK, strings, now it’s your turn…”. They go through, matching their colleagues in their own time.

“OK, let’s put this all together.” Israel crouches and sets up his laptop on a small stand beside the podium. He presses play with the tip of his baton, then turns to the orchestra. They play. […] “OK, please just follow me, I’ll need to go a little faster here, I’ll try to make it as clear as I can.” I keep an eye on the tiny monitor as Fairbanks cavorts in miniature. […] “I’m sorry but someone is getting ahead.” A tactful investigation is undertaken. First, the brass play their section to iron out the tempo. Then the woodwind play on their own. The error is found herein and easily fixed. Now all together, then once again – this time with the film. […] “Ja! We’re in time with the film now. Congratulations, it’s less tricky from here on. Not that this is easy, I know”, he adds. Indeed, it’s very hard work, and they press on.

[…] Directions of dynamics relayed from the podium, then through section leaders. The first violin relays it to her colleague three rows back. […] “Horn, yes, it’s a D-flat.” […] “Cymbal, I would ask you something here: it needs to be a real POW! It’s a specific effect for something on the screen.” They go again, and the percussionist – a young man at the very back of the stage, behind the level of the floating screen – gives it some welly. […] Israel explains the forte/piano to the strings as the moment when Fairbanks breaks the sword. “Justice is served!” They continue, until the horns squeak at a natural. Israel pauses, clarifies, just as the horns mock their own mistake in sound, then they all go again – and it’s perfect. It continues perfect until the woodwind go awry. Everyone chuckles tolerantly. “I guess we know what they think of my writing”, Israel jokes. “And don’t worry that here the bar numbers go all the way back to 0. It’s the same in everyone’s score, even my own. It’s just a printing error.” Another start, another false step. “Once more, please. We’re coming to the end of this thing, and it’s a lot of hard work.” Another run through, and it’s beautiful.

I watch the percussionist move across to the glockenspiel for his phrase, a droll intervention, placed before the sweetness of the lead violin solo. Then the great leap to “The End”, and it’s hugely satisfying. But “The End” must be reached again. Israel says how wonderful the basses sound. “People don’t realize how high the basses can go. It’s such a beautiful sound, so sweet.” […] They reach “The End” again, and a flutter of appreciative mutterings. “OK, we still have seven minutes. I don’t want to exhaust us, so achtundvierzig, bitte, and not to the end.” So they run through another passage, and then time runs out. There is a winding down, and Israel finishes with a few words. At this evening’s full run-through, Israel will be at stage level: the podium makes him too high for the audience. He promises to make his gestures as clear as possible, to keep them all together. “General rehearsal is for all of us, and if during the film I make a mistake or there’s a problem, I’ll just indicate to go to the next number. So don’t worry. It might happen; it might not.” […] A rapping of stands as orchestra salutes Israel. It is “The End” – for now.

Friday, 30 January 2026: Kongresshalle, Nuremberg

The night of the concert, I approached the hall from the front of house. The space that I had sat the day before was the same yet transformed. The darkness outside, the warmth inside, and the bustle of a crowd finding its way in – these factors made it more enticing. The seats filled out, and as the orchestra appeared – this time in formal black – the audience greeted them with warm applause. The players tuned up, and then Israel appeared from the back of the stage, clutching his score. After bowing, he took his place – without the raised podium. From my seat, a few rows from the front, his raised arms were just below the lowest part of the screen. I always enjoy this tension between the physical bodies of the performers and the projected bodies of those on screen, the way their two spaces are placed side-by-side, their two times placed in synchronicity. The lights fell, leaving the glow of lamps among the players, and the faint glow from small spotlights above the stage. (I break my continuity here to observe that these spotlights were turned off after the interval. I wonder who requested this? I’ve never been to a rehearsal of a film concert without seeing a protracted debate about lighting, where the respective concerns of musicians, projectionists, and venue managers are hotly contested.)

The introductory restoration credits were so numerous that they soon drew a few titters. Israel handled this moment perfectly. Turning to the audience with a smile, he said: “Don’t worry, we’re next!” It was a nice way to win us over (he got a good laugh) but also increased the drama of anticipation – for he had to be quick to turn around and make himself ready for the first cue. The last credit faded away; Israel raised his arms; the film’s first title card appeared, and the orchestra burst into life…

Seen at last on the big screen, The Black Pirate looked stunning. Since this MoMA restoration is not yet available on home media, I can’t offer visual samples. But even the single frame that I can find (from the MoMA page for this project) reveals the astonishing difference in image quality with the previous restoration. (See the images below, with the MoMA frame on the right.) Anyone used to the washed-out colours of old will be astounded (as I was in Nuremberg) at the richness and warmth of the new restoration. Suddenly, the tones of the wood on the ships, the fabric of clothing, the burnished skin tones, the deep blue-green waves, the golden sands – suddenly, all these inhabitants of the screen made sense. It was as if some magical elixir had given them back to their true selves, like they had reinhabited their former bodies. Damn, this film looks good!

The two-trip Technicolor palette is never showy, in the sense of throwing garish colours on screen. In fact, you might say it looks purposefully withheld. The dominant colours are rich, but muted. The film often resembles the canvases of seventeenth-century masters, especially the way the Princess is dressed and lit. Billie Dove might not have a character of great psychological depth to portray, but every shot of her looks fabulous. The way her velvet dress is captured by the colour, you can feel its fabric, sense the sheen of its soft material. And when she turns to one side, gripped with suppressed emotion, the light shapes her profile and haloes her hair – and suddenly it’s like a centuries-old painting come to life.

If the film’s palette is subtle, this also allows it to make certain moments stand out through colour. There is a superb scene early in the film, when the pirates are pillaging a merchant ship. When one of their prisoners hides a valuable ring in his mouth, the Pirate Leader (Anders Randolf) orders one of his men to retrieve it. He mimes a cutting gesture, so we know what’s coming. But we don’t see it. The camera stays put before the Leader as the other pirate gets out his knife, rolls up his sleeve, and stomps out of shot. The Leader stands, chews, spits. A few seconds later, the pirate reappears and gives the ring to the Leader. As he does so, we glimpse his bloody hand and bloodied knife. Seeing this moment on screen in Nuremberg, I nearly gasped at the sight of the blood: amid the browns and greens of the composition, the Technicolor blood is a slick shock of red, gleaming gruesomely on hand and knife. It’s the most vivid patch of red in the entire film, and so perfectly utilized. The murder is all the more shocking for taking place off-screen, its casual brutality brilliantly captured – felt – in that slick of red. (Later, there is another moment when the Pirate Lieutenant (Sam De Grasse) is comparing captured swords. To test the weight of one, he runs through its former owner – the moment of death again happening just off screen. The moment is chilling enough, but the grimly pleasing punchline is when the Lieutenant then wipes the blood from his blade on the victim’s trousers.)

As with its use of colour, the film reserves its camera movement for one or two special moments. Having remained virtually static throughout the film, there is a remarkable instance of movement in the climactic scene when the Pirate Lieutenant approaches the cabin in which the Princess is guarded by MacTavish (Donald Crisp). We know that he is about to claim his “right” to her body, and the one-armed MacTavish is her only protection. As the Lieutenant reaches the bottom of the small staircase, MacTavish comes forward – but the camera slowly retreats, and the Lieutenant firmly pushes the old man backwards. MacTavish retreats, too, then tries again to stop the Lieutenant. The camera pauses, only for the Lieutenant to push MacTavish back – and the camera withdraws before him once more. MacTavish makes one last effort to stop the Lieutenant, and the camera halts. But in a fraction of a second, the Lieutenant raises his pistol and clubs MacTavish to the floor. The Lieutenant looks ahead, past us, with dreadful calm. He walks on, the camera moving back before him. It’s such a striking scene, wonderfully played and directed.

Then there is the most astonishing shot in the film, when Fairbanks is carried from the depths of the ship to the top of the deck. The camera stays with him – centre frame, perfectly steady – as he rises, miraculously, joyfully, laughingly, via the arms of his men, through deck after deck, space after space. The way his arms reach up to catch hold of each new hand is so wonderful. It’s like he’s swimming upwards from the depths, just as his men earlier (equally miraculously) swam underwater towards the ship. It’s the triumphant, magical ascendency of our hero, our star – but also a kind of bodily metaphor for the narrative itself, with this final shedding of obstacles, of tension, almost of gravity, as rightness and justice are restored. It shows you how you might fly, but it’s a flight sustained by a whole team working together to make it so. It’s a perfect shot, but perfect in a way that takes you by surprise. Though we have seen plenty of stunts on screen, this last stunt is one performed by the film itself. Having reserved its movement for one or two brief moments beforehand, here the camera is miraculously unchained. God, what a shot this is – and what a star Fairbanks is.

And at every point in the film, Israel’s music knows just what to do. His score fits The Black Pirate like a glove. In the concert, all the hard work of the rehearsal makes sense – becomes fully realized. What had been a pleasingly abstract tone poem in the rehearsal was now a fully-fledged co-ordination of sound and image. The pleasure of this aesthetic marriage was not just in the deft movement between motifs for individual characters, for ideas, for actions, for situations, but in the individual moments that the music recognized and reacted to. Israel orchestrates specific visual cues for sound: gunshots, explosions, trumpets. One of the added pleasures of watching a rehearsal is the way you carry a tension with you into the concert hall or cinema. You have seen the musicians try (and sometimes fail) to time their sounds with those actions on screen. Once, twice, thrice they go through the cues – but now, in the hall, before hundreds of spectators, it suddenly counts. There’s no second chance, and there is a part of me that always worries on their behalf. (I suppose it’s my very English sense of embarrassment, waiting and dreading to be exercised.) But this evening, every single visual cue is carried off perfectly. It’s so, so satisfying to see a silent film live like this – because of this. The possibility of error makes live performance thrilling in a way the exact same music can never be on a recorded soundtrack. Here are real musicians, relying on their individual and collective skills to traverse an extraordinary obstacle course of co-ordination and timing. The endless action of The Black Pirate makes for a perfect, and perfectly challenging, marathon for performance – and for viewers, watching both film and performers.

It’s not just the continual progress of sound, it’s the sudden leaps and transitions that make it all so impressive. Israel’s command of the orchestra was marvellous. I loved watching the sideways swipe of his left arm at the end of a cue: it’s such an arresting gesture, controlled and dramatic. The concert answered the questions I had from rehearsal, for with the film in place these sudden gestures made sense. I had wondered about the cue from bar 2777, which was revealed in concert as the sequence for “The noonday of the tomorrow.” Here, the Pirate Lieutenant and the anxious crew watch the shadow of the sundial creep towards midday, when the “agreement” will expire – and the Princess is no longer to be kept “spotless and unharmed”. The score is heavy with tension, building to the moment when we see the shadow past the point of noon. Here, Israel’s dramatic sweeping gesture suddenly halts the orchestra. It as if, while they played, there was still some protection for the Princess. Now the film is briefly stripped of sound, and the awfulness of what the Lieutenant plans is laid bare. The music stilled, there is reaction on screen. The Lieutenant’s mouth curls into a wicked smile. He tosses aside his pewter mug, then throws out his arm to signal the crew to set sail. As if in answer to this gesture, the music resumes – spelling out Lieutenant’s three-note motif in heavy, sinister chords.

Here, then, was the answer to my question in rehearsal, the dramatic realization of Israel’s sweeping gesture. It is quite literally for show: to show the players what to do; but it’s entirely practical: the gesture is part of the mechanics of performance. Indeed, Israel’s movement on stage was part of the tension of watching The Black Pirate live. When the film cuts between Fairbanks coming to the rescue and the events on ship, the sudden switches between musical motifs are matched by the physical changes in Israel’s posture (the way his body tenses, his arms tracing new tempi, the downward swish of the baton), and by the collective reorienting of the musicians’ bodies (the strings swooping into a new phrase, the percussionist stepping across to another instrument, the glint of brass preparing for an entry).

And it’s superb music, equal to the images – respecting them, admiring them, trying (and succeeding) to do them justice. (Israel spoke of the pleasure of watching justice being served on screen. I think the same applies to the music: it’s a pleasure to hear justice being served by the score.) It’s an original score, but it sounds entirely in keeping with the period of the film’s production. Israel also cites a couple of pieces from the period of the film’s setting (c.1700). There is a (bawdy) sea shanty as the pirates have their feast, and there is a delicious baroque piece that accompanies the minor nobility who are captured. The latter piece, in particular, is perfectly utilized. This music has a wonderfully old-fashioned, dignified air to it – perfect for the way these characters are dressed (in conspicuous velvet and lace) and the way they behave (their refined bearing, their gentile gestures). Just as these nobles are surrounded by rumbunctious pirates, so their music is a little oasis, surrounded by the boisterous swagger of the score. (And surely just as liable to be overpowered.) The contrast is not overemphasized, but the flourishes of this period music are a sudden relief – a sense of somewhere, and somewhen, else.

So too with the music for the Princess, the most conspicuously well-dressed figure in the film – and also the most vulnerable. Her theme, often highlighted by solo violin, is another oasis of mood and feeling – delicate, light, beautiful – in the midst of the score. Yet it also stands as a kind of musical defiance against the dangerous, brooding theme of the Pirate Lieutenant (so perfectly played by De Grasse). And when, near the end, the rescue party appears on the sea, the delicate love theme associated with the Princess is suddenly reinforced by the full orchestra just as the film cuts to the “Black Pirate” standing at the head of the boat. The reappearance of this theme makes it clear why he is coming back, but it’s also a kind of union – or promise of union – between him and the Princess. Reorchestrated, the music is the same yet transformed. Not just her theme, it is now their theme.

What was brought home to me in the concert, again and again, is how well Israel’s score understands the film. It finds the right rhythm, the right mood, and knows how and when to change gear and register. Aside from anything else, it’s also great fun. The music acknowledges – and articulates – the sheer pleasure of watching Fairbanks on screen. His musical theme – bold and bright – is as winning as his visual appearance. Few stars can make you smile just by the way they walk, by the way they hold themselves, by the way they smile, or withhold a smile. Fairbanks might impress with his extraordinary stunts (slicing through sails while falling, leaping up chains, clambering rigging), but he can also communicate with the simplest and clearest of gestures. I love his pose on the island at the start of the film, where he spells out grief and isolation with the way he sits alone on the sand, head bowed between his legs. Fairbanks’s character has just buried his father, and his pose here is like that of a lonely child, the contrast between the vulnerable posture and the athletic bulk of his body beautifully touching. Later, there is another moment where a simple gesture says so much. When he forces the “Black Pirate” to walk the plank, the Lieutenant tells him that “at the bottom of the sea you’ll find the ransom ship”. Fairbanks twists his head a little to one side, so we see him in profile: and we know that his character realizes that he has been betrayed. Though he is blindfolded and is seen only in long shot, this little beat in Fairbanks’s performance sends us a signal we can understand.

All these moments make the climactic scenes so pleasing to watch, when Fairbanks and his rescue party arrive and overpower the pirates. The wonderful unfolding of these final minutes, with Fairbanks’s seemingly infinite supply of men who can swim and leap and overcome with their collective bodies all obstacles, is accompanied by a bustling torrent of sound, the strings restlessly muscling their way forward, wave after wave, like the figures on screen. When “The End” was reached, and the orchestra wound up to its sign off, there was a great cheer of enthusiasm in the hall, and a rousing ovation, peppered with bravos. After taking the applause, Israel motioned that he wanted to say a few words. In German, he praised this hundred-year-old film for its technical achievements – but also for speaking about the necessity of justice, and the triumph of good over evil. Apologizing that his German was failing him, he continued in English to say how touched he was seeing the local schoolchildren attend the rehearsal: he hoped that they offered us a bright future. He also paid tributed to the Nürnberger Symphoniker, praising their hard work and skill. “You have a wonderful orchestra”, he finished. “Treasure it. Support it. Thank you – now go have a beer!” With a final round of applause, the evening ended.

In summary, this was an excellent way to start my filmgoing for the year! I fervently hope that the MoMA restoration of The Black Pirate is released on Blu-ray. But nothing can beat seeing this film live with orchestra. In Nuremberg, I had an absolutely wonderful time in the company of Fairbanks’s images and Israel’s music. Bravo to all involved!

Paul Cuff

My great thanks to Robert Israel and to the Nürnberger Symphoniker for allowing me to attend rehearsal.