This piece is devoted to the score arranged and orchestrated by Bernd Thewes for the 2016 restoration of Pabst’s Die Liebe der Jeanne Ney (1927). I confess at the outset that I love this score unreservedly. I have relistened to it all the way through a dozen times, and to certain sections of it many times more. No review that I’ve read has gone into much detail about the music, which seems to me a great oversight. This piece tries to make amends for that.

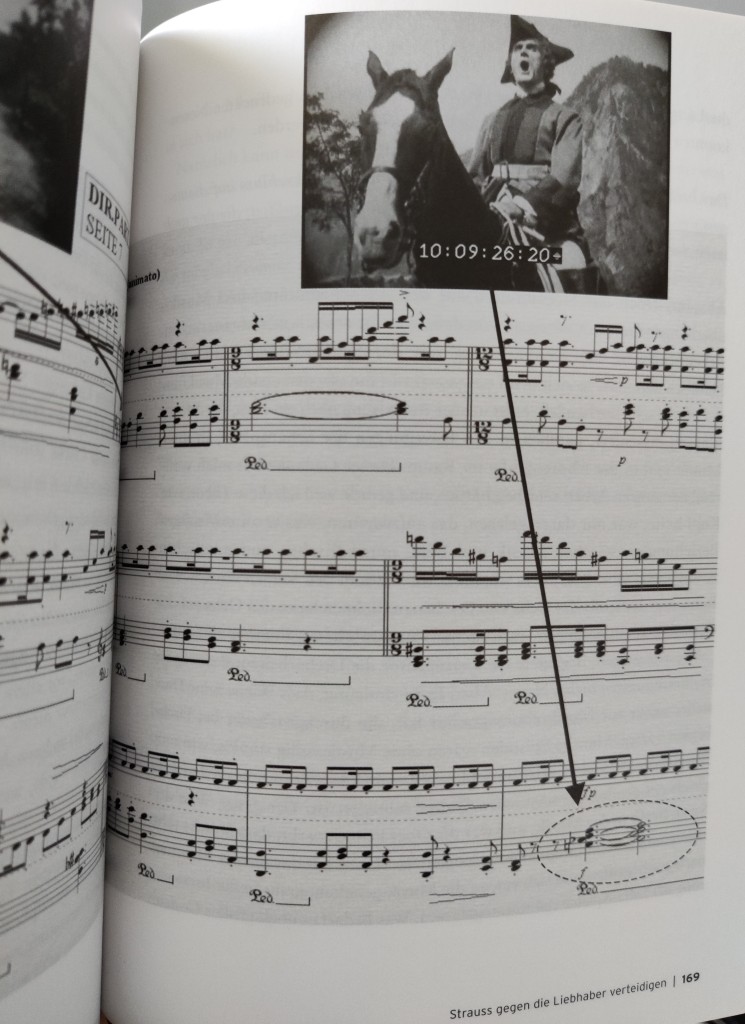

The model for Thewes’s 2016 orchestral score is a piano score from the music collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. This anonymous work is not an original composition, but a compilation of existing music. It was likely made in the 1930s when Iris Barry (MoMA’s curator) acquired a copy of Die Liebe der Jeanne Ney from the Reichsfilmarchiv in Berlin. We don’t know the identity of the musician who assembled this piano score, nor does the score identify the pieces of music used within it. While there is recognizable material from familiar composers (Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninov, Verdi), much of the music remains obscure—at least to me.

What’s so pleasing about Thewes’s arrangement is that it treats the identifiable and unidentifiable pieces with equal originality. Thewes began work by dubbing the piano music to match the video of the restored film, then orchestrated the score from scratch to produce a coherent sound world that fitted the images. There is a tremendous sense of freedom in this method: the familiar and the unfamiliar are made to sound equally new. Thewes’s choice of instrumentation is key to this sense of playful recreation. To the forces of a symphony orchestra (including piano) are added electric bass, saxophone, Hammond organ, and drum set. Much like the contents of the original piano score, these forces are a blend of the classical and the popular.

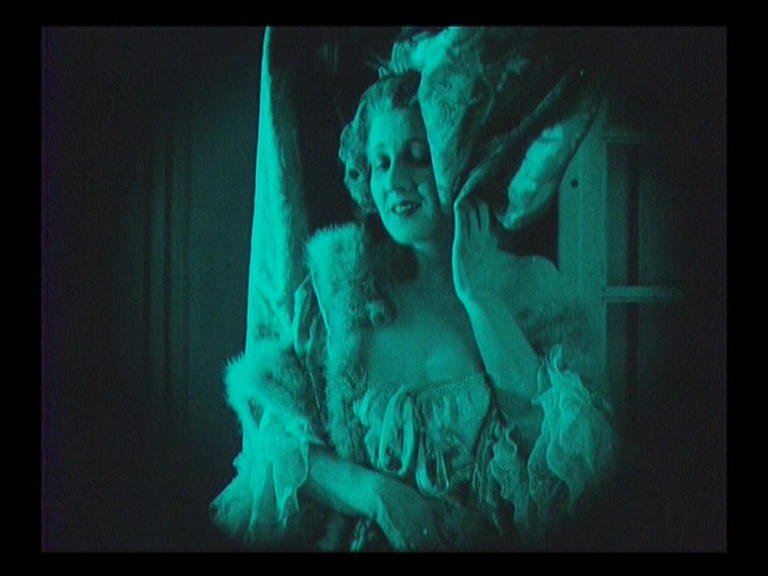

One of the pleasures of listening to scores based on musical compilations is recognizing familiar pieces, and hearing how they are (re)arranged to suit the film. Two of the main themes in the film are well-known pieces by well-known composers. The piece associated with the romance between Jeanne (Édith Jéhanne) and Andreas (Uno Henning) is “June”, from Tchaikovsky’s piano suite The Seasons (op. 37a, 1875-76). In Thewes’s score, this piece—a barcarolle—becomes a warm, mellow, melancholy theme taken up by the strings and supported by the Hammond organ. The organ might suggest a matrimonial—if not religious—tone to such a piece; no doubt it does in this score, but I think the distinctive timbre of the Hammond also offers something else. Its use in prog rock and pop music brings in a very different context than a pipe organ would from the context of theatre or church. (When, in later scenes, it is used in combination with an electric base, the Hammond also brings in the context of horror films.) One might say the Hammond organ is a secular counterpart to traditional pipe organs. Its use in the orchestration of Tchaikovsky’s “June” might hint at religious matrimony but it does so only within the context of secular music: a classical melody rendered on a popular instrument. Its timbre also (to my ears) heightens the sense of melancholy. We first hear the piece when Jeanne is staring into the dark, remembering time spent with the absent Andreas; this music is not just an expression of love, but of love lost or love yet to be fulfilled.

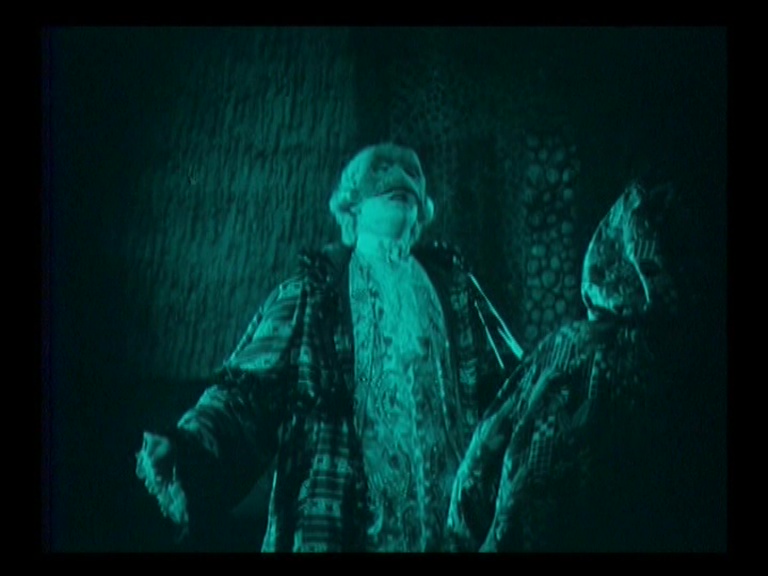

Another recurring theme is the music used for the villain of the film, Khalibiev (played by the deliciously repellent Fritz Rasp). For this, the score uses Rachmaninov’s Prelude no. 5 in G minor (from the op. 23 preludes, 1901-03). The orchestration emphasizes the sinister, irregular gait of the music: with the equivalent of the lowest (lefthand) notes from the piano taken by the bassoon and soon strengthened with brass. Later, Thewes allows the piano to join the orchestra, turning the prelude into a kind of concerto. If the “June” motif is an unpretentious, accessible theme for the lovers, the more flamboyant (more overtly “classical”) Rachmaninov prelude reflects the sinister pretensions of Khalibiev, who poses as a kind of exiled Russian aristocrat.

Other familiar pieces in the score are more radically reworked. “The Internationale” anthem (music composed in 1888) is cited several times. This well-worn tune takes on a new dimension thanks to the way Thewes uses Hammond organ, drums, and brass in his score: there’s suddenly a narrative drive to the music, one that makes it more than a recitation of the anthem’s own themes. The melody becomes threatening (for the battle scenes), boisterous (for the Bolshevik courtroom), and celebratory (for the flashback to Jeanne’s first sight of Andreas). The variations in tempo and orchestration transform what can be a slow, turgid piece (designed for the accompaniment of text, after all, not images) into exciting, thrilling music that sounds fresh and alive.

More subtly, in the scene where Andreas is in a bar, plotting with his comrades, the score uses Tchaikovsky’s “Danse russe”, from 12 Morceaux for piano (op. 40, 1878). But the way the tempo is altered (shifting in line with the ebb and flow of conversation and movement on screen) makes the music entirely serve the film. Likewise, immediately after the above scene, excerpts from Tchaikovsky’s Marche slave (op. 31, 1876) are rearranged to fit the rhythm and content of the images. Its first appearance (for the first shot of the Bolshevik forces gathering for the assault) is only a few bars from the sinister opening of the piece, but Thewes adds cymbals to subtly mimic the splash of horses galloping through the water on screen—and the added rhythm quickens the propulsion of the “march”. A few scenes later, the Marche slave’s next appearance is much in line with the original orchestration (from its finale), but after a couple of bars the organ enters to take up the rhythm: with a few deft touches, a very familiar (and much used) piece of music becomes part of the specific sound world of this score.

Later in the film comes a piece of music whose transformation particularly struck me when first I heard it. When the newspapers announce the murder of Raymond Ney, the score uses the main theme from Verdi’s overture to La forza del destino (1862/69). It’s a very well-known piece, but in Thewes’s arrangement it took me totally by surprise. For the theme is first spelled out by the organ, supported by drums and brass before the strings enter. After this first iteration (and a fabulous diminuendo that ends in the lowest growlings of the brass), the theme is given over entirely to the organ. It’s the perfect example of making the familiar sound new. There’s more than a hint of prog about this melding of classical repertory with modern instruments (the drum kit and Hammond organ are exemplary of a prog soundscape). It makes the piece doubly new: recontextualizing it to the images of 1927 and to the worlds of both classical and popular music. And, quite simply, it’s fun.

Indeed, I should keep saying just how fun Thewes’s orchestration is throughout. To pick another moment, listen to how we are introduced to the detective agency of Raymond Ney (Adolf E. Licho) in Paris. The score uses Armas Järnefelt’s Præludium (1899-1900), a piece not now familiar for most. (After a lot of digging around trying to identify this piece, I realized that not only had I heard it before but that I actually owned it on CD. I suspect I am among a very small number of people who own a collection of Järnefelt’s work on CD, and an even smaller subset who own more than just the recent release of his music for Stiller’s Sången om den eldröda blomman (1919).) Bearing in mind that Thewes orchestrated this piece from its piano reduction, it’s remarkable how this 2016 arrangement is both similar to and distinct from the original. Thewes’s orchestration makes this charming fanfare sound more baroque than the original (with more emphasis on the bright, shiny timbre of brass). But with the addition of the saxophone, it also melds its tone into the sound world of the rest of the film. Listening to them side-by-side, I find I prefer Thewes’s orchestration to Järnefelt’s own arrangement. (Thewes removes the unnecessary pomp of Järnefelt’s cymbals and glockenspiel for the forte passages.) And the timing of the piece for the action on screen—the growling brass for Gaston’s demand for “Geld! Geld!” , the solo violin for the client’s tearful farewell to both his adulterous wife and his money—is marvellous.

But there is one section of the film that I have listened to even more times, which is when Andreas first arrives in Paris and reunites with Jeanne. This run of scenes—less than ten minutes of screen time—uses pieces of music that I have been unable to identify. Part of their charm for me is exactly this sense of the unknown, and the revelation of how beautifully arranged and orchestrated they are for the film.

The first scene in this section is of Poitra (Hans Jaray) waiting for Andreas outside the train station. The strings spell out the main melody: a simple, sweet, slow sigh. The two men great each other and, as soon as Andreas steps into the taxi, the organ takes up the main theme from the strings. When the car drives away from the station, the drums mark out the underlying beat—as though catching on to the tempo of the traffic. The camera tracks back before the car, and slowly the sense of location becomes the subject of the sequence. For here is the Gare du Nord, filling the width and height of the screen, and traffic filling the foreground. People crisscross the street. The taxi must switch lanes, weave back into view. I find it hard to say what it is about this scene that I find so moving, but I know that the music brings something out of it that is both touching and melancholy. The slow, sweet, sad melody is light music as its most winsomely romantic. I have no idea what piece it is, or who wrote it: but it bears the hallmarks of a popular tune, since it is instantly graspable, hummable, whistleable. It’s a curiously moving experience, too, to find this anonymous melody popping back into one’s head many weeks later (as it did and does into mine), and to be able to rediscover its melodic contours so easily.

The way Thewes’s arrangement handles the tune is also key to its effectiveness. I’m not normally a fan of organ scores for silent films, but I love the use of any keyboard instruments as part of an orchestral texture. For this scene, the texture of the melody is carried by the Hammond organ and—just for the last repetition of the tune—supported by a sweep of undivided strings. Its simplicity as a tune is made doubly effective by the simplicity of its rendering here: all the instruments unite for the final bars, producing a splendid sheen of sound. The presence of the Hammond organ in the midst of this piece gives the music (to my ears) a pleasingly vintage aura, summoning up a past with its warm tones. When I was a child, our neighbour (born, I think, around 1918) had a small Hammond organ at the entrance to his living room. On this, he would accompany himself singing sentimental songs from his youth of the 1930s and 40s. The Hammond organ in Thewes’ score for the melody in this Gare du Nord scene sets me in mind of this kind of popular mode: it is easy on the ear, memorable, sweet, warm. The organ was a widespread instrument in cinemas of the 1920s, and continued to be one of the few surviving aspects of live music in theatres after the arrival of sound. The instrument is thus associated with several generations of cinema sound, and its use here for this piece of (once) popular music is perfectly judged. It’s sentimental in the right way, and makes the texture of the melody more interesting than if scored simply for the sweeping strings. Purely and simply, it’s lovely. And it functions also to underline one of the pleasures of the film: seeing Paris. The sense of nostalgia in the melody also works in relation to the streets we see on screen: we are driving slowly through the past, observing the motions of the people on the street, the slow passage of the cars and trucks. The melody moves as slowly as the taxis, as the camera itself, as it tracks back through the street. It’s perfect.

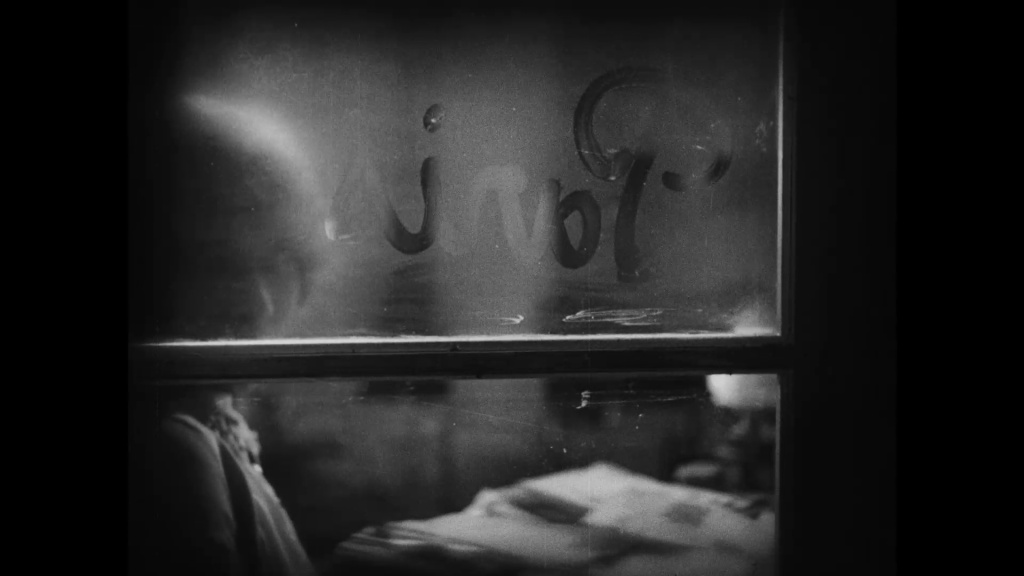

For the brief scene of Jeanne at her typewriter, dreamily typing Andreas’s name before XXXX-ing it out, we hear a repeat of the melody used earlier in the film that accompanied the lovers’ last embrace in Russia. It’s like the melody is her counterpart to the dreaminess of the tune that greets Andreas at the station. And, like the previous melody, Thewes orchestrates this piece so that it’s a delightfully simplified sweep of sound—the organ this time rounding out the last iteration of the theme (as if repaying the compliment from the previous scene, where the orchestra took over from it at the end).

Next, we cut to Khalibiev and Raymond Ney. Khalibiev is holding a bouquet of flowers, and now Gabrielle (Brigitte Helm) appears. In the score, a delicious combination of piano, harp, and strings sound out a skipping, nervous, innocent melody as she approaches. It’s perfect for Gabrielle, whose naïve trustfulness of Khalibiev almost unnerves the latter. Pabst provides us with an amazing close-up of Gabrielle, staring wide-eyed into the camera. We share Khalibiev’s perspective, gazing at this beautiful face with its gleaming eyes. (Hear how the strings end their phrase with a lovely diminuendo, climbing higher before fading away.) “I’m so happy!” says Gabrielle to Jeanne, and the music has been telling us this already. But beware Khalibiev! The presence of the piano in the orchestration here reminds us of Khalibiev’s own theme, and the way this instrument tends to rumble out from the brass and take it over. And Jeanne’s worried glance at Khalibiev coincides with another melting-away of the main theme in the strings: even when the melodic line is cheerful, the placement of each phrase can carry such subtle shifts in emphasis.

Outside, Poitra is waiting with the car. (Observe here how a cat walks into frame and sits, with perfect timing and placement in the corner of the frame, just before the handheld camera pans left to see the two women emerge from Ney’s building. It’s one of those lovely unplanned moments that comes from filming on location.) The main theme—a four note phrase, with an emphasis, like an excited skip, on the second note—is taken up by the strings. Pabst cuts to a long shot of the whole street. You can see the long flight of steps behind the alley, and the sun throws swathes of light and dark between the buildings. It’s a lovely image, with depth of focus and composition: here again Paris becomes the subject of the scene.

The women get into the back of the cab, which has its roof down to let in the sun. Poitra has with him a little posy of flowers, which he looks at, then throws over his shoulder to Jeanne in the back. The music is so perfectly timed here, swelling in volume in time with Poitra’s gesture. (Again, the melodic content is a simple repetition of material, but the tempo allows the beginning and ending of phrases to make an impact.) The cab sets off and the saxophone takes up the main melody. To me, the saxophone feels delightfully in keeping with both the easy melody and the sense of time and place on screen (and, thus, the emotions of the characters who inhabit it). Pabst’s camera sits facing the two women, each holding their flowers, Gabrielle clutching at Jeanne with her free hand. In the background, the shaded walls and sunlit road flash by. “Are we flying?” asks the enraptured Gabrielle. “Yes, we’re flying—into bliss!”

Listen to the joyful way the music transitions here: brass and drums take over the impetus of the melody, then beat out a faster rhythm. It’s as if the orchestra has warmed up, has broken into a run or a dance. For a few seconds, it’s just the brass and drums, rumbling around in a repeated refrain. It’s like the bumpy road that shakes them around in the cab. It’s the quickened heartbeat of the separated lovers. It’s the excitement of an anticipated meeting. And it’s the premonition of the bustle of the underground club that now appears on screen: for we see Khalibiev descend into the bar where he meets Margot (Hertha von Walther).

Pabst creates a marvellous sense of space here: behind the bar is a huge mirror, reflecting the spiral staircase from above, down which Khalibiev speeds. The orchestra switches to a swinging, brassy, almost tipsy melody. It’s the change in tempo and rhythm, as much as the textural one, that makes the contrast between this scene and that last so effective. The transition between one “cue” and the next itself becomes a chance to switch the orchestration, to emphasize a different texture and mood. Without the score in front of me (and not recognizing the music being used), it’s difficult to know precisely how the original score changes here. Listening to it multiple times, I almost feel that the music for Khalibiev is a kind of parodic distortion of the melody used for Jeanne in the cab. Certainly, it feels as though the first melody—sweet and sentimental—slowly morphs into its boisterous, unbuttoned sequel. The way Thewes orchestrates this shift makes it a perfect match for the images.

In the bar (to a foursquare, oom-pah-oom-pah, beat in the brass), Khalibiev flirts with Margot, orders two liqueurs, and downs his in one. Khalibiev stares at Margot. Pabst gives us a huge close-up of her face, her dark brows and eyes a kind of counterpart to the pale, luminous face and eyes of Gabrielle in the earlier scene. Having been bewildered by Gabrielle, able only to ghost a kiss on her forehead, Khalibiev now grabs Margot and plants a kiss on her brow—then marches back up the stairs, just as the rumbunctious brass rounds off its melody with a flourish.

Andreas is waiting on a bridge by an entrance to the park. (The place we see them visit is the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont.) He turns round, waiting anxiously for Jeanne. The organ, too, sounds out an anxious, excited tremolo. (It’s a kind of acoustic equivalent of an impatient tapping of the foot.) As Pabst cuts to a long shot of the road curving round towards Andreas’ position, the organ begins the melody that defines this next sequence: a quick, delightful, tripping tune that expresses the excitement of the lovers’ reunion. It is swiftly joined by the drums (at first very softly, then with a rattling of a tambourine), these added textures bringing out the sense of giddy fun in the music. For Andreas is leaping at the sight of Jeanne’s car, waving his arms and running towards her—and Pabst begins cutting between parallel tracking shots that follow the lovers. The strings join in, filling in the harmony, strengthening the melody. The organ skips along with the rhythm, while the drums spell out an excited beat underneath—brass occasionally rounding-out the theme. I love, simply love, the mix of texture of timbre that this combination produces: the fizz of the drum set, the deep warble and light chirping of the organ, the sweet richness of the strings. It’s almost silly it’s so delightful. And the scene itself is likewise sillily winsome as the characters rush madly toward one another.

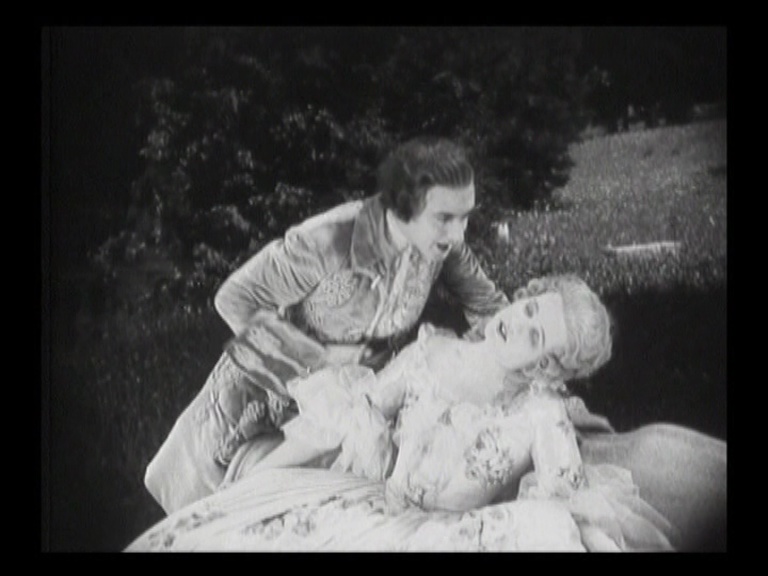

But for their actual meeting, everything slows down, stops. The melody of their courtship—Tchaikovsky’s “June”—floats in on woodwind, supported by wistful strings. And despite their energy, the lovers don’t end their respective journeys with a climactic embrace. Instead, Andreas doffs his cap, and they walk side by side, slowly, into the gardens. It’s strangely innocent, as though neither is quite ready to express their desires. The music waylays our expectations, reminds us of the lovers’ troubled past and uncertain future.

After cutting back to the car, to glimpse Poitra alone with Gabrielle, Pabst’s camera finds the lovers atop an artificial grotto in the park. It’s glorious to see across the rooftops of Paris: you can even match the same image to that of today’s skyline (which, thanks to the city’s ban on tall buildings in its centre, remains much the same as it was in 1927). The image of Jeanne and Andreas makes literal the sense of their elated state in each other’s company. They are (quite literally) on high. But it also carries an implied danger of their fall, of their togetherness being precarious. The music here repeats the same material heard in earlier scenes with the lovers (their last embrace in Russia; Jeanne’s daydream at her typewriter). Again, it is dominated by the tone of the saxophone, which floats over the strings. The orchestration is easy on the ear, but the use of the saxophone gives it a feeling not just of light music but of period light music. It’s a nod to the film’s setting and belonging to the 1920s.

Finally, I must finish with a comment on the last scenes in the film, set on a train as Jeanne wrests the incriminating evidence from Khalibiev. By way of prelude, I should note that the eponymous novel (by Ilya Ehrenburg) on which the film is based has the characters zipping about all over Europe on trains. Even if the film eliminates some of this journeying back and forth, there is more than one scene on a train and Thewes’s orchestration contains distinctive elements for these scenes. He includes percussive instruments, but ones that evoke something more than the simple sounds of coaches rumbling over tracks. Before Andreas is arrested, he is alone in a train carriage. He has just spent the night and morning with Jeanne and their new life beckons. In eighteen seconds of screen time, the score makes us sense everything around and within him. The melody is bright and peppy (it’s another piece I don’t recognize), made brighter and peppier by the addition of drums, bell, and triangle to the orchestra. The quick rhythm of the drums and triangle suggests not just the motion of the train but a kind of inner rhythm of the character: you can sense his joy as he sits, almost fidgety with energy, on the seat and smiles. And the fact that the view through the train window is of dappled trees, the light spilling across Andreas’s beaming face, likewise gives a visual sense of brightness and joy; the same sense of brightness and joy given to the music by the rhythm of drums and the sparks of the triangle.

The regular sounding of the bell harks back to the lovers’ morning, spent walking through Paris and at one point entering a church where they—all too briefly—link hands before the altar. It’s not a wedding, but the promise of a union together. Thewes included the bell in the musical climax for this earlier scene, and now it appears in this scene on the train as a reminder: it’s as if Andreas is summoning the sound of bells in his head, and we can hear it.

All this feeds into the final scene of Jeanne and Khalibiev on the train. Just as Jeanne tries to convince Khalibiev to help her, the two locals in their compartment proffer them sausages and bread. It’s a delightfully farcical way to increase the tension. And the score enters into the farcical spirit. The melody used at this point is a chirrupy, almost childish little theme. Thewes lets the woodwind carry this theme, with the rhythm backed up by the drums. The addition of the bell as a regular chime in this scene, as well as making the simple melody more musically interesting, has an ironic function in that it reminds us of the bell’s presence in earlier scenes: the wedding-like vision in the Paris church, Andreas’s private joy in the train carriage. There’s also a sense of a chiming clock, as if to remind us (musically) of impending deadlines: Jeanne must get the information from Khalibiev before it’s too late. Thus, this amusingly rustic tune functions to underline both the comedy of the scene and the dramatic tension underlying it. Like the scene itself, the music is a kind of elaboration of a simple theme, its function to produce tension by slowing things down at the moment when we want things to hurry up. It’s like the two locals come are humming their own tune, heedless of the drama they suspend by their presence.

After the climax, in which Jeanne wrestles with Khalibiev and finds the missing jewel, there is an extended hiatus before we reach the “end”. The film fades to black, but the black screen continues for another forty seconds until the title “ENDE” appears. Why? (This is not, as far as I am aware, a restorative choice, but the original ending as chosen in 1927.) It’s as if the blank space here—temporal, aesthetic—is a kind of inner space for Jeanne to savour her joy. So we sit in the dark, her blissful smile the last image in our mind’s eye, and the orchestra keeps playing; that it does so shows respect, sympathy even, for the black screen. This hiatus is also a chance for the music to wind down, to relax after the tension of the last scene. The music here derives from the same piece used for the earlier scene at the church, so it’s as if the score is reliving the past—and envisioning the future of the lovers. It makes the ending more complex, somehow, more resonant. And, from my point of view, it nicely refocuses our attention back on the score itself. It deserves to have the last say.

Die Liebe der Jeanne Ney is a film I had seen many years ago but never appreciated. Perhaps one reason is the quality of its earlier incarnation on DVD. That version, released in 2001 by Kino, featured a score by Timothy Brock. Revisiting this now, I am reminded how oddly subdued it feels compared to the film—and most especially to the 2016 score. It’s not just the tone of the music but the quality of the performance and recording. Produced for an earlier release (presumably VHS or even laserdisc) in 1992, the Brock score is performed by the Olympia Chamber Orchestra. This group also recorded other Brock scores for Murnau’s Faust (1926) and Sunrise (1927) in the early 1990s. I love Brock’s score for Faust, but the recording for the soundtrack doesn’t do it justice. The Olympia Chamber Orchestra is an irregular ensemble rather than a professional orchestra. Their performance is perfectly adequate, but I can imagine a far sharper, more convincing rendering. (Frankly, the playing—especially the strings—is sometimes a bit ragged. Too often the ensemble sounds out of sync, if not actually out of tune, and the dull recording hardly helps.)

The production values for the new restoration of Die Liebe der Jeanne Ney belong to a different league altogether. Recorded in February 2017 at the Westdeutscher Rundfunk, with Frank Strobel conducting the WDR Funkhausorchester Köln, the soundtrack for the Blu-ray is superb. Both the orchestral performance and the sound recording are exemplary. (I should namecheck the sound engineers listed in the credits: Rolf Lingenberg and Walter Platte.) This is the kind of result you can get when proper resources are fed into a film restoration.

My deepest thanks go to Bernd Thewes for answering my questions on his work on this score. This piece can only be a small expression of how much joy his music has brought me.

Paul Cuff