In the summer of 1926, Cecil B. DeMille embarked on what was considered to be an enormously risky project: an epic treatment of the life of Jesus Christ. There had been plenty of Christs seen on screen in early cinema. In France, films about the Passion produced some of the longest productions thus far assembled. Pathé’s La Vie et la passion de Jésus Christ (Lucien Nonguet/Ferdinand Zecca, 1903) was nearly 45 minutes, while Gaumont’s La Vie du Christ (Alice Guy, 1906) was over 30 minutes. These early Christian narrative films were also boasted elaborate forms of cinematic spectacle. When Pathé remade their La Vie et la Passion in 1907, Segundo de Chomón took charge of the elaborate stencil- and hand-colouring of Zecca’s film for exhibition. Thus, long-form narrative and colour effects were always part of the history of silent biblical productions. But the context for DeMille’s film—to be made on the largest possible scale, complete with Technicolor sequences—was rather different. In the US in the 1920s, there had been much controversy about the depiction of Christ on screen. Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ (1925) had famously been obliged to include Christ only in the form of an occasional limb or edge-of-frame glow. Were censors, critics, and audiences ready for a modern dramatic interpretation of the Passion? And was DeMille the man to handle the project?

It turned out that he was, and that they were. For a start, DeMille tried to inoculate his production against religious concerns about Hollywood by having Mass performed every morning on set, as well as offering daily prayers via various religious leaders. He also imposed a “morality clause” in the contract of Dorothy Cummings, who played Jesus’s mother. And H.B. Warner, who played Jesus, was segregated from the rest of the cast to preserve his aura of otherness—and presumably to stop him socializing in ways that would not be becoming for someone playing his role. DeMille’s screenplay—by Jeanie MacPherson—was also built around incidents relayed in the New Testament, and the film’s intertitles are dominated by biblical citation. In sum, DeMille did everything in his power to make sure his production would offer a sincere and sanctioned depiction of its subject—and (as ever) his publicity department made sure that people knew about it.

When the film was released in April 1927, The King of Kings still caused a degree of controversy: depictions of Christ were (and, of course, still are) a sensitive issue for many spectators. But though the film encountered censorship in various territories, it was a resounding critical and commercial success. An early review in The Film Daily (20 April 1927) took the lead in what was to be an avalanche of glowing reviews:

There can be said nothing but praise for the reverence and appreciation with which the beautiful story here has been developed. DeMille has been successful in striking a tempo that is remarkable for the peaceful and benign influence it wields on the spectator. […] The spiritual fibre of innumerable numbers throughout the world are being stirred to their very core. […] [DeMille] has shown a supreme courage and a vast daring. He has been brave enough to show The Christ on the screen. […] The King of Kings is tremendous from every standpoint. It is the finest piece of screen craftsmanship ever turned out by DeMille.

Writing in Photoplay (June 1927), Frederick James Smith followed suit:

Here is Cecil B. DeMille’s finest motion picture effort. He has taken the most difficult and exalted theme in the world’s history—the story of Jesus Christ—and transcribed it intelligently and ably to the screen. / De Mille has had a variegated career. He has wandered, with an eye to the box office, up bypaths into ladies’ boudoirs and baths, he has been accused of garishness, bad taste and a hundred and one other faults, he frequently has been false and artificial. One of his first efforts, The Whispering Chorus [1918], stood until this as his best work. / The King of Kings, however, reveals a shrewd, discerning and skilful technician, a director with a fine sense of drama, and, indeed, a man with an understanding of the spiritual. / The King of Kings is the best telling of the Christ story the screen has ever revealed. […] You are going to be amazed at the complete sincerity of DeMille’s direction. Nothing is studied. There is no aiming at theatrical appeal. DeMille has followed the New Testament literally and with fidelity. He has taken no liberties. […] The King of Kings is a tremendous motion picture, one that, through its sincerity, is going to win thousands of new picture goers. DeMille deserves unstinted praise. He ventured where few would dare to venture, he threw a vast fortune into the balance and he carried through without deviating. Congratulations, Mr. DeMille.

And in Picture Play (August 1927), Norbert Lusk saw the film not just as a triumph for DeMille but for cinema itself:

The King of Kings is Cecil B. DeMille’s masterpiece, and is among the greatest of all pictures. It is a sincere and reverent visualization of the last three years in the life of Christ, produced on a scale of tasteful magnificence, finely acted by the scores in it, and possessed of moments of poignant beauty and unapproachable drama. This is a picture that will never become outmoded. […] Until you see The King of Kings you will not have seen all that the screen is capable of today.

I begin my piece with this context because I feel that what follows would otherwise do an injustice to DeMille’s film. Following the historical high praise, my own reaction will seem distinctly—perhaps unfairly—negative. Over the recent Easter weekend, I was looking for something culturally appropriate to watch. (I’m in no way religious, but sometimes it’s nice to feel “seasonal”.) I chose The King of Kings because I’d had the gorgeous French Blu-ray edition produced by Lobster say on my shelf for a long time—unopened. I don’t think I’d actually seen the film all the way through before, and frankly I couldn’t make it all the way through in one go this time. Rarely have I been so intellectually bored when watching a film of my own free choice.

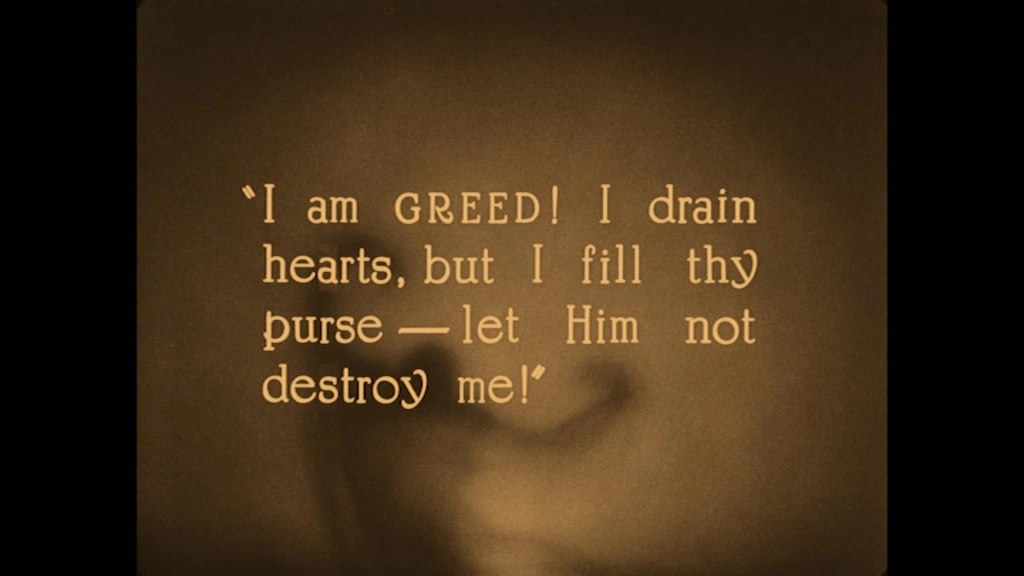

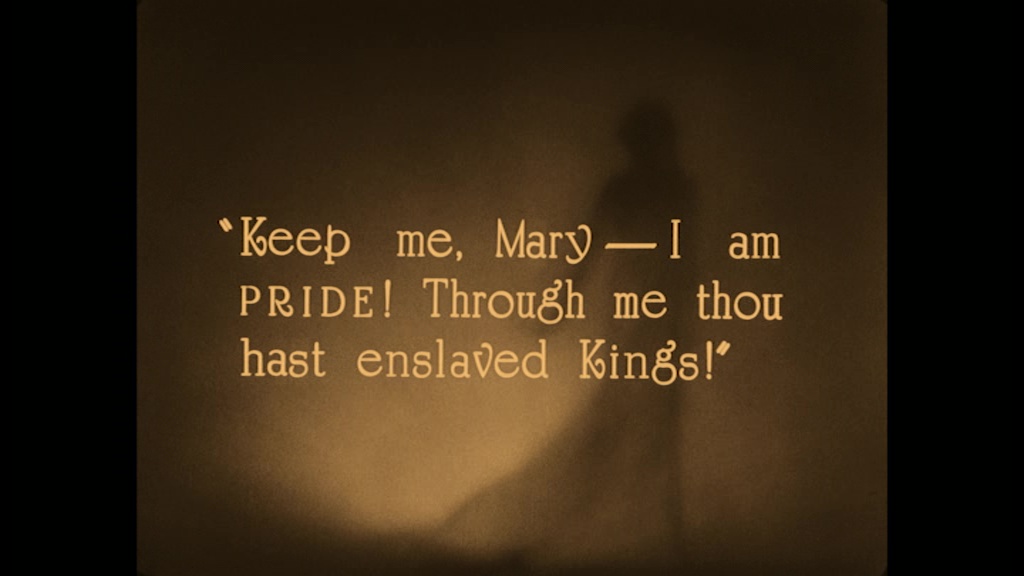

It started so promisingly. A two-strip Technicolor cabal of harlots and decadents, lounging around in lurid pink robes. High drama, high kitsch. Mary Magdalene is Judas’s former lover and wants to know where he is. Discovering that Judas is in league with a carpenter named Jesus, Mary starts issuing instructions to her servants: “Bring me my richest perfumes! […] Harness my zebras!” (I think “Harness my zebras” is the most fabulous intertitle I’ve seen for quite some time.) So off she rides in her zebra-pulled carriage to find Jesus and Judas…

Thus ended my dramatic involvement with the film. From this point on, I was increasingly restless. I can only presume that DeMille started his epic with this sequence precisely to lure in a wider audience. Want debauchery, colour, spectacle? Here it is! Now we have your attention, we segue to the real story… Alas, Demille’s Te Deum for God was tedium for me. By the halfway point, I was experiencing such crippling mental boredom that I had to stop. I wanted to rant and rage, or run madly into the night, to vent my frustration. After a break (and a more sedate session to finish the film), I have been trying to ponder why my reaction was so strong. Why was I so totally detached from the drama? What this a problem with the film or with me?

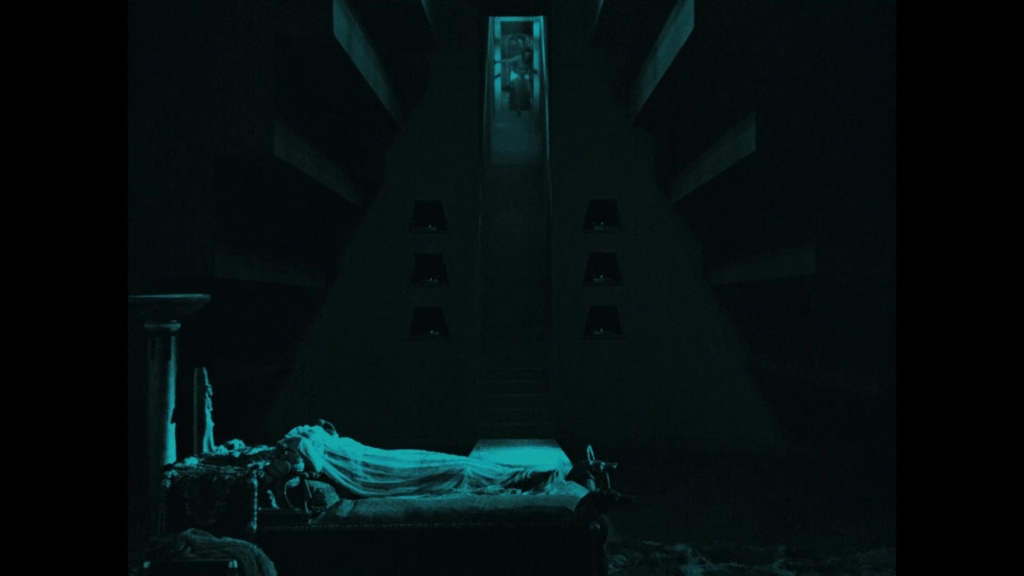

Firstly, the film’s high productions values and superb photography were part of the problem for me. It felt akin to being confronted by one of my local Jehovah’s Witnesses. Doing their rounds, they always dress in their most immaculate suits. Their clothing is never showy, it’s merely tasteful. It’s not a uniform as such, but it defines them, limits them. It’s an invariable combination of immaculate suits, dustless shoes, neatly combed hair, and a tone of voice that is both calm and exceedingly well-rehearsed. This polished smoothness of sound and image is never meant to impress, as such. Rather, the aesthetic is meant to soothe, to calm, to convince. When they open their mouths, the reassurance of middleclass, middlebrow, middle-manager-esque measuredness acts as a kind of anaesthetic for what they’re trying to sell you. As it happens, I’m very bad at telling people that I have no interest in what they have to say, so when confronted by these gleamingly bland, affable people on my doorstep I tend to let them babble away untroubled. (Unlike the Blu-ray of DeMille’s film, I cannot simply press “stop”.) A year or so ago, one of them spoke so long on their chosen topic that their reasonableness eventually gave way to something far more striking: I got conspiracy theories, scatological metaphors, and brutish fundamentalism. I stood, fascinating and appalled, as the man’s charm slowly unravelled and revealed a kind of ideological black hole.

I say all this because my experience stood at my front door, helplessly confronted with two impeccably well-presented religious salespeople spouting sententious homilies, is very much like my experience of watching The King of Kings. The film feels the need to dress in its very best clothes to impress you with its message. If a film’s this good-looking, surely the content must be solid? But it’s precisely the contrast between the well-dressedness of the picture and the dramatic paucity of its every move that annoyed me. You could tell how much money had been spent on everything, on how much time had been spent dressing actors and picking props.

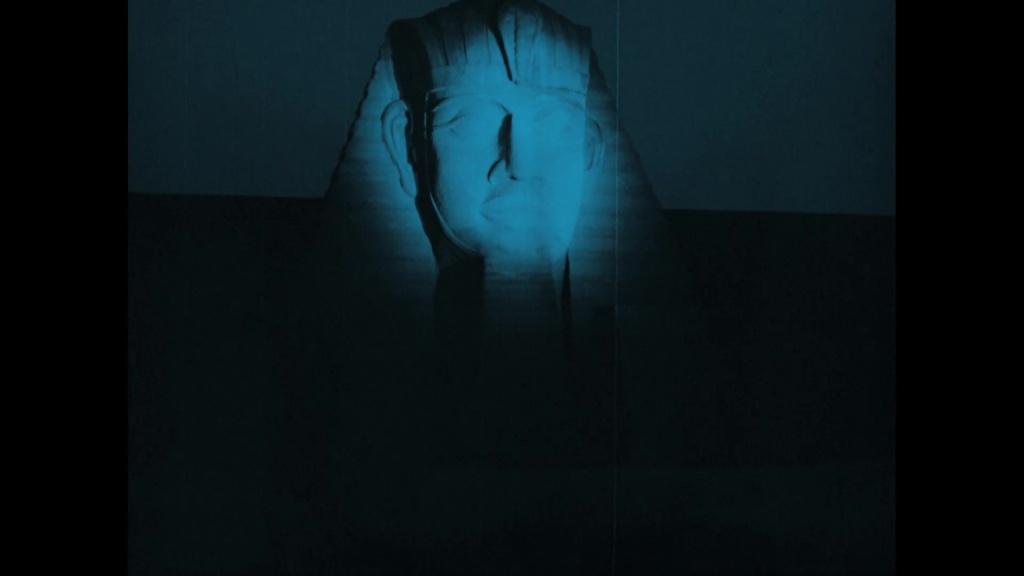

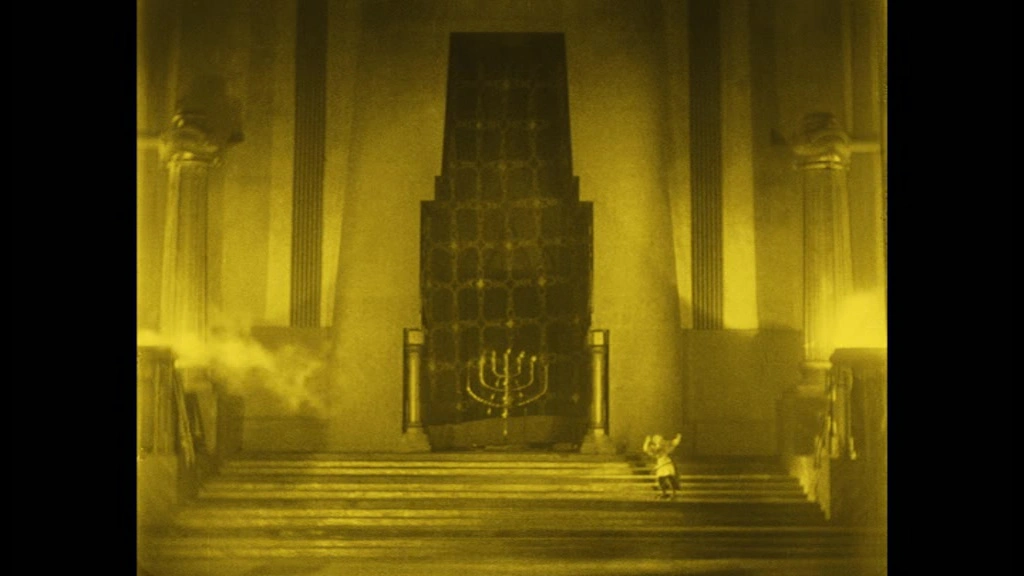

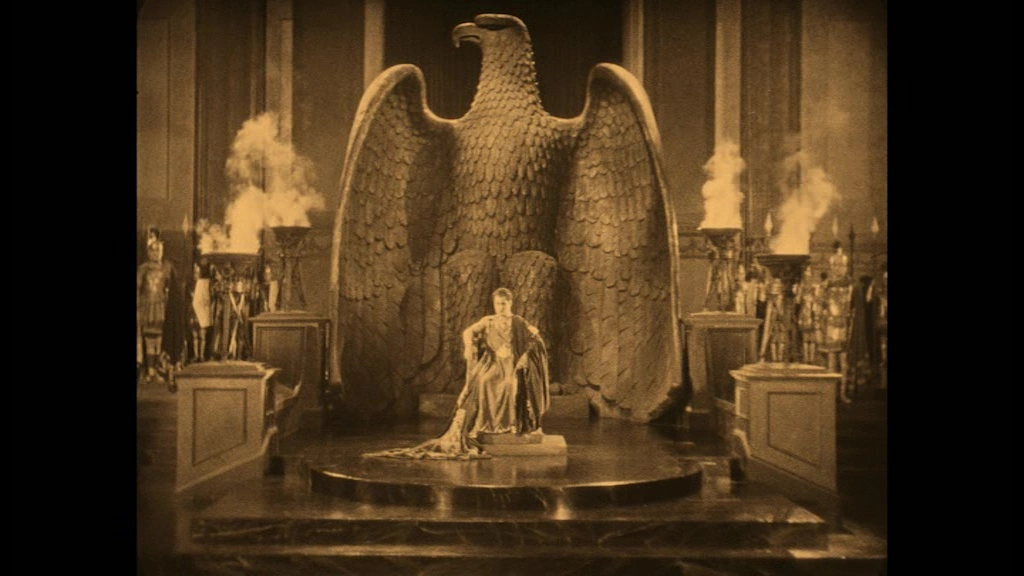

Take the way the Roman soldiers are depicted: they all hang around in full body armour and immaculately plumed helmets, which they seem to wear even when sleeping. They’re all too well groomed, too well fed, too well rehearsed. Or look at the flock of sheep that flees the temple merchants, or the lamb that Jesus fondles later in that sequence. I could almost hear DeMille shouting: “Look at the sheep! Each one hand picked for maximum pictorial beauty! Just feel the quality of these fleeces. You know how much each one would be worth on the market? Let me tell you how much I paid for them…!” The trouble is, everyone on screen is too well attired, too well made up. Every piece of furniture is too well designed, too well finished. Even rags or scraps or fragments of woods are too well fashioned, too well placed. Cripples are too pretty, lunatics too cute. Nothing bears the weight or texture of reality, nor does its fantasy go beyond a kind of bland pictorialism. It’s an illustrated children’s Bible, referencing only the most familiar tropes of Christian iconography or art. Neither aesthetically or dramatically does DeMille offer anything that either wasn’t already a cliché by 1927 or has become one since then—perhaps thanks to this very film. Everything from his sanitized, Aryanized Christ—blonde, bearded, blue-eyed—to his impeccably desexed Mary (Mother of) feels so wearingly familiar, I found it almost impossible to enjoy anything on screen.

What’s more, the drama moves at a slow pace. (Is this what The Film Daily critic meant when he said that the film’s tempo is “remarkable for the peaceful and benign influence it wields on the spectator”?) The film is 155 minutes long, but that’s not the issue. The problem is that every incident is so painstakingly relayed, and so laboriously earnest in citing (literal) chapter and verse, that the drama gets sucked out of every situation. Nothing in this film has bite, or tension, or excitement. The children who are subject to the first instances of Christ’s on-screen miracles are irritating for their cuteness, as is the length of time it takes for their inevitable curing. Soon after, the cleansing of the “seven deadly sins” from Mary Magdalene is already long and absurd without one of the apostles turning to another and explaining to them (and us) what’s going on. Yes, the multiple superimpositions are technically marvellous, but the personifications of the “sins” are ludicrously crude.

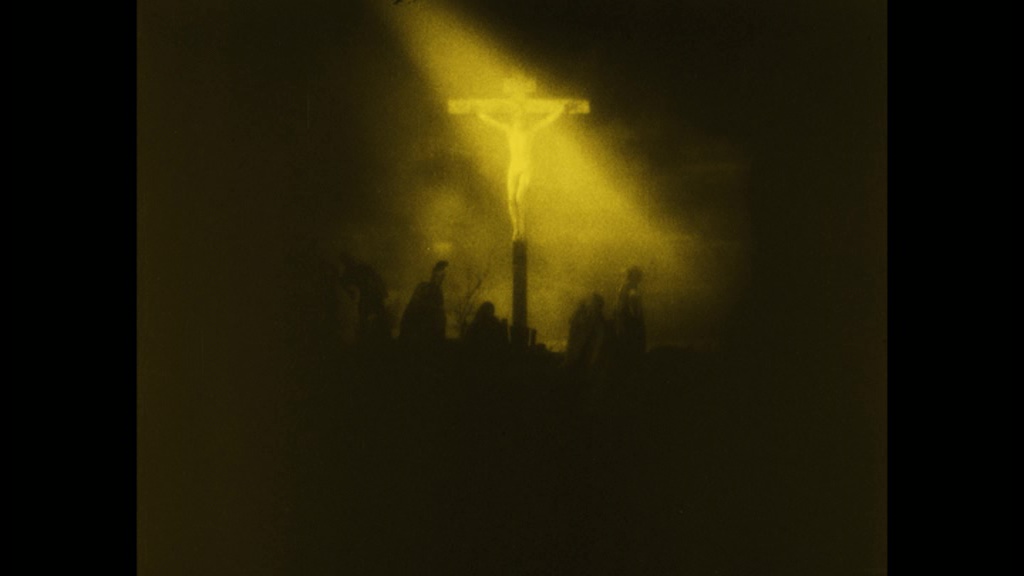

By the time we get to the climax of Judas’s betrayal, I’d grown infinitely weary of DeMille’s painstakingly earnest treatment. Just see how, in the Garden of Gethsemane, Judas goes in to identity Jesus with a kiss. DeMille milks this scene ad infinitum. Judas approaches slowly, moves to Jesus slowly, hovers at his side slowly, moves even closer slowly, leans in slowly, kisses him slowly, reacts slowly, moves away slowly. Poor Jesus has to stand stock still, staring straight ahead, for an eternity—like us, waiting for Judas to bloody well get on with it. The scene is so laboured, its contrivance so drawn out… (Even writing about this scene is tedious—I just want it to be over with!) We come to this scene, as we do to every incident, already knowing exactly what to expect, so to drag it out like this is dramatically absurd. Do something unexpected, Cecil! Surprise me! It’s even more of a shame, since the hand-coloured flames in combination with blue tinting make the Garden of Gethsemane sequence visually extraordinary. Why couldn’t the drama do anything to match it?

Part of the issue is that the film seems to imagine it’s offering us something with profound insight into universal moral truths, but I found it simplistic and superficial. No matter how much backstory the film gives us, I simply cannot believe in Judas as a real human being with real concerns or motives—and thus I cannot believe in the reality of his divided loyalties, his betrayal, or his remorse. Just as all the various Marys on screen are not real women at all, just walking illustrations from a crude book of dogma. And none of this is helped by the way the film uses endless biblical citations as dramatic punchlines to scenes. It ends up smacking the viewer as a kind of narrative (not to mention moral) smugness. This is a film that feels superior to (all but one of) its characters.

If the above makes it sound like I got nothing from the film, this is not quite true. Amid the pomp and platitudes, H.B. Warner gives a very restrained and (within the film’s own terms) rewarding performance as Jesus. He manages to be dignified and sympathetic even when the film around him is not. Both the role itself and the screenplay allow Warner little room for psychological or emotional complexity. He is caring, or sad, or knowing-yet-forgiving. He’s also miraculous, in a way that is oddly unimpressive. When DeMille’s Christ waves his hand to heal the sick, there’s no suspense, no emotion. The effects (like the soldier’s vanishing wound in the Garden of Gethsemane) take place too smoothly, or too swiftly. They’re so miraculously effortless that they are no longer miraculous. (And no-one in the film ever pauses to question the motivation or context of these miracles: like absolutely everything else in the film, they are meant to be received without a scintilla of scepticism.) Given all this, Warner’s eyes are often the source of the only real emotion in the film—even if these emotions (pity, love, resignation) lack any kind of human context. Jesus as a character is merely Christ the symbol. He might walk around and interact with people, but a real human being—as an individual with a human consciousness or a personal history or a complex inner life—he is not. Warner does his best within the many limitations put upon him.

If DeMille cast a very un-Jewish-looking Jesus, he did cast two actual Jewish actors in prominent roles. The father and son actors Rudolph and Joseph Schildkraut were Austrian emigres who had come to the US at the start of the decade. In The King of Kings, they respectively play Caiaphas (the High Priest of Israel) and Judas. The former has the less nuanced character: he’s all bearded malevolence and unrepentant scheming. But as Judas, Joseph Schildkraut has more work to do. It’s a shame that the script’s effort to give him some kind of backstory makes his character less interesting than he might otherwise be. DeMille makes Judas a power-hungry schemer, eager to gain influence (and affluence) once he has installed Jesus as king. Making a villain more villainous does not make him a more interesting character. Joseph Schildkraut’s performance is as mannered as his character is simplistic. Ne’er has a man been seen to so shiftily fondle his cummerbund in villainous contemplation. In the Last Supper scene, the breaking of the bread is a cue for more scurrilous shifting on Schildkraut’s part. He resembles a schoolboy faced with unpalatable food (I’ve been there), who must pretend to eat his portion while secretly depositing it onto the floor. We are presumably meant to take against him from the outside for being dark-haired and clean shaven. Once things get serious, Judas’s hair becomes tangled—as if this could in any way make his character arc more convincing.

Of course, casting the two main villains in the film as Jews is not exactly sensitive. DeMille is also nasty to both the Schildkrauts at the end. Judas, per the tradition, hangs himself. Though we don’t see him do so, we see his swinging body tumble into the abyss, courtesy of the clunky earthquake that intervenes during the crucifixion. Meanwhile, Caiaphas falls on his knees at the temple: “Lord God Jehovah, visit not Thy wrath on Thy people Israel—I alone am guilty!” For once, there’s no biblical citation. DeMille is at least more courteous here than in the similar scene in Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ (2004), which (in)famously takes the opportunity (via Caiaphas’s dialogue) to pass the blame onto the entire Jewish people forevermore. DeMille wants to have it both ways: cast Jews as the villains yet insert an excusatory note. The note is meant to excuse the Jews, but it’s also an excuse for DeMille. Like Pilate, he washes his hands.

The rest of the cast is uniformly uninteresting. Among the disciples, only Peter (Ernest Torrence) stands out, though not for good reasons. His alternately comedic and sincere characterization hits every note so squarely and obviously, I immediately took against him. I know it’s part of the New Testament story, but the way Peter is told that he will deny Jesus three times, then refutes this, then is proven wrong, then acts repentantly, is the perfect example of how the film fails to deliver any novelty, any friction or doubt, in its adaptation. What is meant to be the tragic fulfilment of Jesus’s prediction comes across as almost comedic on screen, such is Torrence’s eye-bulging doubletake. It’s a kind of visual “D’oh!” Likewise, the film’s laborious setting-up of the moment, and equally laborious explication of the punchline, is another instance of dramatic smugness. But at least I can remember Peter. The rest of the disciples are virtually indistinguishable. They have no personality, no inner lives, no function beyond the affirmation of what we already know. (In the liner notes of the Blu-ray, Lobster include a wonderful advert for the film in which the whole cast appear to swarm around the central figure of DeMille. Such is the size of font and layout of the design that it looks like the “King of Kings” is DeMille himself!)

If the adults are too often piously bland, the children are worse. I would like to restate how irritating I found the children in this film. They’re part of the ingratiating way the film seeks our sympathy, the way it hopes to humanize the story. Thus, the soon-to-be New Testament author Mark is a picture-book pretty child equipped with an enormous crop of curly blond hair—a cliché of fresh-faced cuteness that instantly made me take against him. Not only does he introduce us to Jesus via another child (a blind boy, who is likewise fair-haired), but he’s there right to the end. It’s he who encourages Simon of Cyrene to take up the burden of Jesus’s cross in the penultimate sequence. This is another of DeMille’s biblical amendments, since the scriptures state that it was the Romans that “compelled” Simon to carry the cross. Why the amendment? Merely to squeeze our sympathy glands again?

But was I really this annoyed by the film? Did it never affect me? Was I entirely unmoved? Hmm. Well, no. I did find moments moving, but this was often more due to the choice of music. For Lobster’s restoration of The King of Kings, Robert Israel used Hugo Riesenfeld’s orchestral score (as recorded for the synchronized 1928 version of the film) as the basis for his own adaptation. Copying Riesenfeld’s cues from 1928, he expanded the music to fit the longer 1927 version. I will have more to say on the score shortly, but for now I just want to point out how particular pieces of music seemed to make something more of the film—at least, for me. Take the Last Supper sequence. I’ve already said that I find the handling of Judas in this scene clumsy, but at the end of the sequence Riesenfeld introduces music from Wagner’s Parsifal (1882). It’s the opening of the Prelude to Act I: a soundscape of shifting, unresolved harmonic tension that hypnotically ebbs and flows—it’s music of unworldly beauty, of abstract sorrow, of unfulfilled longing. As rendered for Israel’s modern recording, the music is reduced for a smaller orchestra than Wagner intended—but it still sent shivers down my spine. And though the music doesn’t sound like it should in better performances by larger orchestras, and though Riesenfeld cuts and pastes from other sources as the scene proceeds, the effect as a whole is still superb. For once, something unearthly creeps over the picture. But then, inevitably, a voiceless choir comes in at the end of the scene with the melody from “Abide with me”, and the effect is ruined. From late romantic mysticism—all unsettled harmonics and soft, swirling rhythms—the score crashes to earth with resounding cliché.

That said, I did find Israel’s adaption of the Riesenfeld score very impressive. What’s most remarkable is its fleetfooted switching from one piece to another. Rarely does Riesenfeld see out a whole movement from its original context. Rather, he will use a single iteration of a theme, a single phrase, then segue rapidly to another piece. Thus, we sometimes get the “Dresden Amen” theme (usually as orchestrated by Wagner in Parsifal) in the brass, but the entire thing lasts one or two bars. It makes its point, then moves on. Later, we get more from Parsifal—but only a few more bars, just enough to introduce the right mood for the moment. Pontius Pilate gets the anxious, unsettled opening of Rimsky-Korsakov’s “Antar” symphony (1868, rev. 1875/91), but only the opening—again, Riesenfeld moves on to something else to follow the action on screen. Even the way he unleashes music from the finale of Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique (1830)—surely the most extrovertly wild and exciting music of the entire score—he does so only for a few measures during the scourging of Jesus by the Romans. There are even smaller touches, too. I loved, for example, the delicious way that tambourine strikes accompany the silver pieces falling in a pile before Judas.

Sometimes the brevity of the cues works against their effectiveness. Thus, during the crucifixion sequence, Riesenfeld uses music from the last movement of Tchaikovsky’s sixth symphony, the “Pathétique”(1893). But he reorchestrates it so that the music is less effective than in the original. The original is an extraordinary unwinding of orchestral timbre, the whole movement slowing and deepening and darkening—occasionally lashing out in fury—until the music peters out in the depths of despair. With Riesenfeld, we get a much steadier tempo and rhythm, and the musical narrative of the movement—from anger to oblivion—is cut short. Equally, the way Riesenfeld chucks in some Verdi (the dies irae from his requiem (1874)) for DeMille’s earthquake feels as clunky an imposition as the earthquake itself.

My other reservation is not about the music but about the 2016 recording for the film’s digital release. I can never fully detach my comments from what is inevitably a kind of snobbery, but nevertheless I really do think that there isan issue of quality at stake. When citing well-known musical themes, it is very easy for scores to sound tired and cliched. What makes or breaks the use of such music is the way they are arranged and performed. For example, several cues used in the Riesenfeld score for The King of Kings are also used in the (anonymous, c.1930) score for Die Liebe der Jeanne Ney. Modern renditions of both scores were arranged and recorded almost at the same time, in 2016-17, for their respective digital release. But despite sharing some of the same music, the two soundtracks are very different. Bernd Thewes (for Jeanne Ney) orchestrates the score in such a lively and interesting way—and the music is performed and recorded with such immense panache—that the effect is quite different, and more effective.

Of course, Israel’s forces are smaller than Thewes’s: Israel has the Czech Cinema Orchestra, while Thewes has the WDR Funkhausorchester Köln. My search for “The Czech Cinema Orchestra” yielded no results online. There is such a thing as “The Czech Film Orchestra”, however. As I surmised in an earlier post, Czech orchestras are popular with soundtrack composers for their competitive prices. As the homepage of the Czech Film Orchestra states: “We can offer you world-class orchestral recordings for 25% of the cost of a recording in the USA, Canada, or London.” Is the “Czech Cinema Orchestra” a budget version of the Czech Film Orchestra? I presume it’s a scratch band assembled for the 2016 recording. The performance—especially, of the strings—is less well drilled than it could be, and less atmospherically recorded than more budget-enhanced silent film soundtracks I’ve heard. (For examples of the latter, see: just about anything produced in Germany through ARTE, or any soundtrack produced by Carl Davis.)

It’s a shame, as Riesenfeld’s score does a lot of the heavy lifting as far as mood and emotion are concerned in The King of Kings. When the music really needs to land, it often doesn’t. During the resurrection sequence, DeMille’s Technicolor glows with gorgeous lustre—the music needs to do likewise. Yet I don’t think I’ve heard a less convincing rendition of the prelude to Act 3 of Tannhäuser (1845) than the one given here, per Israel’s performance. The string section, in particular, can scarcely keep together for the swirling crescendo that leads to Jesus’s miraculous reappearance. What should be a sonic whirlwind is something of a whimper.

In summary, I’ve not been so irritated by a silent film in a long time. I find DeMille a very frustrating filmmaker, especially when it comes to his religious (or religiose) productions. Oddly, I almost wished he’d do something outrageous with the narrative of The King of Kings to make it more interesting. The only temporal interpolation he offers is at the end, when Jesus appears to loom over the skyscrapers of the modern world, offering his love. But the effect is banal. Compared with other biblical screen worlds of the 1920s (and even those early Passion films of the 1900s), The King of Kings never gripped or surprised me. Neither realistic nor magical, for me the film offers very little that would make me want to sit through the whole thing again—even if I thought I could bare it. I can see how audiences at the time might have found themselves drawn to its reverent portrayal, and I can appreciate the effort that has gone into its look. The photography is superb, the lighting lovely, the Technicolor gorgeous. But a film can look like a million dollars and still feel impoverished.

Paul Cuff