The second part of Day 2 takes us to two very different silent worlds: a haunted fairground populated by marionettes, and a snow-bound urban apartment populated by a working-class family. I confess I didn’t have the time to watch the filmed intros today (or any day) so I cannot tell you about the day’s themes, only reflect on the films themselves and how they (one, at least) link to previous films in the festival…

Die Grosse Liebe einer kleinen Tänzerin [Das Kabinett des Dr Larifari] (1924; Ger.; Alfred Zeisler and Kictor Abel)

This is a terrifying film. Though the film’s given title (The Great Love of a Little Dancer) offers little sense of its content, it’s alternate title (The Cabinet of Dr Larifari) is a clearer signal to its style, mode, and method. Here is a nightmare version of a nightmare film: a doll’s hallucination of Dr Caligari.

The world is immediately recognizable. Recognizable yet different. A distorted version of the distorted sets of Caligari. It’s a misremembered recreation of the earlier film. It’s a dream recalling details but not the whole, or the whole but not the details. Where are we? Glimpses of a city behind the fair. We are on the fringes of another reality.

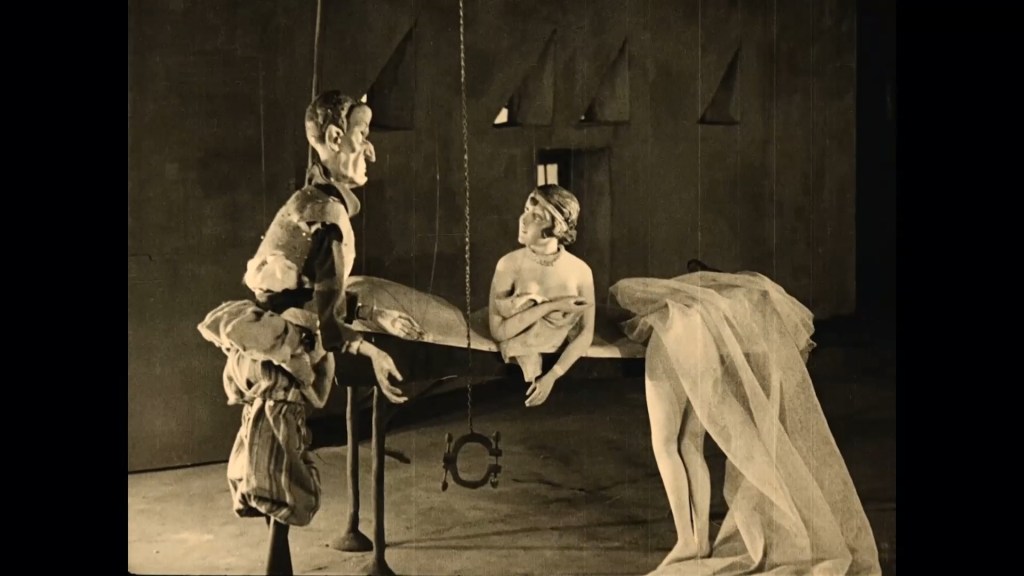

Here are grotesque figures. Distended torsos, bloated bodies, elongated legs, scrunched faces, squished heads. Spiderweb lines tingle from their limbs up to the top of the frame. Mr Adolar is a thin, pinched voyeur. Esmerelda is not grotesque, tough her gentle smile is just as carved as Adolar’s smirk. Adolar tickles her chin. My skin crawled. Everyone walks slowly, awkwardly. Which is to say they do not “walk” as such. They are led, guided, controlled. The awkwardness is inherent in this world. Like the painted sets of Caligari—where even light and shadow are unable to move, to escape that dreadful, fixed world—the dolls of Larifari move without will. They move slowly, unable to provide their own momentum.

Larifari stares jealously. He always stares jealously. He can’t help it. Jealousy is furiously inscribed in his face. His face has no other expression, no other purpose. He is there to be jealousy.

There are characters with extendable legs, jack-in-the-box spines, punch-bag faces.

Here is Leonidas, Esmerelda’s line-tamer lover.

And here is his lion. A talking lion with possessed eyes. A terrifying companion. A companion who follows with an absurd leaping step. Like a giant flea.

Larafari is frightened and so falls into a bucket. Low comedy turns sinister. Larafari swears eternal revenge. Of course it will be eternal, he cannot change. His motives are as fixed as his face, his spine.

Superimposed vision of Larafari in Esmerelda’s room. A curse: Every man who comes near her will have their head literally turned. His words come in a jumble of rearranging letters. Yes, the text is animate: but the letters march and wheedle like dolls; even punctuation performs jerky, awkward, acrobatics.

Here is a man like a mashed pumpkin who lifts weights. Here are Knockenmus and Bruchspinat (Bonepulp and Brokenspinach). The names are ciphers of a childish nightmare. They are an infant’s plate of mashed food come to life.

The curse takes hold. The head-turned victims must visit Professor Mordgeschrei (Pr. Deathknell), the Miracle Doctor. Why must they visit him? Why is there no other recourse? Because! Because there is no reality beyond the frame. There is no city beyond the fairground. As in Caligari, there is no escape. The film gestures to a space beyond without ever suggesting it exists as a reality. The outside world is a painted flat, a model. The sky is painted. The horizon is an infinite impossibility.

Dolls with backward heads twitch and writhe. The doctor’s lair opens its moustache-mouth door. The doctor assembles himself: it is Larafari! Esmerelda reveals her second face: one of fixed terror. There can be no transition between expressions. Each is fixed, with the threat of permanent fixity. Transition is for the living.

He decapitates then re-capitates the circus folk in a crude head-swap operation. (Even the grammar of the frame aids and abets him: masking the heads in three dreadful vignettes, surrounded by darkness.)

Meanwhile the lion is being tortured by its tail trapped in the door and endlessly elongating. (Yet I can’t bear the thought of it escaping, of coming in, of appearing in the scene in order to “help” me.)

Esmerelda is naked. Her stiff hands cover herself. Is she tied down? I cannot tell. But it matters not. A different logic is at work.

Larafari has a saw. He approaches.

Thank god we don’t see the operation. It is an unthinkable process.

Esmerelda is sawn in half, but still she takes care to cover her breasts. What dignity is left to her?

The lion attacks Larifari and makes him scatter his limbs. Is he dead? Or can he escape the limits of his own construction?

Esmerelda has lost Leonidas. In despair, she commits suicide by falling off the bed and shattering.

But it’s all a dream! Or is it? No, it’s all a film. The dolls are put back into their Piccolo Film coffin.

As I said, this is a terrifying film.

Just Around the Corner (1921; US; Frances Marion)

The Birdsong family live in a poor district of the city. The widowed Ma has a heart condition which will soon kill her. Her son Jimmie is a young lad on the cusp of manhood. Her daughter Essie is dating a young huckster, Joe. Ma hopes Essie will marry, and worries for both her and her son providing for themselves when she is gone. The film is an interesting counterpart to Yes and No: more successful in some regards, less in others. There are no stars here, the most famous name being the film’s author-director. But the emotional success of the story, manipulative though it is, crept up on me slowly and surely.

Yes, this film has “Scenario and direction by Frances Marion”. Another woman’s name at the head of a picture, adapted from a story written by another female author. And the film has the same intelligent female eye for detail, meaning, for social pressures.

Here are glimpses of the city streets. Real faces, real bodies, wrapped up. Rich photography, clothed in rich tinting.

Ma (Margaret Seddon) can frown and smile at once; love and worry are one and the same. As with Norma Talmadge’s character of Minnie, it is the moments when Ma is left alone that move me. There is her pain when Jimmie leaves without kissing her goodbye, and her gladness when he returns and they embrace. (And there, in a picture frame on the wall, is a photo of her with her lost husband. It’s never highlighted, but there it is, the past—her past—present in the background.)

The film’s painted title designs are most tasteful than Yes or No.

Essie works in a flower shop. The lighting is beautiful, but the work is visibly hard. (I recognize the same real hands that are in the flower shop scenes of Kirsanoff’s masterpiece Ménilmontant (1924).) The texture of hands roughened, hardened, darkened by labour. The texture of human skin. Real faces. A curious sensation: the sheer beauty of the photography and tinting, and the harshness of the work on screen.

This is a film that knows how its world—our world—is run, and who runs it: the boss evades the law by getting his women to work at home on Saturdays. The boss is also predatory. Jimmie tries to be a man. His gait is forced. He looks absurd. He is trying to help. The boss feigns a punch. Jimmie recoils. Essie placates the boss. The world runs as ever.

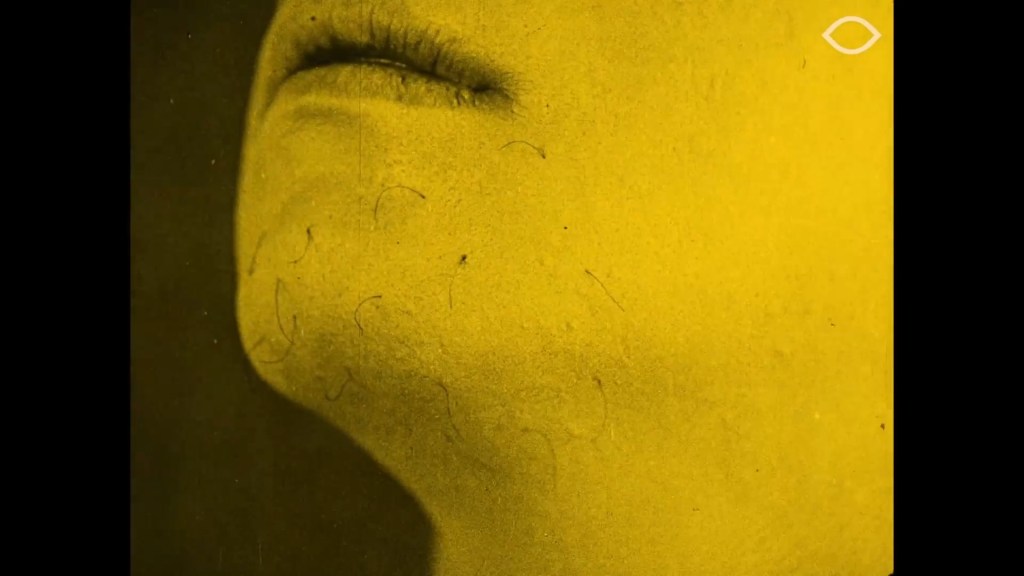

The print is superb, but here is the first sign of real decay. The films mottles, becomes blotched and bleached. Decay flickers over Jimmie’s face when he tries to stand up to his boss. He is trying to look like a man, to make time artificially speed up. But here is the real sign of passing time: the boy’s face is being eaten away by the death of celluloid. His face is long eaten away by now.

Ma is at the window. A capsule of sadness. (I wished the sight of her here had lingered, her loneliness is so tragic.)

Jimmie tries to force himself to be a man. He shaves. Essie: “What are you shaving Jimmie, your eyebrows?” It’s a great line, followed by an intrusive, weird closeup of a few hairs on the boy’s chin.

Lulu is Essie’s friend, but we distrust her immediately: she’s dressed up, judgemental of Ma. Her carelessness is hurtful. When she disparages Ma (“You certainly forgot the ‘Welcome’ on your doormat, dearie”), she insults us. When Lulu gets Essie a job as an usherette at a theatre, Ma is upset: “It’s night work, I’m afraid of it”. There is something unsaid here, an experience unrelated by Ma. It’s a nod to the position of women and their exploitability. We’ve already seen how Essie’s boss behaves. Nothing is spelt out, but it’s there, lurking outside the safety of the frame.

Lulu makes up Essie for her role, and Ma frets again: “It’s not about lipstick—it’s what it might lead to.” It sounds absurd, but Ma speaks as a figure from an earlier generation, the generation voiced in Griffith’s Biograph films, where fears of being a “painted woman” and all that might imply are explored in numerous scenarios. It’s also a worry about how men will read Essie. Ma wants to obey one set of rules (voiced by her, but set by men) to not fall foul of another set of expectations (again, set by men). And on the mirror behind Essie is a photo, indistinct, of her father.

Now we meet Essie’s boyfriend, first via a photo she has of him. It’s a ludicrous pose, a ludicrous look. He is comic, but is he more than that? He first appears in the flesh trying to impress his peers by balancing a hat on his nose. Now he’s hawking tickets at inflated prices to a man in a shop. He’s a wrong’un, no doubt.

We are in the changing room of theatre. It’s a feminine space, but it’s overlooked by the male space of the dark street alley—where men can tap the caged window to get there attention.

Essie is taken to “a sixty-cent restaurant”—a cost-based denomination that Balzac would have appreciated, describing a life through a balance sheet of daily costs and expectations. (Balzac: “We only resent spending money on necessities.”)

Will Jimmie come home to meet Ma for the first time? Ma hopes so. Her children are out but she tells her neighbour and cries because she is happy. Like her frowning smile, her joy is expressed through a means shared by sadness.

Joe avoids all talk of marriage. He whistles as Essie leans in to press him on the issue. His character is played for laughs, at first, but it’s clear that the laughs are expressive of his entirely superficial nature: he laughs off all responsibility. His laughter grates, his lightness irritates, angers.

When he reaches the Birdsong apartment, Joe stops at the entrance. He says he has a celluloid collar and worries: “the fireside ain’t no place for me. I might blow your mother to smithereens!” It’s a good line (though I now resist laughing at anything this foul character says or does), but I immediately think of Jimmie’s face blotched with decay. The character refers to the medium that captures his life on screen: a life that is flammable, dangerous, at risk of instant disappearance.

And yes, of course he runs off without coming in. And it’s so hurtful. We’ve already seen him flirt with another woman; he lies, cheats, he’s a coward. The film is squeezing my outrage gland. It’s difficult to resist.

“Winter is beautiful to fur-wrapped you and me…” an intertitle states. An interesting assumption about our class, compared to the characters. Winter is beautiful and harsh on screen. It’s real snow, real snow piled up on the streets. It looks beautiful but we see what it means to have to slip and slide across the street and huddle in doorways and shops to keep warm. Essie doesn’t want to put on a warm coat because it doesn’t look fashionable—fashionable, that is, accord to men’s tastes—and because it’s not the done thing to have a cold.

Ma is on her own again. Her whole body sinks under weight of her illness, her sadness. She is alone with a lamp, putting on rouge to look presentable to the boyfriend who will surely never turn up. It’s another tragic little vignette, so telling.

Where are Joe and Essie? They are dancing in a competition, and Joe blames her for losing. He ignores her requests, and she knows it—yet still she tags along, and I hate Joe all the more for it.

Ma and Jimmie are at home. She imagines Essie’s “beau” as like her husband, and the image of her son’s future. It’s a weird dynamic, imagining all the male figures in her family as father-figures. But I take it to be the depth of her feeling for her lost husband. Everything links back to him, to the loss of him. It’s this sense that takes hold of the last scenes, and is so moving. She has led a whole life up to know that we never see, but now we glimpse something of it, its intensity, its depth.

Ma is on her deathbed. It’s the only time we see her with her hair down. It looks darker, looser. Jimmie worries about her, saying she looks “queer”. In fact, I think she looks young—her hair falling over her shoulders and the pillow. Yet she looks afraid, too. (And yes, I’m welling up at this point, and even now, rewriting my notes.)

Essie is running through the snow to chase Joe. Ma has said that it would kill her not to see him now, of all nights. She has forgotten her coat, but it’s too urgent to go back. She chases Joe down. “Let her die”, he says, and my god finally Essie slaps him.

I was already in the grip of the film, but when a stranger offers Essie his coat on the street and she brings him back home… well, yes, I was crying in spite of my reservations. It was nice to see an act of unapologetic kindness on screen. The stranger sits down on the bed, holds Ma’s hand. “Ain’t she pretty?” Essie says, and the stranger strokes Ma’s cheek. (Even as I type this, my description sounds mawkish. No doubt the film is mawkish, but I’ve given up pretending I had “critical distance” at this point.) “It’s a strong hand like Papa’s was, Essie. It makes me feel so good.”

The new family have dinner, the stranger being the kind of male presence lacking in these women’s lives: kind, gentle, unthreatening. “You are just like their father—big, strong and friendly…”, says Ma. It’s another glimpse of Ma’s past, long gone—and it’s such a gentle scene, her death. You can’t help feeling she deserves this last illusion, that the sensation of the stranger’s hand on hers has been years in coming.

The final scene—of the spring in which we see Essie married to the stranger—is a little comic and a little sad. It is homely. Yes, we’ve arrived at home at last—but there is Ma, just a photograph on the wall, absent—just like the photograph on Ma’s wall of her own husband, absent.

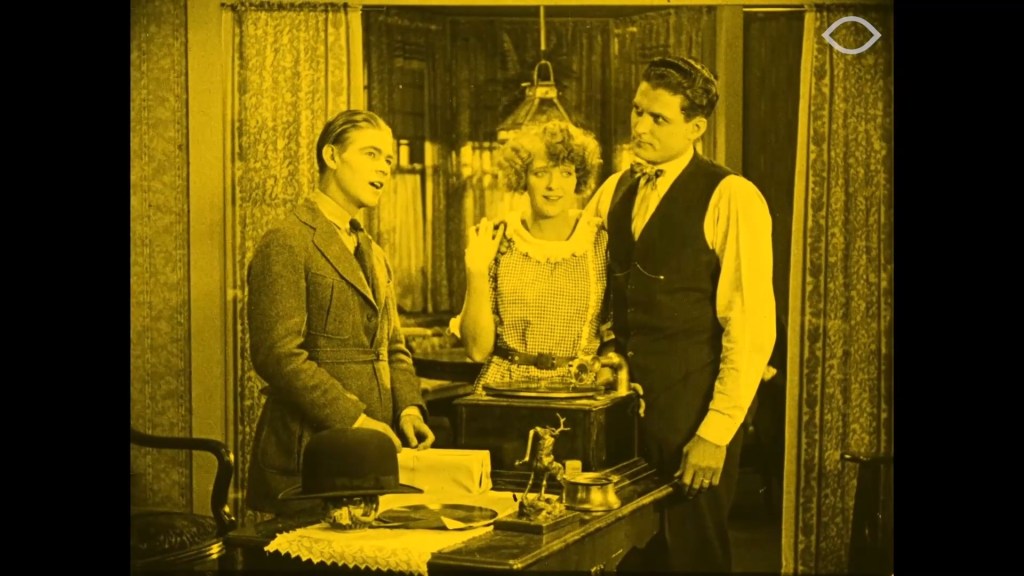

The last moments of Just Around the Corner make an interesting companion to Yes or No. As in the latter, in Just Around the Corner Essie puts on a record. They sing together. But there is no complexity here, no ambiguity. Yes, there is sadness, but it’s a neat kind of sadness. There is no hesitation about what the film has meant, or what the new family means. The future is settled, uninteresting. Yes or No offers doubt and leaves you thinking. Yes or No is a more sober film, if a less moving one than Just Around the Corner.

Paul Cuff