Some real central European kingdoms today, as we visit Slovenia and Slovakia with a short travelog and a long ethnographic documentary…

Kralj Aleksander na Bledu (1922; Yug.; Veličan Bešter)

The title gives it away: here is King Alexander I of Yugoslavia visiting Bled. In fact, the land precedes the monarch and is far more interesting.

Here are turquoise mountains and skies and lake. Trees in the heat of celluloid haze. Cliffs, spires, sails. The camera wobbles, turns its neck with difficulty. It feels the motions of the waves. It is being operated unsteadily. It cuts. Pans. Repeats. Now we have our feet on land. Green gliffs and peaks viewed through trees. Higher still. The turquoise lake. Then the chateau, orange; closer, further away; then green.

Suddenly, dismounted hussars march towards us in a vivid orange tint. The film sheds its colours and indiscipline (and yes, much of its inexplicable charm). A train approaches and the men, now neatly arranged in monochrome, await the King. An anonymous little man in officer’s uniform marches one way, then another. It’s the King, apparently. A dog ignores him and scurries, nose-down, over the tracks. The King inspects the troops, their eyes straining right. The film ceases.

Po horách, po dalách (1930; Cs.; Karel Plicka)

The title is from an old folk song, “Over Mountains, Over Valleys…”—and this is where the film goes. It is the past, caught before it disappeared. It is the people, caught before between two world wars.

Trees tremble in the wind. Sheep appear, guided by men—their trousers the colour of the grass, their shirts the colour of the clouds. Children’s faces against the sky. Children whistling, playing the pipes. A dog nestling against his knees.

The film moves at the pace of life in the mountain pastures. The sheep pen closes. The sheep press close. Clouds move in the distance. The shepherds eat. Look at the texture of their clothes, faces, hats. Sun and wind and cold have given them their complexions, complexions whose grain settles into the texture of nitrate.

The men make mugs, vessels, belts. They put on their shoes, they wind the straps. This is the way feet have been bound for centuries, millennia even. They mould sheep cheese in wooden presses, grinning as they reveal dairy reimagined into ducks.

A village. Women dressed for church. Children as miniature adults, the same clothing, following the same steps.

Musicians play extraordinary tubas on rocks. They dance. Violins play. (And surely we’re missing a great deal by having just a piano accompany the film. Imagine the effect of the instruments on screen being played in the theatre.)

Strange rituals, games, all under the vast sky, against the hazy mountains. Girls play horses. Boys play carts.

A bagpiper at the centre of a moving throng of children dancing, waving, clapping. Extraordinary athleticism of diving, tumbling, wheeling, climbing. Bodies writhe and wriggle and flex. And all against the vast landscape. Children become frogs, animals, insects with multiple limbs. Boys become barrels. They are watched by little sheep, who must wonder at the strangeness of human beings.

Corpus Christi. Swathes of people pressed together. Banners. Poles.

A cradle in the fields. A mother and daughter sing a lullaby to the infant.

But now the men and women are marching with rakes and symbols. Women dance around their landlord.

By the Váh River. Geese wander. A woman washes. Bride and bridesmaids. The bride in close-up, but the camera sees her enormous costume—a peasant girl dressed like a cross between Queen Elisabeth I and an Aztec deity; she stands facing the camera, then in profile. She is grinning, embarrassed. Carts pile high with guests, cushions. There is a manpowered merry-go-round at the centre of celebrations. The operators must get as dizzy as the occupants.

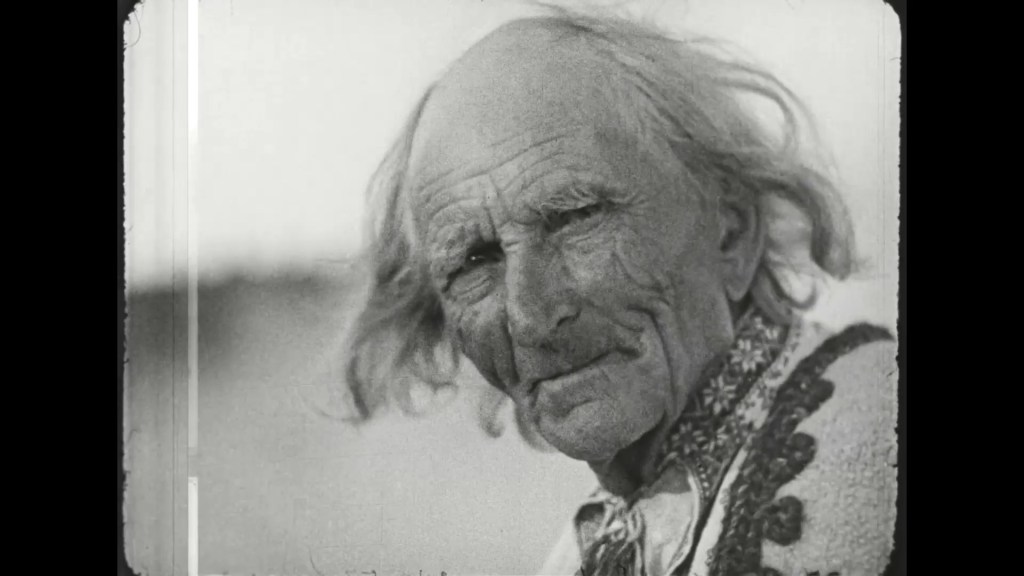

An Orthodox pilgrimage of Slovenes into Russia. Banners, endless genuflecting and crossing. Beggars, old men, priests, women sat on the grass. The past and its people mill about. Ancient old men, tiny boys. Men with hair and pipes. Men who are all hair, creases in their face. A crucifix is wreathed in flowers. Boys climb a wooden frame and ring a bell several times their size.

A farm. It is Sunday. Families walk. A bride is dressed. We watch her headdress assembled. Peasant faces, too sincere to smile. Sandalled feet over ancient cobbles. Past the churchyard, overgrown with tall grass. Figures in white sit among the crosses. Prayers are said above the graves. The land looms over the tombs, over the kneeling mourners.

An ancient piper. Tiny children with blonde hair, straw hair, hair like fresh grass. A group sits on a knoll, their feet higher than the rooftops below. Mothers and children sway. Boys prance and dance, leaping with unbelievable athleticism. The boys become men, who dance in the smoke of a fire. A sword dance of lethal precision and timing. The musicians bite on huge pipes as they play their violins. The band marches forward, the dancers recoil.

Hemp is being made, under the eyes of a matriarch with rake, pitchfork, and sickle. (The flies crawl on her warm arm.) There is embroidery. The striking patterns of the women’s dresses being made by their hands. A child watches her mother sow. Cloth is washed, beaten, hung to dry.

“Studies of folk clothing and types”. Bodies and faces and smiles under that great sky. Grinning and shyness.

Children’s games. Inexplicable routines.

The Belan Alps. The shadows of clouds rush over mountain pastures. Rivers sparkle. Rock gleams. Clouds pass over dark peaks. Stunning views, grass banks follow the immense folds of rock and earth.

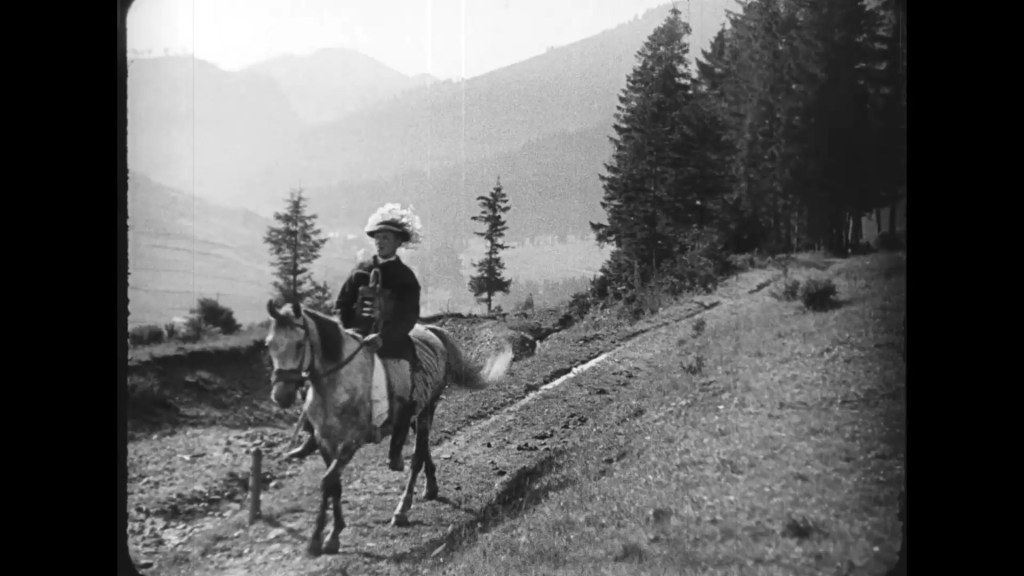

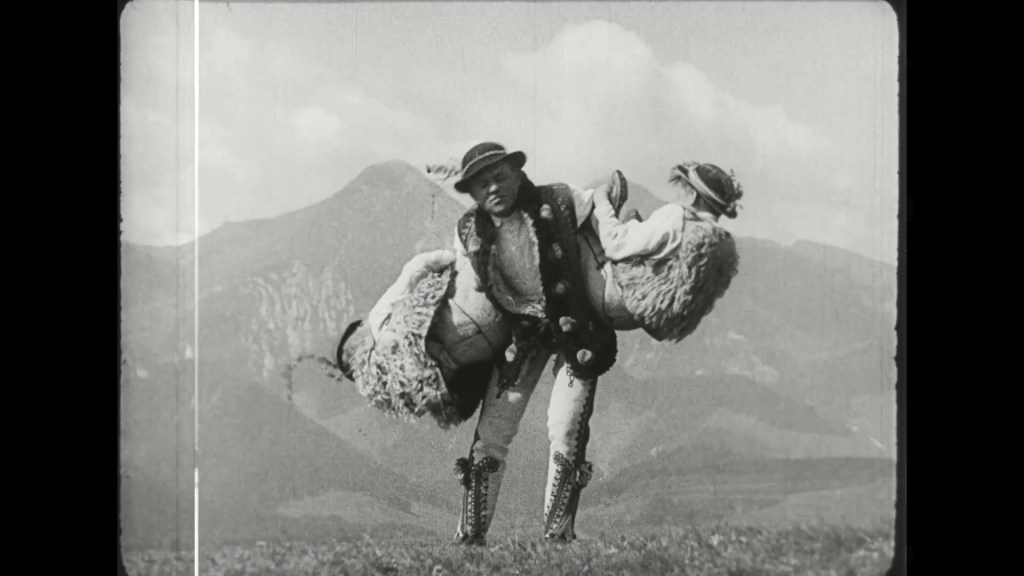

And there before it all are the farmers, cutting and harvesting the grass, sharpening blades, spinning wool, processing flax. Wooden tools, wooden looms. Dexterity passed down over centuries. Highlanders’ music, costumes. A horse and rider against the astonishing backdrop. Sheepskin jerkins, men dancing. Beechwood chopping: boys are woodsmen, axe, and tree at once. Men are lifting one another, twirling around, fighting on benches, barrelling down the hill in ones and twos, and threes, and fours. Children lifting other children with just their legs. These are bodies with years of labour already in them. Cows wander past the twirling acrobatics of the shepherds. A game called “train engine” in which bodies are the carriages and engine. But how many of them have ever seen a train? “Strength in the legs”, “Strength in the hands”, “Pulling tomcat”. “Flipping the boys over on a stick”, “Doing the horses”, children riding atop children riding atop children. “Tying to the stick”, children turned into knots. Adults carrying bundles of children across a grassy ridge, behind them the mountains. The film stops, but it could go on forever—if history were not inevitably to intervene.

What am I to make of all this? The film has a hypnotic rhythm to it. Everything is presented with very little comment. Filmic interventions are chiefly noticeable in the details: when the people step forward for the camera. But in these instances, you can sense the real emotions: embarrassment, amusement, awkwardness, reticence. Yes, the people are performing for the camera, but they’re clearly performing for each other as well. There is a rough-and-ready feel to even the most elaborate scenes. And everything takes place before the immense landscape, on natural stages that both ground the inhabitants and stretch beyond them. These are lives led on unending swathes of grass, under enormous skies. This is not the managed poetry of a Dovzhenko, but a looser assemblage of faces and landscapes. People and places determine the film’s shape, its rhythm. And I love watching these silent folk in these silent spaces. The majesty of a tangible reality, removed from our grasp and set apart from our time.

Paul Cuff