Well, it’s been cold lately, so I thought I’d watch something icy. I’m a sucker for anything that calls itself (or has retrospectively been called) a “mountain film”, and the fact that this one is subtitled “an Alpine Symphony” makes it even more appealing for me—as does the fact that the original orchestral score is part of the film’s restoration. And (spoilers alert) I was very, very happy with my choice.

Im Kampf mit dem Berge (1921; Ger.; Arnold Fanck)

Two climbers, a man and a woman, ascend towards the Liskamm mountain in the Alps. And that’s all the plot outline you need…

The film announces itself as “An Alpine Symphony in pictures / By Arnold Fanck”. Fanck is aiming high, even before the first image hits the screen. Richard Strauss’s tone poem Eine Alpensinfonie (1915) was still a recent cultural phenomenon in 1921, and quite the most famous work with that title. That, too, is a depiction of the ascent and descent of a mountain, starting at dawn and finishing at nightfall. (Though Strauss also saw it as a philosophical allegory of man’s post-Christian moral evolution, planning initially to call the work “Der Antichrist”, after Nietzsche.) Fanck’s film is likewise both a literal depiction of an ascent and a rumination on the power of nature. Like Strauss’s tone poem, Fanck’s film is divided into movements (six “Acts”) and has its own score, by Paul Hindemith (of which, more later).

Many silent films begin by introducing us to its cast via close-ups and written credits. Fanck does the equivalent for mountains (“The Giants of Zermatt”). Each is given an introductory title (i.e. “Weisshorn 4511m” / “Breithorn 4171m” etc), followed by a majestic shot of the peak. It’s a brilliant series of shots, each one carefully framed (sometimes with masking), with clouds and mist speeding by the summits. The music swells and thunders in conjunction with the images, articulating in sound the sense of visual threat, of material might. The mountain at the heart of the film is the last to be named: “Liskamm, called the ‘devourer of men’, 4538m”. Yes, here is the star of our film.

Such is the film’s relative interest in humans and mountains that the only two characters in the film go unnamed, and are merely introduced with a shared introductory title (“Players: Hannes Schneider, Ilse Rohde”). Indeed, the humans are never once given a close-up in the whole film: Fanck is interested in them only as a means to construct his “symphony in pictures” of the mountains. They provide us with a narrative and (at various intervals) a means to reflect on the process of filmmaking on location.

Perhaps this is why the “dialogue” (such as it is) is so perfunctory. I say perfunctory, it’s actually very lengthy—but it’s a kind of narrative guide more than a real conversation. The first such title sets the tone: “I’m going to the Betemps Hut. Do you see over there at the foot of Monte Rosa? I’m staying there by myself. No-one comes up here so late in the Autumn. One shouldn’t go climbing in the mountains alone. It is too dangerous. But it is beautiful.” He’s clearly not trying to chat her up. As if to confirm this, his follow-up is: “There, through this wild glacier full of crevasses, the path leads up to the Liskamm. There one looks down from a height of more than 4000m into Italy. Would you like to come with me up to such heights? But the air is thin up there.” See what I mean? It’s not exactly flirtatious. He then invites her to join him in the morning for the trek, following it up with an intertitle so long that it has to scroll down the text to fit it all in a single screen: “Do you see how the Liskamm is smoking? The Föhn wind is blowing over from Italy. I’m afraid it will be a stormy passage tomorrow morning. The Ice Giant isn’t as harmless as it looks. Many who have encroached upon its giant crevasses and icy walls have never returned. Thus Liskamm is known as the devourer of men. The ascent of Liskamm is attained more infrequently than all the other mountains in this area.” Just as Fanck shows the visual “conversation” between the two climbers in a single shot, so the textual “conversation” is really just a monologue. The film has no interest in either figure as a character, and Fanck offers no attempt at a visual dynamic between them: this scene has no close-ups, indeed no cutting at all.

So what is the film interested in? The scenery. My god, yes, the scenery. I’m not sure how much more I can say about the film’s narrative, save for the fact that its imagery is unendingly mesmerizing. I could easily have taken a capture of every single shot of this film. From the moment the journey starts, the screen is filled with wonderful, striking images. The woman traverses a glacier to reach the hut, and we see the expanse of undulating snow and ice with the dark mountain flanks growing in the background. Daylight is a glowing, golden yellow tint. That evening, we see their destination glowering red. When they set off together, the moonlight makes the world turquoise.

Given that the views are entirely dominated by ice and snow (i.e. white) and rock (i.e. black), it’s worth reflecting on why the entire film is tinted and toned this way. In the first instance, there is a practical advantage in colouring monochrome images: in the context of endless white vistas, tinting reveals subtle nuances in tone that the eye might miss in pure black-and-white. (Fanck’s later films would overcome this partly by being shot on more sensitive filmstock.) Then there is the need to demonstrate the passage of the day, which has a narrative purpose (the added drama of the climbers having to spend a night in the mountains). But the main reason is, I think, more poetic than practical. A film that calls itself an “alpine symphony” clearly has ambitions beyond documentation: Fanck wants to show what it feels like to climb a mountain. The film’s titles move between very practical explanations of what we are being shown (placenames, altitudes, technical equipment) and evocative descriptions. Thus, when the climbers set off the title introduces the sequence: “The shine of the alpine moonlight lies magical and unreal over the frozen world of the eternal ice.” Even the titles are tinted green: typical of many German films of the period, but also integrating Fanck’s text into the coloured world of the film.

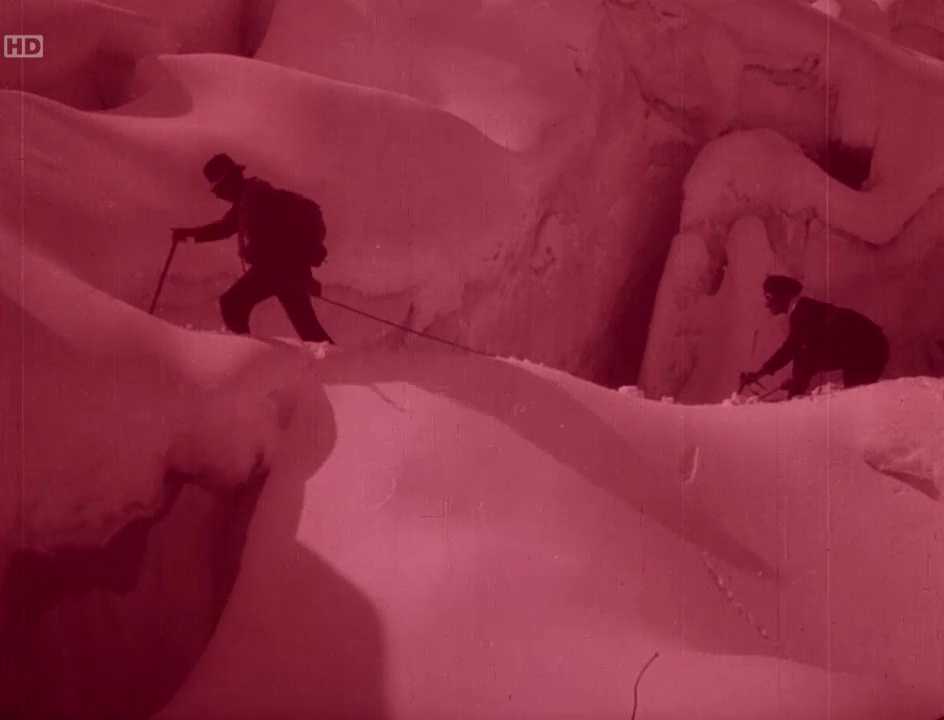

So, we watch the climbers negotiate the fissures and rock, wending slowly across the screen, shot-by-shot up the mountain. Sometimes Fanck lets the whole manoeuvre unfold in a single, unadulterated shot. Other times, he will subtly remove a section from the middle of a scene to speed up the climbers’ progress. It’s an utterly absorbing process. Not only the danger and daring of the climbers, but the means of their climb is fascinating. It’s extraordinary how little equipment they have: just some goggles, a length of rope, spiked boots, and an ice pick that doubles as a walking stick. Much of the time they aren’t wearing gloves, and one can only marvel at the hardiness (and leatheriness) of these mountainfolk. (It’s only when the storm descends late in the film that anyone even bothers to put on a scarf.)

What are we watching? Is this a documentary? Is it fiction? The question seems to be raised by Fanck, too. For although he creates a kind of dramatic narrative, he is also interested in the process of filming what we are watching. About halfway through the film, we suddenly see a man lugging a camera and tripod on his shoulder. He climbs an icy peak, sets up the camera, and begins turning. Fanck’s own camera pans right to show what the camera is filming. It’s such a strange, delightful moment to step out of the fictional world—only to realize that the camera is itself part of that world. You realize that we are seeing one scene of precarious filming via a second scene of precarious filming. Fanck makes us realize the difficulties of filming the very scenes we are watching. (According to his own account, Sepp Allgeier was exhausted after three days of carrying his camera up the mountain. Perhaps it’s not surprising that he wanted some record of their collective exertions within the film itself.) A title then announces: “Shadow play in a crevasse” and we see the silhouette of cameraman and climbers united within the same frame. The shadows of the climbers wave for our benefit (or is it for the cameraman?). I’m still unsure quite what to make of the scene, other than to say Fanck clearly liked the image and thought “why not, I’ll include it in the film”. It turns the film into a meditation on its own making, and (I think) very effectively makes us even more impressed by the logistics of what we see. The very next scene involves the climbers hacking steps into the ice up the side of a frozen cliff face: every metre must be carved to traverse it. And thanks to the previous scenes, we immediately think of the difficulty of carrying two cameras up the same path—and of trying to film the process while suspended over an abyss.

Soon, we are offered extraordinary views of cloud-filled valleys and gleaming peaks. The figures become Caspar-David Friedrich’s “wanderer above a sea of fog”, only the tangible danger of the setting makes the image even more compelling. It’s both romantic vision and practical achievement: tiny figures stand in the thrilling, terrifying context of nature. It’s the real world and it’s sublime.

On the descent, Fanck is (or tries to be) dramatic by showing one of the climbers fall into a crevasse. But it’s done in a single take, in a long shot, and the drama is only achieved by an explanatory intertitle. It’s actually difficult to tell whether anything untoward has actually happened, or if it’s been staged for the camera. It’s less impressive than the very real leaps we see both figures make across ravines, and the extraordinary ascents and descents along sheer cliffs of frozen rock. Similarly, when the storm comes and the two climbers are forced to spend the night in a small rocky ledge, it’s not very dramatic. Even if it’s real, Fanck does not have the interest (or the filmmaking ability) to make the scene more troubling, thrilling, frightening, or even comic. The camera simply records their actions in a single take, with titles doing the rest of the work. It’s difficult not to see such scenes in the light of his later—explicitly fictional—work, where the personal drama of his characters is forced to become more complex, even if on the basic level of more complex (which is to say, any) editing.

Where Fanck does try to ramp things up is in the descriptive titles. Thus, when they descend we are told: “In the last rays of the sinking sun the pair are locked in a struggle with the terrible wall of ice which they must conquer before nightfall.” And then we are asked to view the surrounding shots of the landscape with a poetic sensibility: “Shadows of storm-driven clouds flit like ghosts through the nightmarish Labyrinth of jagged ice walls and dark, gaping fissures.” When the climber falls, we are told that “only the rope saves them from certain doom in the dark abyss of the eternal ice.” And at night, the world beyond the ledge is described through words before being shown through images: “Above them the Föhn roars over the icy peak and whips the endless masses of clouds normally encamped like a lurking monster over Italy, over the mountain tops. Woe betide the mountaineer who is caught by this storm high up on the exposed ridge.”

What also makes the film more dramatic, more poetic, more evocative is the music. The score—for chamber orchestra, augmented by piano (and, I think, harmonium)—is by no less a personage than Paul Hindemith. I admit that Hindemith is not normally my cup of tea, but this is a delightful score. It’s got a small set of melodic themes, not leitmotifs, exactly (the film’s dramatic structure and characterization are not developed enough for a truly integrated musical design), but variations that come and go according to the overall mood of the scenes. What’s delightful about the way it functions is the freedom Fanck’s images give the composer. This isn’t a feature fiction film, it’s an “alpine symphony in images”. The music is thus detached from the images; or, at least, the music is not obliged to follow an intricate series of narrative happenings on screen. Scenes of climbers slowly traversing a landscape, of equipment being tested, of passing of clouds—these are not quite “events” in the usual, dramatic sense. So the music moves like a weather system over the images: floating above them, sometimes innocuous, sometimes playful, sometimes threatening. The musical texture builds, thickens into a storm of sound; then ebbs away, thinning until the images are left to carry the heft of the drama on their own merit. The fact that the music of this “alpine symphony in pictures” is on an entirely different scale to Strauss’s purely musical “alpine symphony” is to its great advantage. Unlike Strauss, Hindemith doesn’t have to bombard the cinemagoer with sonic torrents; he can suggest them, carrying enough weight of sound to make an impact at the right moments (the opening titles, the sights of mountains, the scenes of genuine danger) while at other times pulling back to sparse textures that are more like a hum, a distant sound carried on the breeze. (In these moments, I treasure his use of the harmonium; it’s like a kind of musical wheeze, a squeeze of sound blown through an alpine fissure.)

In the final act of the film, the climbers descend successfully, of course, and then bid goodbye with a disarming casualness. (Again, Fanck’s later work would go all-out to provide more dramatic pay-offs to the same basic plot devices of climbing and descending a mountain.) But then the film ends with an astonishing series of images, preceded by an equally extraordinary title: “And the clouds surge around the lonely summit of the Matterhorn, from time immemorial onwards into gloomy infinities, until someday its giant body is gnawed and corroded by ice, cold, and storm and it falls into ruins.” Fanck hurls us forward in time to the disintegration of the very rock on which he stands to film the scenes. He also speeds forward through time on screen: the clouds surge in time-lapse photography, washing and breaking like waves around the peak, until finally the mountain seems to wrap itself in a shroud and disappear. THE END.

This is a tremendously good film. The photography is exceptional, the pace never hurried. We follow the progress of the climb with an appropriately measured tread. The music is superb, floating across the visual landscapes in a way that enhances the images without ever trying to outdo them. I also think the lack of characterization is one of the film’s strengths. In Fanck’s later films (I think especially of Der Heilige Berg, 1926), we get characters who are sometimes more symbolic than real, or else so banal they might as well be cardboard cut-outs. At either extreme, they occupy so much screen time that their symbolism or their banality becomes wearying. But with Im Kampf mit dem Berge, we never have to take the climbers as anything more than climbers. There is a pleasing matter-of-factness that allows the viewer to become entirely absorbed in the procession of images, in the depth and richness of the screen landscapes. Frankly, I’m happy that the stars of this film are the mountains. There is a scene right at the end of Act V, and the start of Act VI, after the climbers spend the night on the mountain, where we watch the morning sun slowly spread over the mountainside. It’s time traversing an unpopulated world; unpopulated save for the camera, that is. The music creeps into life, building from the wheeze and rumble of harmonium and piano up to the bright blaring of brass. It happens so slowly, and with so little regard for any sense of human life: it’s slow time, deep time, caught on camera. It’s simply fabulous. When everything looks—and sounds—this good, I can do without characters entirely.

Paul Cuff

One thought on “Im Kampf mit dem Berge (1921; Ger.; Arnold Fanck)”