In 1924, a London-based lawyer called Himanshu Rai travelled to Munich. He had founded the Great Eastern Film Corporation and was hoping to join forces with European partners to make films inspired by tales from world religions. Rai met two brothers: Franz and Peter Osten, who together ran the firm Müncher Lichtspielkunst AG (Emelka). Rai and his Indian collaborators—scriptwriter Niranjan Pal and designer Devika Chaudhry—joined forces with the Ostens and their technicians and left for India. In 1925 they made Prem Sanya/The Light of Asia (1925), shot entirely in India using an entirely Indian cast. Its success in Europe encouraged Rai and Osten to team-up again, this time bringing in the support of the UK company British Instructional Films (BIF). BIF started life producing non-fiction films but by the mid-1920s they had begun making features: dramatic recreations of battles of the Great War. But the project they embarked on in 1927-28 was hoped to have a wider appeal. Described as “A Romance of India”, with a screenplay by William A. Burton based on a play by Pal, this film would again be shot in India with an all-Indian cast. Filming took place in and around Agra, with the Maharajah of Jaipur permitting the production to use the historic Mughal palaces as their setting. Set in the early seventeenth-century, the story offered ample opportunity to show-off the settings, costumes, and lore of historic India…

Shiraz: A Romance of India (1928; Ger./In./UK; Franz Osten)

I will let you know the whole story, since it retells the inspiration behind one of India’s most famous landmarks: the Taj Mahal. In Pal’s partially fictionalized version, the child princess Selima is found amid the wreckage of an ambush. Taken home by a potter, she is adopted and raised by his family. The adult Selima (Enakshi Rama Rau) becomes the object of infatuation of the potter’s son Shiraz (Himansu Rai). But she is spotted and kidnapped by a gang of slavers and eventually bought by an agent of Prince Khurram (Charu Roy). Shiraz finds his way to the city where Selima is now part of the Prince’s household, but is unable to intervene as she and the Prince fall in love. This in turn frustrates Dalia (Seeta Devi), a general’s daughter who had hoped to marry the Prince. With the help of her maidservant (Maya Devi), she forges a pass to let Shiraz into the palace—where he is caught with Selima. The Prince orders his execution “under the elephant’s foot” (yes, literally) but when he learns the truth of Dalia’s scheme—culminating in the poisoning of her maid to leave no trail of evidence—he lets Shiraz go. Selima’s true identity is discovered and—since she has royal blood—the Prince is now free to marry her. Eighteen years pass, and Shiraz—now blind—helplessly pines for Selima. When the latter dies and the Prince commissions a design for a monument in her memory, Shriaz’s model is chosen. The two men build the Taj Mahal. THE END.

Well, so much for the story. Being more a kind of extended fable, the characterization is not the most complex imaginable. So, what of the performers?

Let me start by saying that the least appealing aspect of this film is Himansu Rai’s performance. It’s as ineffectual as his character is weak and mopey. There’s no depth or intensity visible in his performance. He doesn’t move expressively, either with his body or with his face. He occasionally holds out his hands or stands still or drops his head a little. And it’s not as if he is restrained in the sense of naturalistic performance. He’s just giving us the basic markers of emotion: but not emotion itself.

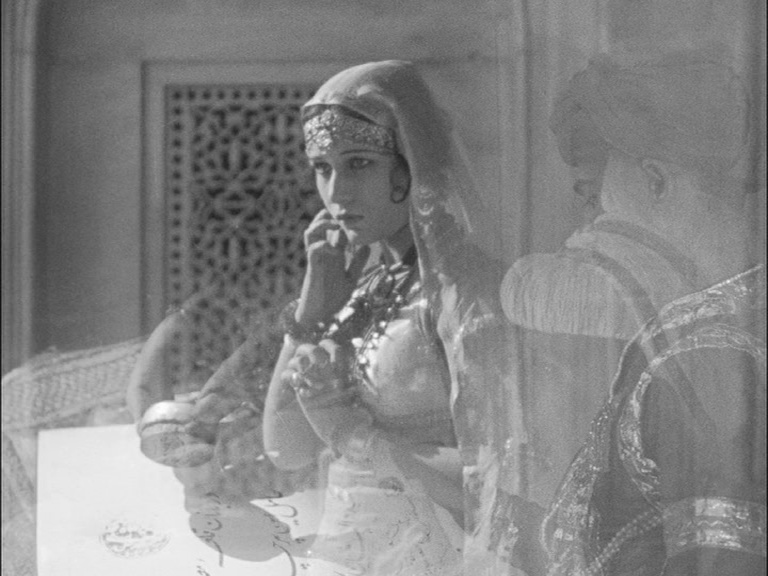

Nor did I particularly like Enakshi Rama Rau as Selima. I wonder if this is in part because of the story and the limitations of how the screenplay deals with the cultural politics (I’ll come to this later). As the film never really challenges any of the authorities or institutions, what can Selima do but be demure and wait for external intervention to aid her? But even within this context, Rau’s performance doesn’t offer great range or expressivity. I think Osten’s direction must surely contribute to this. We get glimpses of Rau’s gorgeous eyes, but she spends so much of the film looking down, looking away, covering herself with a veil, that we never get to linger on her face and see her emotions.

This is not the case with Seeta Devi, whose performance as the scheming Dalia is by far the most engaging in the film. You can read the thoughts pass across her face, the emotions light up her eyes. The camera knows what to do with her, too: it gives us plenty of closer shots to show her expressions, her gestures of impatience, seduction, desire, anger. Devi is absolutely magnetic: not merely beautiful, but agile and demonstrative—she’s truly communicative on screen. It’s noteworthy that the film’s titular hero is not used as the face for the BFI’s poster, nor still the film’s leading lady. Instead, it is Seeta Devi who takes centre stage, and anyone looking at the re-release posters or the Blu-ray box would think that she plays the character called Shiraz. Devi was Anglo-Indian, born Renee Smith, and I noted when watching the film that she’s one of the few people on screen who I could lipread speaking English. Doing a little digging online (weirdly enough, on her French Wikipedia page), I find that Devi spoke neither Hindi nor Bengali—and that this was one of the reasons her career in India petered out swiftly after the arrival of sound.

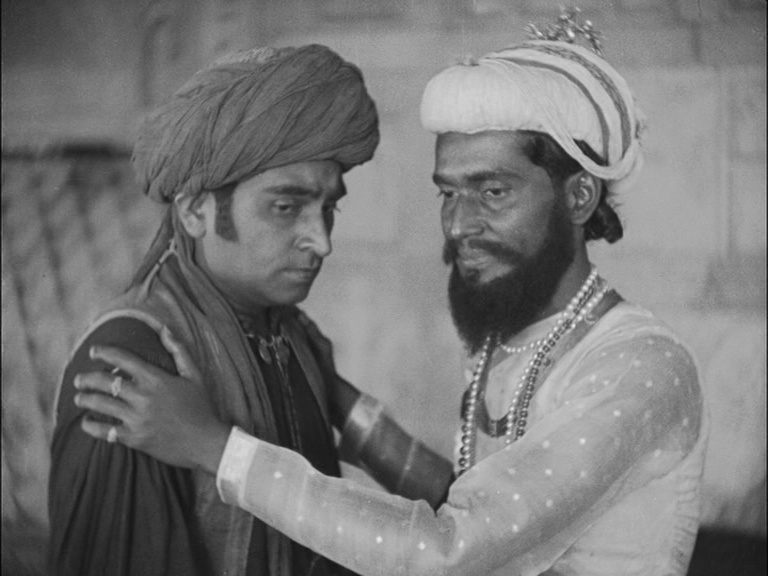

As Prince Khurram, I found myself increasingly drawn in by the performance of Charu Roy. He is understated but in a much more successful way than with Rai or Rau. Roy has a great natural warmth on screen, and he radiates a quiet authority and sense of calm. His is not the most complex of characters (none of them are, to be fair) but he gives a very clear sense of personality, of status, of purpose. I wish Himansu Rai had even a tenth of Charu Roy’s on-screen warmth. Even the minor characters—the Prince’s chief guard, Dalia’s servant—are more expressive, memorable, convincing, than him.

I haven’t said anything much about Franz Osten’s direction. For much of the film, I wasn’t really thinking about it. Everything was neat, concise. But everything was dominated by the settings. The first portion of the film is all exteriors: Shiraz’s small village, the arid landscapes around it. Osten lets the setting do the talking, so much so that I felt a sense of detachment from what was going on in in the drama.

Even when we enter the city of Agra and the beautiful palace interiors and exteriors, the very formality of the surroundings dominated the tone of the drama. Everything is very neatly laid out, with plentiful use of shots that look through archways, down avenues, throughs doors and gates.

Only when the intrigue with Dalia got going did I start to be fully engaged. Here at last was a character with a bit more personality, more of a sense of a human being rather than a storybook figure (the poor potter, the abandoned princess, the noble prince). It is her actions that also seem to inspire Osten to be a bit more inventive. When Dalia forges the stamp on the pass for Shiraz, we see her in a mid-shot crouched by the chest with the official stamps. Osten cuts to what appears at first to be a blank screen. A second later, Dalia’s hand (we know it’s her hand because of the number of jewels it bears) appears slowly from left of frame, passing the document to another hand that appears from the right. Cut to a close-up of Shiraz, waiting at the wall to receive the letter. It is silence, I think, that makes the shot of the hands so startling. The transition is purely visual, and although it offers narrative continuity (the document being forged, the document being transported, the document being delivered), visually the out-of-focus background of a white wall is a stark disruption from the last shot of a dark interior space. Without any kind of background sound—even the gentle hiss of an unoccupied soundtrack—the cut to the white space is startling. Later in the film, Dalia’s thought process is shown through superimposition: we see the document again, the hands, the destination, the threat of discovery. All this is indicative of the more dramatic elements of the story: it is Dalia who tries to change events, to rely on her own wit rather than the will of Allah or the whims of the Prince. Thus Osten must make more of her, more of her agency. When she is removed from the film, the remainder of the story once more becomes a rather uninvolving series of pictures.

This brings me to my major reservation about the film. The film deliberately refuses to interrogate the world it shows us, the world whose cultural/political shape it relies on as the basis of its story. If the setting in seventeenth-century India is meant to avoid the awkwardness of contemporary, twentieth-century history (i.e. the British!), then it also creates other kinds of cultural awkwardness. In the first place, we are presumably meant to be as outraged as Shiraz that Selima has been enslaved, but the film never interrogates slavery—it cannot, since the Prince himself is the chief slaveowner of the state and buys Selima as one among many young female slaves. Indeed, Shiraz himself—at the slave market—shouts that Selima should not be sold because she has been kidnapped, not that slavery itself is an outrage. (He offers no opinion on any of the other poor wretches up for sale.) What’s more, when Selima refuses to give herself (i.e. her body) to the Prince, he replies that he has power enough to force her to take what he wants. The threat of rape is glossed over, as is the implication that that’s how the Prince has operated and continues to operate. The film doesn’t seek to find any complexity or trouble with the way this world works, nor do its main characters: Selima isn’t shocked or defensive with this threat, but simply says that whatever else may be taken, her heart cannot. And the Prince still is prepared to use great cruelty: to have the elephant crush Shiraz to death for not explaining himself, then (eighteen years later) to have Shiraz blinded with a spike so he can’t out-do his design for the Taj Mahal. Each time he relents, but clearly he remains prepared to use violence. His goodness is (albeit vaguely) emphasized by others in their descriptions of him (he is liked by his people etc). But he’s a “good” prince who practices slavery and threatens rape, torture, and death. In short, he should be a more ambiguous, complex character than the film is prepared or able to make him.

Neither does the film show interest in interrogating Shiraz’s actions. After all, Shiraz abandons his poor family to chase after Selima; he doesn’t say goodbye, nor does he ever send word to say what happened to him or to her. Nor does the film question why Shiraz turns down the money offered him by the Prince when he proves Selima’s royal status. Might he not send something back to support his family in his home village? Indeed, the film is populated by characters who passively accept what happens to them. Selima herself is lucky enough that she likes her enslaver, who is (when not torturing or enslaving) kind. Only Dalia has any kind of interest in upsetting the status quo, but she herself is prepared to murder her servant to save her own skin. Dalia is the only character apart from the Prince who wants to exert agency, but even she is trapped within the patriarchal order that can dispose of her on a whim. (She is exiled by the Prince, who says he never wants to see her face again; the film duly complies.) The film isn’t interested in challenging any of the systems it depicts, neither the slavery nor the royal autocracy that are essential elements of the world on screen.

The score for the 2017 restoration of Shiraz is by Anoushka Shankar, with a mixture of Indian and western instruments. (The notes also say that the music was arranged and orchestrated by two others, Danny Keane and Julian Hepple, so I’d be curious to know how this was organized. “Arranged and orchestrated by” is a common credit for scores from the 1920s, but for a new score it is much less so.) The music is absolutely sympathetic to the setting, and I enjoyed how it emphasized subtle elements of rhythm on screen without attempting to mimic everything that was happening. That said, the way the music floats over the images increased my sense of detachment from the drama for a good chunk of the film—but this is far more the film’s doing than the score’s. I didn’t even mind the presence of some chanting during the climactic scene with the elephant. Normally, I dislike voices in scores for silent films. And the fact that I took against the Nitin Sawhney score for Osten’s next Indian film, A Throw of Dice (1929), for the very reason that he includes an irritating trope of whispering voices in the soundtrack, means that I was surprised that I wasn’t bothered by the voices in the score for Shiraz. What makes the different is that Sawhney uses voices in a kind of sonic superimposition over the orchestra: it is a sound element that can only exist via the digital manipulation of volume and balance. This struck me as being entirely alien to the period, turning a score that could be performed live and have a life within a cinema into a soundtrack for DVD. This is a silent film, damn it, not a soundtracked one. But the voices in Shiraz are part of the live performance of the score. They sound from within the orchestra, not from an imposed wash of acoustic sound. While not exactly being a “period” score, it doesn’t deliberately emphasize acoustic aspects that could only derive from the present.

I enjoyed Shiraz, more so as it went along. And while I have reservations about some of the performances and the lack of depth in its story, it is nevertheless a very beautiful film to look at. Much of the restoration derives from the original 35mm negative and looks stunning. You’ll struggle to find a sharper-looking print of a film from this era. I makes me want to revisit the other films produced by this Indian-European collaboration. A Throw of Dice is at least on DVD, but Prem Sanya can still only be seen in off-air copies derived from its broadcast on ARTE from 2001. Nevertheless, I promise to seek out and comment in the future…

Paul Cuff

One thought on “Shiraz: A Romance of India (1928; Ger./In./UK; Franz Osten)”