Why did I choose to watch this film? Well, frankly, I was in a bad mood. I started the day in triumphant spirit, having received an unexpectedly early delivery of Dreyer’s Die Gezeichneten (1922). This was the DVD edition produced by ARTE, including a score for the film by Bernd Thewes that I’d never heard. Much to my delight, the back of the box said: “Untertitl: Englisch”. I sat down to enjoy the film. It started. There were no subtitles. I really had been looking forward to seeing (and hearing) Die Gezeichneten, but my German isn’t up to the task of reading the many lengthy titles of this film. After a bleak morning the next day trying and failing to synch up the soundtrack with the video from the DFI Blu-ray release (the intertitles are a different length, the DFI splitting them into multiple titles for the sake of accommodating their dual Danish-English translations), I was in a bad mood. I needed to choose another film to watch. I wanted something angry, bleak. It should be tonally similar to the anticipated grimness of Die Gezeichneten and tonally similar to the irritation of my mood. Hence, Brüder: a film I knew nothing about, other than it seemed moody, bleak, and had a score of equal abrasiveness. Bring it on.

Brüder (1929; Ger.; Werner Hochbaum)

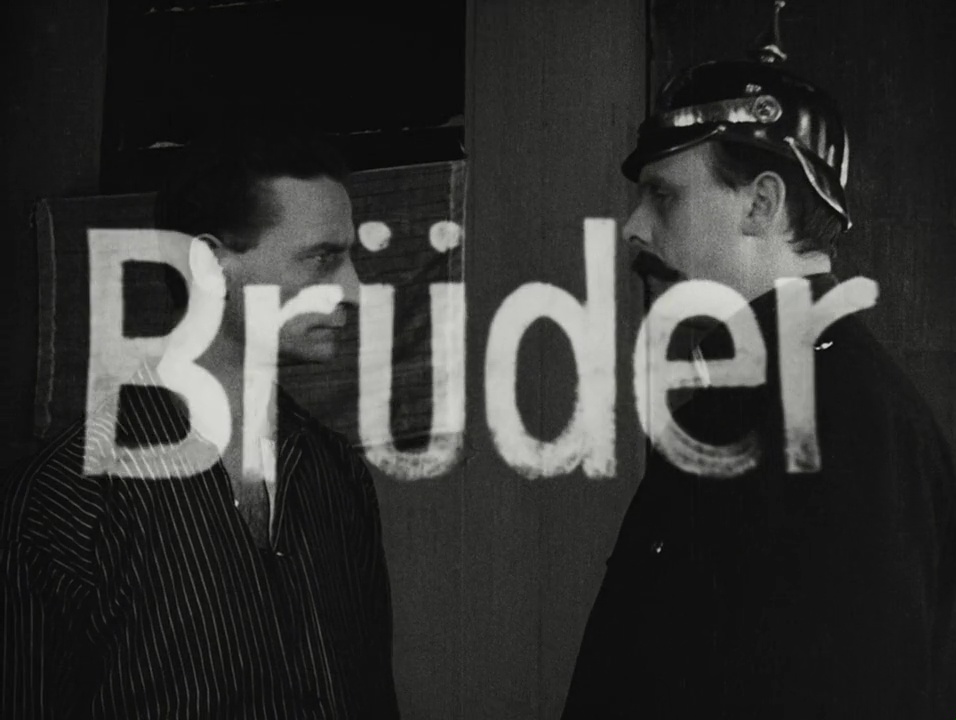

The opening credits are broken up with images—little vignettes in themselves—that foreground the film’s strange tone, it’s blunt and sometimes disjointed editing. “Der Film”—one title announces, before we cut to a shot of two men, one in shirtsleeves, the other in uniform, facing each other. Superimposed in the space between them, the word “Brüder” appears and barges its way forward until it threatens to burst out of the screen. Next, a line of workers, hand in hand, a strike line, stand against a black expanse. They are looking straight at the camera. It’s a weird, intense opening. Then we cut back to more text, and you realize that this is a continuation of the sentence began by “Der Film”, then bridged by the superimposed “Brüder” and subsequent shot: “is based on authentic elements and relates an episode from the dock workers’ strike which took place in Hamburg in 1896-97.” After more credits, a title announces: “This film is an attempt to create, with simple means, a German proletarian film. The performers are dock workers, workers’ wives, children, and other common people. All of whom were appearing in front of a camera for the first time.” The cast list credits no performers, simply listing their roles.

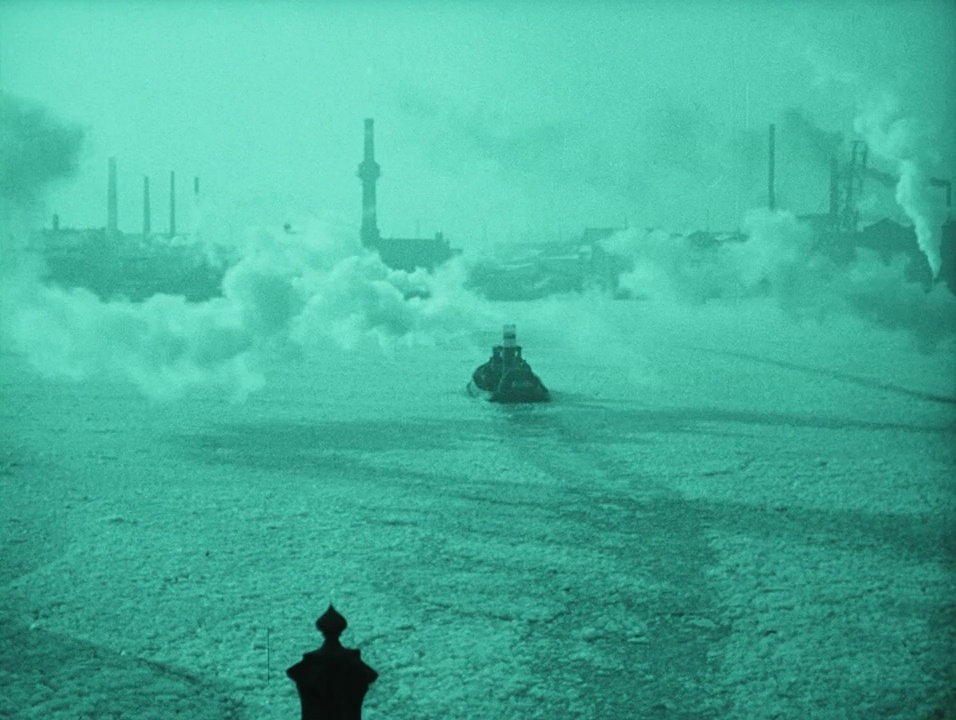

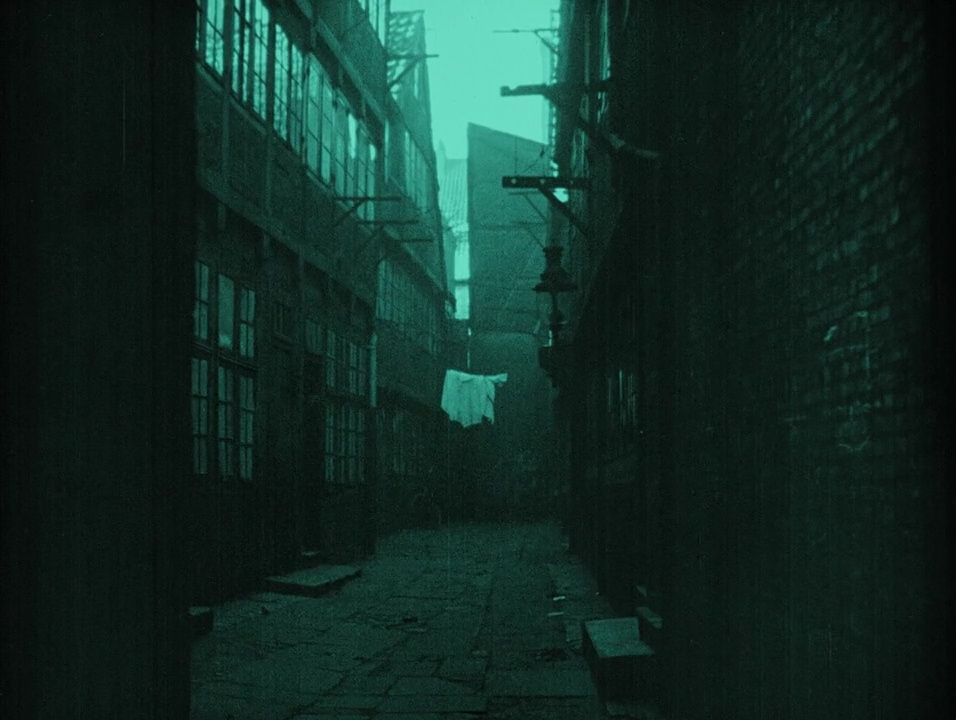

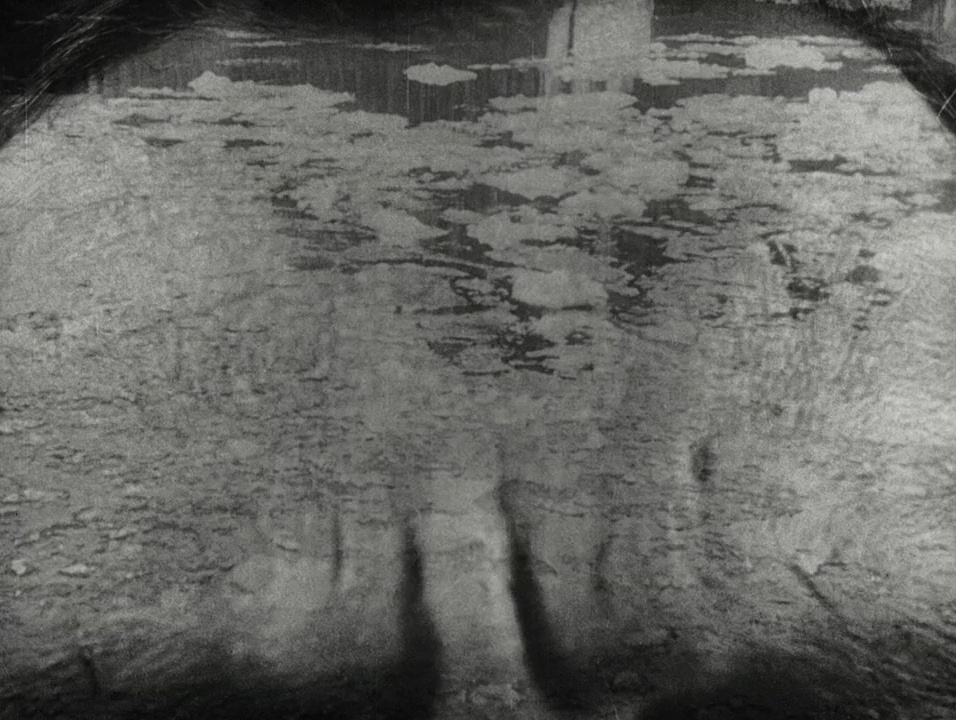

Act 1. “The history of humanity is the history of its class struggles”. (I’m braced!) “On a winter morning in 1896.” Shots of Hamburg harbour. Ice-coated water. Turquoise tinting. Even the glints of sunlight are cold. Dark boats cross the harbour. Clouds of vapour from their stacks. The dockland on the horizon. Industrial chimneys, industrial cranes. Closer shots of the sea, the waves lifting the coating of ice. Strange, viscous ripples on the water’s surface. Gulls, tugs, liners, smoke. The quay. The houses. Rooftops coated in snow. Dark, cramped streets. Nineteenth-century tenements. Washing on the line. Factories. A newspaper drifting down an empty street.

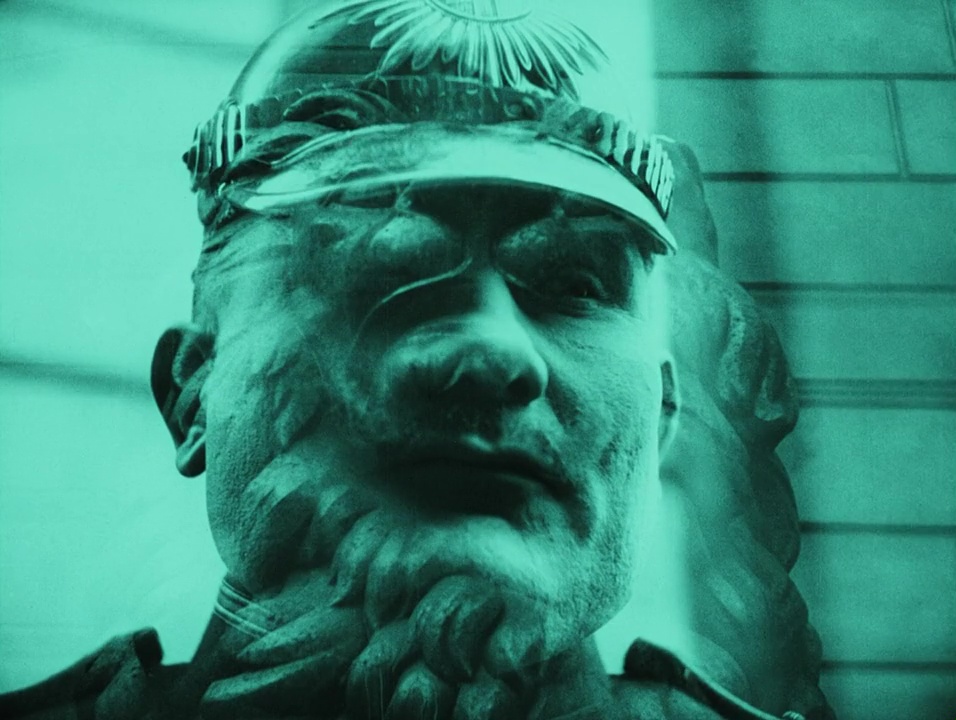

A policeman, conspicuous by the quality of his uniform, the sheen of his spiked helmet. A close-up of his face dissolves slowly onto that of a stone lion. Shots of show-covered monuments to the nation, to the war dead. A statue of Wilhelm II in close-up, the camera tracking back, then panning around the police station; sleeping officers, a tired-looking desk clerk. Nameless men, sleeping in their uniforms; helmets on a cupboard, a sword against the wall.

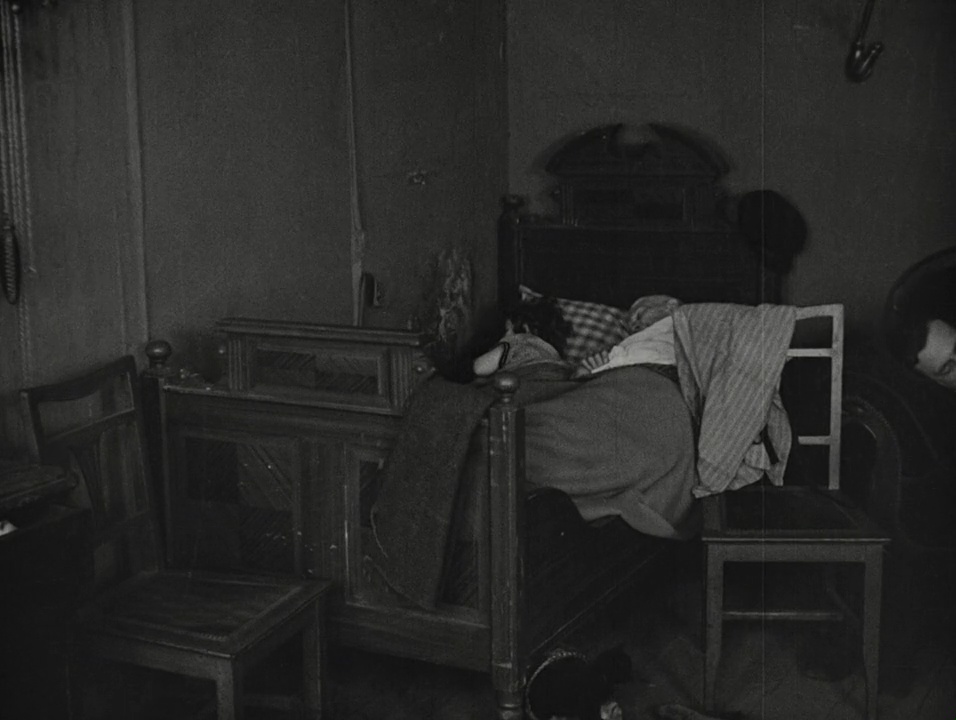

Now cut to another illustration on another wall: an image of liberty urging on a crowd. Another reverse tracking shot, the camera pulling back to reveal the main protagonist’s apartment: The nameless docker sleeps on a sofa, his wife in a single bed, his mother with their child in another single bed. The wife coughs and the camera awkwardly pans down and up the length of her sleeping body: we see the size of the bed, the stiffness of her limbs, the lack of space all around her.

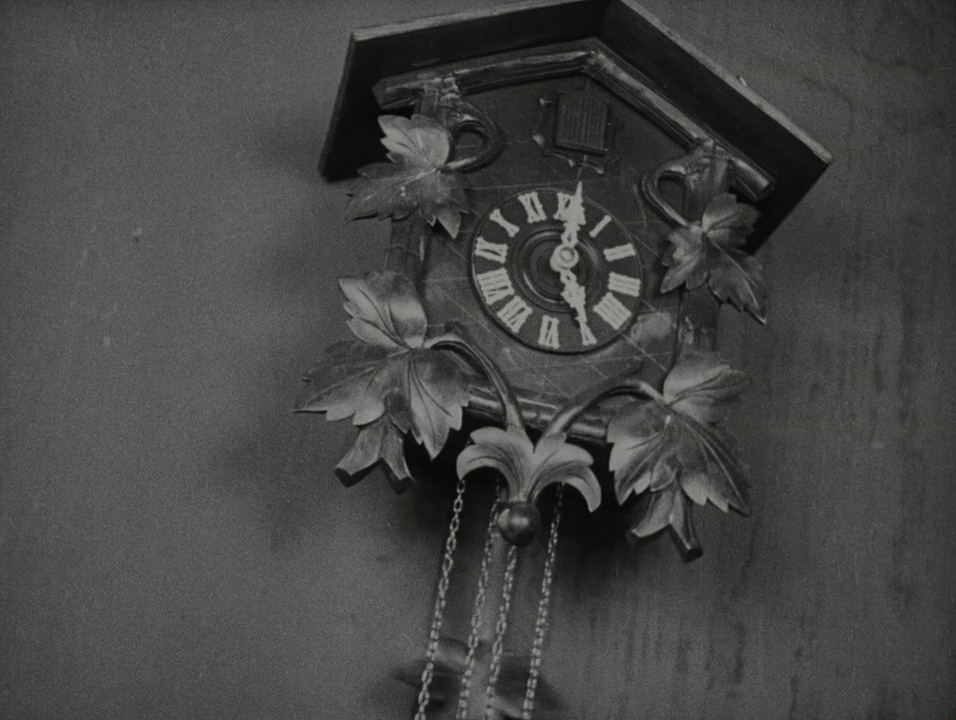

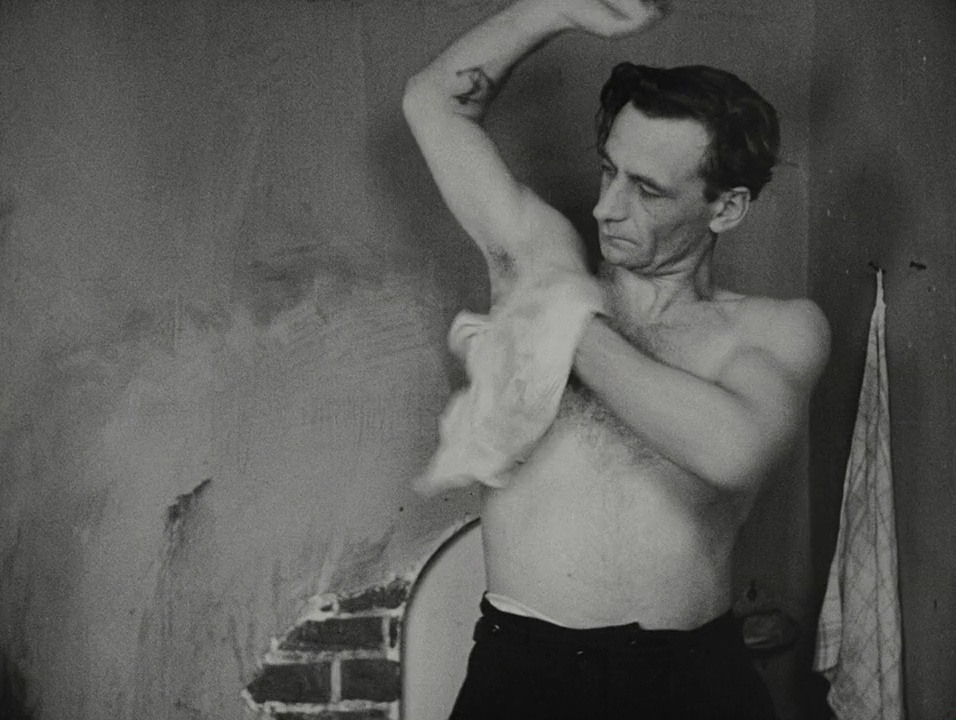

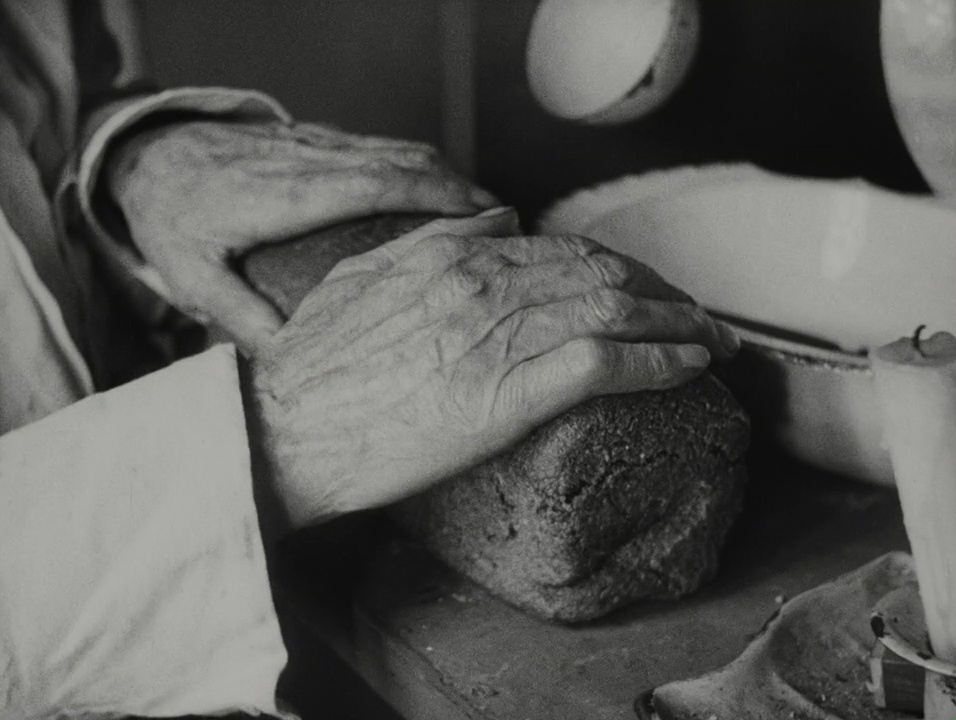

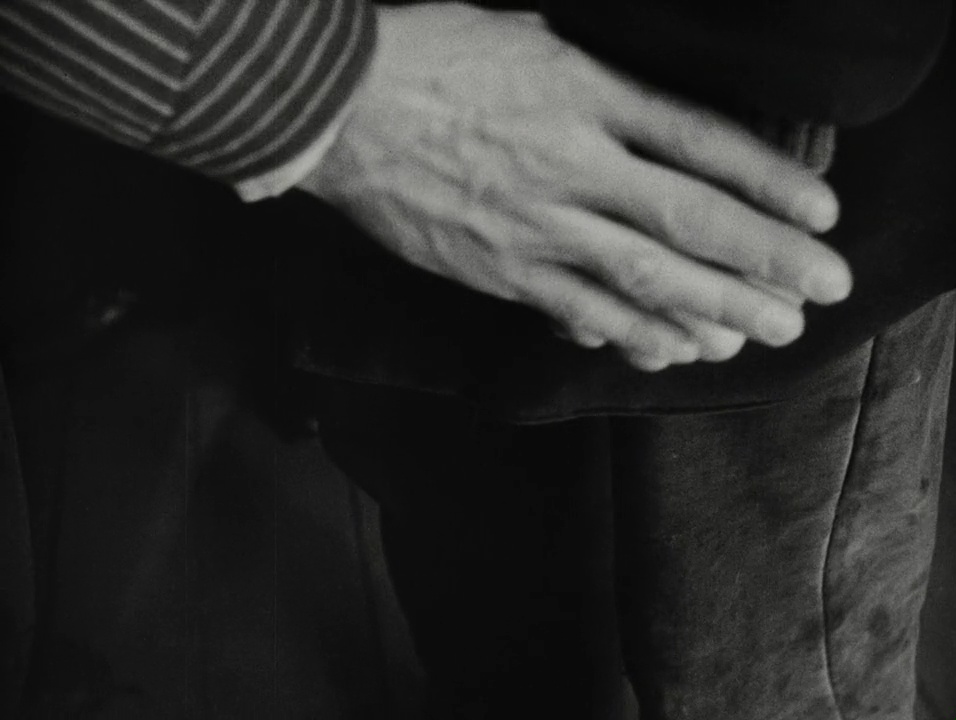

The town clock strikes five in the morning. The clock in the apartment strikes five. The grandmother gets out of bed, puts on her slippers, lights the lamp, goes to the tiny kitchen, lights the stove. The man washes in a sink, towels himself down. In close-up we watch his mother’s ancient hands making the morning coffee, buttering thinly sliced bread. They sit together and eat: one slice of bread each. He sprinkles a pinch of salt on the buttered bread. The camera takes in their breakfast in a single shot: the rationing of the butter, the dividing of the coffee into a flask for him to take to work. Close-ups of their few words; no intertitles. Back to the establishing shot (which establishes only the extremely limited confines of the kitchen table in the corner of the room), a few more unsubtitled words, then he puts on his hat and jacket and heads out into the snow. The mother, wife, and child sit in the main room and eat their slices of bread. The cat laps at a cup. End of Act 1, an “act” that has consisted in the recording of remarkably prosaic details. It’s just everyday life, the morning routine, presented without embellishment. It’s plain, sparse, terse.

Act 2. The docks. Men crowd onto the decks of roofless ferries and are taken across the water to work. The water is black beneath the ice. The smoke is white against the city, black against the sky.

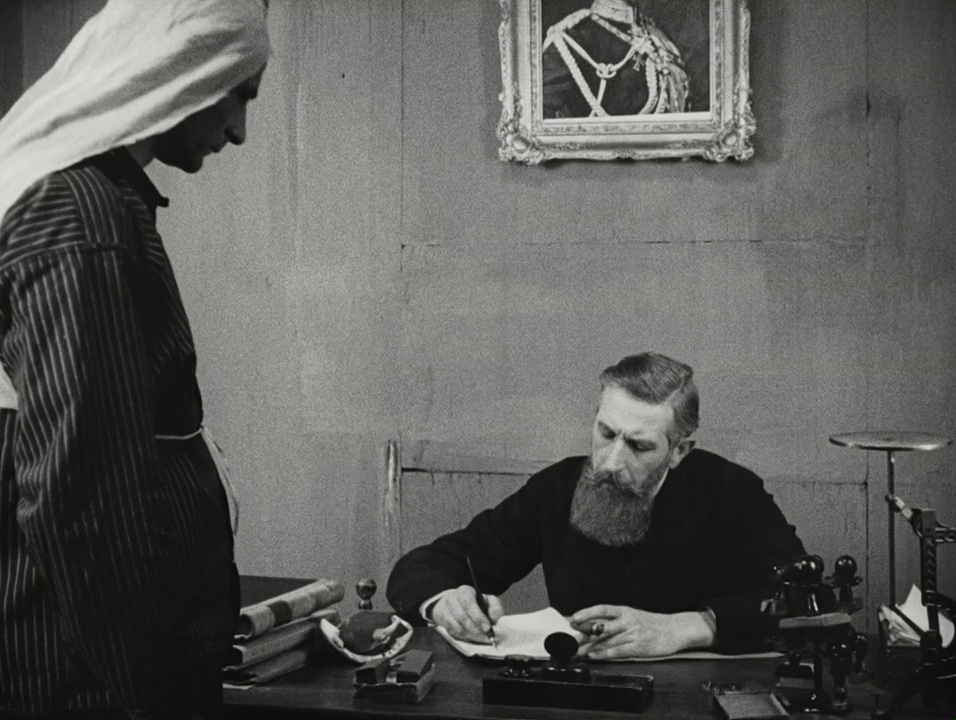

In an office, a clerk bows before the portrait of the Kaiser, then places the day’s papers on a desk and leaves.

Workers unload the cargo from large ships. It’s daylight now, but the although the tinting has gone the monochrome shots of the docks are just as cold. The dockers wear flat caps, or protective sheets to carry the sacks on their heads. The foreman pushes them on. The workers are angry. The docker leads a delegation to demand a pay rise. He speaks bluntly, the film’s titles render his words briefly. A bearded official sits at the desk below the image of the Kaiser. The gilt of its frame, and the painted gilt of the Kaiser’s uniform, are the only glimpses of luxury we see in the film. The pay rise is rejected: the money is to be reinvested, but not in the workforce.

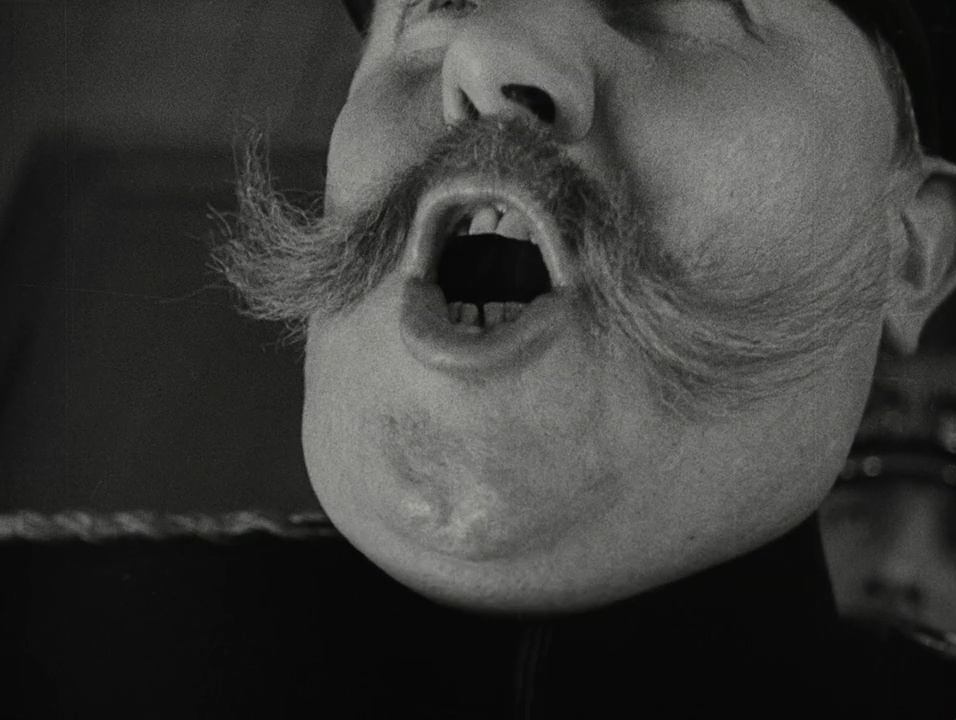

The police station. The camera titles down from the bust of the Kaiser to the moustached face of an officer. His men—including the docker’s brother—look tired. They salute and wearily about-face.

“After 36 hours of toil”: a shift change. The turquoise tinting has returned: it’s the evening, which is indistinguishable from the morning. Weary lines of workers leave the boats, tramp up gangways, over footbridges.

Act 3. The return home. Snowbound streets. Greyish sludge along the narrow paths. Darks lines of indistinguishable tenements. The child on the steps outside the apartment. Her father greets her, goes inside—straight to the kitchen table. A pan of food and a cup of coffee is instantly provided by his mother. The docker eats in silence, alone, wiping his mouth on his sleeve, mopping his brow. But the bread falls from his hand. He falls asleep at his meal.

A line of dockers arrive, ascend to the flat. They sit on what we know is the man’s bed, the only space in the house. Look how Hochbaum frames them: the men gathered around a tiny table, while the wife lies in the neighbouring bed, her face just in frame on the right. Only when the labour leader arrives, and gently taps her on the shoulder as he passes, does anyone acknowledge her presence in the room. (But the camera has noticed: it cannot not but notice, the room is so small.)

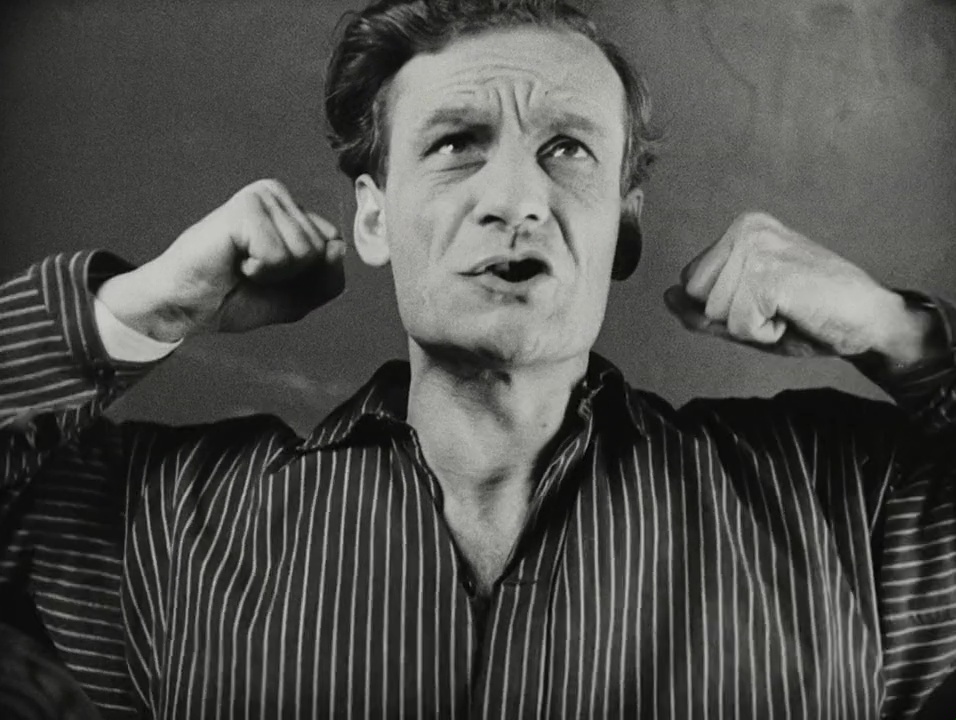

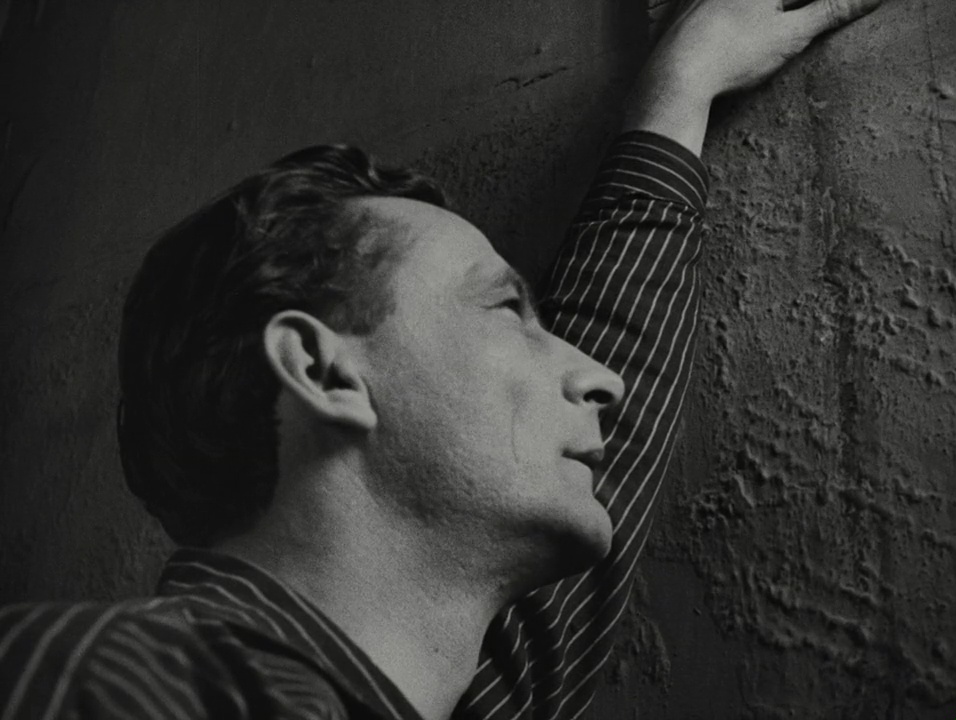

The dockers, at the main protagonist’s urging, agree to strike. Close-ups of his face, from below, earnest, impassioned; of hands clasped. The editing is awkward, unpolished; the shots hold a little too long, or not long enough.

The meeting of the workers. Real faces, working faces. Faces that have known manual labour their whole lives. Close-ups of men speechifying, waving fists. They agree to strike.

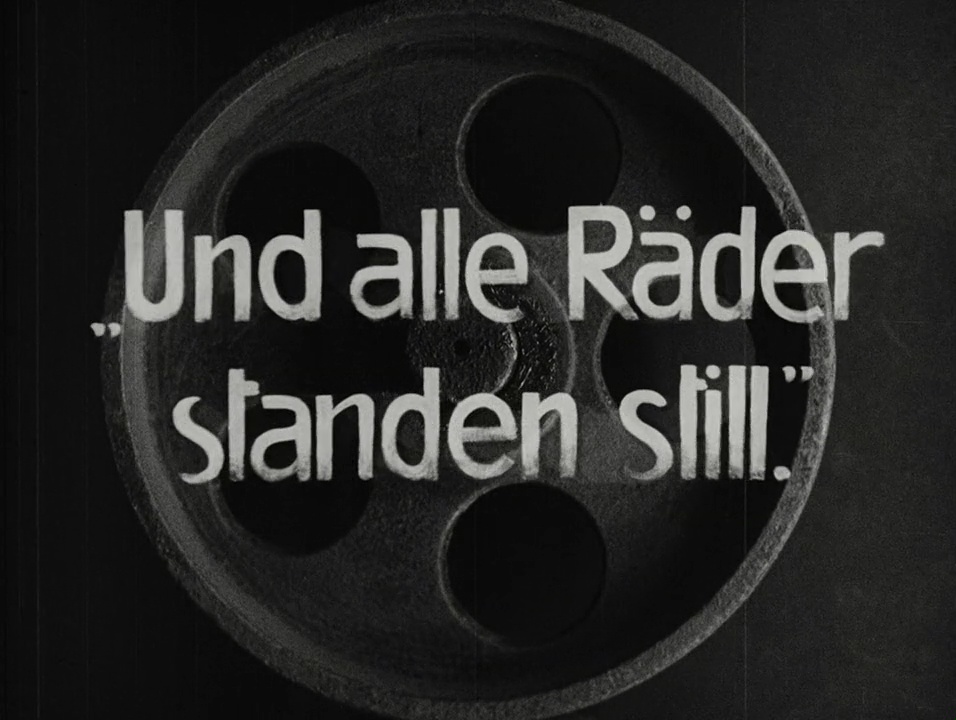

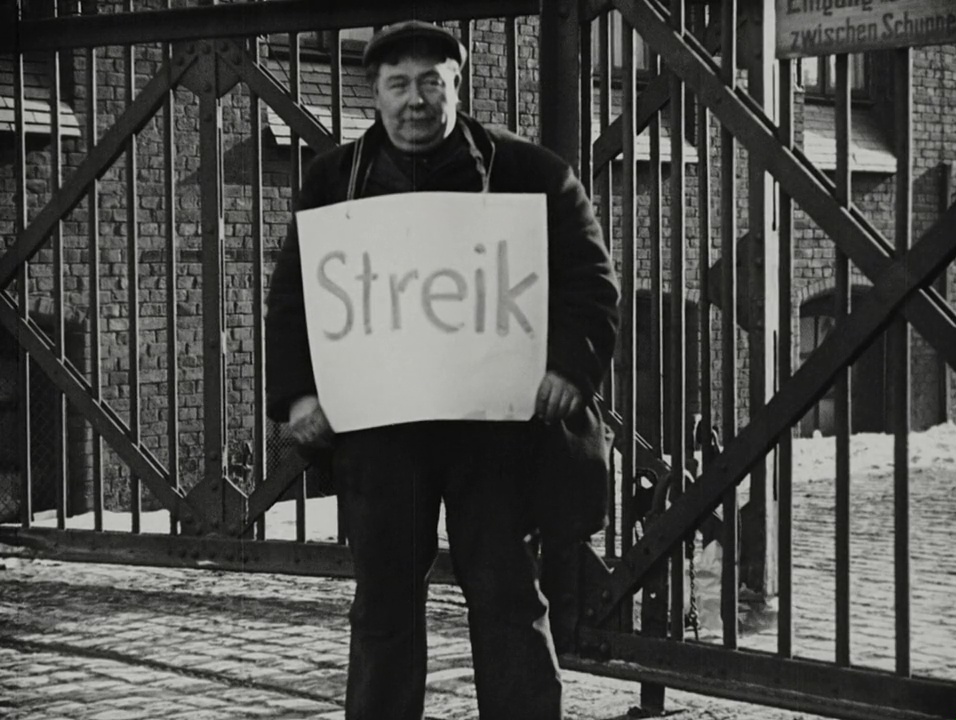

“And all the wheels stood still.” Details of the silent port: ships sat in the tides of ice. Unmoving trains. A man standing at the dockland gates, holding a placard that says: “Strike”. End of Acct 3.

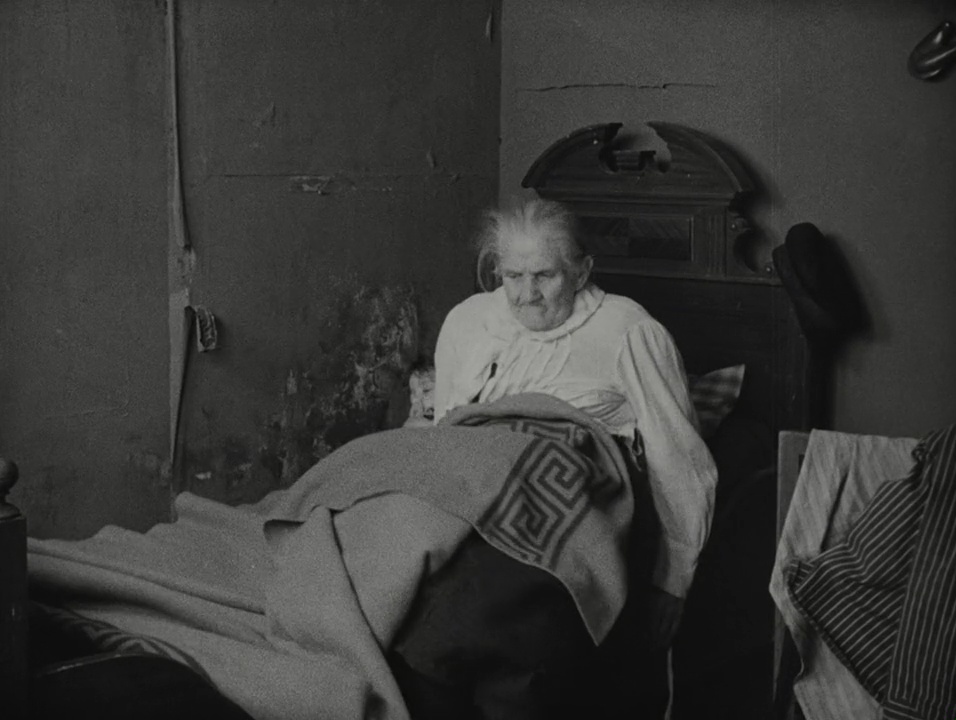

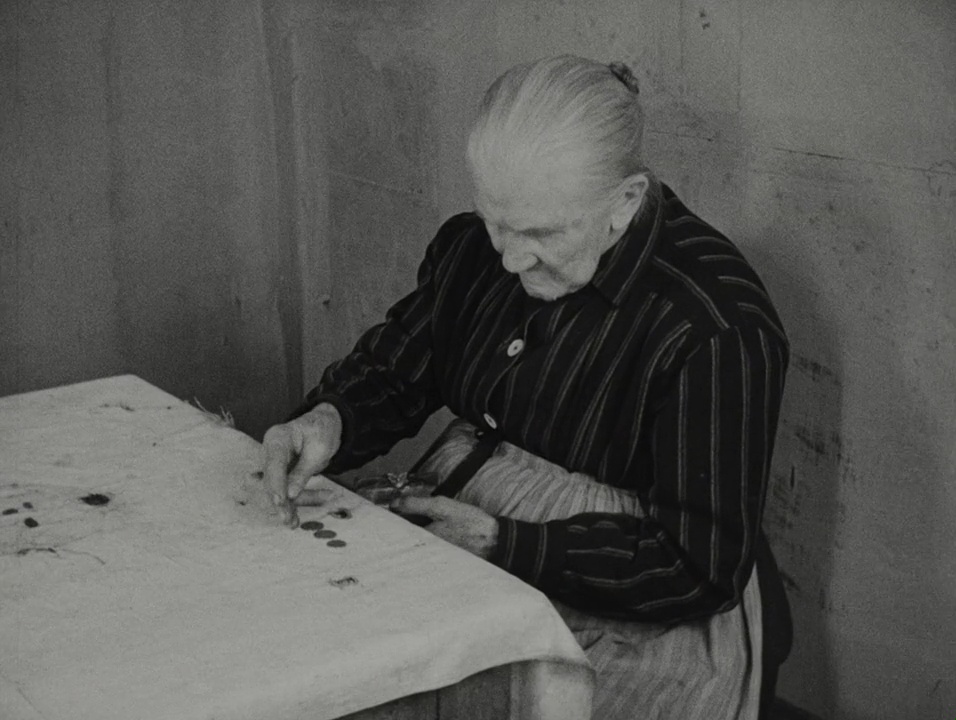

Act 4. The clock strikes five. The docker turns over and goes back to sleep. But his mother still gets up and goes to the kitchen. She gently strokes the loaf of bread. She knows it will have to last now that their income has ceased. It’s a potent image, and one of the ways in which Hochbaum gently complicates the narrative. The men take action, but the women in the household take the consequences.

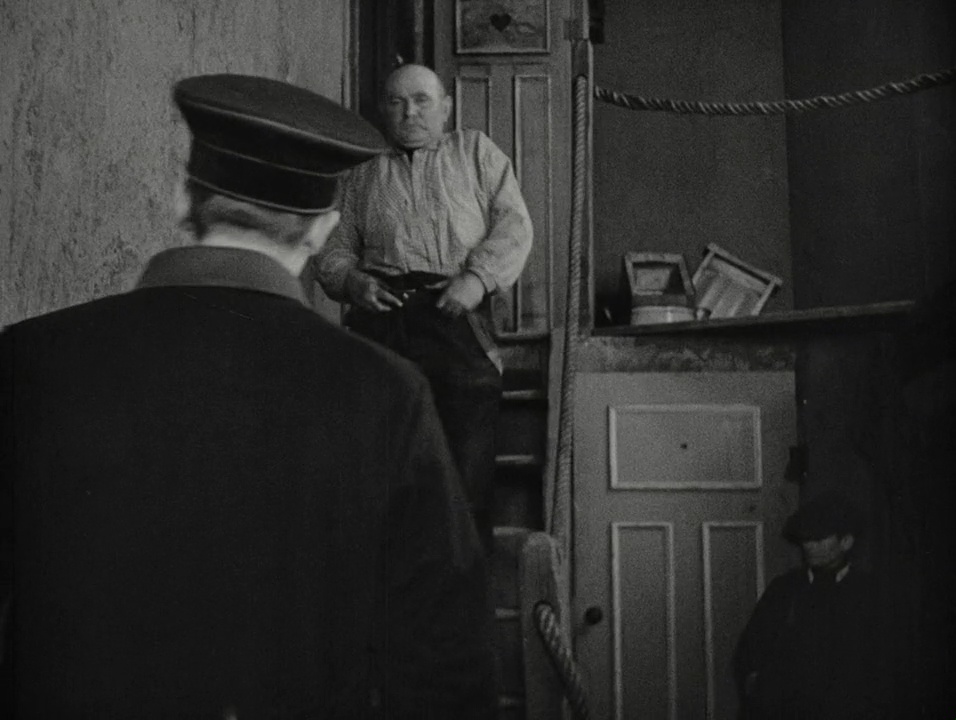

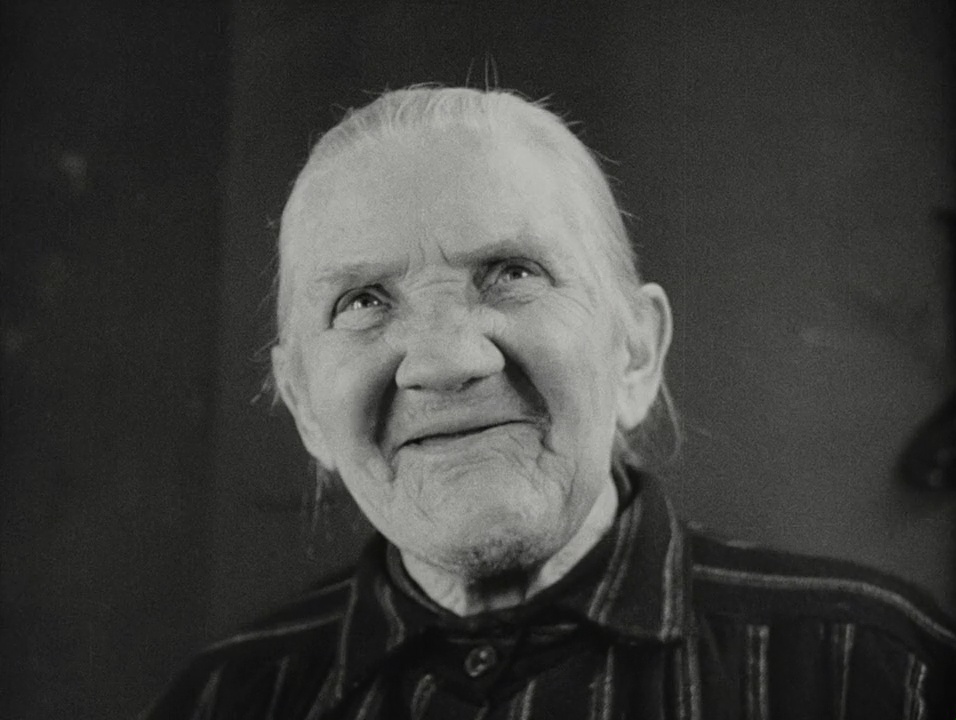

The docker’s brother—the policeman—comes to visit. On the way in, he passes an old man on the stairs, still buttoning up his trousers, who barges the policemen aside. It’s a marker of the brother’s outsider status. (But the scene also reveals what the tiny door is outside the entrance to the docker’s apartment: it’s a toilet shared by the other residents in the block.) It’s the first time we see the family together. The toothless mother smiles and shakes the brother’s hand. “Brother!” he says, stretching out a hand to the docker. Hochbaum shows us the hand extending into the frame, the brother sat moodily in the corner of the sofa—refusing it. When the policeman puts his hat on the table, the docker picks it up and puts it on the floor. The film’s obsession with the significance of uniform is shared by the protagonists. Now the docker’s little girl comes to make friends with her uncle, but she too is manhandled away from the policeman. As he leaves, his hand is again refused by the docker. (But not by his mother, who shakes it, then sits sadly on a seat by the door, head downcast.) Even outside, the policeman is insulted: “Down with the police!”, a child has scrawled on the wall. And the strikers on the street spit in his wake.

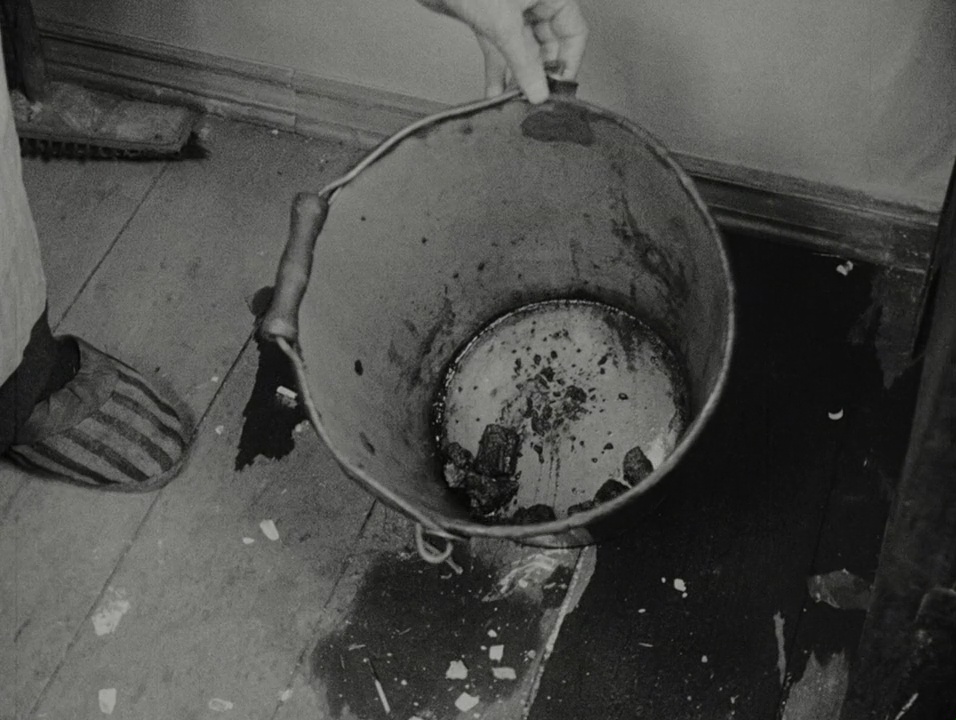

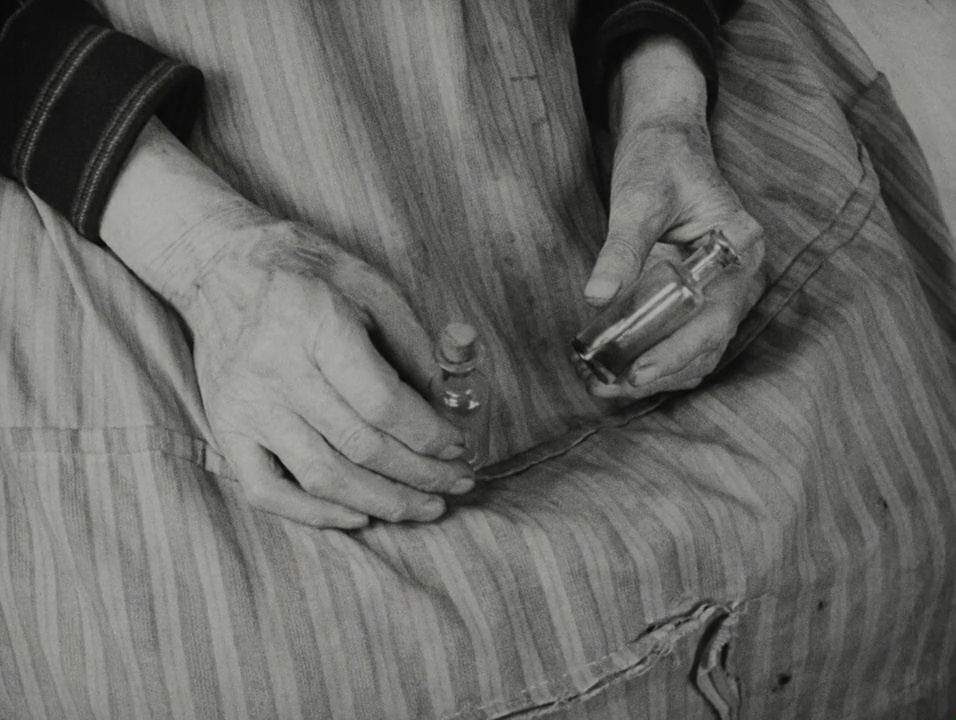

But it’s the next scene that carries more weight. For the mother goes over the household supplies. She looks at the stump of bread, at the few cubes of meat in a metal bucket in the kitchen, at the smear of butter (just lard?) in the pot, at the few pennies left in her purse. She sits alone, a close-up of her ancient hands resting in her lap. The docker’s wife coughs, a thin trickle of blood coming from the corner of her mouth. The mother sits by her bedside and finds two tiny bottles of medicine. They are nearly empty. She puts a few coins next to them, just as she had counted the coins in the kitchen—it’s ostensibly for her calculations, but also for our knowledge. This second showing of money is not the subtlest shot in the film, but the next shots are: we see the mother stroke her daughter-in-law’s hand. It’s one of the only moments of tenderness in the entire film.

The next scenes show more contact, this time violent: strike-breakers accost the dockers at the gates. But the strike is continued. End of Act 4.

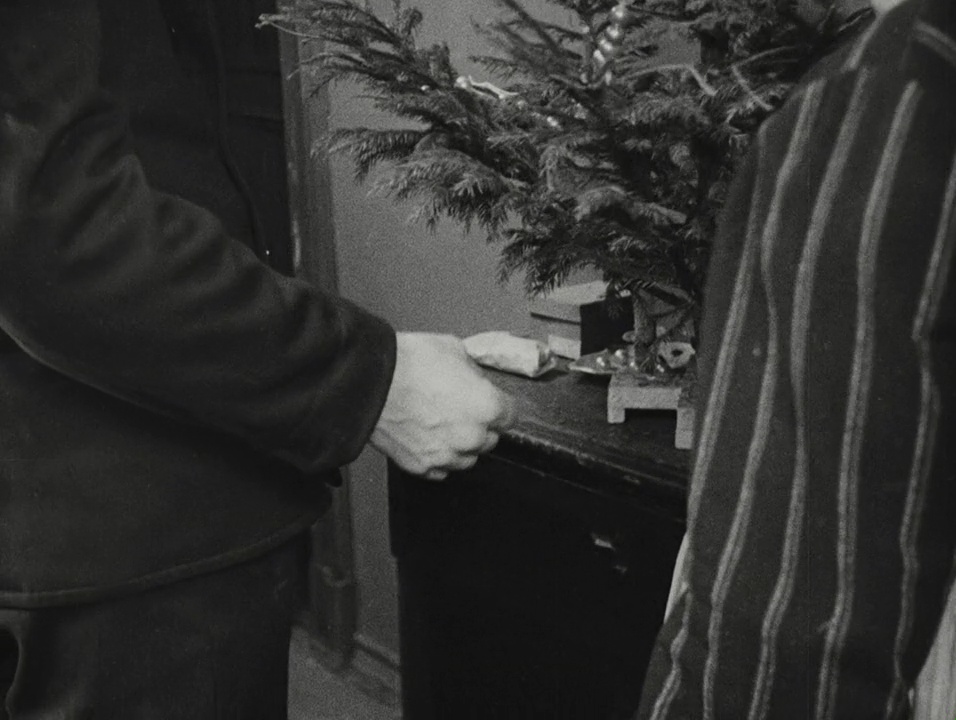

Act 5. Christmas. Shots of snow-covered statues, memorials. The docks still unmoving, the streets still empty. The docker’s mother is putting decorations on a tree. Her granddaughter smiles up at her, and at the little angel she puts on a branch. The tree is small, the decorations sparse. The camera—handheld (for the sake of space, if nothing else)—awkwardly pans around the room. In her sickbed, the wife smiles. The docker returns. He’s about to grab the tree and throw it to the ground, but he sees the look of delight in her daughter’s face and relents.

Christmas dinner is about to be interrupted. The family are eating but the police are on their way. The police come in. There is a struggle. The tree falls to the ground, the angel hurled across the floor. A montage of violent gestures (imperfectly shot, imperfectly edited). The docker tripped, falling, the ceiling swirling, a nail in the wall, his hand flung up, now covered in blood; the wife striking out, being shoved away, dragging herself across the floor; the policeman’s boot crushing the angel, whose banner “Peace on earth” is left pasted to the floor. The old woman hunched on the ground, head down.

At the station, the docker is one of several taken into custody. His brother is left in charge, as a band of dockers sing a protest song outside the station—and the other officers stand guard. “Brothers!, “Freedom!” The words are flung across the screen, part song, part slogan, part though process: for the two brothers stand—per the opening shot of the film—and the docker is ushered out to freedom. As a scuffle breaks out outside the jail, the fifth act ends.

Act 6. Back in his apartment, the leaders of the strike gather. The grandmother leads the little girl into the kitchen and lights the stove. We see her counting the few remaining beans and dutifully grind them.

The docker is thinking, and Hochbaum superimposes a montage of scenes from the film over his brow. But the police are here, and the others protect him. The camera slowly pans down an arm, a hand slowly clenching into a fist. Then the docker’s hand touches his, and the camera pans (again, agonizingly slowly) up his arm to his head: we see him shake his head, then speak: “We are making a mistake and struggle in vain against isolated individuals. Stay true to our ideas, forge a powerful community. Then, time and collective strength will get the better of the system, and the future will be ours.” So he says, speaking the message of the film. He allows himself to be led away and, in a prison cell, his wife visits him and sneaks a newspaper into his hand: the strike is over. The docker looks away.

Cut to a flag, the shot tinted red, rising, followed by more text: “On February 8, 1897, the central strike committee published an appeal that ended with a prophetic look in the direction of the future: This eleven-week struggle cost harm and sacrifices of all kinds. It was necessary! Thousands and thousands of spirits that had been asleep until then, the souls of thousands and thousands of women, and maturing youths have been, during these weeks, set ablaze by the spark of enthusiasm.” Iris-in on the red flag. ENDE

Hmm. Well, this film is a decidedly mixed bag. The shots of the docklands are superb: all the atmosphere of place and time are there; the ice-covered waters, the snow-covered streets; the dark tenements, the blank skies, the smoke and dirt. I could have watched a montage of these documentary shots for a long time, so rich and deep was the photography and so starkly beautiful were the images. But even if the photography is excellent, the film as a whole is uneven and often bordering on amateurish. Whenever the camera tracks or pans, it is so slow as to be awkward: and the more meaning the director wishes to convey, the more the effort involved undoes any effect the shots might have. The final scene of the dockers resolving to shield the main protagonist is a case in point: the way the camera takes an eternity to tilt down the man’s arm to see (again with utmost slowness) his fist clench makes the moment so ludicrously portentous that it fails utterly to have any emotive impact. Soo too in the Christmas Day arrest, when the action is too slow, the cutting too imprecise, and the matching of action and image incredibly clumsy.

Hochbaum treads in Eisenstein’s path, both with the casting of non-professionals and in the use of symbolic details (Brüder’s red-tinted flag is surely taken from the red-coloured flag rising at the end of Battleship Potemkin). But whereas Eisenstein’s editing is incredibly dynamic, and his matching of action and image exhilarating and articulate, Hochbaum’s editing here is clumsy and heavy-handed. Indeed, the attempt to use editing and imagery to make his points goes against the realist atmosphere created by the locations and the casting of this self-identifying “German proletarian film”.

For the performers in this non-professional cast have wonderful faces, and (just as with the landscapes) I could spend a lot of time happily just studying them move and live on camera. The grandmother especially carries so much sense of a life and past in the way she holds herself and moves. But the main docker is not particularly arresting as a performer, and—even when he is just sitting, doing nothing—he feels less engaging than the woman playing his mother. When Hochbaum gives us dramatic close-ups of him speechifying, it’s a little underwhelming. I’d rather have spent my time with the women and child and seen how they went about their business. Surely it’s a failure of the film to adequately engage us with the people on screen: this is meant to be their story, as embodied by real dock workers. But I was never quite engaged by the human drama. The moments of human life were too dominated by clumsy message-making. I loved the scenes without any dialogue, more so because the dialogue itself was slogan-speak not real human speech. When nothing happens in this film, it’s beautiful. But as soon as the film attempts dramatic action, it becomes clumsy and heavy-handed.

Brüder was Werner Hochbaum’s first feature film, his only other silent productions being the short documentaries Vorwärts (1928), Wille und Werk (1929), and Zwei Welten (1929)—none of which I have seen. His cameraman was Gustav Berger, who appears to have worked on no other films other than those few silents by Hochbaum. All these silents were made under the aegis of “Werner Hochbaum Filmproduktion”, suggesting their independence from mainstream studios. The only information I can find on Hochbaum’s early career is in Klaus Kreimeier’s The Ufa Story (California UP, 1999, 287-88, 311; see also the German Wikipedia page on him). Hochbaum seems to have had an interesting life. Though homosexual, he was married to a dancer who died young in 1922. In 1923 he was tried for (and acquitted of) treason, suspected of being a spy in the pay of France. And despite being decidedly left-wing (working for Social Democrat papers in the 1920s, making “proletarian” films like Brüder), Hochbaum stayed in Germany after the Nazis came to power and continued to make films for UFA. But he was subversive enough as an artist to be expelled from the industry in 1939 by the Nazis. Conscripted into the army, he was ultimately excused duties on health grounds—and died in 1946 of a longstanding lung disease.

Given the rather obscure production, I suppose it’s a kind of miracle that Brüder survives, and in such good visual quality. The restoration notes for this version—broadcast on ARTE—state that the film was submitted twice to the censor, first in April 1929 (at 1722 meters) then in August 1929 (at 1989m). The original negative is lost and only copies of the first version of the film survive. The copy as restored by Filmarchiv Austria and the Deutschen Kinemathek in 2021 is 1732m. The copies used for the restoration must have been first-generation prints, for the film looks wonderfully sharp and textured. For me, the location photography is the film’s main appeal.

The score, from 2021-22, is by Alain Schmidinger and performed by members of the Berliner Philharmoniker. The ensemble (twelve players in total) produces something between a soundscape and a score. It blends real instruments with synthesized sound effects and, at two points near the end of the film, extracts from a recording of Telemann’s Oboe Concerto in C Minor (TWV 51:c1). Apart from the latter, the soundtrack is growling, bleak, restless, angry. The score certainly has an ebb and flow, but the tone scarcely changes: only the degree of aggressive angst varies. Walking down a street? Acoustic angst. Confronting your boss? Acoustic angst. Buttering bread? Acoustic angst. Punching a policeman? Acoustic angst. Settling down to sleep? Acoustic angst. The score has no tenderness. Not that the film has a lot of tenderness, but those moments which do—all involving the women—deserve some reaction, some softening, of the score. Quite why it includes the chunk of Telemann—surely extracted from another recording—is a mystery. For the contrast between Telemann’s concerto—all baroque elegance, restrained melancholy, emotive textures—and Schmidinger’s harsh, abrasive soundworld is so vast that it almost serves to make the citation seem ironic. Is it meant to enrich or undermine the emotive scenes around Christmas that it accompanies?

In summary, Brüder was a mixed experience for me. I certainly enjoyed aspects of it: the location shooting was fascinating to watch, as were some of the performers. But the film is very clumsy. It shows us a realistic world, but it cannot mobilize it into a convincing or emotionally complex drama. What moved me about the film were incidental details, its setting, not the narrative. But in one sense Brüder fulfilled its contact: I wanted to be gloomy, and it gave me my gloom.

Paul Cuff