In 1881, writer and activist Helen Hunt Jackson published A Century of Dishonor, an account of the racial and cultural persecution of Native Americans by the US government. She sent a copy to every member of Congress in the hope of influencing government policy. Her work received much attention in the public press, but Jackson wanted to do more. Moving to California, she embarked on a study of the way Native Americans were forced off lands that had formerly been guaranteed to them by the Mexican government prior to the US takeover of 1848. In 1883, she submitted a report recommending more land and support be given to the Native Americans of California. When a bill based on her recommendations was blocked by the House of Representatives, Jackson decided to make her case more public. Her novel Ramona (1884) is set in the aftermath of the Mexican-American War of 1846-48, and depicts the persecution of Native Americans by the US government. But its political message was less appealing to readers than its romantic treatment of love-against-the-odds and its depiction of Catholic missions in the former Spanish-speaking lands of California. Over 15,000 copies of the novel were sold by the time Jackson died in August 1885, ten months after the publication of Ramona.

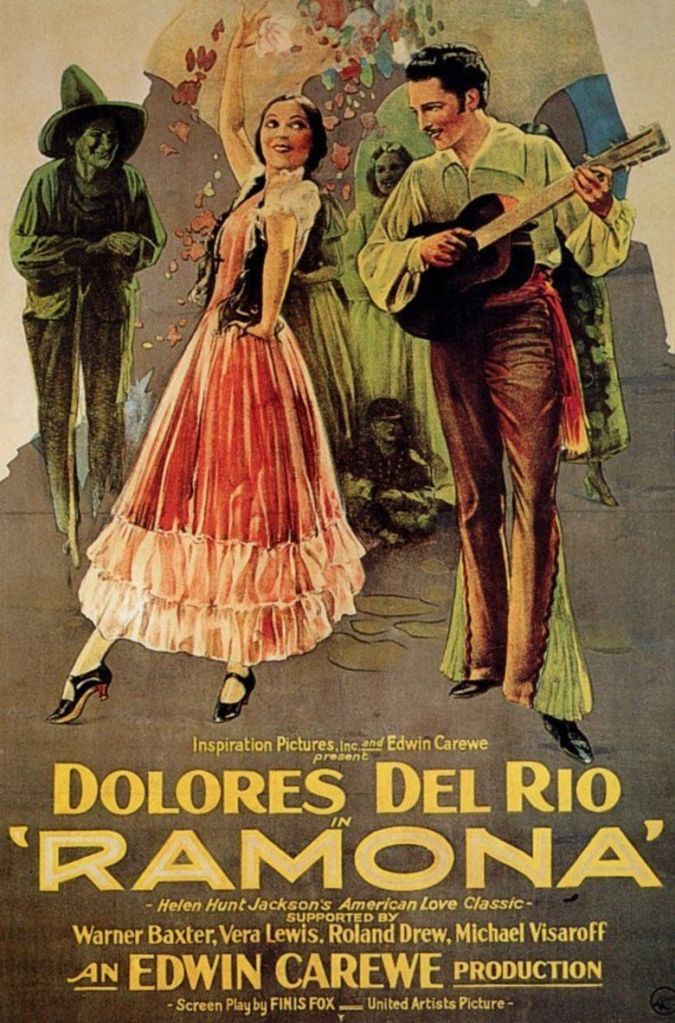

In subsequent years, Ramona was reprinted hundreds of times and helped kickstart the tourism industry in California. It was turned into a play shortly after Jackson’s death, and in the twentieth century the book attracted the interest of filmmakers. It was an obvious target for cinematic adaptation. The story already had a place in the public imagination, and the real landscapes of Ramona were on Hollywood’s doorstep in southern California. The book was adapted for the screen three times during the silent era. The first film was directed by D.W. Griffith for American Biograph and released in May 1910. At a single reel, it lasts barely seventeen minutes. The second was a feature film of substantial length (the AFI database lists it as “10 to 14 reels”), directed by Donald Crisp and released in April 1916; this version has been lost, save for a single reel. A second feature adaptation (of eight reels) was directed by Edwin Carewe and released through United Artists in April 1928. The films of Griffith and Carewe belong to very different industrial contexts, but their shared material makes for a fascinating comparison…

The story. Though each film emphasizes different aspects, they share the same basic narrative found in the novel. Ramona is the adopted daughter of the old Spanish household of Moreno. Señora Moreno is strict and forbidding, but her brother Felipe loves her dearly—and his love becomes romantic as they grow up. Alessandro is the leader of a team of Native Americans who are hired to do the sheep-shearing on the Moreno estate. He and Ramona fall for each other, but Señora Moreno forbids any involvement between them. She reveals that Ramona is herself the daughter of a Native American, a fact which makes her all the more determined to run away. Felipe is in love with Ramona but sacrifices his own happiness to help Ramona escape to be with Alessandro. The pair run away, marry, have a child, and settle—only for their settlement to be destroyed by whites. Their child dies after being refused treatment by a white doctor, and Alessandro starts to lose his reason in despair. Having moved to the remote mountains to escape persecution, Alessandro is killed after an argument with a white settler—and Ramona eventually returns to the Moreno estate, where Felipe lovingly awaits her.

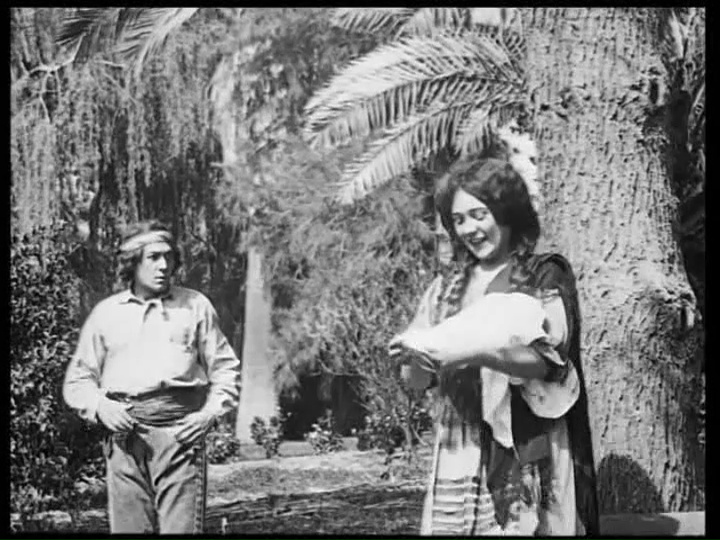

Ramona. In 1910, Ramona was played by Mary Pickford. Though a regular member of Griffith’s Biograph casts, Pickford had yet to develop her own reputation as an actress. Within a few years, she would become one of America’s most loved film stars, but here in 1910 she is an anonymous lead performer. (We don’t even get to see her famed blonde curls, for she wears a long black wig.) There are no close-ups, but Pickford communicates everything we need to know with her face and body. We recognize Ramona’s emotions through her hands clenching, her arms raising, her eyes widening, her energy or her stillness. If it’s a film of clear performative telegraphing, there are also moments of incredible delicacy. In the scene titled “Homeless”, after the couple have been evicted from their first home together, we see Alessandro and Ramona standing side by side. In Ramona’s arms is their tiny child. The two adults are hunched, the weight of unjust eviction on their shoulders. It’s an image of stillness, a tableau of defeat and resignation. But look at the tiny gesture Pickford makes with her fingers, stroking the underside of Alessandro’s arm. It’s a heartbreaking little gesture. It’s so gentle, so intimate. Ramona seems to know that there are no words they can meaningfully exchange, that saying or doing anything would only upset her husband further. So she just strokes his arm to let him know that she’s there.

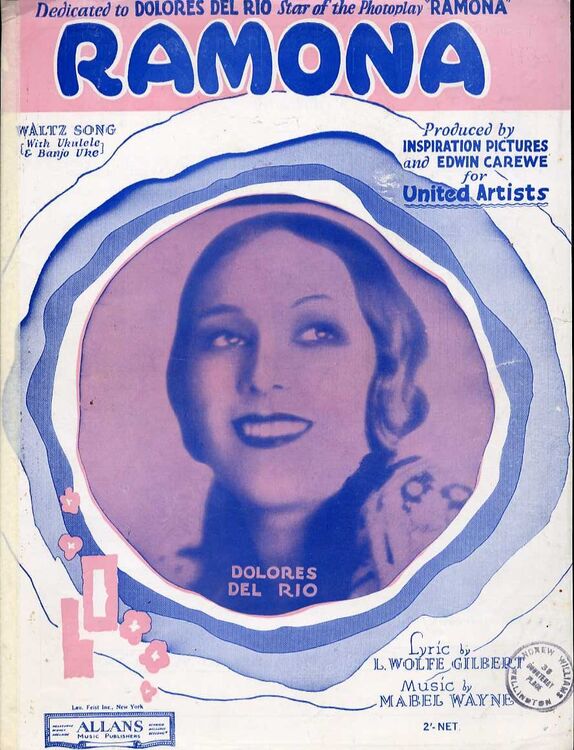

The Ramona of 1928 is the same character but a very different kind of screen presence. It’s not merely that Dolores Del Rio is Mexican and thus looks more “authentic” than Pickford and her dark wig. It’s that the 1928 film is built around its cast in an entirely different way. This later Ramona is a vehicle for the rising star of Del Rio. As the opening title states, this is “Dolores Del Rio in…”. After moving to America in 1925, Del Rio was contracted by Edwin Carewe—a man determined to make her a star, specifically a star of his films.

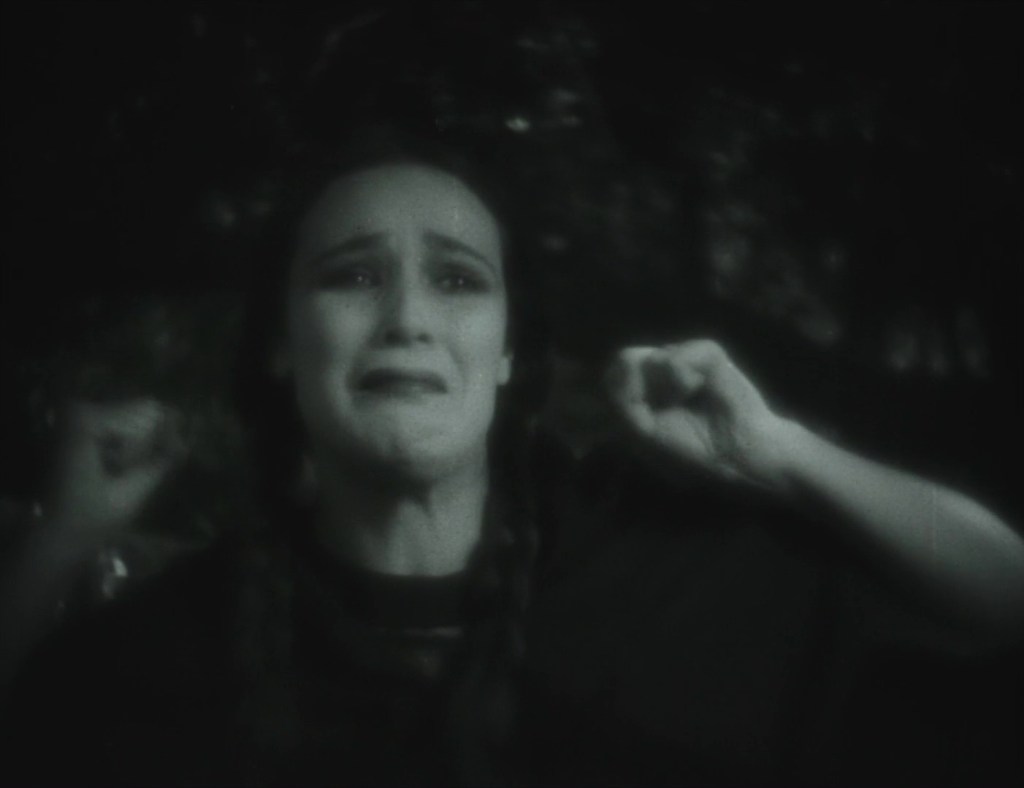

Del Rio totally dominates the Ramona of 1928. From the opening scenes, set a few years before the main story begins, we see her frolicking with Felipe around the landscapes of the estate. She runs, rides, jumps, falls, laughs, cries. Even in the later scenes, she is incredibly emotive. More attention is paid, of course, to her face by the editing, but it’s a bodily performance. This is most evident in emotional climaxes of the film. I’ve written elsewhere about Andrew Britton’s idea of female performers having the cinematic equivalent of operatic “mad scenes”: moments when the whole drama is focused on female performance and extreme emotions are expressed through her body. In the 1910 film, it’s Alessandro who gets a mad scene—per the novel, he loses his mind with grief after the death of their child. But in 1928, it’s Ramona who gets not just one but three “mad scenes”. In the equivalent narrative moment when their child has died, Ramona is praying inside the house while outside Alessandro builds a coffin for the child. The sound of his sawing timber is rendered visually: the saw is superimposition over Ramona kneeling in prayer. She covers her ears, weeps, breaks down. It’s all done in close-up, allowing Del Rio to embody the sense of grief and outrage the film has been fostering. A second scene occurs when Alessandro dies. After the sustained close-ups of Ramona grieving over the body, we see her race for help through the landscape (just as Alessandro does in 1910). Struggling through thick vegetation, her face and arms bloodied and glistening, Ramona ends up performing her mad grief in another sustained close-up. Carewe makes Del Rio go through every permutation of anger and fear and grief. But for me, the reality of the grief gets a little lost in the glamour of showing it off this way—certainly compared to the restraint of the 1910 film. Del Rio’s glistening body is as much the subject of our attention as the emotion she’s trying to convey. In Griffith’s film, the grief is purer, more raw. In 1928, Del Rio gets her last “mad scene” at the film’s finale of the film. Here, she is brought back to life by Felipe’s music. From a kind of stupor, she slowly rises, raises her hands, stands, then slowly breaks into a kind of confused dance—twirling her way back to full sanity and the recovery of her memory. It’s very stylized, slightly awkward, and not wholly convincing. Not that it’s Del Rio’s fault: Carewe has clearly arranged everything just as he wants, in this highly contrived fashion.

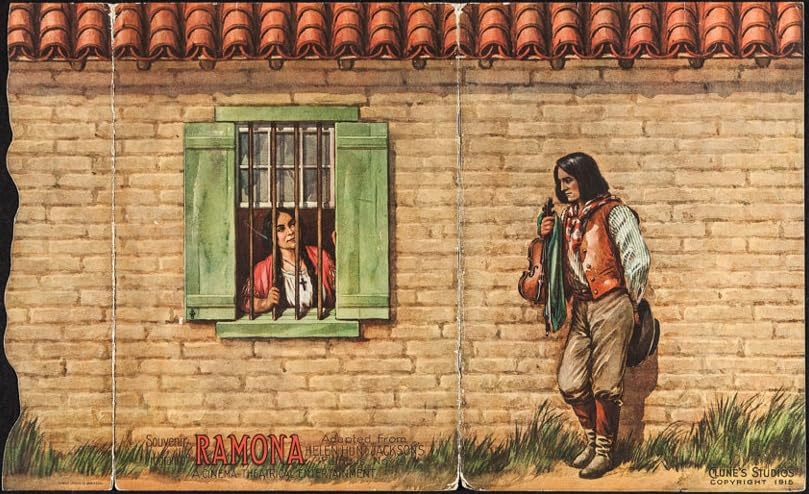

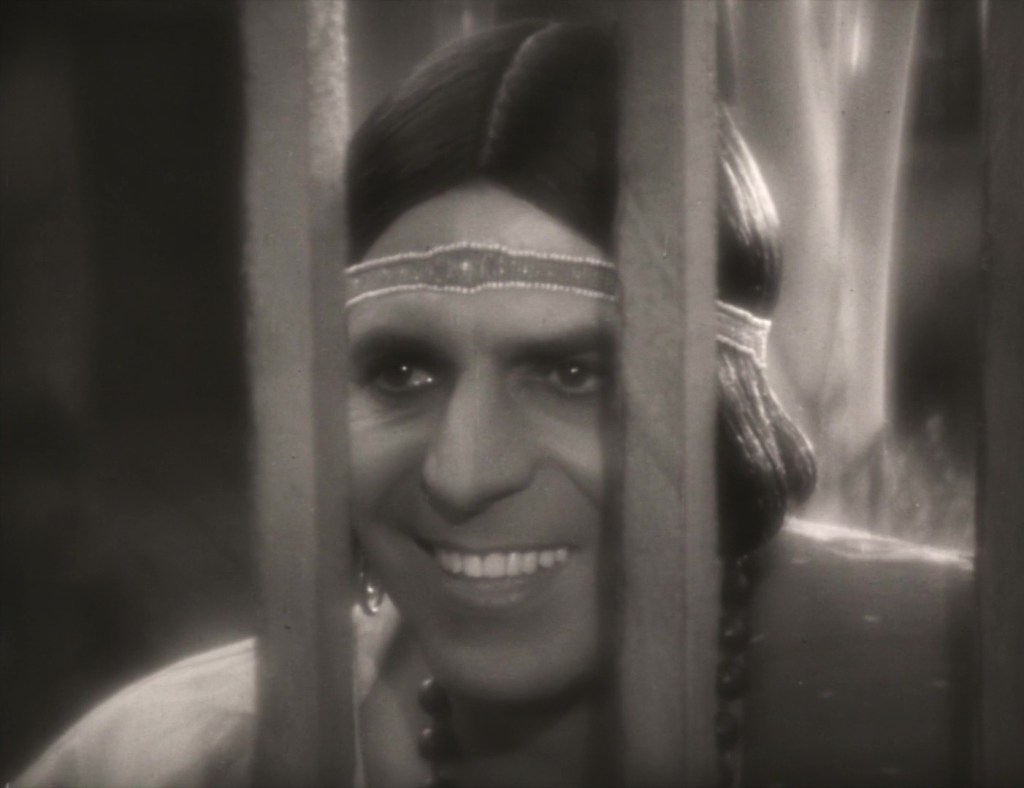

Both 1910 and 1928 films share one particularly evocative image of Ramona imprisoned at the Moreno estate. In the scene titled “the intuition”, we see Ramona behind the bars of her room—looking out, to try and see Alessandro. In the 1928 film, this same setting is developed into a site for the flirtation between the lovers, with Alessandro bringing Ramona flowers each day. I can’t find this image of Ramona behind the window bars in the novel, so Carewe may well have taken it from Griffith’s film—or from the 1916 film, the illustrated programme of which contains this same image.

Alessandro. The Alessandro of 1910 (Henry B. Walthall) offers fewer moments of subtle performance than that of Pickford’s Ramona. His emotions are clear to read, and (as noted above) he also gets a “mad scene” after the death of his child. Just as the Ramona of 1928, he runs with arms raised over his head across the landscape. The use of his cloak makes his gesture all the more grand, as though he were trying—quite literally—to fly from the scene of horror.

The Alessandro of 1928 (Warner Baxter) may be denied his “mad scene” but gets a lot more scenes of his own, apart from Ramona. We’re first introduced to him via the extraordinary image of him riding, half-naked into the Moreno estate. He dismounts and we see his whole upper body gleaming with sweat. It’s an amazing introduction, far more sexualized and showy than anything in Griffith’s film. Baxter’s Alessandro inevitably has more range than Walthall’s. Over the course of the film, we see him smiling, singing, laughing, making jokes—as well as crying, raging, despairing. There may not be quite as many lingering close-ups of Baxter as there are of Del Rio, but he is clearly a source of direct and sustained emotional engagement throughout the film.

Not that the 1910 film doesn’t offer us a sense of romantic feeling: it’s just that Griffith shows it differently. Alessandro first sees Ramona outside, on the edge of the forest. She walks off to the left of frame, without seeing him. But we see him alone, his gaze following her off screen. In the next scene, inside the chapel, Ramona is introduced to Alessandro, who then exits to the right of frame. Ramona is left alone, her gazing following him off screen. The mirrored framing of these two scenes, these two gestures, two looks, one after the other, is such a simple but such an effective way of rendering the impression of feeling. It’s economic filmmaking, and it makes us pay attention to every movement and every pause in the performances.

Of course, there is one obvious aspect of casting in these two films: both Walthall and Baxter are white actors playing Native Americans. (In passing, it’s worth noting that Griffith himself played Alessandro in a stage version of the novel, produced in 1905. Some details about his “authentic” costume are known, but not whether Griffith wore any kind of skin tone.) At least we are spared any effort to darken Walthall’s skin in 1910. Though the casting of white actors will understandably spoil the 1910 film for many modern viewers, it does have the consequence of eliminating any distinction between whites and “Indians” within the world of the film. The whites’ persecution of Native Americans is, in this sense, inexplicable: there is literally no difference in “race” between the people on screen. The idea of “race” and thus superiority/inferiority exists purely inside the heads of the characters.

In 1928, however, Baxter is given a subtle (but all too obvious, from our point of view) darkening of his skin tone. He also reveals his whole upper body, something Alessandro never does in 1910. Though Griffith doesn’t show us Alessandro’s bare-chested physicality, he does show the toil and sweat of his life. Alessandro is always burdened with heavy sacks when he passes Ramona outside her home. And when he pauses to try and steal a glance at her, we can see the dark sweat stain in his armpit as he struggles beneath the weight of his load. (I wonder also if his remaining fully clothed throughout is also a way of masking his all-too-obvious whiteness.)

Felipe. Ramona’s adoptive brother in 1910 is played by Francis J. Grandon, who has only a handful of moments in the film. The titles do not make it clear his relationship with Ramona or with his mother. But the simplicity of his gestures (the way he doffs his hat, gestures to others) and the modesty of his posture (the slowness of his movements, his bowed head in the final scene) makes it clear that he is a gentler character than some of the farmhands who obey his mother’s instructions. When Ramona rejects him, he simply bows and walks away—but the dignified sadness of his every gesture (first loving, then anxious, then accepting) make an impression. And after the lovers run away, Felipe sends back the riders sent by his mother to chase Alessandro and Ramona. The film offers no explanation as to why he does this, but (given the earlier scene of rejection) we sense a moral decision here: it’s one of the very few good deeds we see in the film. Felipe’s presence in the final scene, gently holding Ramona against his body, doesn’t have the emotional complexity the equivalent scenes have in 1928, but it’s moving nonetheless: it’s a man paying his respects, offering a gesture of sympathy that no-one else has.

The Felipe of 1928 (Roland Drew) is a much more significant character. Drew gives his character’s forlorn love for Ramona a lovely sense of pathos, without overplaying it. His acts of kindness are more evident in the film, and thus more emotionally ambiguous given his awkward status as sibling/potential lover. He has more of a role to play in 1928: it’s he who engineers Ramona’s escape by unlocking her room and distracting his mother. He also tracks down Ramona after Alessandro’s death and helps her recover her memory. But I do find the simplicity of Griffith’s ending more emotionally compelling. Because Felipe is only an occasional presence in 1910, it concentrates our sympathy more firmly on Ramona at the end. Nothing implies that Felipe will marry Ramona (per the novel and, by implication, in 1928), which makes the last scene of 1910 more tragic.

Señora Moreno. In 1910, this character—never named in the titles—is played by Kate Bruce. It’s a memorable performance. She visibly shakes with fury at being disobeyed, and her imperious gestures give you an immediate sense of character. In 1928, the character (this time properly credited as Señora Moreno) is played by Vera Lewis, who is a perfect match for Kate Bruce’s performance—just as threatening, just as imposing. But Lewis also gets to add a touch of humour to her performance. The slightly protruding teeth, the slightly bulging eyes when she sees Ramona disobeying her—they make the character more three-dimensional. The machinations of the plot, whereby Señora Moreno reveals Ramona’s Native American heritage, is accordingly more complex in the 1928 film.

Race. All of which brings us back to race. To state the obvious, these are both films that present a history of racial injustice while simultaneously perpetuating forms of racial injustice through their modes of representation. Of course, the 1928 film features a Mexican as Ramona and casts a number of Native American and Mexican extras—most evident in the staff of the Moreno household. But these non-white actors stand side-by-side with white actors in grease paint, most obviously the comic maid character played by Mathilde Comont. It’s great to see some genuine non-white performers on screen in 1928, but their presence also makes the wider casting of white actors seem even more glaring. (One also wonders how much these respective performers were paid.) The 1910 film scores less on this front, having an all-white cast—but (as I discussed above) this also raises an interesting question about how “race” functions within the world of the film.

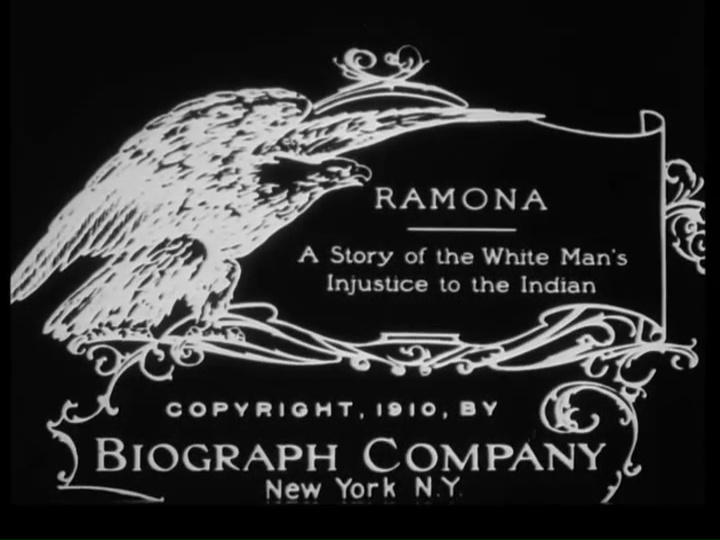

To return to the issue I raised at the start of this piece: to what extent are these films interested it the political message of Jackson’s novel? It seems to me that the 1910 film is more overt about its theme of racial persecution. In the opening title of the credits, Griffith spells out the theme in the film’s subtitle: “A Story of the White Man’s Injustice to the Indian”. After crediting the novel, the next title states: “This production was taken at Camulos, Ventura County, California, the actual scenes where Mrs Jackson placed her characters in the story.” This not only ties the film to the book, but to a sense of verisimilitude: here is history being recreated in the very site it happened.

The equivalent subtitle in the opening credit of the 1928 film presents Ramona as “Helen Hunt Jackson’s Love Classic”. This is much more in line with how the novel was popularly received, and not how the author herself would have seen the story. Also worth noting is that the 1928 film was not shot in Southern California, but in Zion National Park, Springdale, and Cedar Breaks National Monument—both in Utah. The photography (by Robert Kurrle) is very nice to look at, but the landscapes are never used in the same dominating, powerful way as Griffith uses them in 1910.

To illustrate their respective interest in ideas of race and land, just look at how these films deal with the raid on Alessandro’s village. In 1910, the scene immediately prior to the raid is the scene where Señora Moreno furiously expels Alessandro from her estate. The image of her outstretched arm and angry face is the last we see prior to the raid. Is there an implication here that Señora Moreno is responsible for the raid? Griffith leaves it unclear, and in doing so makes the sense of injustice feel more pervasive. The fury of one white settler is immediately followed by the devastation wrought by others. Whether the latter are motivated by Señora Moreno, the two acts of expulsion are linked by the film’s editing. Griffith also places the raid after Señora Moreno finds out about Ramona’s romance but before she runs away. In 1928, the raid comes only after they have run away and settled down to married life. Griffith thus makes Alessandro homeless twice in the film: once before Alessandro has settled with Ramona, then again after they have their child together. In this, it is closer to the novel: in Jackson’s original narrative, the couple are forced to move several times before they settle in the mountains.

The two depictions of the raid itself are very different. In 1910, we see the raid in an extraordinary composition in depth. In the background, at the bottom of the valley, is the smoking village and tiny specks of raiders flitting from the buildings. In the foreground, looking down into the valley from the mountainside, is Alessandro—gesturing in fury at the horror he witnesses. The photographic quality of the scene, encompassing both extreme depth and proximity, is a miracle for 1910 and a credit to the talents of Griffith and his cameraman Billy Bitzer. Framed with the events visible behind him, Alessandro’s raised arms and visible despair attain a tremendous sense of tragedy and impotence. It also marks the first visual connection between the Native American character and the land around him: these giant landscapes will come to define the film’s final scenes.

In the 1928 film, the raid is played out at much greater length and in grisly detail. With the camera cutting and tracking through multiple locations around the settlements, we see dozens of men, women, and children (many of them non-white performers) gunned down. We see plenty of blood and plenty of deaths in close-up. But the film also fudges the who and why of what’s being done. The massacre is perpetrated (we are told in a title) by “marauders, motived by hatred and greed”. Griffith’s title is more blunt: “The whites devastate Alessandro’s village”. We’re in no doubt who does the massacring. What’s more, by specifying the broadest category of perpetrator (simply “whites”), Griffith directly links this event with a broad cultural effort of persecution, dislocation, and genocide.

When it comes to the death of Alessandro, the novel and the 1928 film both give the white shooter a clear motive for the killing: Alessandro has stolen (and admits stealing) the white man’s horse. But in 1910, Griffith eliminates this motive entirely. The scene’s preceding title is simply: “This land belongs to us”. In a film of so few titles, using one of these to repeat a phrase already given in an earlier title is significant: it draws the death of Alessandro back to the same theme of persecution that has dogged him throughout the film. As with the raid scene, Griffith frames this second act of violence against the background of the mountains. From the right of frame, a white settler steps forward. His arm describes a wide arc before pointing to himself. This gesture is as crude as what it signifies: all this is mine. Alessandro calls out and is shot down. There is no backstory to the shooter, no possible motive given or implied other than greed and contempt. This is the only on-screen death in Griffith’s film, which makes it all the more brutal. Unlike the massacre of the 1928 film, Griffith doesn’t sensationalize what we see. The shooting is almost casual, certainly callous—done without thought, or need to rationalize. The white simply shoots down Alessandro, then shoots him again once he falls. (This detail is in the novel: “standing over Alessandro’s body”, the white farmer “fired his pistol again, once, twice, into the forehead, cheek” (427).) In 1928, there is shot-reverse-shot cutting between Alessandro and the shooter, and we see Alessandro clutching his chest before falling. There is a second shot fired, but the way the camera has shown us the details of the shooting makes it (to my eyes, anyway) less brutal than in the 1910 scene.

Culture. These different strategies of representation are also evident in the way the films deal with the wider culture of 1840s California. The novel was inspired by, and makes a great deal of, the Christian missions and their relationship with the Native American population. The 1928 film makes much more of this religious aspect, packing very many scenes with crucifixes, statues, icons etc. While Señora Mareno is first seen clutching her rosaries and crossing herself, the idea of religion is not part of the systems of cultural oppression evident in the film. In fact, the Christianity of both Ramona and Alessandro are foregrounded in a way that the 1910 film only hints at or implies. Thus, in 1928 Alessandro is blessed by Father Salvierderra as soon as he arrives at the hacienda and then joins in the hymn of praise before working (it is his voice that first catches Ramona’s interest). Though the marriage scene is brief (scarcely longer than in 1910), it has a more elaborate altar and places the priest more prominently in the centre of the image than in 1910—where the scene is defined by its sheer sparseness. But it’s Ramona who gets to interact most with statues of the Virgin Mary and the infant Christ, both at the Moreno ranch and in her home with Alessandro. There is even a kind of pieta when her child dies: we see the infant laid over her lap per the classic Christian imagery.

In Griffith, everything is much more low key—less glamorous and less glamourized. Like the sparse church where the couple are married (which lacks even a cross or altar), the symbols of Christianity are minimal and humble. The only cross we see outside the confines of the Moreno home is the meagre cross, formed from two tied sticks, above the unseen grave of the infant. The sight of this cross is moving because it speaks of their poverty: it’s a mark on the landscape that carries great weight of feeling and meaning for the parents, but which looks utterly vulnerable. That thin, imperfect cross looks as though it will blow over or fall down as soon as the parents have left the scene. As the framing implies—with the grave and body itself buried, visually speaking, below the bottom of the screen—these human lives are part of the landscape, inevitably to return to the land. The cross is fragile, ephemeral—and so too are the lives of those who raised it.

Time. The synopsis I offered at the start of this piece was a simplified version of the story as given in both films. But the novel offers a much untidier story than in either film. Firstly, the lovers’ life together is interrupted several times by the actions of white settlers, not simply once (in the 1928 film) or twice (in 1910), before Alessandro is killed. Another important difference in the novel is that the couple have a second child after the first one dies. This second child survives and accompanies Ramona back to the Moreno estate. Felipe marries Ramona and thus adopts her daughter. The novel also reveals that Ramona and Felipe have more children of their own, but that her daughter from Alessandro (also called Ramona) is their favourite.

The length and complexity of events in the novel makes the 1910 film all the more astonishing for its simultaneous scope and brevity. There are just seventeen intertitles and thirty-six shots in the entire film. The titles are mostly straightforward descriptions (“The meeting in the chapel”), but others are more evocative (“The intuition”). Condensing a 300-page novel into seventeen sentences (one of which is a phrase repeated from an earlier title) is quite a feat. It also propels the story forward with a momentum that I find incredibly moving. Every scene, every shot, plays out slowly, yet whole years pass between scenes. It’s as if an entire life, lived out in real time, has survived only in these brief fragments. The film’s rhythm makes the narrative feel more inevitable, more tragic. We process remorselessly towards the end, the narrative compelling the action forward in leaps and bounds. The film—for me—has a kind of magical mode of storytelling that moves me every time I see it.

The 1928 film has a very different rhythm. There are temporal ellipses, but they produce nothing like the same effect. The first scenes of the film are a kind of prologue, for there is a (rather surprising) title announcing: “After three years at the Los Angeles Convent, Ramona came back to the old hacienda…” It’s worth remembering that the lost film of Ramona from 1916 was significantly longer than the 1928 version, and its cast features three different actresses as the child, young adult, and older Ramonas. The progress through time is sudden in Griffith’s film, but the brevity of the film produces its own logic. Carewe’s film awkwardly tries to cover a lot of ground but without exceeding the bounds of a standard feature length film (80ish minutes). Thus, although the film elaborates each episode at great length, we still end up skipping chunks of time: three years at the beginning, then—after the lovers elope and marry—we read that “Several years have passed”. The passage of time doesn’t move me as it does in Griffith’s film. (I still haven’t quite worked through this impression, and I will doubtless have to return to it in another piece.)

Endings. Time also functions differently in the way these films end: each has its own way of imagining what happens after the last scene. Indeed, Griffith ends his film with no sense of an “afterwards”. There is no suggestion of a life with Felipe, no time on screen for Ramona to grieve and mend. Alessandro’s body is on screen, Ramona’s grief is all too apparent. The film sends us away with an extraordinary final image of defeat and desolation.

In 1928, we have a very different ending. As described above, Ramona dances her way to sanity and is cheered by the whole household of the Moreno estate. “Why, it’s just as though I’d never been away” she says, coming to at the end. Troublingly, this leaves the idea that one can erase the memory of her marriage and her alignment with the Native Americans of the settlement. She has now rejoined the white family, with no baggage from her former life. In the novel, of course, she has a daughter from Alessandro—a permanent reminder of her first marriage. In 1928, nothing remains—but Ramona happily resumes her former life.

Restoration. On the topic of ellipses, I must add that there is also a strange ellipsis later in the 1928 film, when the child falls ill and dies while Alessandro is out trying to find a doctor. The film offers no sense of continuity here: how much time has passed? How long has Alessandro been gone? We aren’t told (in titles) and don’t see (in images) quite what’s happened to properly set up this scene. Are these odd continuities the result of missing footage? As so often, the restoration credits at the end of this version of Ramona do not state the length of the film, either in 1928 or in 2018. According to the AFI, the original length was 7650 feet (2330m), which at 24fps would be approximately 84 minutes of screen time. But the AFI catalogue gives the length as 78 minutes, and the 2018 restoration (excluding modern credits) runs to 82 minutes. The 2018 restoration is based on a German print held by Gosfilmofond in Moscow, but it’s unclear what—if any—textual differences there might be between this and the version shown in the US in 1928. What is clear is that the intertitles are digital replacements to the lost English originals. They stand out as very obviously digital and don’t have anything like the same texture as the film images around them. I also have a very particular bugbear with many digitized North American intertitles, which is that they often don’t change neutral inverted commas into typographic ones (i.e. they have “text” rather than “text”, “text’s” rather than “text’s”). Some of the old David Shepard restorations released on Image DVDs (and, latterly, on Flicker Alley) often had the most appallingly formatted replacement titles: they were aesthetically alien to the work around them and frankly ugly. No variety in fonts, no effort to match the original designs. They all looked like they’d been copied and pasted from a notepad.txt document without any formatting (or, sometimes, spellchecking). The formatting of this restoration of Ramona has a strange mix: the double inverted commas are typographic, the single inverted commas neutral. Why? Do these match anything in the original titles, or any titles in other films produced by this studio?

The 1928 film also originally had a synchronized music soundtrack, complete with the original song “Ramona”. Though the melody is used in the new score accompanying the 2018 restoration, the original recorded music track is not used. (I, for one, am grateful that the soundtrack is not extant: I do hate the grotty acoustic quality of soundtracks affixed to silent films at the end of the 1920s—especially when they have a tie-in song to sell, which are inevitably ghastly.) Instead, we have a score performed by the Mont Alto Motion Picture Orchestra (i.e. a small ensemble). The music is well-chosen and provides a solid, melodies accompaniment to the film. The score respects both the mood of the film and the on-screen references to music etc.

The 1910 film (per its release on Blu-ray as part of a now OOP Mary Pickford set) has a mildly irritating score—something of a specialty with Mary Pickford Foundation restorations. It’s fine, but I could do without the intermittent drums. The restoration offers good quality video but lacks any tinted elements, which you suspect would have been present on prints circulating in 1910. The lovers’ escape seems to occur in the evening or night and should have some colour change to make this clearer. Many of the recent (and ongoing) of restorations of these Biograph films have been tinted and I’d love to see a new restoration of Ramona this way.

Summary. As is probably clear by now, for all its faults, I prefer the 1910 version of Ramona to the version of 1928. Del Rio and Baxter give their best, but the film never moved me. What’s more, I’m sure I will remember the images of Griffith’s film for far longer than those of Carewe. The 1928 film is pretty but the 1910 film is beautiful. I’m also drawn to the latter for the fascinating way it upends our expectations of Griffith. Here is the maker of The Birth of a Nation (1915), standing up for indigenous peoples and showing the violence of white settlers. His adaptation of Ramona is a little gem among his vast output for Biograph, and we can surely admire it without forgetting what came afterwards. The film’s brevity, restraint, subtlety, and sense of political outrage still make an impact, whatever issues we may (and should) have with its casting or its maker.

Paul Cuff

3 thoughts on “Two adaptations of Ramona: 1910 (US; D.W. Griffith) and 1928 (US; Edwin Carewe)”