Day 3 takes us to Italy in 1917, from whence come two fragments and a feature film—all preserved in unique prints from the Eye Filmmuseum, Amsterdam…

La Vita e la Morte (1917; It.; Mario Caserini). It is life and death, or the first act of it. We begin with the drama underway. Choices have already been made, fates motivated. An untrustworthy figure bends beside an inert woman. There are references to Gautier’s letters, which Leda carried with her. Here are a mourning husband and child, mourning prematurely. The screen’s bluish wash is a kind of mourning, so too the faded richness of the blacks. The screen has been washed with passing time. Paul lifts Leda’s inert body. Fragments of Leda’s boat, washed ashore. A gleaming coastline, dipped in pale blue. “Poor Leda.” But at the house in Lausanne, Leda pants in bed. (Her eyes roll towards the camera. We see you, Leda.) Paul stands sinisterly over her, warning a servant not to let Leda escape. (The framerate is palpably slower-than-life, as though the fragment were dragging its feet, anxious to extend what remains of its runtime.) Paul is pleased to overhear sailors saying that Leda is dead. The gates are toned green, washed ochre. A glimpse of park or gardens behind bars. Paul’s servant is drunk, sitting guard over a disconsolate Leda. The husband reads a letter fragment from Gautier to Leda. Perhaps her death was best for them all? The child delivers flowers to mama’s grave: the water’s edge. Child and nurse turn to walk away. The film ends. An intriguing, evocative fragment—preserved in this Dutch print and nowhere else. You can find the whole plot on Pordenone’s online catalogue, but the magic is here: the fragment invites us to imagine the lost parts of the film, or simply to contemplate its loss, and ours.

[Italia Vitaliani visita il regista Giuseppe Sterni per discutere del suo ruolo in “la Madre”] (1917; It.; Giuseppe Sterni?). A studio. The director, lost in concentration. Curtains are opened. Nitrate decomposition enters, followed by Italia Vitaliani. She takes off her coat. The director brings her over towards the camera, shows her the screenplay. (A close-up of the title page.) He opens the script, begins to read. Vitaliani settles to listen. The film ends. It’s a truncated trailer for the feature we are about to watch, a glimpse behind the scenes. Yet it is also a staged performance, an invitation to see the relationship between author and actor—and the chance for the author to be an actor.

La Madre (1917; It.; Giuseppe Sterni). The two lead characters, in their own tableau: a young painter, Emanuel, and his mother. (And we recognize them both from the previous film: Emanuel is played by the director himself, while the mother is Italia Vitaliani—made to look older with her greyed hair.)

Part One. The dark interior of the Roan’s village bakery. But Mrs Roan’s son prefers painting to baking. Outside, glimpses of a sun-filled street. The dark shadows of an awning. The texture of an old wall, fragments of ancient posters. The sunlight is harsh, the shade thick: it is all palpably real, palpably parched.

A visit from an artist and connoisseur, to appraise a painting found behind the wall of the local church. The group are invited to Emanuel’s studio. The men’s faces are ambivalent. They say Emanuel lacks the resources to be a painter. But there is an offer to share the artist’s studio. Emanuel’s mother says he should go, that she will stay and earn money. Two days later, he leaves.

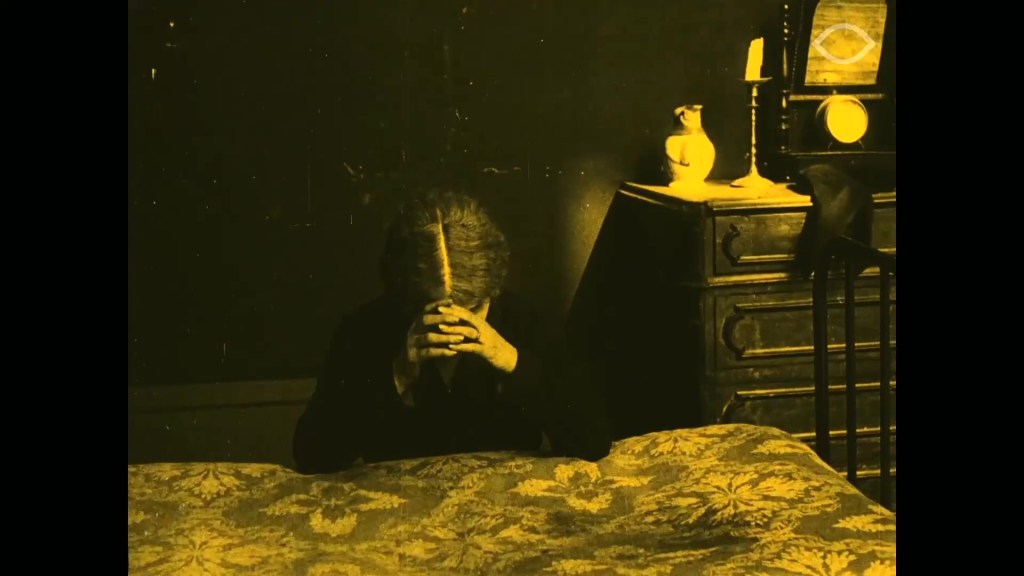

The mother, alone. Her room. Dark walls, small patches of light. She kneels to pray at her bedside. A quiet tableau of devotion, of moderate means, of private emotion. (Shared, of course, with us.)

A few weeks later, she makes the journey to town to see him. The world of rural transport, c.1917: a donkey and cart, a wait at a train station.

Emanuel’s work has been rejected for not sticking to known rules. He cannot pay his model.

Mother arrives. On the steps, a small black dog drowsily raises its head. Mother shuffles upstairs. She enters the studio, presents the two artists with some carefully wrapped bread—and some coins for Emanuel. (Now a letter from Isabella, his model, who returns a ring and says she cannot visit him again on instruction of her mother.) The artist explains that Emanuel is ruining himself over Isabella. Emanuel goes to see Isabella, but his conscience gets the better of him and he cannot offer the money given him by his mother to keep in Isabella’s good books (or the good books of Isabella’s mother). Mother stays with Emanuel, to “protect him” amid the temptations of the town. (Unspoken thoughts, unvoiced rivalries, unmentionable acts.)

Part Two. Emanuel is a success, but Isabella has “stolen” his heart from his mother. She arrives, the mother shuffles away to wipe away a tear in private. It’s another little tableau, this image of the heartbroken mother. But Vitaliani doesn’t overmilk our sympathies: hers is not an outlandish performance, but a disarmingly simple one. And her moments of solitude are just that: moments only.

Emanuel returns after a night out. He is well dressed these days, but he can hardly walk this night. His mother appears. He laughs off her concern. She warns him off Isabella, saying that she will ruin him. Emanuel grows cross. His face looks down in a scowl. Hers—in a patch of light, made gold via the tinting—looks up, and the camera sees her grief, invites us to empathize. Later, Emanuel is asleep in bed. His mother tiptoes in to tuck him in and kiss his brow.

“Make him listen to the advice of his sad and grey little mother!” she begs of Isabella and her mother the next day. Isabella laughs her off, says she’ll go but that Emanuel will beg her to return.

The son, before a mirror. He barely looks at himself: it is for us to see the two of him, his two roles, his two choices. His mother awaits, expecting him to reject her in favour of Isabella. “Do you really love her?” she asks. “Do you love her more than your unhappy mother?” She is his inspiration, he replies, the only one capable of sustaining his success.

That afternoon, as Emanuel contemplates his latest portrait, news comes from Isabella that she and her mother will never see him again until his mother apologizes. Mother tells him Isabella will ruin him. She struggles with her son, even grapples with him physically. The elder artist enters. “You need inspiration? She’s right in front of you!” Yes! He will paint his mother! He blacks out the painting of Isabella and begins feverish work on capturing his mother’s praying form.

Six months later. Back in the village, Mother Roan is beneath a large portrait of her son. She goes through his childhood clothing, an old photo, a shoe… A pain in her belly. She stumbles against the dresser.

Meanwhile, Emanuel’s portrait of her is nearly complete. He sends her a letter: the painting will be his greatest success. She is overjoyed but clutches her chest.

The exhibition: Emanuel’s maternal portrait wins the prize. The camera pans from the portrait through the empty gallery, pans right to left until it meets the incoming crowd; then pans left to right back toward the painting. The film cuts from a close-up of the image to the real sight of the mother prostrate in bed.

That night, he sends her word that he will be with her the next day. But no sooner does she read his words than she collapses. The next day, she is helped up and into a chair to receive first a doctor then her son. She wants everyone to hide her “grave news” from Emanuel. Emmanuel walks through crowds of locals who greet him like a returning hero. He is feted all the way home, where his mother is helped to her feet to see the crowds outside rejoicing for her son. No sooner than they embrace does she sink into a chair. “Now I can die happy.” The crowds cheer for Emanuel outside. He goes to the window to greet them. While he is at the balcony, his mother stands—then falls slowly back into her chair. From the green tinting of the outside view, the son returns to the burnished gold of the interior light and falls weeping at his mother’s side. (Her features are almost lost in the patch of light that illuminates her head: it’s as if she were already somewhere else, already effaced.) Two girls enter with a crown of laurels for the artist. He takes it and lays it at his mother’s feet. “Rest in peace”, he says—and we cut to an image of him before her angelic tomb. The End.

Day 3: Summary

A curious trio of films. The fragment of La Vita e la Morte certainly intrigued me and made me want to see more. Leda is played by Leda Gys (clearly, she stuck close to her on-screen persona, or at least her screen name). We saw Gys at last year’s Pordenone in Profanazione (1924). I thought the later was perhaps the weakest film of the 2022 streamed films. I was more intrigued by La Vita e la Morte, though I recognized Gys’s big, rolling eyes at once—her performance style didn’t seem to change much in the seven years between these films. It’s always fascinating and moving to watch a film in a state of ruin. And with such lucid filmmaking—each shot a tableau with its significance carefully laid out in deep composition—it is easy to be drawn into the glimpse into this lost on-screen world. But I wonder if the whole would live up to the promise of the fragment?

The staged prelude to La Madre was a lovely way to segue to the main feature. Even the existence of the former is historically interesting. I have a fondness for these promotional scenes of filmmakers that presage their own work. Someday I will write a piece on such appearances in the silent era—it’s a curious little theme in the 1910s, when directors became more prominent in the marketing of their productions.

As for La Madre itself, it’s a well-made film. And it’s a well-performed film. But I can’t say I wholly enjoyed it. The sympathetic piano accompaniment by Stephen Horne was a strong compliment, but I was never quite moved. Vitaliani’s performance is subtle, realist even, but the plot is so obvious that it’s difficult to be drawn entirely to her. It reminded me of Henri Pouctal’s Alsace (1916), in that another major theatre actress (in the French film, Gabrielle Réjane; here, Italia Vitaliani—a relative of Eleonora Duse) plays a dominating mother who forces her son to break off a romantic relationship with the “wrong” woman. But whereas Pouctal’s film pushes that plotline to the extreme of the mother essentially getting her son killed, in La Madre it is the mother who dies to prove her point.

Besides, La Madre takes too long to give any firm indication that the mother is right about Isabella. The first scenes with Isabella suggest noting more than young love being thwarted by interfering parents. Only when she laughs at the mother’s pleas does Isabella reveal herself to be less than a victim. But even then, Emanuel’s partygoing is never clearly linked with Isabella: only Mother insinuates that the one is the cause of the other. Unlike Alsace, where the mother’s rivalry with the daughter-in-law is pushed to insane, murderous extremes, in La Madre the rivalry is all rather tame. The mother is too self-pitying for us to feel so much pity for her.

So, in viewing La Madre, I fell back on the other pleasures of the film: the realistic settings and real streets, the rich textures of costumes and environments, the warm tinting and toning. It’s a simple, effective rendering of the story it wishes to tell. Is La Madre a great film? No. But the point of festivals like Pordenone is to show us things we would never otherwise see, and to enrich our understanding of the silent era as a whole. I have seen, I have learned; I am content.

Paul Cuff