Day 7 begins in 9.5mm and ends in 35mm. First a curated look at silent footage shot by members of the public up to the 1960s. Then to a truncated Czech print of a Mae Murray feature from the heart of the jazz age…

9½: Film in 9.5mm, 1923-1960s (Curated by Anna Briggs, Michele Manzolini, Mirco Santi)

The first film: an invitation to buy and use Pathé-Baby, to “immortalize our memories.” So here are other people’s memories. In living rooms. Smiling families film their own filmgoing experience at home. (Cigarettes are offered, films gathered. One wonders at the fire hazards of private use. The family munches chocolates. The light goes off.

The flicker of sprocket holes in the centre of the frame. A child hands from a beam. A balloon ascends from an amphitheatre, dropping pamphlets to the mostly empty stadium. Italian flags borne aloft. Red and yellow and blue and green balloons in colour. A man, in red, shoots a gun. He is suspended in the air, seen against a rocky cliff. A crowd watches. He crawls across the image. The camera ascends via a lift, through metal supports, into the sky above a city. We are on an aeroplane. We come to land (the image goes blank). Two children play with a model aeroplane. They climb a slope, send the plane soaring away—into a treetop. At home, a man plays with filmstock. A woman in a hat poses outside, looking steadfastly away from the camera. We have jumped continents. East Asia. Where next? A door is locked. A car drives away. We drive. Into the mountains. Dirt roads. A tractor. A hiker. Signposts flash past. We aboard a train, climbing. Heads poke out of the window. The view. a bridge. Below, huts. Where are we? In a cat again. Along treelined roads. We spy other cars. People. A fire. Cooking. A picnic in the hills. A repair on the road. Women stare at us. (Why aren’t we helping.) Winter is upon us. children. An ice palace. Icy skating, in weak colours, on slate-blue ice. Gently tinted images from home. Close-ups of long-lost relatives. Margaret and Vera, signposted. Mother and father, grandparents, aunts. A meal together, in—where? France? Close0ups inside. Close-ups outside. Skipping from country to country. Where are we? Other languages come and go. Children embrace. Parents show their children off to the camera. A woman paints a child. Another child, performing for the camera—an elaborate mime, gestures. Are we in Japan? The sea. A horizon. Waves. Cars aboard a ferry. Canoes. Rivers, boats, rivers along different continents, in different tints—rose, amber, turquoise. The seafront. Light. Days out. Beaches. A huge crowd beside the pool. A brass band. A jazz band. Couples in swimwear dance. A man films (he too is filmed). A woman dances on a doorstep. A street party. People in costume. Communities in the street. V.E. Day? A wedding in the 1920s. men swimming and rolling down a sandy bank. Glasses. Pathé’s logo silhouetted through the glass. Abstract visions. Cooking, heating, washing. Dumpling fry. Food is served. A clock. Time is passing. Tinned cherries. Stop-motion tins, toys. A gramophone turns. A fire is lit. fireworks. Faces at night. Blu yellow red green, the colours morph one into the next. The fire burns pink. The film ends. (Or does not end: we get a montage of all the films with full credits, dates, locations.)

Circe the Enchantress (1924; US; Robert Z. Leonard)

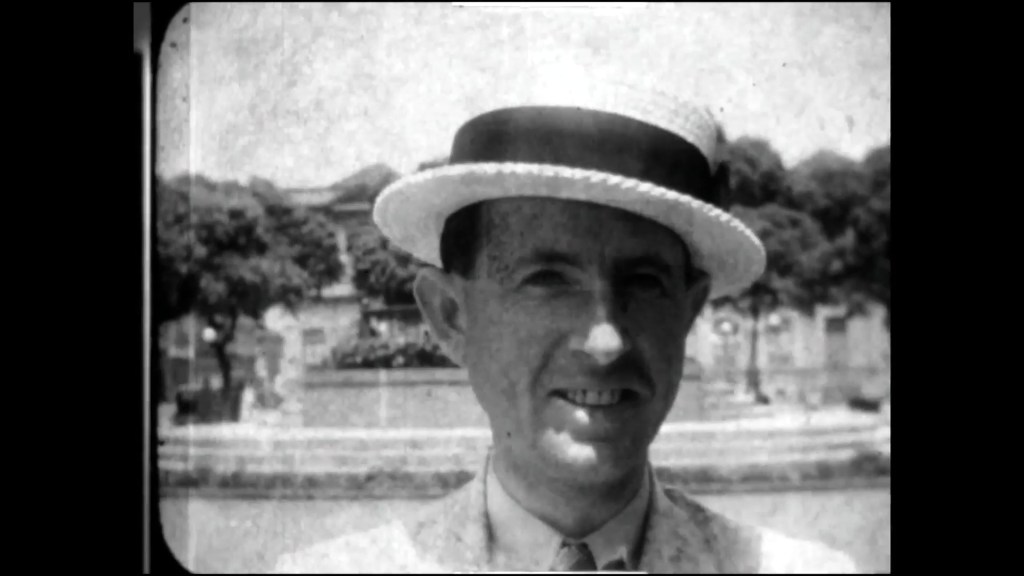

A vision of the ancient past (with Czech titles, to further mystify and enchant): here is Circe “the siren daughter of the sun”, the seducer and destroyer of men, who transformed them into pigs. Mae Murray, vamping delightfully amid a crowd of ancient men, then a crowd of jostling pigs.

Here she is in the modern world, Cecilie Brunner, who “takes as much as possible and gives as little as possible”. Around her, scoundrels, frauds, poseurs. Close-ups of the guests. Her two suitors: Bal Ballard, a stockbroker by day and lothario by night. Jeff Craig, a younger man who is madly in love with Cecilie. (Cecilie blows smoke into his face.) Madame du Selle quizzically looks at an empty space: Dr Van Martyn, a renowned surgeon and neighbour. Who is he? Cecilie laughs, dips a cherry in some champagne, and bites. Someone bets he won’t even show (Cecilie stops chewing on the cherry).

Dr Van Martyn (James Kirkwood) turns up. An older, vaguely fatherly type. Very different from the crowd within. One of Cecilie’s camp male friends stands gives the doctor a provocative wave. (The doctor gives him a stern, suspicious eye.) Indeed, he gives all the guests a faintly disgusted eye. Cecile breaks bread with the doctor. When she says that his ending up with the bigger half means she will bring bad luck into his life, he merely says that he isn’t superstitious.

“St Nicholas” arrives: a man laden with jewels, one of which he helps put on Cecilie’s ankle. Jealous rivals start a fight, so Cecilie leads them into the fountain to cool off. Cecilie wiggles her way provocative from the pool towards the disgusted doctor. Is there game too rough for him? “I know better than playing with Circe”, he says. But the one man she couldn’t seduce was Odysseus—isn’t that right? “A wise man”, the doctor replies.

Cecilie in her room, preparing to make men “dance to her music”. She prepares to dress up in her most provocative clothes, but the doctor has gone home (to pet his dog sadly before a photo of an unknown woman). She phones him anyway, to gently reprimand him for not saying goodnight. Is he afraid? “I don’t know about women like you”, he says. She is upset. She sits for a moment, looking vulnerable. She draws her legs up to her chest. She looks for a moment like a girl, afraid and alone. She goes to a draw. “Memories surface”. There is a hidden story here, a reason why she became the woman she was. We see into her diary. She once wanted to be a nun.

A flashback to the nunnery. Mae Murray with a pigtail, looking remarkably convincing as her younger self. But she is on the outside of the gates. A baker passes, sees her legs, pulses visibly with desire. He grabs her, she runs, he chases, forces her to kiss him. It’s a scene of primal assault. (One imagines that in the original, US, version of the film, this flashback led to more scenes of this nature: Cecilie’s history of exploitation and abuse at the hands of men.)

But “Circe drinks from the cup of oblivion”. Dissolve to the present: Cecilie dancing, drinking, smoking, as a black jazz band play madly rhythmic music. (“But Cecilie cannot forget.”) The camp friend—now half in drag, calling himself “the queen of the fairies”—starts the party dancing. They enact a parody of the film’s opening scene of ancient sailors and pigs. Cecilie dances, shimmies, struts, poses. (Cut to the doctor, reading a book before the fireside.) It’s an absurdly delightful sequence. (And Donald Sosin’s music is a scream.) But the memory of that last scene—the memory of a kind of violation of innocence—hands over it, over her, over us. The doctor steps outside to cast his eye over the noisy neighbours. A brief exchange of looks, but the party goes on.

Jeff forces Cecilie into another embrace. (And after the flashback, we cannot but see history wish to repeat itself.) She laughs off his demand for a kiss, for love, his threat of suicide. “Don’t be so melodramatic”, she says. She wishes life—the film itself—to remain a comedy, not a drama.

On the floor, men sit and shoot dice. The band stop playing to peer at the heap of money. “Bal” deliberately shows up the band by betting a thousand dollars—and winning. (The sax player, looking down at the paltry coins in his hand, goes away comically disgusted—but disgusted is how we begin to feel by the crowd of rich white men flaunting their money in the foreground. Cecilie joins the betting, wings a thousand, them loses two thousand to Ballard. She bets him ten thousand, rolls—loses, bets forty thousand. She drinks. (And Jeff takes out a gun, head pressed to the wall.) Cecilie strips off her jewellery. She looks utterly lost. She bets her house—and loses.

Ballard seizes his slimy chance: “You could have it all back—if you wanted to…” The unspoken words are horrible. The look on Cecilie’s face says it all. She drinks, then crushes the glass in her hand. It’s an astonishing moment. Blood falls down her hand, wrist, arm. The imagery returns us to a kind of primal violation, relived before the man who would violate her again. The doctor is called for.

Van Martyn attends. Cecilie tries not to cry as he examines and treats her hand. He bathes it, examines it. “Is there a woman in the house?” “Only Circe’s beasts.” “I only ask you because I’m afraid I’m going to hurt you.” “I’m used to it, you don’t have to worry at all.” (The close-ups of Murray are remarkable, for she is remarkable here. A kind of complexity, strength, and vulnerability all in one.) Jeff looks on jealously from across the room, but the editing gives Cecilie and the doctor their own space.

Cecilie smokes her way calmly through the surgery. But she is shaking by the time it’s over, and vulnerable again when the doctor places her arm in a sling. To spite his advice for rest, she drains a cocktail glass and launches herself into a dance with a young man. Jeff is furious and grabs her. Ballard reminds him that everything here now belongs to him. Including Cecilie, he implies. Jeff calls him depraved, Ballard punches him, Jeff shoots—and misses. The doctor disarms him, but the party ends in a fight and Cecilie flees into the garden. “If that man had been killed, you would have been morally responsible”, the doctor tells her in passing.

Chez Van Martyn, he looks at the photo of the woman on his desk. But Cecilie follows. “How is it my fault if people behave like that?” He claims she appeals to their basest instincts. “Women like you ruin everything they touch”, he says. It’s a cruel, nasty thing to say. And we see how cruel and how nasty it is on Cecilie’s face, how unjust and uncaring. “What do you and women like you know about love?” he asks. She glances up and away, as if to an unseen audience. She is about to reply, but there is clearly too much to say—and rushes away. “The word love on your lips profanes what is most sacred”, the doctor goes on, piling cruel words on top of cruel words. She runs back, desperate, and falls to her knees to kiss his hand. The doctor turns, and its his turn to look vulnerable. He takes a step towards her, and in so doing crushes the picture of the woman underfoot. He stops. Cecilie goes back inside. Ballard grabs her, accuses her of being in love with the doctor. She calls them all animals and rushes away.

The doctor cannot sleep. He trues “to chase away the image of the woman who has revealed her soul to him”. A vision of Cecilie in a garden, an absurd child panpiper in the background. Cecilie in slow-motion, draped in diaphanous gown, dancing below willow branches. (Can I forgive the film this scene? Perhaps.)

The next morning and Cecilie has left, asking for all her possessions to be sold. The doctor arrives to find that no-one knows where she has gone. Meanwhile, Cecilie “instinctively returns to the locations of her childhood”. We see her enter the convent, go to church, and try to pray away her love. Later, we see her surrounded by the faces of young girls. She is teaching them, and trying not to cry. When one of the girls runs away through the gate, Cecilie chases after her—and is hit by a car.

Paralysed, she awaits surgery. While the doctor plays fetch with his dog, the dog ends up finding Cecilie’s diary in his former neighbour’s garden. He reads of her former life with the nuns in New Orleans. There, the surgeon feels they must try to make her walk. They get her to her feet, but she falls. Van Martyn arrives. She sees him. “Come to me, my beloved”, he says—and she stumbles her way across the room into his arms. (I wanted the camera to track in towards them, but the shot is held in dreadful suspense.) Her footsteps here are a kind of inversion of her dancing earlier in the film, a solo number more akin to ballet. It’s a gentler, more vulnerable kind of dance that brings her into her lover’s embrace. “Am I dreaming—or am I really in your arms?” The End.

Day 7: Summary

A curious programme today. I enjoyed the first film, but so little of the 9.5mm footage came from the silent era that I felt a little short-changed. As much as I love and am fascinated by obscure silent footage, it’s the era itself that fascinates in conjunction with the fact of its silence. Couldn’t we have had a film either entirely devoted to the earliest 9.5mm footage, or else skipped 9½ entirely for a different silent feature? I can appreciate that at the live Pordenone, this little film might have made a nice shift in emphasis. But online, with a much more limited programme and schedule, I feel I would rather have substituted it for something else. But still, an interesting watch.

As for Circe the Enchantress, it’s beautifully photographed, wonderfully performed, and surprisingly moving. Yes, the last scenes teeter on the edge of absurdity. It needed a director like Borzage to make this “miracle” truly miraculous. (See my piece last year on The Lady (1925) for another “wronged woman” narrative that ends with a kind of leap of faith.) But even if Circe the Enchantress is no masterpiece, I was invested enough to be moved, and found myself swept up in it. Much of this is due to Mae Murray, who exudes emotion—and when her eyes catch the camera, just for an instant, we see her at her most vulnerable, her most intense, her most revelatory. It’s a performance to challenge anyone’s view that the “woman with the bee-stung lips” didn’t have great talent. And I must also praise Donald Sosin’s excellent piano score (with occasional jazz band additions), which likewise played a large part in grabbing me by the heart: the music was sympathetic, tuneful, playful, and romantic in all the right ways at all the right moments. A hugely enjoyable film.

Paul Cuff