It’s the final day of the online festival—or at least it was, since I write this four days after it actually ended. But a bout of Covid has sent me to bed for the last three, so I’ve fallen behind my writing schedule. Now I have the strength to stand up and type, I can return to finish off my report of the final two films: first, a defining work of the German “street film” genre; second, a sensitive drama from William C. DeMille about the lure of the past…

Die Straße (1923; Ger.; Karl Grune)

“The film of one night”. The characters have no names. They are simply: the Husband (Eugen Klöpfer), the Wife (Lucie Höflich), the Provincial Gentleman (Leonhard Haskel), the Girl (Aud Egede Nissen), the Fellow (Hans Traunter), the Blind Man (Max Schreck), the Blind Man’s Son (Anton Edthofer), the Child (Sascha).

The story is very simple: the Husband is bored at home and goes out to explore the oponymous “street”. He ends up being lured into a nightclub by a woman, who—with her pimp/partners—lures him into gambling with an out-of-towner. The latter is then killed and the Husband falsely accused, only to be released just before he hangs himself from shame. He returns home to the embrace of his wife.

The story is a familiar one of (male) temptation, guilt, and return. But it’s the atmosphere of the film that takes hold of you. At the start, we see the Husband lying snoozing on the sofa. The Wife cooks, clears the table. Lights and shadows play upon the ceiling. The Husband gazes up, half asleep. An astonishing vision projected above him: a man and woman walk, stop, interact. The Husband goes over to the window to stare at the world outside. A flowing montage of sights, multiple superimpositions of life on the streets. He sees fireworks and clowns and parties teeming and swarming. Then the Wife goes to the window. Another close-up, followed by her view: a single, unmanipulated view of the street—ordinary life, going about its business. She puts the humble dinner upon the table. The man, repulsed by the interior, rushes outside.

Everything is set up here: the subjectivity of the nightlife, the explicitness of male fantasy and female subjugation. In the first scene in the street, the Husband encounters a streetwalker. She pauses. He stares. Her face becomes a skull. (Shades of ancient imagery, of ancient associations: strange women, prostitutes, disease, death.)

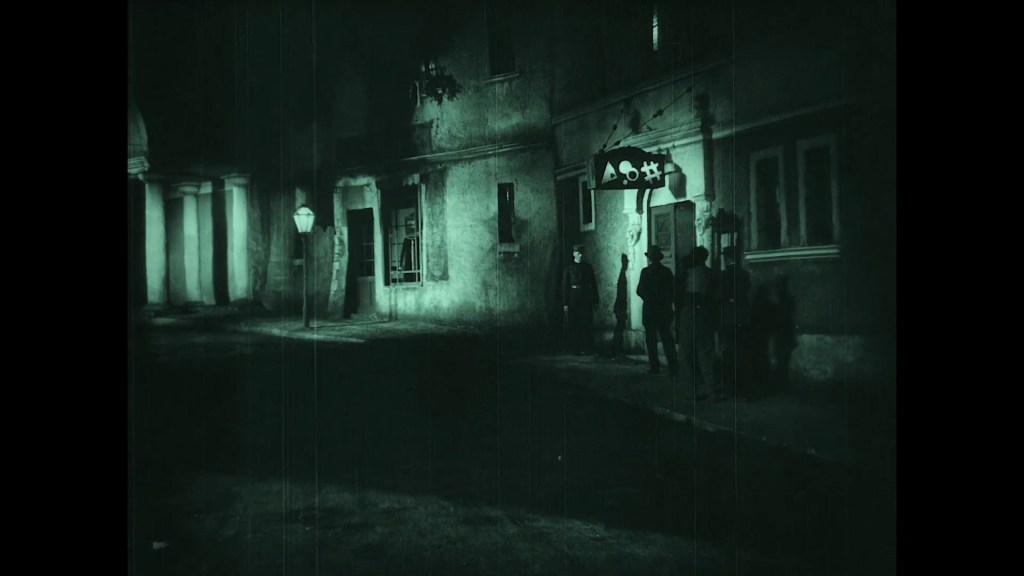

This vision warns us that the world on screen will be dreamlike rather than realistic. Everything is subtly heightened, warped. When the Blind Man and the Child (his granddaughter) leave their tiny apartment, we see the interiors’ subtle disfiguration by design and by shadow. Expressionism leans on the uprights, exaggerates the hallways, the corridors. Outside, the streets are swathed in rich shadows and patches of light. There are also surreal interventions of the modern world: the Husband is entranced by an illuminated sign in the pavement, and later an opticians’ advert illuminates a pair of giant eyes in glasses that makes him flinch with guilt. When he follows the Girl to a park bench, we are given a view overlooking the city. But “the city” is a remarkable combination of models and paintings that has a dreamlike sensibility.

The camerawork heightens this atmosphere. When the Blind Man is separated from the Child, Grune places the camera at ground-level to capture the rhythm of the traffic pulsing dangerously around the child. And in the nightclub, the Husband becomes hallucinates the room spinning—and we then seen him, a dark silhouette, against the spinning vision we have just seen. And when he later bets his wedding ting, we see a vision of his wife (quite literally) slipping out of his life in a superimposed vignette framed by the ring in extreme close-up.

The heightened performance style—the slowness of gestures, the elaborateness of movement—are also all part of the dreamlike quality. We see the Husband’s journey from respectability to crime in the way he moves: his face slowly contorts with desire, with fear, with lust, with guilt, with triumph. Other figures are also more evidently characterized through costume and make-up. The Provincial Gentleman has his slightly shiny suit, his elaborate combover, his permanently shadowed cheeks—lined with age and/or flushed with colour.

But what all of this does is make you feel like you’re trapped inside a bad dream. For a start, the film eschews any geographical particularity. This “street” could be any street in any city. The signs we see (a distant street sign, the police station sign) are abstract symbols in no recognizable language. The use of models and false perspectives is subtle but all-prevalent. Reality is as absent as daylight. It’s a twilight world of neon night or pale dawn. In this world, the plot of the Husband’s downward descent feels as inevitable as it does nightmarish: things just keep getting worse and worse. Following his desire into the nightclub, he soon gets into a scuffle with the grotesque Provincial Gentleman over the Girl. Even when this is resolved, he’s drawn back into the Provincial’s company through the gambling table, where he bets, loses, bets again… bets a last cheque, and loses—only to reveal that that cheque was not his. Klöpfer’s performance makes you feel the gathering sense of doom like an oncoming panic attack. It’s a nightmare of repeated failure, of repeated mistakes, of satisfaction endlessly delayed.

Success in this world is also guilty. The Husband eventually bets his wedding ring… and wins… and wins again… and again… until he retrieves his money, his cheque, and leaves. Flush and giddy with success, he leaves—but is tailed by the Blind Man’s Son and the Fellow. (Another trip through snister streets, pools of light, deep shadow.) Even when he is about to “get” the Girl, he is being used by the gang to cover their crime. The Blind Man’s Son and the Fellow attack and kill the rich Provincial Gentleman while the Husband is next door with the Girl. The police end up intervening, arresting the only stranger now left on the premises: the Husband. At the station the Girl accuses him of the murder, her outstretched arm of accusation some kind of archetypal gesture, which can condemn even the innocent. (And, as in a bad dream, the innocent Husband is indeed condemned.)

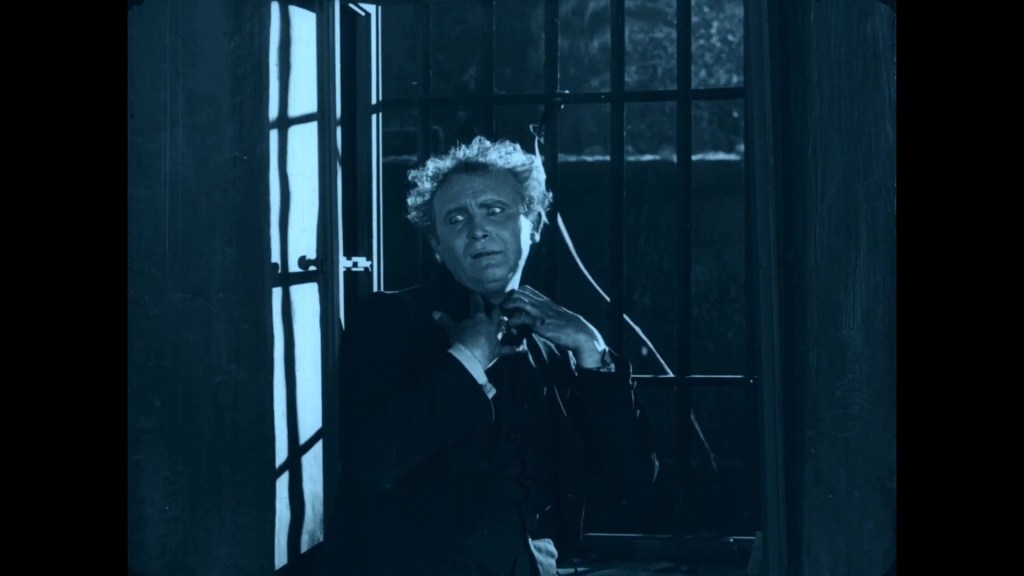

Does the ending offer us comfort? The Child eventually correctly identifies her own father as the murderer. The Husband is about to kill himself in his cell when the police arrive to release him. The image of his belt tied to the window grate, flapping in the wind, is extraordinarily chilling. It’s another image struck from nightmares. There follows a vision of the street by early morning: deserted but for sheets of newspaper blowing in the wind. The Husband comes home. His Wife is asleep at the table. Shamefaced, head bowed, he stands at the threshold. She takes the remainder of the dinner and places it upon the table. He goes to her, places his head on her shoulder. She strokes his head. They look at one another eye to eye. Ende. It’s an ending of ambiguity, of unanswered questions. What happens next? What does the husband say? Has his nightmare even ended?

Conrad in Quest of His Youth (1920; US; William C. DeMille)

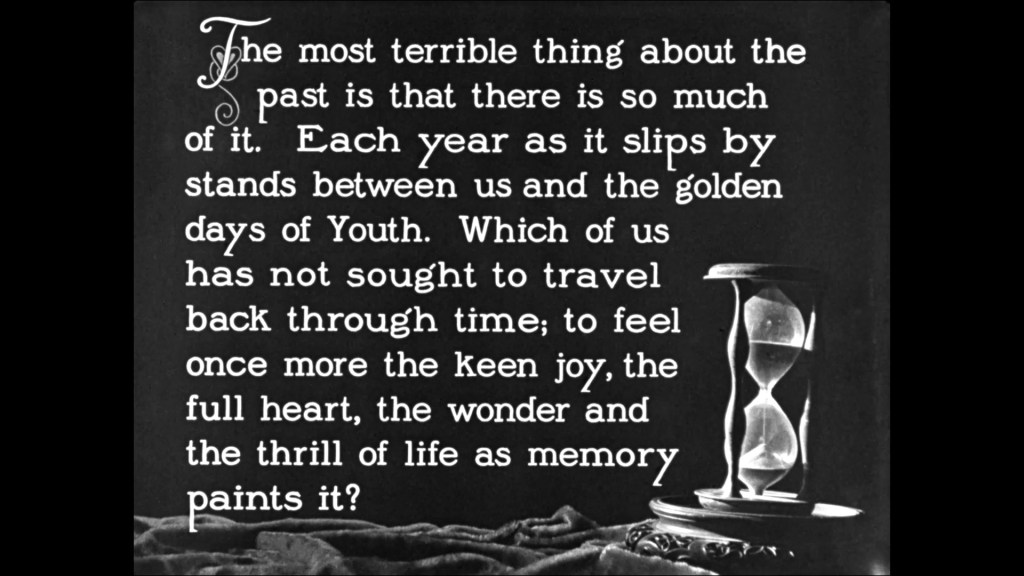

“The most terrible thing about the past is that there is so much of it…” Have we not all wanted to “travel back though time”? Here is Conrad Warrener, back from India, back from the Great War. The only one at home is Dobson, his servant. The simple delights of being home: a bath, fresh soap. Conrad mourns the loss of his fallen friends and wonders why he feels “like a stranger in his old haunts”. He goes through some old photographs. A picture of childish happiness: “Sweetbay”, and three other childhood friends. Ted, Nina, Gina.

They arrive. A mechanical music box is played. Old pictures on the wall, needlework. It’s all conspicuously a world from another century. Ted finds his old catapult, but it snaps as soon as he tries it. Dinner time, and the friends stare at the tiny table and chairs where they used to eat together. (Neil Brand’s piano accompaniment brilliantly brings back the theme used for the mechanical music.) Only Conrad likes the childhood fare of milk and porridge, but the women look disconsolate—and Ted slips some spirit into his mug to get through the meal. And instead of a game of bridge, Conrad insists on a boardgame. But the foul weather soon intervenes, blowing smoke back down the chimney.

That night, the comforts are hardly any better: water leaks though the ceiling onto the bed the women must share, while Ted’s bed is cracked and uncomfortable. While Conrad and Dobson play a boardgame, the three other guests huddle together and make plans to head back onto town the next day. All three have colds, and announce (with delightfully cold-inflected text) that they’re off.

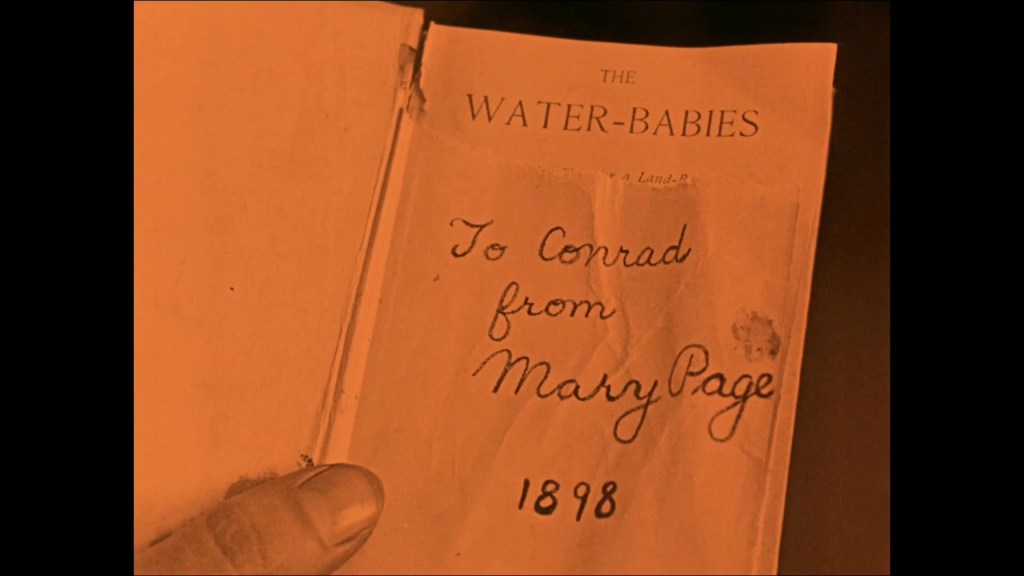

But Conrad picks up a book, dedicated: “To Conrad, from Mary Page, 1898”—and he seeks out his first love. She is now “Mrs Barchester-Bailey”, a conspicuously middle-aged woman with four boisterous children and a jealous husband, and ghastly soft furnishings.

So Conrad returns to London, seeking pleasure in the high life. At a table, he sniffs a bouquet: “And in the scent of the little white flower, Conrad is wept breathless across the years to a garden in Italy, when he was seventeen and madly in love with ‘the most beautiful woman in the world’. Mrs Adaile…”. (Dissolves, for once, make the transition between past and present, titles and action. It’s a kind of softening of the film’s thus-far conventional language.) He recalls his last night there, and the flowers she gave him—and the solitary kiss of her feeling. The last transition, the slow dissolve between the lonely youth and the present-day adult, is gorgeous.

Conrad returns to Italy, to the same location, and sees Mrs Adaile—now say knitting in the sun. But she cannot remember him. So he offers her the same flowers, pressed carefully into his wallet, and finally she recalls. “Conrad, my friend, you’re in love with a memory and not with me.” But both are invested in the fantasy, both trying to be young through one another. Their last night in Italy. A kiss given, an appointment made for that night for a final farewell. Dobson is ushered out, Adaile is busy powdering her face. Conrad reads a book to pass the time, and this is how Adaile finds him: asleep in a chair, book on his lap. She immediately has second thoughts, so writes him a note and pins it to his chair. Half-crying, half-laughing, she leaves. The next morning, he finds the note: “Farewell! There is no road back to seventeen.” Conrad heads home.

Enter Rosalind Heath, the widowed Countess of Darlington (and former dancer), who is likewise listless with her life. She too now goes through old photos, finds old letters from friends. But a bad train connection intervenes. Rosalind is visiting Tattie and her tiny theatre troupe. Rosalind and Conrad meet outside the theatre, where news has come that the manage has absconded with their money. Conrad offers to help, by now feeling he’s older than he actually is—and highly protective of Tattie and (in particular) Rosalind. He falls for her and she for him. After refusing his money, Rosalind accepts his proposal—but insists he ask “Lady Darlington” first. Of course, she is Lady Darlington. He proposes a second time, and the pair find happiness. The End.

A subtle, sensitive film. I liked it without loving it. The first thing that comes to mind after seeing it is that I can think of few other silent films in which scent is so thematically important. Conrad sniffs the soap at home, sniffs the flowers that send him back to Italy; Rosalind too, sniffs the objects of her youth: the cards, the grease paint. Food and drink, too, are used to try and summon or recreate the past. It’s a film very sensitive to all these sensory aspects. Yet the language of the film is never quite as lyrical or inventive as the extrasensory elements might suggest. The camera scarcely moves—most of the travelling between places or times is done through cutting. But the few instances when dissolves are used make them all the more potent, and I would love to have seen more use of these devices.

And if the film isn’t in any sense “showy”, it is still lovely to look at: the print is (aside from a few momentary sections of decay) in very good condition and tinted to fine effect. The photography is clear, sharp, and William DeMille shows us everything we need to know in order to grasp what’s going on. Besides, the drama is character-driven and therefore performance-driven. The camera doesn’t need to spell out emotions when the performers do so much. (Though the intertitles also do quite a lot of work.) And the cast is uniformly excellent. The film isn’t afraid to show us or talk to us about age and ageing, about regret and loss, and the performers all have moments of vulnerability shared with the camera. There is real emotion at the edge of every scene, and if there is no great melodramatic outpouring then that is because the film isn’t interested in wallowing in sentiment. It’s about ordinary characters experiencing feelings everyone knows and shares.

Day 8: Summary

A curious pairing of films in which (to find a common theme) men go out in search of something they don’t feel they have at home. Grune’s film is a far richer cinematic world, and a far more potent one. It makes you feel uncomfortable from beginning to end. It’s a fantastic piece of expressionism, where everything is heightened and meaningful. If anything, I was glad to emerge into the daylight world of Conrad in Quest of His Youth. DeMille’s film is less stylistically rich, but offers a wholly different range of emotions. It’s a real world, populated by real people. (Albeit the lead pair are ultimately cocooned from too much trouble by their wealth.) It’s subtle, tender, gentle. But I kept waiting to be really moved, and never was. And isn’t it a problem that the relationship presented in the past (with Adaile) moved me more than the relationship pursued in the present (with Rosalind)?

Tomorrow, I will try and gather my thoughts on the online festival as a whole and post a round-up of Pordenone 2023. Right now, I must go and lie down again—and hope my dreams are not unduly infected by the nightmarish atmosphere of Die Straße…

Paul Cuff

One thought on “Pordenone from afar (2023, Day 8)”