This is my third piece devoted to Die Wunderbare Lüge der Nina Petrowna (1929). Having previously talked about the beauties of this production and about its contemporary novelization, this week I discuss the scores created for the film’s exhibition in Berlin, Paris, and London in 1929-30.

The film premiered at the Ufa-Palast am Zoo in Berlin, in April 1929. The music for this event was arranged by Willy Schmidt-Gentner, a prolific composer of scores during the silent era – and beyond. He entered the industry after the Great War, initially working as a kind of tax inspector for cinemas. But he was also a trained musician, having studied with Max Reger in his youth, and eventually switched from film admin to film accompaniment. He gained experience acting as a conductor for cinema orchestras, as well as accompanying films at the piano. In 1922, he was commissioned to write his first film score – for Manfred Noa’s Nathan der Weise. He had clearly found his métier. Across the rest of the decade, Schmidt-Gentner created, adapted, compiled, and conducted nearly a hundred scores for silent films released in Germany. He was clearly both very versatile and very efficient at what he did: working fast was a key attribute to any composer in his position. The majority of his scores would doubtless have been compilations, drawing on various libraries of repertory music, as well as the latest popular melodies. By 1929 Schmidt-Gentner was Ufa’s chief arranger and his work accompanied many of their most prestigious productions – which included Nina Petrowna. Sadly, his score for this film has either been lost or else lingers in limbo somewhere in the archives. I say “archives”, but I have no idea what archives might be responsible. Of all Schmidt-Gentner’s scores, I am not sure any have been fully restored for modern performance. I am unsure, in the most literal sense, where his music has gone!

Thankfully, there are many detailed press reports of the premiere of Nina Petrowna, so we can glean some sense of what it was like. Before the film began, the first movement of Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto (1878) was played as an overture. (We even know the soloist who performed this piece at the film’s premiere: Andreas Weißgerber. Weißgerber was a popular concert violinist, so a notable a guest performer for Ufa’s concert.) Presumably much of the score itself was likewise music compiled from existing sources, though the reviews do not make this clear. For the opening cavalry parade, we are told that the orchestral march involved the use of a small group of musicians hidden behind the screen/in the wings. When the cavalry marched past, the music was initially performed by these hidden players; then, as the film showed the cavalry more closely, the main orchestra took up the music. For the scenes around the barracks and military club, various quick “Russian” marches were used, while elegant waltzes characterized the scenes at the “Aquarium” club. Though some reviewers accused Schmidt-Gentner of being heavy-handed (and sometimes simply too loud!), his score for Nina Petrowna used chamber sonorities for the lovers’ scenes: a string quartet with celesta accompanied their meeting in the club, for example. The one piece of original music we know to have been used in the film was for Nina’s favourite waltz, which is described as a melancholy “valse Boston” – the melody of which recurred throughout the film as a kind of leitmotif.

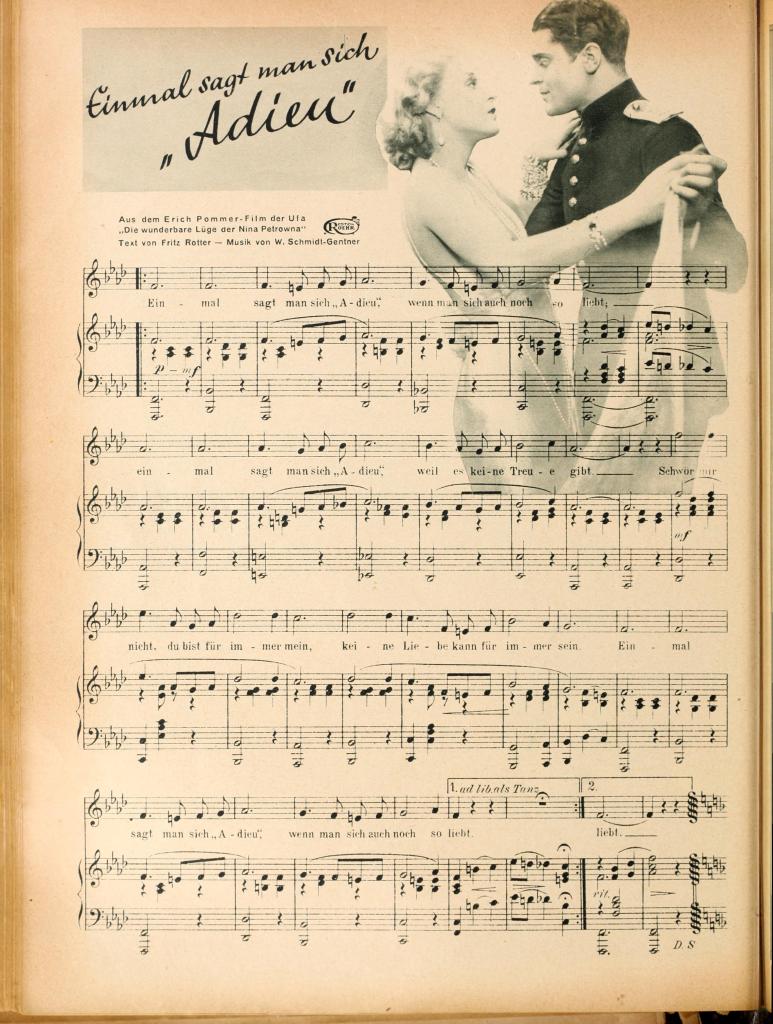

This waltz is the one part of the score does survive – thanks, in part, to Ufa’s own marketing campaign. Schmidt-Gentner’s melody was initially referred to as “Die Stunden, die nicht weiderkehren”, but for commercial purposes it was given words by Fritz Rotter and became the song “Einmal sagt man sich ‘Adieu’”. The main lyrics are:

Einmal sagt man sich ‘adieu’, / Wenn man sich auch noch so liebt. / Einmal sagt man sich ‘adieu’, / weil es keine Treue giebt. / Schwör mir nicht: du bist auf ewig mein. / Keine Liebe kann für immer sein. / Einmal sagt man sich ‘adieu’, / Wenn man sich auch noch so liebt.

A crude translation of this might be:

One day we’ll say goodbye to each other, / No matter how much we love each other. / At some point we’ll say goodbye to each other, / Because there’s no such thing as fidelity. / Don’t swear that you are mine forever. / No love can last forever. / One day we’ll say goodbye to each other, / No matter how much we love each other.

Note the German use of “man”, i.e. the third person singular, which might refer to oneself or to a slightly more abstract/general “we”. The song might therefore be a personal narrative or else a more general one. Its address sits interestingly between the personal and impersonal, as well as between tenses. It uses the present tense, but the “Einmal” (literally, “one time” – or even “at some point”/“eventually”) also suggests that it might refer to future events. (In German, the present tense can also express the future when combined with a time element.) All of which is to say that it has a tone that might apply to any listener, anywhere – that, and the gorgeous melancholy of the melody, ensured that the song was a hit success. Even if Schmidt-Gentner’s score was not performed widely outside Berlin cinemas (and it is unclear to what extent the score was distributed with the film for its silent release), the song ensured that its main original theme could circulate widely.

Another reason for the survival of this part of Schmidt-Gentner’s silent score is, ironically, the coming of sound. Ufa was already in the process of converting its major productions to sound, and Nina Petrowna was subsequently reissued with a recorded music-and-effects track in 1930. (I am unsure whether any copies of this version survive. Certainly, I can find no archival holdings on publicly accessible databases.) But even for its initial release in silent format, Ufa’s publicity marketed the film in relation to its theme song. In 1929-30, several recordings were made to capitalize on the popular success of the film – and presumably to help sell its initial release in cinemas. These vinyl releases featured contemporary bands like Dajos Béla’s Tanz-Orchester or popular singers like Wagnerian tenor Franz Völker and the ubiquitous Richard Tauber (famous for his roles in Lehár operettas). The speed at which such recordings could be licensed and made is impressive. The Derby company, for example, got the “Karkoff-Orchester” (their own scratch band) to record an orchestral arrangement of the waltz, which was released in May 1929, when the film was in the first month of its general release. More broadly, these discs point to the changing context for the marketing and consumption of film music. Before Ufa had even released its first talkie, the company’s silent pictures were already being sold in relation to recorded sound. On one level, the strategy clearly worked: the sheer number of recordings spawned by “Einmal sagt man sich ‘Adieu’” (always credited on discs to Ufa’s film) indicates a popular hit. Indeed, the song continued to generate recordings throughout the twentieth century and even into the twenty-first. (For example, Aglaja Camphausen’s recent rendition is particularly lovely.)

Nina Petrowna was one of Germany’s biggest commercial hits of the 1928-29 season, and Schmidt-Gentner’s score received very good reviews at the time of the premiere. Given this success, it is ironic that the music now most associated with Nina Petrowna was written by the French composer Maurice Jaubert. This orchestral score accompanied the film’s “exclusive” run at the Salle Marivaux in Paris, from 25 August 1929. Jaubert had already worked as an arranger, compiling selections from the works of Offenbach to accompany Jean Renoir’s Nana (1926) at the Moulin Rouge theatre in Paris. Jaubert subsequently prepared the perforated music rolls of Jean Grémillon’s mechanical piano score for his documentary Tour au large (1927, lost). His music for Nina Petrowna thus represents his first original film score, though it should be noted that it is not entirely his own work. Jaubert also relied on musical collaboration: some scenes were scored by Jacques Brillouin and Marcel Delannoy, while another recurring theme is taken from Erik Satie’s “De l’enfance de Pantagruel” (the first number of Trois petites pièces montées (1920)). Brillouin and Delannoy had compiled the orchestral score that accompanied Grémillon’s Maldone (1928), which included music written by Jaubert.

As I wrote in my earlier piece on the film, Jaubert’s music is superb. Though Schmidt-Gentner’s score was written for a large symphony orchestra, and Jaubert’s for a chamber orchestra, they share several qualities: both make use of lighter sonorities and a central waltz motif that recurs throughout the film. Schmidt-Gentner’s music seemed to have relied on a more “Russian” milieu, though his waltz was a “Boston” – and thus another kind of popular cultural import. (The contemporary recordings make the waltz sound very much part of the soundworld of the 1920s dancehall rather than pre-war Russian.) Jaubert’s music, however, is superbly attuned to the mood and rhythm of the film. The flowing camerawork and long takes aid the ease with which the music seems to glide along with the film. But even though Jaubert uses slower tempi and extended passages (complete with repeats), he knows when to match key moments. Important sounds on screen, for example, are matched in the orchestra. Listen to the exquisite way Jaubert turns the chiming clock into music—high strings, piano, percussion—in a way that interrupts the waltz theme, but also sends us (tonally) somewhere oddly private and dreamy. (This melody has to be both memorable and moving, since it recurs in the film in vital scenes of union and separation for the central couple.) Or the lovely scene when the pianist in the orchestra must synchronize to the incompetent Michael’s efforts at the piano on screen. But the most dramatic is when the orchestra suddenly falls silent at the dramatic revelation in the final scene.

Given its importance in the history of Jaubert’s career, it is surprising that I haven’t been able to find any contemporary French reviews of Nina Petrowna that mention his name. I have found an advertisement for the film in the French press of the time, which marketed its exhibition with explicit reference to live music: “You will hear the best orchestra and you will see Brigitte Helm in…” (see image below). The same page is littered with adverts for sound films and synchronized scores, suggesting something of the climate in which Nina Petrowna was released. (Three months after the live exhibition of Nina Petrowna with “the best orchestra”, the Salle Marivaux premiered André Hugon’s Les Trois masques (1929) – the first all-talking production made in France. No longer was a live orchestra required.)

This same context highlights the release of Nina Petrowna in the UK. The film was distributed under the title The Wonderful Lie, premiering in London in June 1929. This presentation opened a special run of silent films accompanied by a full orchestra at the London Hippodrome. The Wonderful Lie, and its specially arranged score by Louis Levy, got rave reviews. It was championed especially by critics who hated the influx of talkies, which was also how the film was advertised – as the swansong of silent cinema.

Like Schmidt-Gentner, Levy had been working as an arranger of cinema music since the 1910s and would have a prosperous career in later decades as the supervisor of numerous sound film scores. I can find very little information on the contents of Levy’s score for The Wonderful Lie. It was doubtless a work of compilation, likely drawing on a familiar repertoire of music. But there was also at least one piece of original music that was used, which has survived. This was the song “Nina”, with music by Cecil Rayners and words by Herbert James. I can find no evidence that Rayners’ “Nina” was performed with a vocal soloist during exhibition. As with Schmidt-Gentner’s “Einmal sagt man sich ‘adieu’”, the song more likely functioned as a way of promoting the film. An advertisement in The Era (10 July 1929), for example, offers “The Beautiful Theme Number in the New Film Production of ‘THE WONDERFUL LIE’ now showing at the London Hippodrome Song”. Interested parties could buy the theme as arranged for full orchestra, small orchestra, or piano. Was the song performed at screenings outside the London Hippodrome? And what other kinds of music were heard with the film around the UK? These questions could just as readily be asked of the film’s distribution in Germany and France – and the answers would be as numerous and varied as the landscape of exhibition practice at the time.

In summary, the scores of Schmidt-Gentner, Jaubert, and James offer an interesting case study of how music might differentiate the experience of a film across national contexts – as well as extend the life of a film beyond its cinematic exhibition. Though Schmidt-Gentner and Jaubert are important figures in film music of this period, their reputations are widely divergent. Jaubert is celebrated for his music for sound films of the 1930s, not to mention his early death on active service in 1940. His music has been recorded many times and his work is known outside France – and, I suspect, beyond specialist circles. Schmidt-Gentner may be a familiar name in Germany, and his melodies may still occasionally be heard, but his scores from the silent era have not received the same level of treatment; his musical legacy is thus highly restricted. This is perhaps one reason why it was Jaubert’s score for Nina Petrowna that was restored and recorded in the 1980s, not that of Schmidt-Gentner. That said, Jaubert’s score has not been heard since it was broadcast with the film on the Franco-German channel ARTE and on Swiss television in 2000. The same restored print that was broadcast that year was digitized by the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung in 2014 and shown in various venues, but never with Jaubert’s music. I can only hope that this beautiful film and score are one day reunited and released on Blu-ray. (If so, I bagsy doing the audio commentary!) Likewise, I hope that the score by Schmidt-Gentner one day resurfaces – together with more of the dozens and dozens of others he created in the silent era. Fingers crossed…

Paul Cuff