This week, I offer some very belated thoughts on a very significant Blu-ray. Lumière! Le cinématographe, 1895-1905 was released in 2015 to coincide with the 120th anniversary of the first cinema screening in 1895. Its original release having passed me by, my first effort to see it came only in 2022. By this point, the Blu-ray was long out-of-print, and I thought I had lost my chance. Even finding listings for it on retail sites is difficult. I had to search via a UPC/ISBN, which was itself tricky to find. It then took many weeks of waiting for an availability alert before I could even find a copy for sale and get hold of it. But I did, and it was worth it.

Lumière! Le cinématographe, 1895-1905 is an assemblage of 114 films made under the auspices of the Lumière brothers. I can hardly proceed without commenting on the difficulty of classifying this as an “assembly/assemblage”, a word that may or may not be any clearer than “film”, “video”, or “montage”. I choose “assemblage” because it seems the most pertinent (and works in French, too), though any of the above terms raise curious historical questions about presentation. Whatever we call it, the selection and editing (i.e. the montaging) of this collection was undertaken by Thierry Frémaux, director of the Lumière institute in Lyon, and Thomas Valette, a director of the Festival Lumière in Lyon. The original films are presented without any (recreated) text or titles, though an option on the disc allows you to turn on subtitles that identify the film, date, and camera operator (when known). There is also a commentary track by Frémaux, which contextualizes these films and offers insights into the history of their making and restoration. For my first viewing, I chose to do without any of these additional curatorial options, preferring simply to watch all the way through in purely imagistic terms.

The assemblage is divided into eleven chapters. These are thematic, grouping the films into miniature programmes that take us through various modes and subjects: “Au commencement”, “Lyon, ville des Lumière”, “Enfances”, “La France qui travaille”, “La France qui s’amuse”, “Paris 1900”, “Le monde tout proche”, “De la comédie!”, “Une siècle nouveau”, “Déjà le cinéma”, “A bientôt Lumière”. None of these chapters attempts to recreate an original film programme from the period. That said, the first chapter contains several films shown in that first projection on 28 December 1895: La Sortie de l’usine Lumière à Lyon (I), Arroseur et arrosé, Le Débarquement du congrès de photographie à Lyon, Repas de bébé.

The 2015 assemblage also recreates visually the effect of the original hand-turned projection. Thus the first film, La Sortie de l’usine Lumière (III), begins as a still image before flickering and juddering into motion. It is unexpected, and startling. It’s a great way to try and mimic the sense of shock and surprise of that first screening, of the instant that the still photograph literally seemed to come alive. From my distant days of teaching silent cinema, I know how difficult it is to get students to grasp the significance of these Lumière films as miraculous objects. This miraculousness seems to me an essential feature of their history, and therefore an essential quality to try and recreate in a classroom or any modern setting for their projection. If simply presenting the films as it appears on disc, without any curatorship (i.e. technological or performative intervention), the opening Lumière! is as good a way as any to reanimate La Sortie de l’usine Lumière à Lyon. (Though I find it curious that the 2015 assembly opens with the third version of this film, shot in August 1896, rather than the first, shot in May 1895. The third version is, as many have noted, a more carefully directed “view” than the first. The first version begins in medias res, with the workers already pouring out of the gates. The third version begins with the factory gates being opened.) I found it very moving to think about this sequence of images being watched by that small audience in Paris for the first time.

Part of the emotive effect was perhaps also due to the music chosen. This is the first time I can think I have ever seen these early films accompanied by an orchestra. The 2015 assembly uses various compositions by Camille Saint-Saëns, taken from his ballet Javotte (1896), together with his Rapsodie bretonne (1861, orch. 1891), Suite Algérienne (1880) (misidentified in the liner notes as the Suite in D major (1863)), and incidental music to Andromaque (1902). Though Saint-Saëns remains a very popular composer, much of the music used here is seldom heard. (As I write, I am listening to the only complete recording of Javotte, from 1996, a CD which has been out of print for some years. The 1993 recording used for Lumière! is a performance of the suite derived from the ballet.) The choice of Saint-Saëns is interesting. In many ways, Saint-Saëns is a perfect fit for the Lumière films. The composer’s reputation (for good or for worse) is for elegant, polished, well-crafted, well-mannered music. (“The only thing he lacks”, quipped Berlioz, “is inexperience.”) In photographs, Saint-Saëns even looks like he might have stepped out of a Lumière film. His build, his dress, his bearing – they all have the same air of bourgeois contentment as many of the films. (Even his fondness for holidays in French-controlled North Africa echo the touristic-colonial views in the Lumière catalogue.)

Differences in subject-matter and representations of class are a mainstay of scholarly comparisons between the Lumière films and those of Edison’s producers at the same period in the US. The latter tend to present (and perhaps be a part of) a scruffier, often more masculine, often more working-class world. Their glimpses into late nineteenth-century America present a very different social and physical world from the fin-de-siècle France of their counterparts. It’s somehow fitting, therefore, that Lumière! presents this latter world in the musical idiom of a composer who embodies the urbane, bourgeois sensibilities of the films.

If all this sounds like criticism, it isn’t meant to be. Put simply, a soundtrack of orchestral Saint-Saëns is a nice change to hear from the perennial solo piano accompaniment, which (in previous releases of this kind of material) tends to noodle along anonymously, hardly having anything to interact with on screen – and hardly any time to establish a musical narrative or melodic character. Yet the Saint-Saëns is not quite able to form longer narratives across a sequence of films in Lumière!. Very often, the directors feel obliged to match the sense of narrative excitement or visual climax on screen. This means some awkward editing of the music, together with a good deal of repetition of the same passages. As editors of the soundtrack, they react like the cameramen of the 1890s, who might pause their cranking if there was a hiatus in the action before them (like sporting events) and then turn once more when the action resumed. And, of course, there are instances of cutting and splicing in some of the earliest films, demonstrating a sensitivity to the need to shape narratives even within the singular viewpoint of these one-minute films. So poor old Saint-Saëns has his music interrupted, spliced, and resumed to fit some (but not all) the notable events on screen. The awkwardness of this is interesting, since it demonstrates the problem of presenting such short, sometimes disparate cinematic material. I would have been curious to see a more careful arrangement of film and music, or even a total disregard for precise synchronization. As it is, the effort made to match the music to some of the action feels somewhat crude. This is not musical editing, as such, since reworking a score would be more effective than manipulating a pre-existing recording. A reworked score could be played through with conviction. A reworked soundtrack plays itself into a muddle.

Regardless of these minor reservations, Lumière! is still a unique opportunity to watch these pioneering films. Unique because this Blu-ray remains, as far as I am aware, the only home media release of so many Lumière films in high definition. As the liner notes explain, Louis Lumière was an exceedingly careful preserver of his family’s photographic legacy. While 80% of the entire output of the silent era has been lost, the Lumière catalogue survives in remarkably complete and remarkably well-preserved condition. The films in this assembly were scanned in 4K from the original sources and they look stunning.

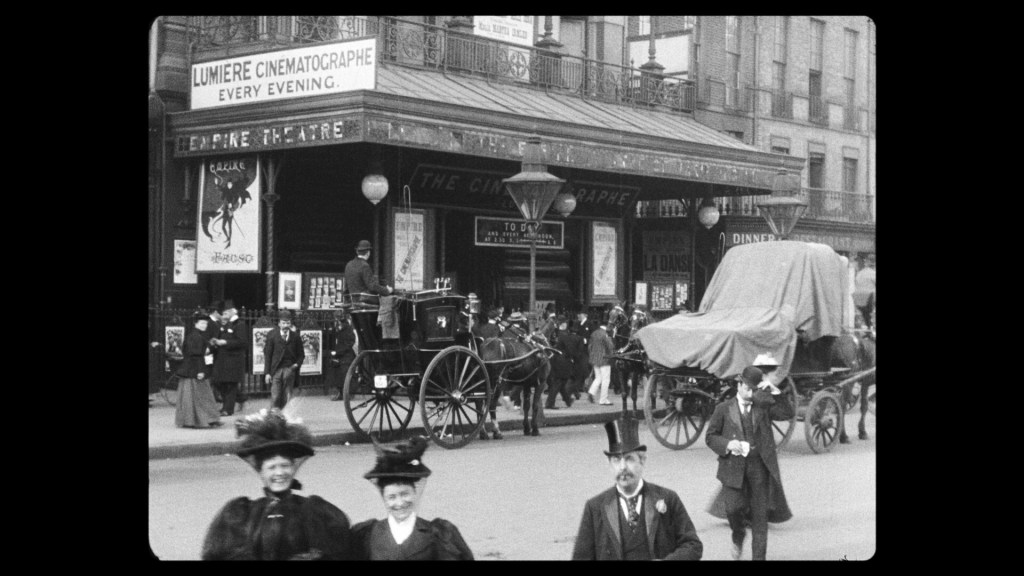

What I love about the Lumière films, and indeed about early cinema in general, is the chance to watch lost worlds go about their business on screen. There is something deeply fascinating, and deeply moving, about seeing into the past this way. It’s not just the tangible reality of the world on screen, it’s the fact that even the more performative elements themselves have an aura of reality about them. What I mean is that even the act of putting on a show for the camera is an act of history – a chance to see how the past played and cavorted and made itself silly for the amusement of its spectators. They’re not putting on a show for us, they’re putting on a show for their contemporaries – fellow, long-vanished ghosts. The audiences for these films are as lost to oblivion as those individuals captured on celluloid. That’s part of the reason why the sight of people eyeing up the camera, either by chance or by design, is so captivating. Their momentary involvement with the lens, with the operator, with the audience, has somehow escaped its time and survived into ours. Ephemeral views, ephemeral acts, ephemeral lives – all, miraculously, survive.

To talk about just one instance of this sensibility, I must single out La Petite fille et son chat (1900) – in which (as the title implies) a young girl is shown feeding (or attempting to feed) a cat. The girl is Madeleine Koehler (1895-1970), the niece of August and Louis Lumière, and Louis Lumière filmed the scene at the girl’s family home in Lyon. But to treat this film as historical evidence, or a kind of narrative content, is to miss something essential about its beauty. For although it demonstrates the ways in which a “view” might be constructed (the careful composition, the framing against the leafy background), and its narrative manipulated (the cat is encouraged/thrown back onto the table more than once, and the moments in-between later cut out), the film is dazzling in a more immediate sense. Though I have seen La Petite fille et son chat on a big screen before, I have never seen it in such high visual quality. The texture of the background grass and trees is deliciously poised between sharpness and distortion: you can almost reach out and touch the grass to the right of the girl, but even by the midground it becomes an impressionist mesh. In the centre of the image, the girl’s summer dress is so sharp you can virtually feel the creases. Light falls on her arm and legs, and when she looks up, she almost needs to squint against the bright sky somewhere behind us. Sometimes the girl catches our eye. She knows she is performing for the camera, for her uncle, perhaps for us – but she doesn’t quite know how. Poised between engagement with her world, with her cat, and with us, she is also poised between reality and fiction.

But, for me, the real object of beauty on screen is the cat. Just look at the texture of the cat’s long hair – the depth of its darks and the sheen of its highlights. See how the light catches its white whiskers, the shading and stripes about its face and eyes. There is a moment when the cat turns its back on the child to face someone, or something, behind the camera. For this fleeting second, the sun catches its eyes – illuminating one and shading the other. I’ve spent many hours of my life in the company of cats, and looking into their eyes up close is a peculiarly pleasing and intimate sensation. There is always the sense of otherness in those eyes, a tension between great intelligence and great unknowability. Even at their most proximate to us, the inner life of cats runs but parallel to ours. All of this is to try and make sense of just how moving I found watching La Petite fille et son chat in such high quality. The aliveness of this beautiful animal – the way it leaps, and turns, and reaches out with its paw – is extraordinary. This creature is long, long dead – yet it appears to us so animate.

One might say this about anything and everything we see in the canon of silent cinema. La Petite fille et son chat is just one short, evocative fragment of an immense photographic record. But the fact of its brevity enhances its potency. It is a worthwhile reminder that it is not just the people who populate the Lumière films that are lost to oblivion: animals are equally subject to erasure, and their lives are more fleeting and more unknowable than ours. Here, then, is an exceptional animal – these few seconds of its life, its body in movement, its intelligence in action, singled out and projected into the present. The miracle of the past, the miracle of cinema.

Paul Cuff