Not going to silent film festivals is becoming something of a habit, if not a hobby. In October I don’t go to Pordenone, and now in August I’ve begun not going to Bonn. As with Pordenone, the Stummfilmtage Bonn (aka the Bonn International Silent Film Festival) offers a “streamed” festival for viewers like me who, for various reasons, cannot attend in person. (I consider not going to Bonn a kind of pre-season training for not going to Pordenone.) Unlike Pordenone, however, the online content of the Bonn festival is free. Each film is available for 48 hours after each screening. No fees, no obligations – just a (quite generous) time limit. I aspire to one day having the kind of lifestyle that enables me to go to some, any, or all, of the wonderful festivals partially or wholly dedicated to silent film across the summer months – Bristol, Bologna, Bonn, Berlin (the “Ufa filmnächte”), Pordenone. But until this magical surfeit of time and budget is forthcoming, I shall remain at home, eagerly scrambling to fit in at least a couple of weeks’ worth of cinema into my free time. So, this week (or rather, last week) I’m not going to Bonn, and can share my experience of staying at home. First up, days one and two (and spoilers galore)…

Day 1: Du skal ære din hustru (1925; Den.; Carl Th. Dreyer)

I must admit that I considered not watching this film simply because I knew it well from previous viewings. (And have its BFI release on my shelf.) I further admit that if this film had been part of the streamed content of Pordenone (i.e. if I had to pay for it), I would have been annoyed that something so readily available should be chosen over something not otherwise accessible. It’s a film that I have seen before, but never on a big screen and never with live music. If I was actually at Bonn, I would be delighted to see it again – and to see it for the first time in such circumstances. I can understand why festivals put on films that are well-known or made by well-known filmmakers. But the appeal is much less for a viewer who is streaming the film remotely and not gaining anything new from the process.

That said, I still watched Du skal ære din hustru. I’d not seen it in years, possibly not even on Blu-ray. (The copy on my shelf is, now that I think about it, unwrapped.) So why not join in, however tepidly?

Do we all know the plot? Well, just to remind you: Viktor and Ida have been married for years, but Viktor is a domestic tyrant – ungrateful, unthinking, inconsiderate, rude, and subtly cruel. Despite their three children and former happy times, Ida is convinced by her mother and by the family’s old maid, Mads, to leave home. Mads plans to turn the tables on Viktor and make him realize how lucky he is, and how unjust he has been. Seeing the hardship of housekeeping firsthand, Viktor begins to realize his guilt – and eventually the couple are reunited on a firmer basis.

Of course, I was a fool to have thought of skipping this film: it’s a masterpiece. I’d forgotten how perfect it was. I fell all over again for the exquisite photography, those soft yet dark irises – like curtains around the frame, that distance the mid-shots of husband and wife. And I’d forgotten the first real close-up of Viktor, and the extraordinary depth of his eyes – and the way the light catches them and seems to magnify their life and feeling. This shot comes almost exactly halfway through the film, and I was unprepared for its power. So too, I was struck by the minimal number of moments when characters touch each other gently, with kindness. That close-up of the fingers of Viktor’s oldest daughter shyly reaching over to his, the way his respond – and you realize that he has a heart, and a past that was loving, and a future that might rekindle that love. An exquisite moment. So too the skill of rendering Mads teaching Viktor a “lesson” both funny and touching: the reversal of his cruelties, but also the desire to find his goodness. I’d forgotten, too, the embrace of Viktor and Ida: the way it’s a private moment, with Viktor’s back to us, and we see Ida’s hands move over his shoulders. Perfect.

By the end, I felt like Viktor: I had taken something for granted and was glad to be taught a lesson. You can and should always rewatch a great film. It has plenty still to teach you.

Day 2: Jûjiro (1928; Jap.; Teinosuke Kinugasa)

Right, now we’re back on track. A real rarity! Unavailable in any other format! Kinugasa’s film seems to have been released under multiple English-language titles. It’s listed variously as “Crossways”, “Crossroads”, and “Slums of Tokyo”. The dual German-English intertitles of this print gave the title as “In the Shadow of Yoshiwara”. There were no restoration credits to clarify the source of this print, which made me wonder about its provenance. There are evidently some missing titles, if not other material. (For example, one title announces “end of fourth act” despite no other “act” titles appearing in the print.) Furthermore, the English text is often awkward and rife with spelling errors. (The wording offers some very literal translations of the German text.) When and where was this print made?

This reservation aside, the film was excellent. The plot is simple, the drama concentrated – claustrophobic. In c.1850 Tokyo, a brother and sister live in a poor flat near Yoshiwara, the red-light district. The brother hangs out amid the frenzied atmosphere of gambling, stealing, and whoring. He is obsessed with O-Ume, who works in a brothel. He fights a rival for her affections, but the rival blinds him with ash. Believing he has killed his opponent, the blinded brother finds his way home. But the sister needs money to help him, so she is faced with selling herself either to her creepy neighbour or to the procuress of the brothel. The brother’s blindness is lifted in time to witness his sister stabbing the neighbour in self-defence. The pair flee to the city’s outskirts, but the brother is drawn back to O-Ume. He sees her with the rival he believed he had killed. His blindness returns; he collapses and dies in a fit of madness. END.

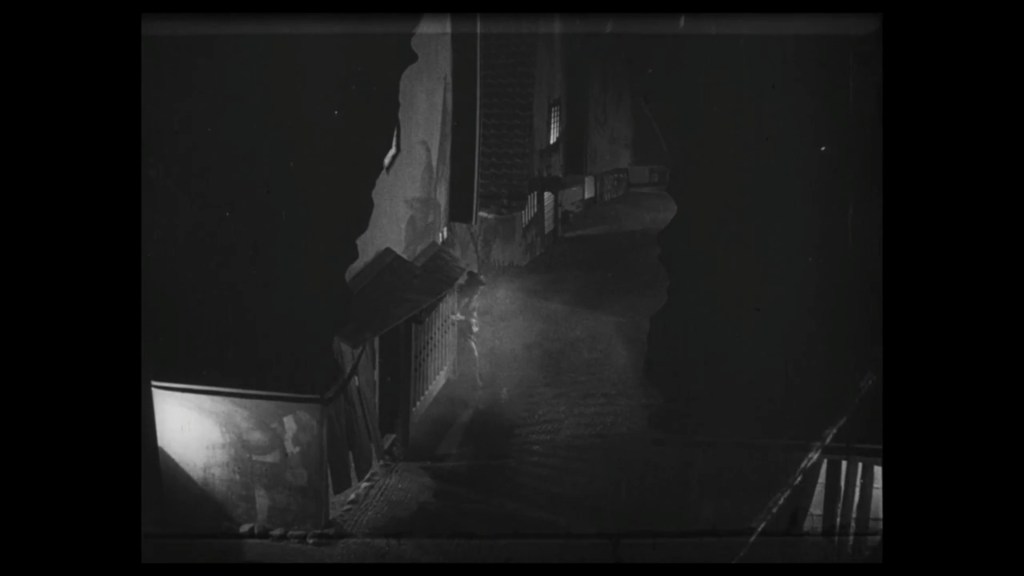

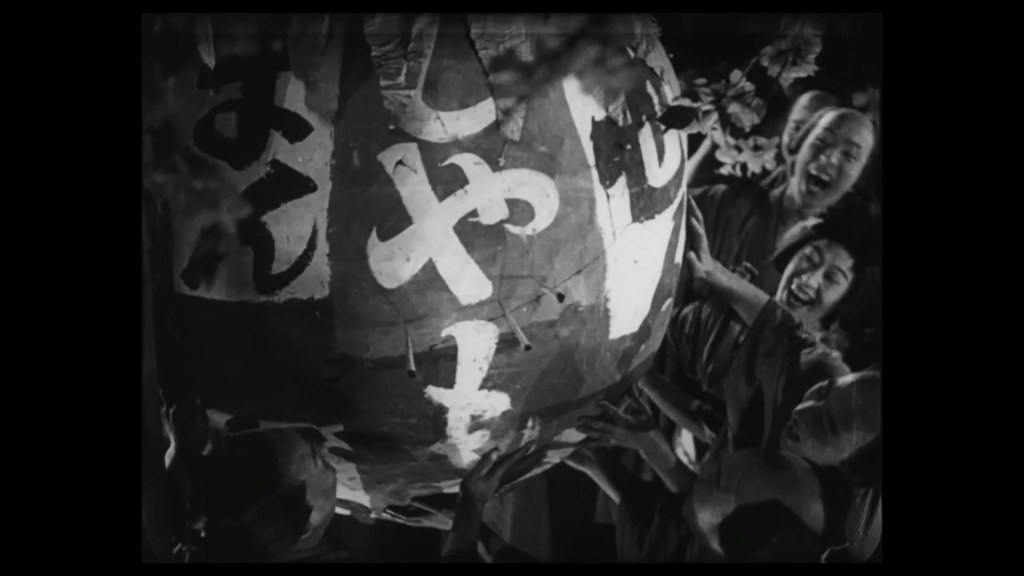

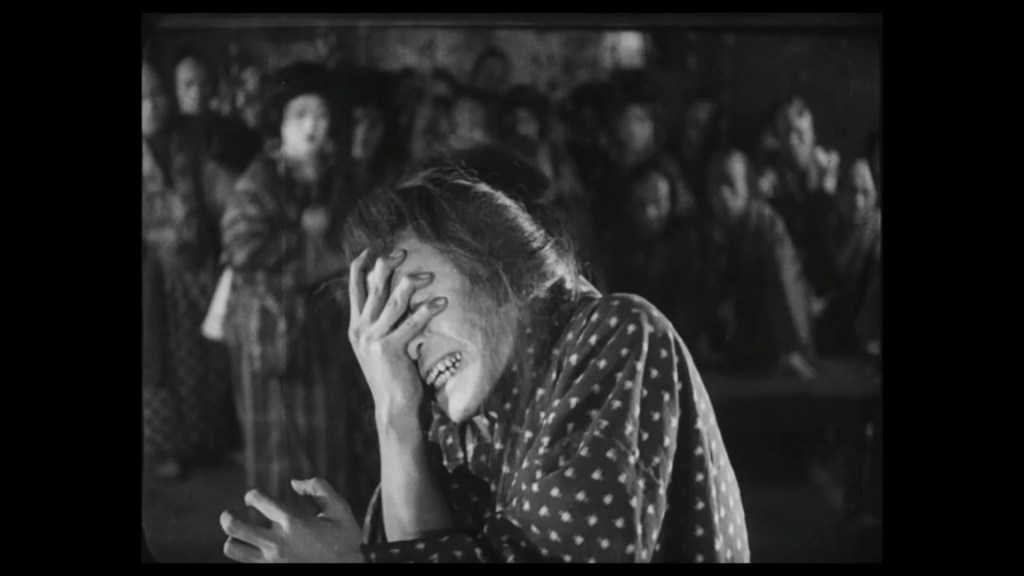

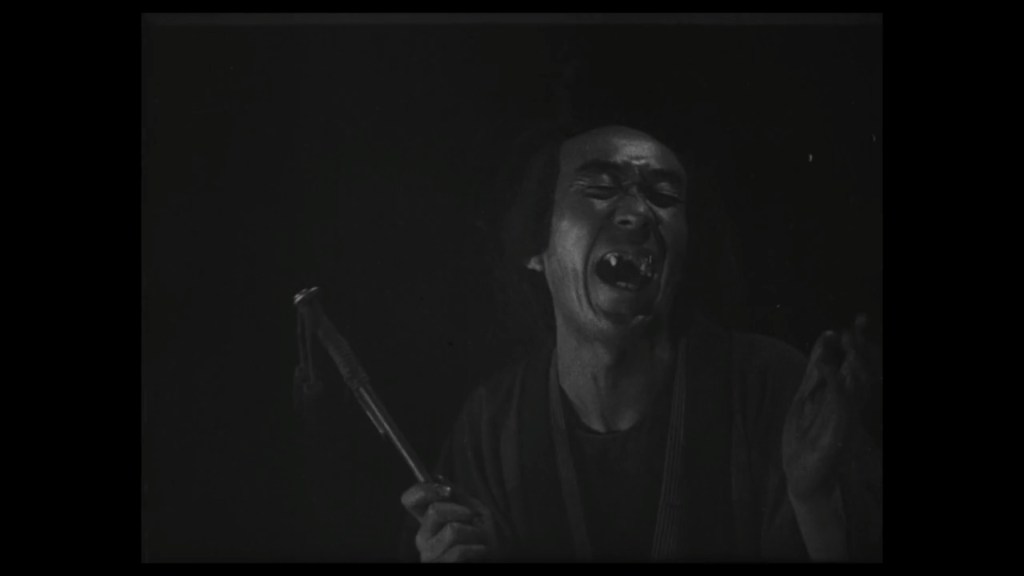

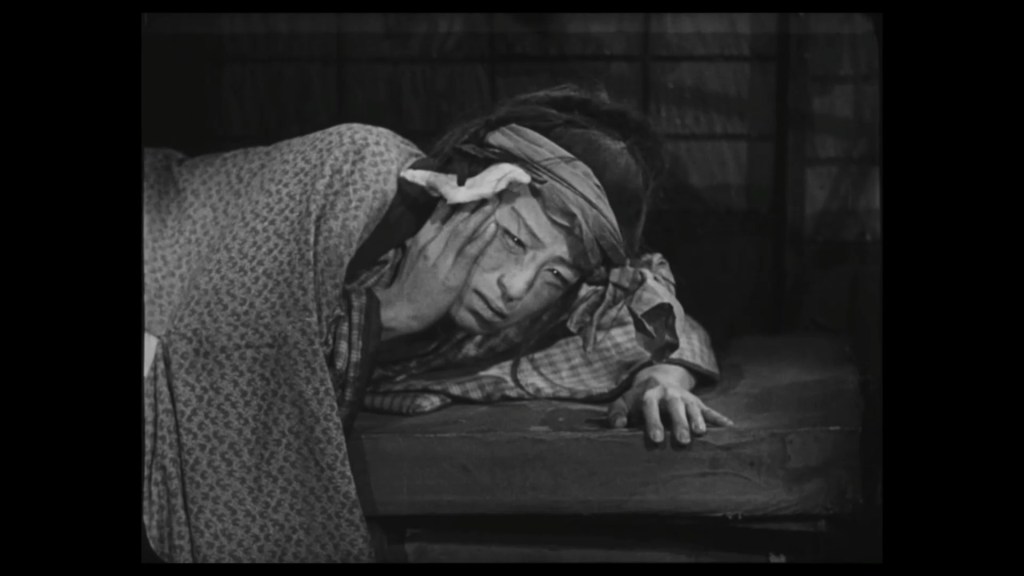

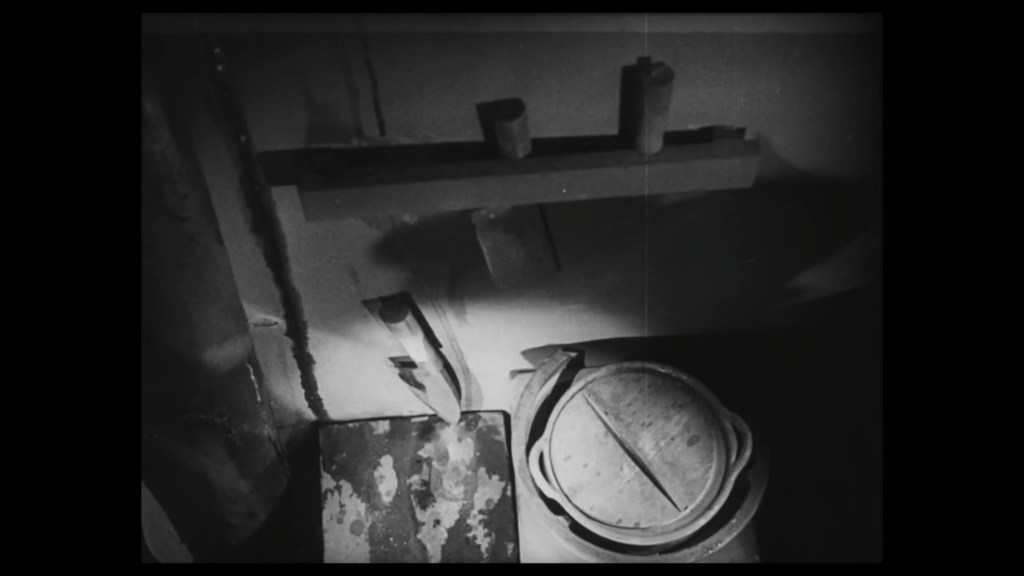

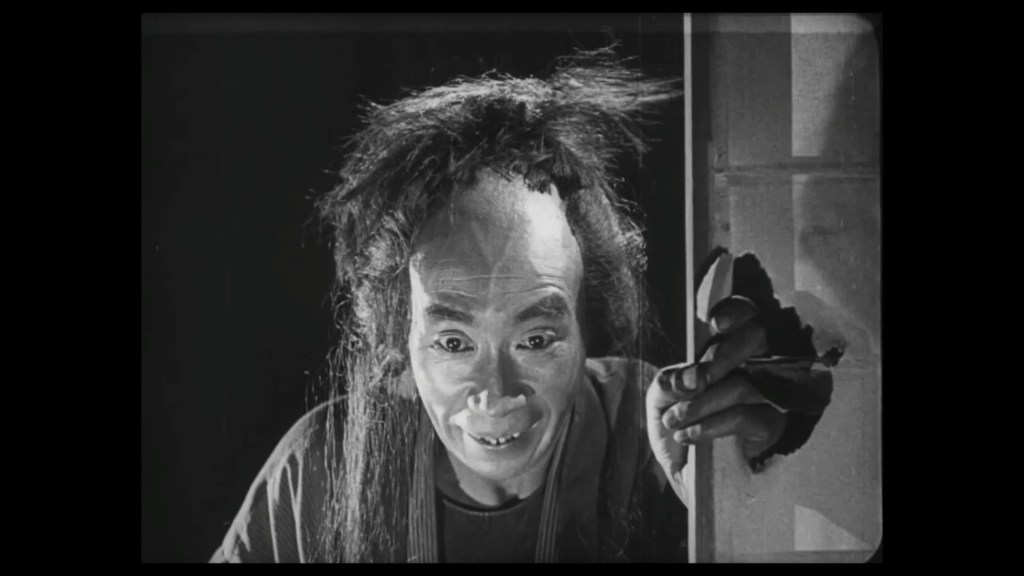

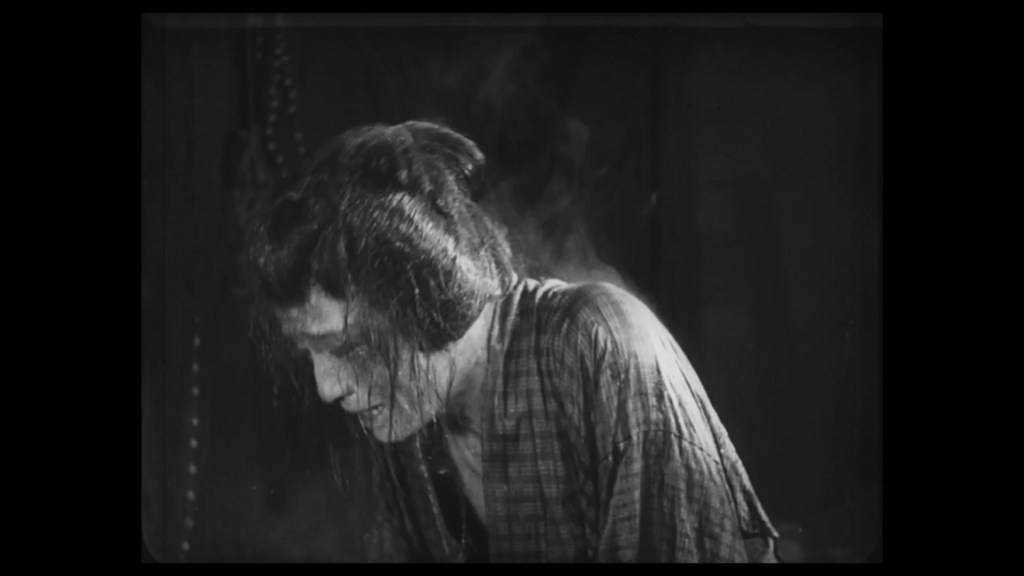

If the plot is mundane, the realization is superb. There are multiple flashbacks, which makes the narrative more complex – more subjective, more strange – than the above synopsis suggests. But it’s the world of the film that is so compelling. The whole story seems to take place at night, or else within a kind of contained nightmare. That might be a starless sky overhead, but it might as well be the void of any reality beyond the comfortless tenements and cacophony of the gambling dens and brothel. It is a forbidding, studio-bound world. It rains (and often you can see the characters’ breath) but there is no sense of the natural world beyond the dark streets, the grimy interiors. The characters who inhabit this place are, apart from the sister, forbidding and grotesque. From the frenzied brother, forever clutching his face, his throat, his blinded eyes, to the creepy, toothless neighbour, the sinister procuress, the bandaged rival and the cackling O-Ume – everyone is unwelcoming, exploitative, angry. The sets in which these characters live, or struggle to live, are marvellous. There are realistically threadbare walls, tattered paper doors, broken windows, forbidding staircases. The world of Yoshiwara is more complex, with multiple interior spaces joined by ornate panels, blinds, windows within windows. Kinugasa turns this space into a bewildering, overwhelming maze: swinging lanterns, spinning umbrellas, tumbling betting balls. And all filled with the mad bustle of drinking, gambling, laughing crowds. The combination of studio-bound sets, dim spaces, and claustrophobia feels very expressionist. (The theme of a wayward man abandoning a homebound woman – not to mention its moody rendering – made me think of Die Straße (1923), shown at Pordenone last year.)

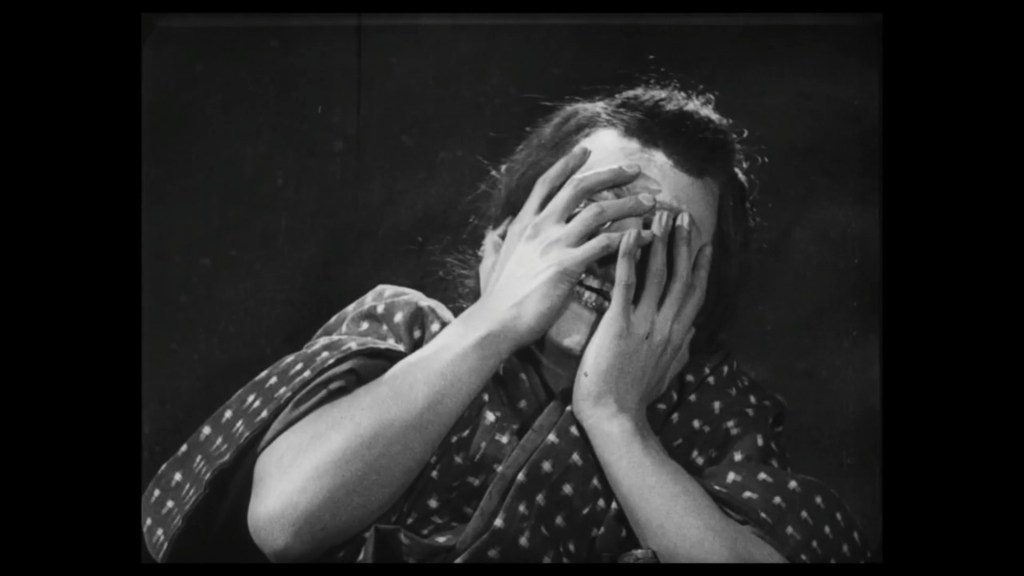

This transformation of physical space into psychological space is heightened by Kinugasa’s superb camerawork. There is a wonderful array of dramatic lighting, sudden close-ups, creeping tracking shots, sinister high-angle viewpoints. Just see how the first montage of the Yoshiwara gambling dens is rendered more effective by the prowling camera, the hallucinatory superimpositions, the leering close-ups. There is a fascinating balance between subjectivity and objectivity in the way the camera shares and/or observes the way characters experience the world. When the brother is blinded, for example, there is a dazzling flurry of pockmarks and lightning bolts that bubbles over the screen: we share the brother’s onrush of terror and bewilderment. But immediately afterwards, as the brother stumbles back and forth through the cackling crowd of gamblers, the camera pitilessly tracks back and forth, keeping its distance, watching him fall apart. The shock of subjectivity is followed by the chill of detachment.

The film’s blend of melodrama and expressionism comes to its climax in the final scenes. The brother recovers from his blindness, and we see the world as he sees it: darkness distorting, weird patches of light, solid objects rippling. But the reality he wakes to is like a living nightmare: the toothless, dishevelled neighbour assaulting his sister, the body falling before him. A series of dissolves transform the scene into a kind of vision, as though these images were also emerging from the brother’s former blindness. The siblings’ rush through the dark and rain is equally nightmarish, and the hut in which they shelter hardly comforting. Their bodies are soaked, and the marvellous detail of steam rising from their shoulders is both realistic and expressive. The titular crossroads of the film appears at the end like a slice of another nightmare. It’s two pale streaks of pathway, crisscrossing a despairingly black landscape. Dim, bare trees in the foreground, dim, distant houses in the distance. The brother crosses this otherworldly space to reach Yoshiwara, where he sees O-Ume and the rival he imagined he has killed. With a rapid montage of hallucinatory images, superimpositions, and distortions, he clutches his eyes and collapses – “This is the end!” he screams. And it is. There’s just one last scene: here is the sister, alone at the crossroads, hesitant, afraid. It’s a superbly disquieting ending to this bleak and gripping film. With touches of German expressionism ala Fritz Lang and French impressionism ala Abel Gance, Kinugasa’s Jûjiro still holds its own – it’s a concentrated, nightmarish, unsettling film.

I must finish by praising the musical accompaniment, which performed on piano and violin by Sabrina Zimmermann and Mark Pogolski. Their score was atmospheric, dramatic, and perfectly in keeping with the mood and tempo of the film. Bravo.

Paul Cuff

One thought on “Bonn from afar (2024, days 1 and 2)”