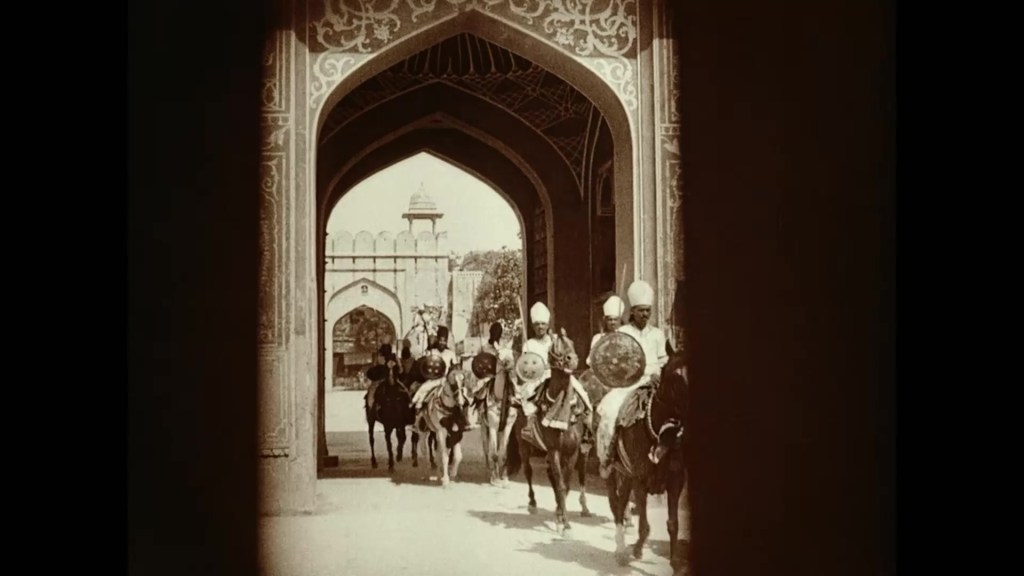

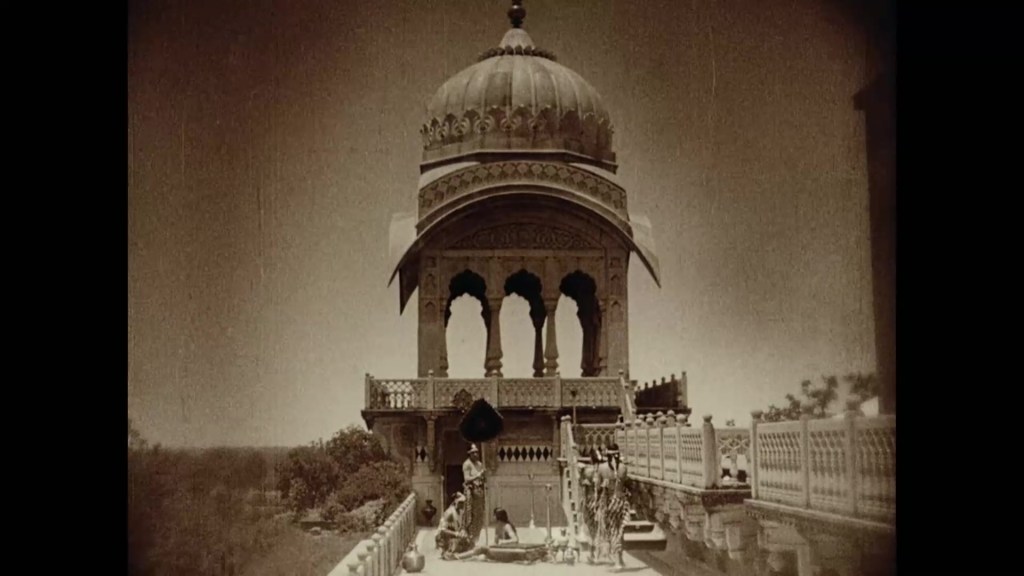

Another day (not) at the Bonn festival and another country to visit. Today we journey to India for the recreation of ancient religious drama. I outlined the context for Franz Osten’s German-Indian co-productions in my piece on Shiraz (1928). To recap briefly, these films were the brainchild of Himanshu Rai, who was instrumental in partnering Indian writers and performers with European filmmakers. Their first collaboration was Prem Sanyas, originally released as Die Leuchte Asiens in Germany in 1925 and The Light of Asia in the UK in 1926. Made with the support of the Maharajah of Jaipur (now in Pakistan), the film was shot entirely on location in India with (as the film’s opening titles remind us) no “studio sets, artificial lights, faked-up properties or make-ups”.

Prem Sanyas (1925; Ger./In./UK; Franz Osten/Himansu Rai)

The plot? Well, the film begins with a lengthy section of quasi-documentary footage around contemporary India. Some western tourists visit the Buddhist temple complex at Gaya. There, they encounter an old man who relates the tale of how Buddha achieved enlightenment below the Bodhi tree… The film then follows the story of Prince Gautama (Himanshu Rai), who is adopted by the heirless King Suddodhana (Sarada Ukil) and Queen Maya (Rani Bala). As the boy grows, he becomes increasingly conscious of the suffering of animals and the world around him. His father is warned by a sage that it is the boy’s destiny to renounce the throne, leaving him heirless. The king therefore tries to shelter the boy from all sight of suffering. When this doesn’t work, he finds him a consort. The prince falls for Gopa (Seeta Devi), who likewise is smitten with him. However, the prince is overwhelmed by the knowledge of suffering outside his pampered life and perfect marriage. Hearing the voice of God, he abandons his wife, his palace, and his family to live as an impoverished teacher. He converts crowds to his new conception of the world, and when Gopa encounters him again, she becomes his disciple. The flashback ends with the old man concluding this tale, then (very suddenly) the film ends.

Such is the narrative. And as a drama, it is a failure. The story is very thin, with characters barely sketched and with neither the interest nor the ability to suggest real, human psychology. (Hey, it’s a religious story, so I suppose expecting a real drama is a bit wishful.) As the story of one of humanity’s great teachers/enlighteners, it’s surprisingly inert. But because the characters are picture-book cut-outs, there is barely any ordinary human emotion to engage with either. It’s a very simply parable told very simply.

I say simply told, for there is no showiness to the film’s direction. This is a polite way of saying that the film isn’t very dynamic, let alone dramatic. There are few really telling close-ups (as if the film is afraid of exploring the reality of its human characters), and the editing between wider and closer shots is often rather clumsy. Few scenes use montage to create a sense of rhythm, and there is a kind of roughness to the way the film’s narrative is shaped. In part, of course, this is the fault of the original story: it’s a very simplistic tale and doesn’t offer a real “drama” as such. But I do wonder about the intentions of the filmmakers. Is the simplicity of the style – I am tempted to say the lack of style – a deliberate choice, or simply a limitation of means?

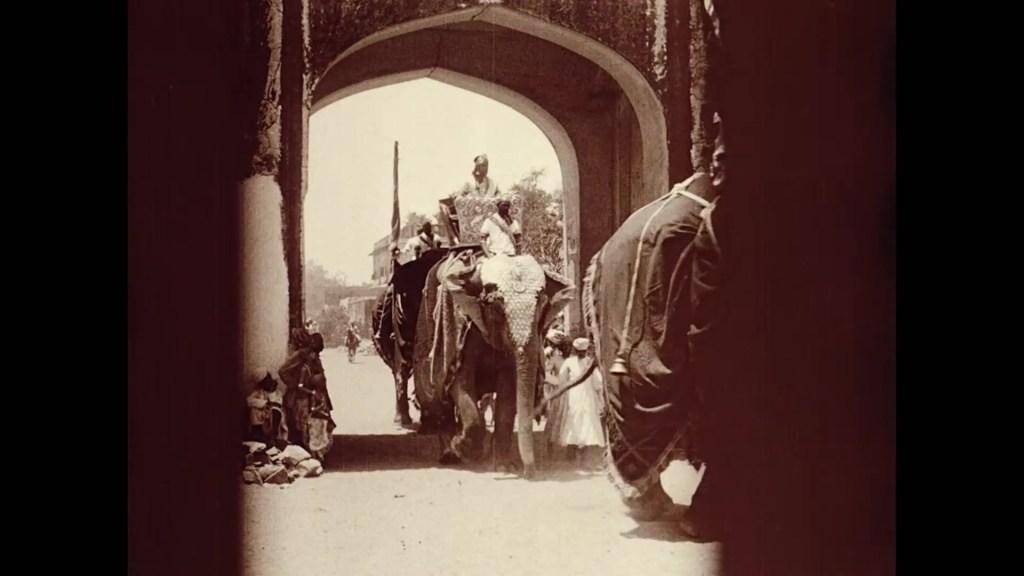

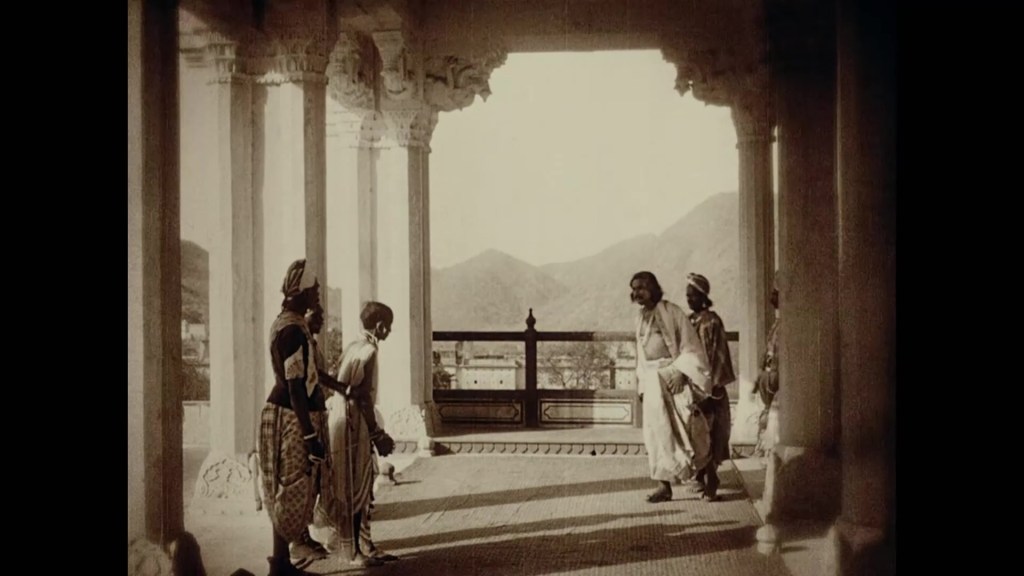

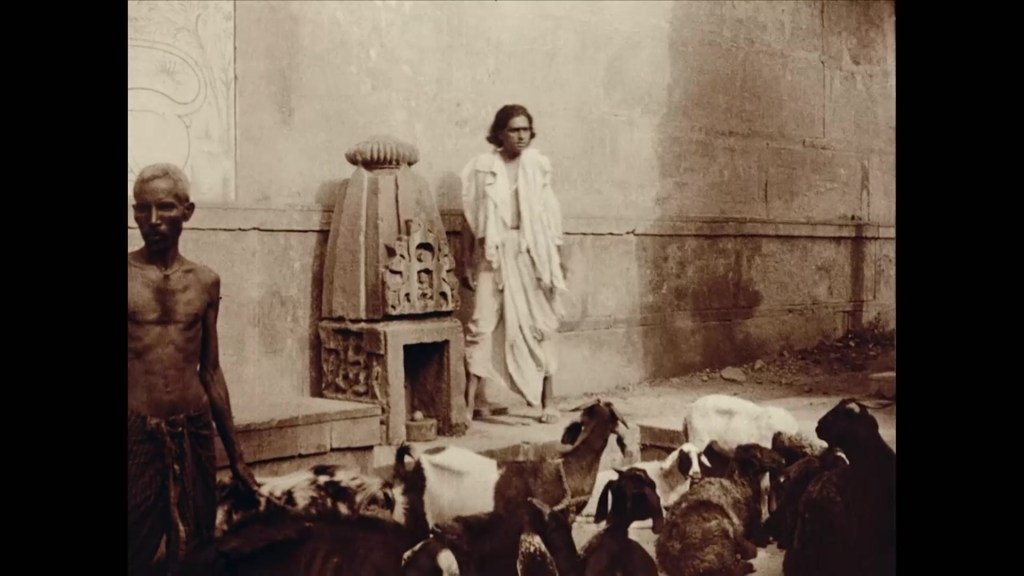

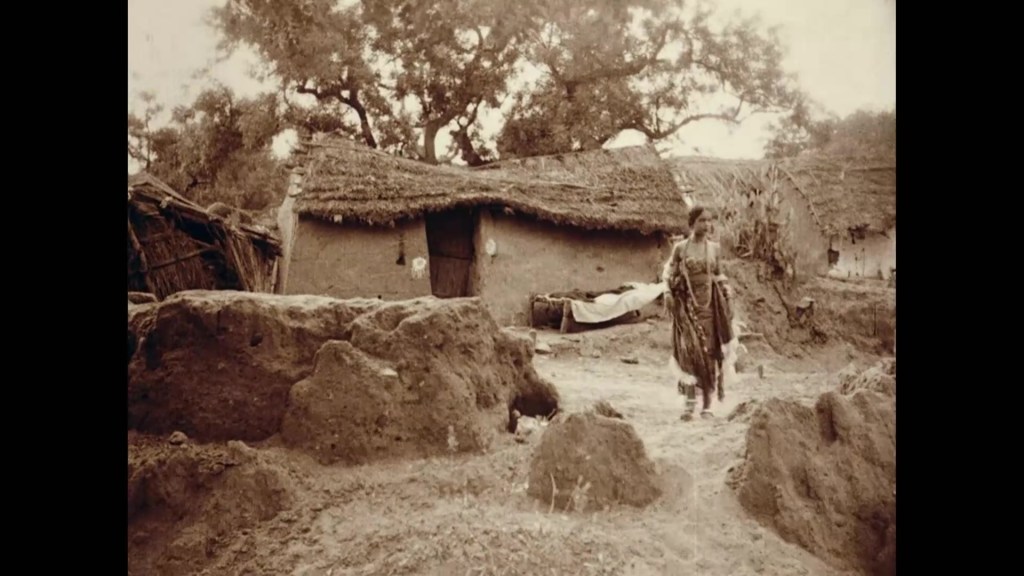

All this said, I didn’t care that the film wasn’t awash with stylistic flourishes or deft pieces of editing or camerawork. I didn’t care because this was one of the most beautiful films I’ve seen in a long time. Restored from a contemporary print released in the UK in 1926, Prem Sanyas is exquisitely tinted and toned and simply glows. For all that I have criticized (or at least, damned with faint praise) the lack of “style”, this film has no need to be showy when it uses real locations so well. So many views make you want to gasp, to spend time gazing at the frame. From ornate temples and elaborate palaces to dusty streets and overgrown gardens, this film is as astonishing document of time and place. I could rave for hours over the photography, the way the tinting seems to make you feel the heat and the haze and the dust and scent of the locations. I’ve taken a large number of image captures, but I could have taken any number more. The drama might have been inert, even inept, but I was captivated by the film itself – by the sheer aesthetic gorgeousness of the image.

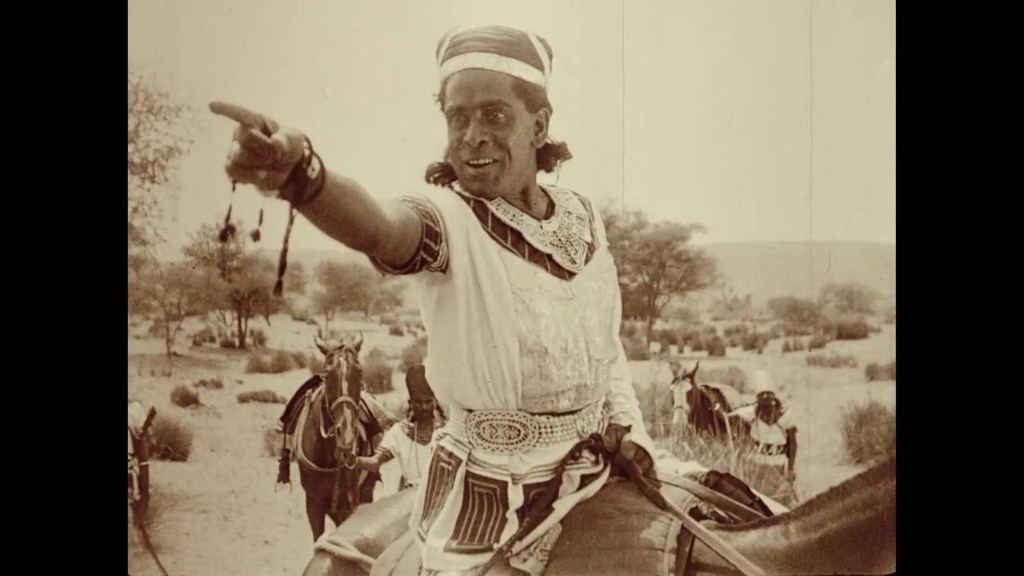

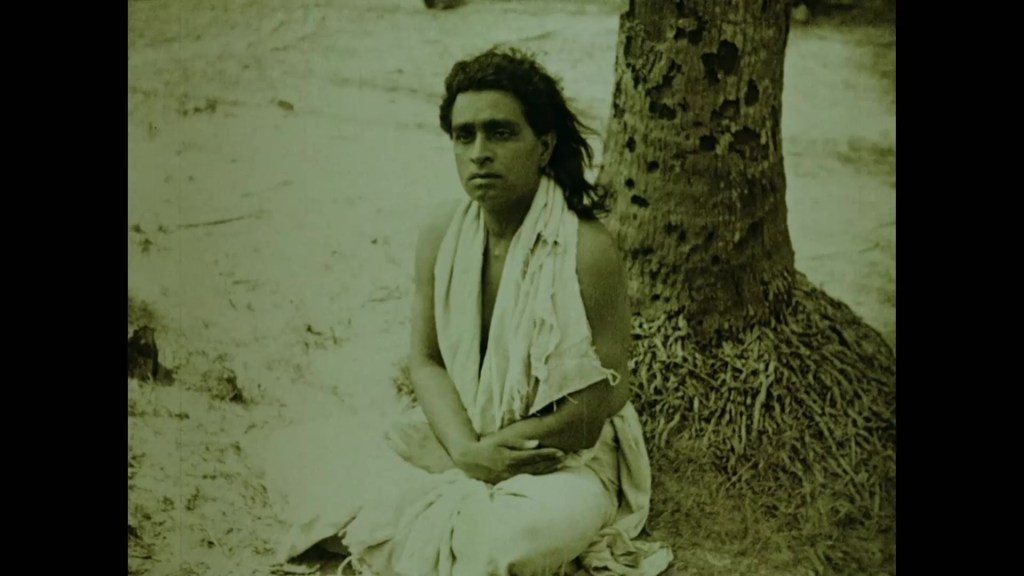

To return to something of the dramatic substance of the film, I must discuss the performers. I must begin by repeating what I said in my piece on Shiraz: I simply don’t think Himanshu Rai is an engaging screen presence. I found him stiff and awkward in Shiraz and I find him stiff and awkward in The Light of Asia. Given that he’s meant to be playing a religious prophet and visionary, I find him utterly unconvincing. He is both oddly stylized (holding poses, holding glances) and oddly restrained (not doing anything!). I would welcome a down-to-earth prophet, a recognizably human figure who connects to the sufferings of man. But Rai is neither a magnetic divinity nor a vulnerable human. He’s an oddly inert prophet and an oddly inarticulate teacher.

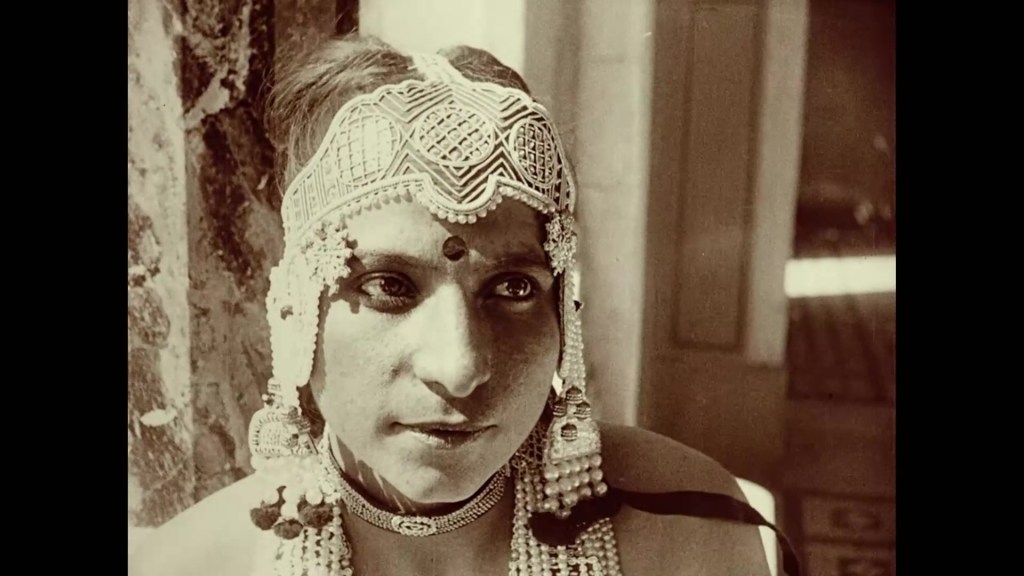

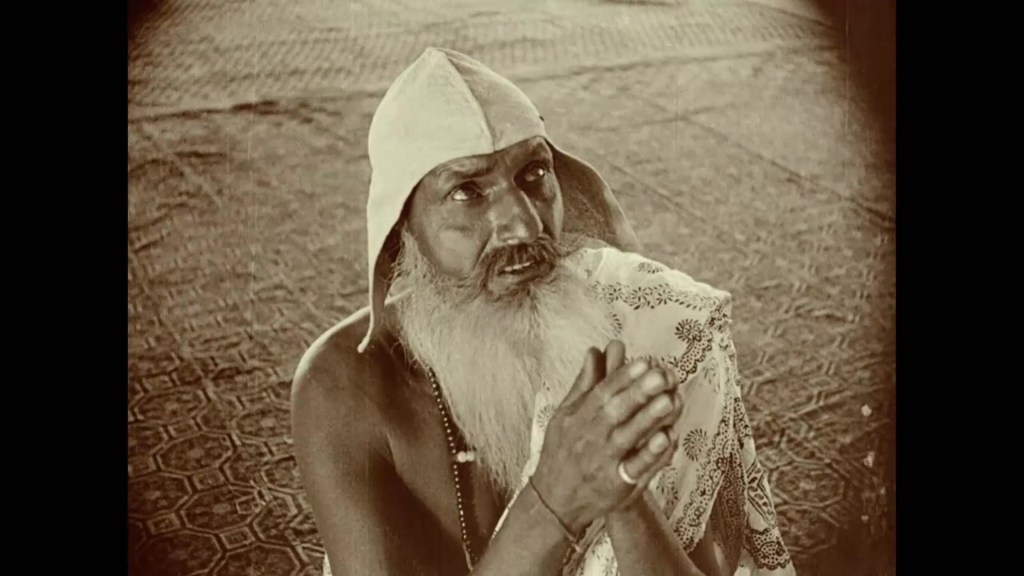

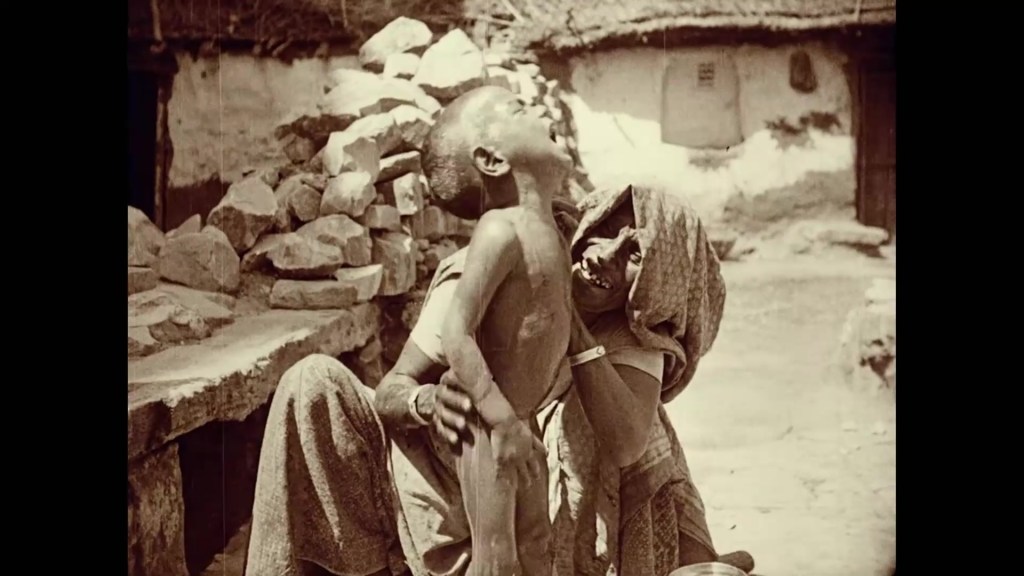

Rai’s limitations are shown up by the fact that everyone around him – and I mean everyone – has such great presence on screen: from the non-professional actors who play the minor characters to the real beggars and street performers who populate the world at large. Their faces and bodies are immensely interesting to behold. Here are real faces, real lives, real sufferings embodied for us to see. If I can’t see what the fuss is over the Buddha himself (or at least, Rai’s Buddha), I can absolutely see the fuss over the suffering of the world. The real locations and real extras are remarkably tangible, remarkably vivid.

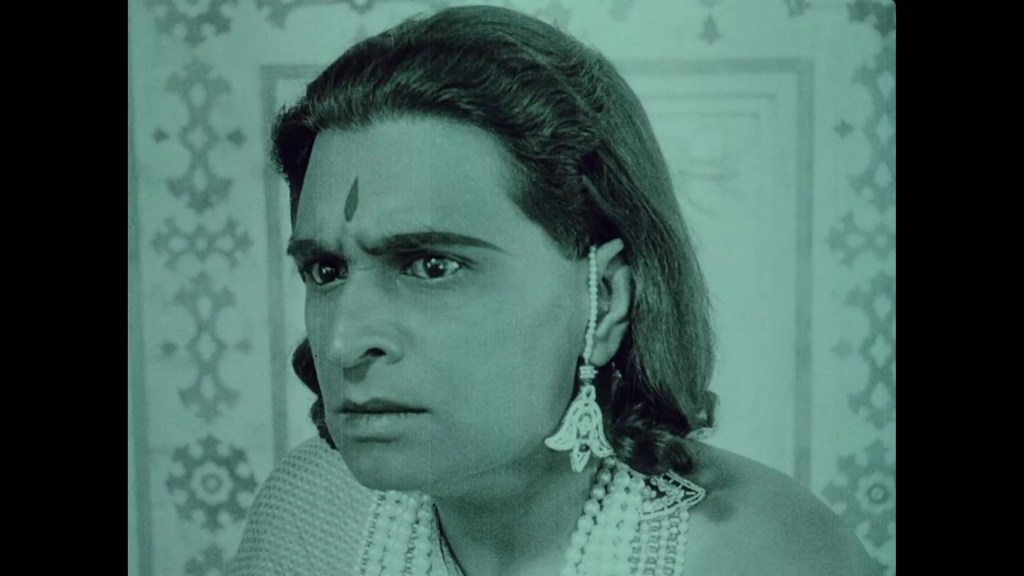

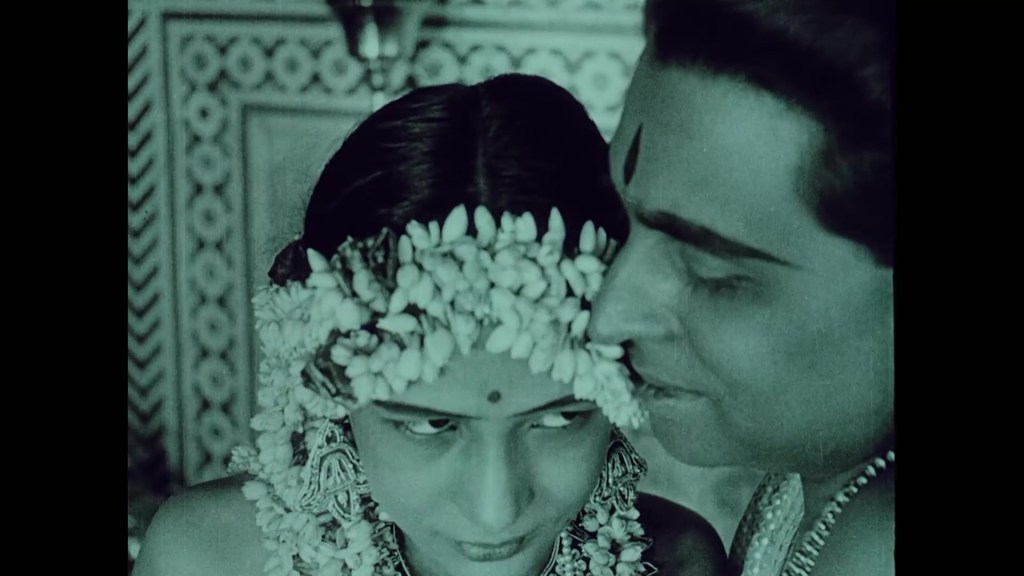

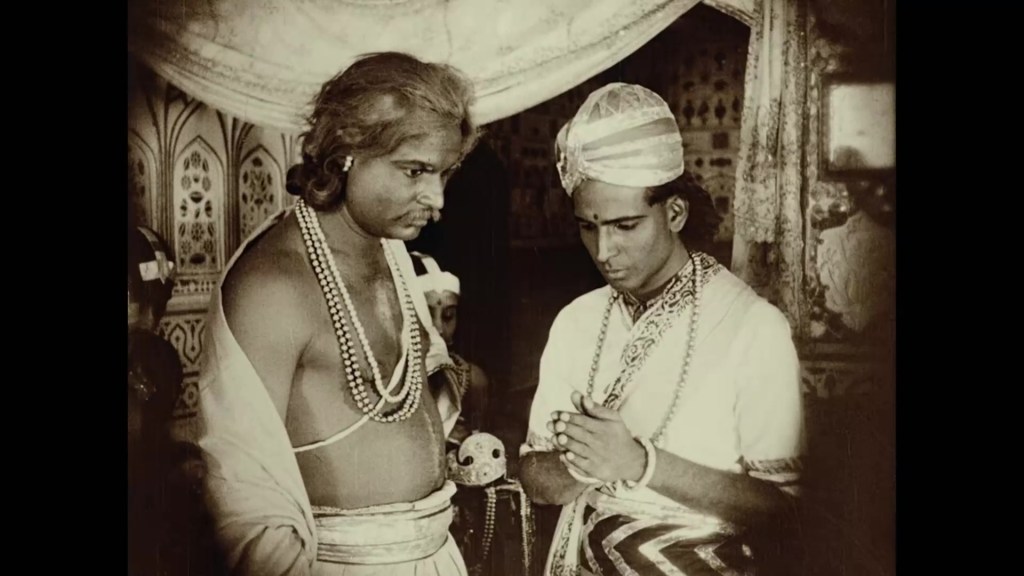

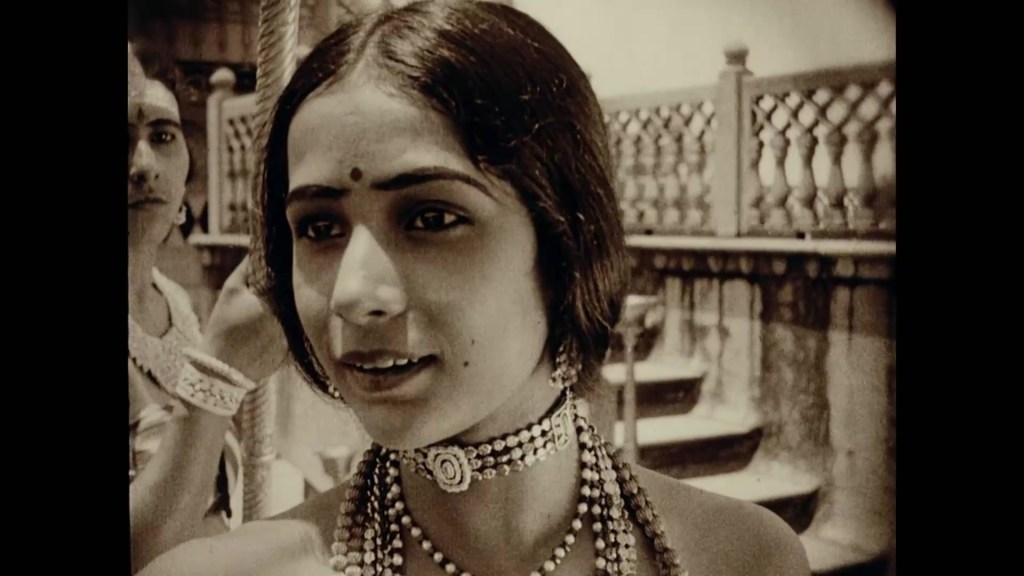

As the king and queen, Sarada Ukil and Rani Bala are pleasingly unpretentious. Free from any posturing, gesturing, or theatrics, they are as real as figures from a mystery play – ordinary and extraordinary at the same time. Then there’s Seeta Devi, who was by far the most striking presence in Shiraz. Here, she looks scarcely more than a child – indeed, she was thirteen at the time of filming. A real child to play the prince’s child bride. In my piece on Shiraz, I remarked that she was the only performer to offer a really defined performance, i.e. someone who was palpably playing for the camera, for us. Her role, as a manipulative figure wishing to shape the drama, perfectly suited her performance style. In Prem Sanyas, she is free of mannerisms, of technique. True, she is not given much of a character to embody, but nevertheless there is a naturalness to her embodiment of Gopa that is moving in itself. And though she has yet to grow into her adult body, or adult confidence as a performer, she is still radiant on screen.

The soundtrack for this performance was compiled by Willy Schwarz and Riccardo Castagnola. It consists of (what I take to be) prerecorded sections of music, historical recordings, and ambient acoustic sound. Most of these sample the sounds of India, through instrumental choices or the sound of crowds/prayers/chanting etc. I found it a little distracting to hear recorded effects during silent scores, even in the vaguest form like the sounds of praying and general bustle offered here. While it certainly fits the setting of the film, it doesn’t suit the period of the film’s making – i.e. its silent aesthetic. The film is so overwhelmingly visual, I didn’t want a composer trying to “complete” the pictures with real sounds. I much preferred the sections of instrumental music, which felt much more in keeping with the period and setting – and the film’s historical and aesthetic origins. That said, I’ve heard infinitely worse “acoustic” soundtracks, so I’m not complaining too much.

Overall, Prem Sanyas was an excellent experience. I wrote recently about another religious parable, The King of Kings, and when watching Prem Sanyas I was reminded of the many reasons I disliked DeMille’s epic. Despite all the awkwardness of Prem Sanyas, the absolute reality of its mise-en-scène, of the places and the people who inhabit it, make it a far more rewarding viewing experience than time spent in DeMille’s artificial holy land.

Paul Cuff