Day 10 already! (To be fair, it was about ten days ago now.) Our final film from Bonn comes from France, and it’s one that I confess to have had on my shelf for three years, unwrapped and unwatched. I suppose one of the functions of a festival is chivvy you to see things you’ve never quite got round to watching at home. (Even if, thanks to the miracle of streaming, I am still watching it at home…)

La femme et le pantin (1929; Fr.; Jacques de Baroncelli)

The film is one of several famous, and not-so-famous, adaptations of Pierre Louÿs’ eponymous novel (1898). The plot is inspired by a Goya painting (“El pelele”, 1791-92) of four women capriciously throwing a man-size doll into the air. In the film’s opening scene, we see this painting come to life. After this little prelude, we are introduced to Don Mateo (Raymond Destac), a Don Juan-ish figure “known throughout Spain”, who is travelling by train when he meets Conchita (Conchita Montenegro). She catches his eye when she fights with another woman and Mateo helps separate them. Months later, the pair meet again at a party thrown by Don Mateo at his “palace” in Seville. Conchita flirts with him and invites him to find her at home with her mother. Mateo does so, tries it on, is rejected – and then invited back another time. He falls in love but is jealous. He wins favour with Conchita’s mother by giving her money, saying he will marry Conchita. However, Conchita sees the money changing hands and tells him never to come again. Mateo tries to distract himself from the memory of Conchita, but their paths cross again in Conchita’s new home in Seville. She tells Mateo that she loves him, and he swears by the Madonna that he will never leave her. But no sooner are these words spoken than a rival suitor turns up, the very man who made Mateo jealous before. Another rift, another reconciliation. Conchita arrives chez Mateo and he shows her around (she wants to see the bedroom first). But then she leaves him a note saying that he doesn’t love her so she’s leaving. Mateo goes travelling, arriving in Cadiz – which is where Conchita happens to be, along with her rival suitor. Mateo watches her dance, then Conchita approaches and flirts. He threatens to kill her, and she laughs him off, telling him that she no longer loves him. But a note of tenderness suggests that she may still have feelings. It’s enough for Mateo to hope once more. But soon he realizes that she is performing a naked dance for select clients upstairs. He watches, furious and entranced, from the window – but then he bursts in, chases out the clients, and threatens Conchita. Once again, she accuses him of not really loving her. She demands that he make her rich, to be “worthy” of him. So they get engaged and he smothers her with finery. He buys her a palace and she wishes to be the first to enter to receive him. But when he arrives at midnight, she shows off her finery through the bars of the gate – and then, laughing, tells Mateo to leave. “You’re not worthy to kiss my foot!” Mateo claws at the gate, his hands bleeding, until he sees Conchita embrace another, younger, man. She tells him that this man is worthless, but she adores him. Mateo retreats to a dance hall. The old rival turns up and boasts of the money Conchita gave him. But it turns out that the “rival” is already engaged, and he was being used by Conchita to make Mateo jealous. “All Seville is laughing at you!” Conchita turns up again, flirting, laughing, contemptuous. Mateo knocks her down, but she draws a knife. He hits her repeatedly. She laughs, says she’s sorry, says she’s his. A year later, at the Seville cabaret. Mateo reports that his happiness lasted two weeks, that Conchita was “a devil” and he left her six months ago. But there she is again, dancing. He sends her a note, saying he forgives her and will kiss her feet. She gives the note to her new suitor. Mateo’s gesture of fury dissolves into that of Goya’s doll. The doll is thrown, then plummets to earth in a heap. FIN.

At the end of my teens, Pierre Louÿs seemed very exotic and risqué. I encountered him first through Claude Debussy’s various adaptations of his 1894 collection Les Chansons de Bilitis (composed 1897-1914). To someone who had led a sheltered life in the countryside, Louÿs’ louche, sensual work was at first appealing – and faintly sinister. The 1920s edition of his complete works that I bought was replete with lurid art deco illustrations and an aura of faded decadence. Faced with this veritable brick of a book, I soon realized that the contents were not my cup of tea. I trudged through a chunk of it, but eventually gave up. It sat on respective generations of shelving before I sold it, as though to cleanse myself of Louÿs. Since then, though never consciously, I’ve avoided all other incarnations of his work: from songs (Charles Koechlin) and opera (Arthur Honegger) to cinema. Though there have been several adaptations of La femme et le pantin, Josef von Sternberg’s The Devil is a Woman (1935) and Luis Buñuel’s Cet obscur objet du désir (1977) are famous independent of their literary source. I confess that I’ve never been particularly drawn to either (in terms of stardom) Marlene Dietrich or (in terms of mid-twentieth century European auteurs) Buñuel, which I’m sure condemns me for all eternity in the eyes of many. (I think the sheer fact of their centrality to the cinematic canon lessened my interest. As someone who always wants to write about what they love, I always feel put off by stars or directors who have already accumulated generations of literature. I never feel at home in a crowd.) Nevertheless, I preface my comments on Baroncelli’s film by this admission because it means that I come to La femme et le pantin with eyes undazzled by later adaptations. It was even with a faintly guilty sense of familiarity that I recognized in this film both the old attractions and the old frustrations of its source material. I realize how odd it sounds for someone my age (still, just, under 40) to feel more familiar with Pierre Louÿs than with Luis Buñuel, but such is my bizarre cultural pedigree.

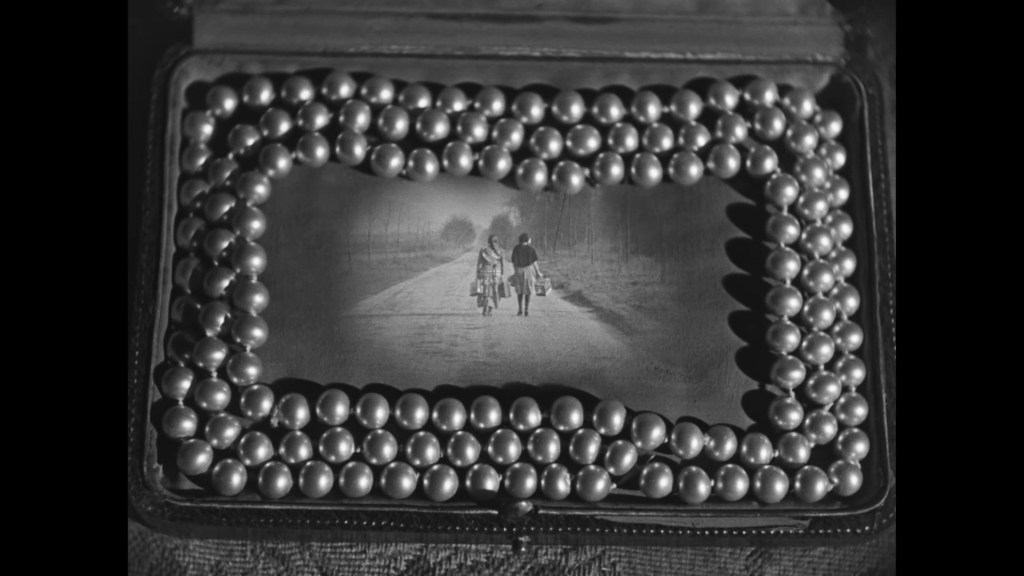

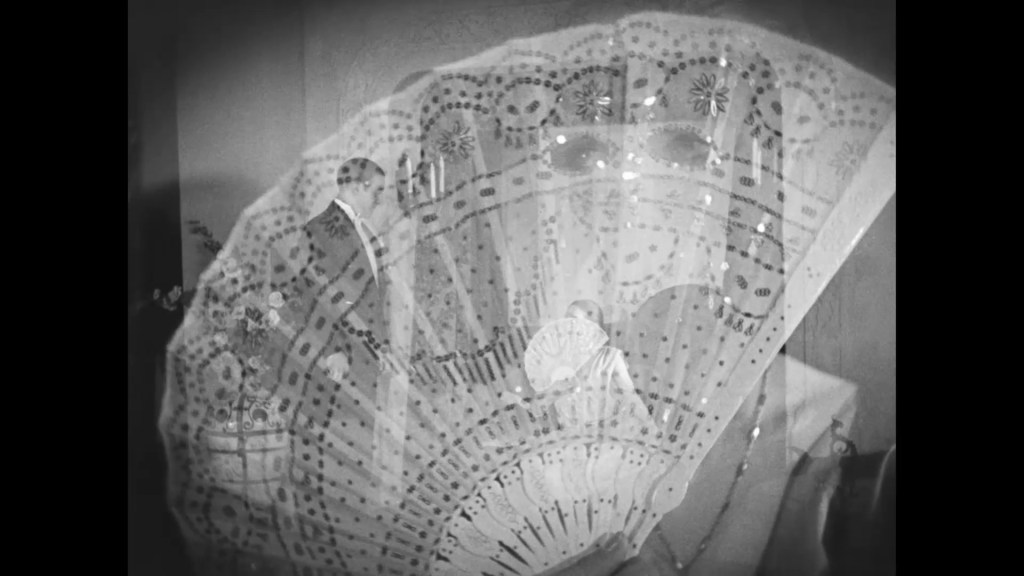

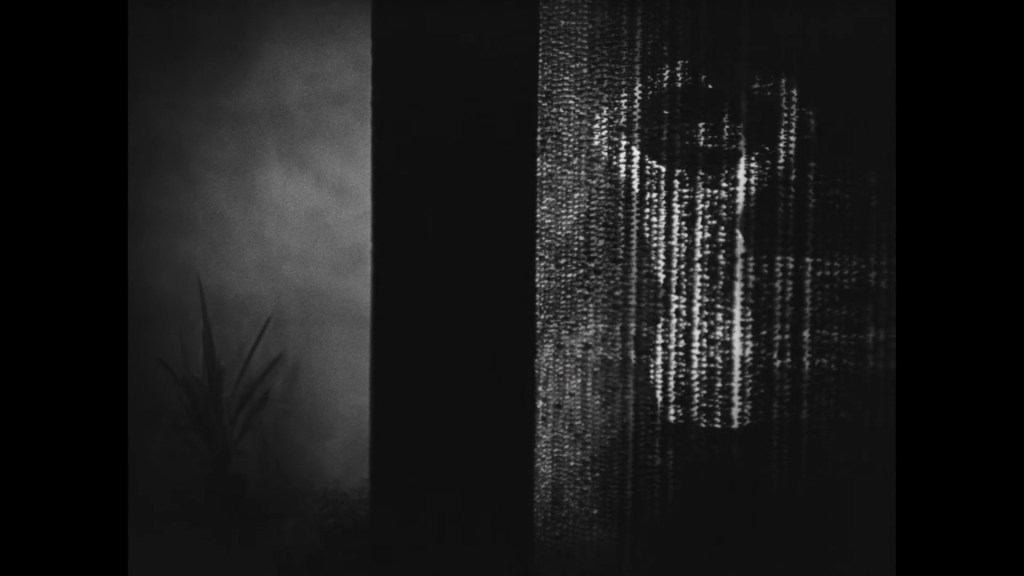

So, the film. Firstly, it looks sumptuous. The opening exteriors of the train crossing the snowy mountains are stunning, and there are some gorgeous glimpses of Seville and the Spanish coast. But the rest of the film is overwhelmingly set within complex interior spaces. Baroncelli goes to great lengths to provide windows, doors, grilles, bars, ironwork, glasswork to frame (and frustrate) Mateo in his encounters with Conchita. His two “palaces” offer fantastical décor, replete with fountains outside (a crucial motif, as Conchita literally and figuratively washes her hands) and luxurious dens within. It all looks like some fabulous art deco fantasy, with endless open halls, vanishing corridors, skin-lined floors, tapestry-lined walls, Moorish columns and arches… The first party we see at his palace features the women wearing Velasquez-inspired dresses, which are extraordinarily eye-catching. Yes, indeed, this is an exquisitely mounted film. The photography, too, is absolutely superb. The lighting is impeccable, the shadows and framing and compositions are incredible – just going through the film again to take some captures, I find myself purring over all the beautiful images.

The two stars of La femme et le pantin were unfamiliar to me, and glancing at their filmographies neither seems to have featured in too many well-known productions – or had especially extended screen careers. Appearing as her namesake, I found Conchita Montenegro very appealing. She’s as charming, lithe, and sensuous as one could wish for – and quick to smile or laugh or change her mood and slip away from one’s grasp. If there are very few moments of empathy or emotion in her performance, it’s because that’s what her character dictates. I did not, ultimately, warm to her because I’m not meant to – she is (per Buñuel’s later title) that obscure object of desire. As for Raymond Destac, I likewise admired him in a somewhat distant way. Like Conchita, Don Mateo is an opaque character. We’re not meant to like him, he’s a kind of cipher for the masculine desire to conquer and possess. He’s perfectly good, but he has absolutely no depth. The trouble is, he’s not even interesting as an opacity or a surface. He fulfils his dramatic function admirably. Am I damning with faint praise? I don’t mean to, but this is precisely the kind of film that has never appealed to me. (See my previous efforts to like the films of Marcel L’Herbier.) La femme et le pantin is a lucid dream, or nightmare, in which nothing can be attained or achieved. I recall again those pages of Pierre Louÿs. Shady narrators telling stories of ungraspable women in luxurious, sinister nocturnal haunts. Well-appointed interiors and frustrated desires… Like I said, not my cup of tea.

Oh dear, oh dear, is this all I have to say? Am I simply failing as a critic? As an exercise in controlled style, I gladly acknowledge that La femme et le pantin is an exceedingly good film. Everything about it works. I could see and understand what it was doing and why, but at nearly two hours it’s quite a sustained exercise in disappointment. There are only so many variations on the theme of “man stands in ornate mise-en-scène while being unable to access woman” that I found interesting. The narrative is deliberately repetitive and inconclusive. I suppose the point of it all – and the novelty – is that the spectator is as curiously unsatisfied as the male protagonist within the film. The story is essentially that of Carmen, but without the literal and symbolic penetration of the woman at the end – the final, fatal stabbing that ends the original story, together with Bizet’s opera and the multiple film versions. (I write about Ernst Lubitsch’s adaptation of 1918 here.) Louÿs’ version of this story removes all the dirt and sweat, distinguishing itself by an aura of exquisite refinement and controlled perversity. So too with Baroncelli’s film. It’s cool, detached, stylishly aloof. No doubt it is simply my own taste that sits at odds with the film. Just as I wearied of page after page of exquisitely elusive suggestiveness with Louÿs, so did I ultimately with Baroncelli’s highly competent adaptation.

Finally, a word on the restoration of La femme et le pantin, which was undertaken by the Fondation Jerome Seydoux-Pathé in 2020 – and released on DVD/Blu-ray in 2021. The music for the Bonn presentation of La femme et le pantin was the original score by Edmond Lavagne, Georges van Parys, and Philippe Parès, arranged and orchestrated (for a small ensemble) by Günter A. Buchwald. (Thankfully, this same score is also presented on the DVD/Blu-ray.) It was a lovely, elegant, Spanish-inflected score, which follows the rhythm of the film fluently and convincingly. In a curious way, its charm and easy functionality suited the cool tone of the film. I wonder what the original composers made of the film’s tone, and to what extent they consulted Baroncelli. I could easily imagine something sharper and crueller being composed, especially for a full orchestra, which would have been a more fully engaged (more interpretive, interventionist) accompaniment.

Since seeing this restoration, I have also tracked down a previous restoration by Pathé Télévision from 1997, which was broadcast on ARTE and released on DVD in France as an extra on an old edition of Cet obscur objet du désir. This has a score by Marco Dalpane for similar forces to those used by Lavagne/Parys/Parès, and with a very similar language and tone. Title font aside, the 1997 and 2020 restorations are virtually identical – save for one significant difference. The montage of Conchita’s naked dance sequence is slightly more elaborate in the 1997 restoration, and – most crucially – climaxes with a shot that appears only briefly in the 2020 restoration. In the 1997 restoration, Conchita appears superimposed within a champagne bottle, turning around and showing her entire body (i.e. front-on) to the viewer. Having the unreachable form of her naked body appear in the bottle seems to me a much more satisfactory climax (though both “satisfactory” and “climax” are, of course, the opposite of what the vision represents for the on-screen spectators) than in the 2020 restoration. How odd that the shot should be cut, and the montage of the sequence subtly different. The 2020 restoration credits cite “an original nitrate negative” in the Fondation Jerome Seydoux-Pathé collection, but the status of this print in relation to the film’s release history is (to me, anyway) unclear.

Despite this question of completeness (or censorship), this is indeed a beautiful restoration with excellent music. My own reservations about the film should not prevent anyone tracking down the film on home media. This sumptuous, cold, and cruel film isn’t my cup of tea,* but it might be yours.

Paul Cuff

* I see that I have used this phrase three times, which is a failure of linguistic imagination. It’s also misleading, since I don’t even drink tea.

One thought on “Bonn from afar (2024, day 10)”