Between 29 August and 25 September 2024, the Cinémathèque française is hosting a retrospective of the works of Abel Gance. This programme presents (almost) all the surviving films and television work Gance made across his lengthy career. The retrospective features new restorations, as well as presentations by restorers and scholars. Time and geography permitting, I would have attended every screening. (This is not the first time in my life that I have longed to be Parisian.) However, across the weekend of 13-15 September I was able to make a targeted smash-and-grab raid on Gance’s early silent filmography. Across three days, I attended seven screenings and saw five feature films, two shorts, and a curated presentation of fragments. I will devote a post to each day of cinemagoing that I attended in the retrospective, and another to offer some concluding thoughts on the experience as a whole. (There might even be an anecdote or two.) So, without further delay, day one of my trip…

Friday 13 September 2024: Salle Georges Franju, 6.30pm

The first film I saw was Les Gaz mortels (1916), the earliest surviving multi-reel production in Gance’s filmography. In the spring of 1916, producer Louis Nalpas ordered Gance to head south with a small cast and crew and return to Paris a.s.a.p. with two films. According to Gance, he wrote the scripts on the train to Cassis and shot Les Gaz mortels and Barberousse simultaneously. (“Quite a business!” Gance recalled to Kevin Brownlow. “But it gave me a great facility. I really had to exert myself – it was like doing one’s Latin and Greek at the same time.”) The first film to be edited was Les Gaz mortels, released in Paris cinemas in September 1916. The name of Gance’s employers, Le Film d’Art, is a little misleading: much of the company’s output at this time was made for a commercial market. In wartime France, escapism jostled strangely alongside grim realities. For its initial release at the Pathé-Palace, Les Gaz mortels took its place in a programme that included episodes from the Pearl White serial The Exploits of Elaine (1914), the latest Rigadin comedy starring Charles Prince, and newsreels fresh from the frontline (La Presse, 1 September 1916). Given this context, the plot that Gance concocted for Les Gaz mortels while his train rattled the length of France is a pleasing mix of popular genres: it is at once a Western, war drama, suspense drama, melodrama, and race-to-the-rescue film…

The renowned French scientist Hopson (Henri Maillard) and his American assistant Mathus (Léon Mathot) work in Texas, where they are called to help Maud (Maud Richard) escape the clutches of Ted (Doriani), a drunkard who supplies the two researchers with snakes from Mexico. Maud is rescued and returns with the scientists to France, where a romance develops between her and Mathus. But war is declared, and Hopson’s son is killed by poison gas on the frontline, leaving Hopson’s grandson André (Jean Fleury) in the care of Edgar Ravely (Émile Keppens) and his wife Olga (Germaine Pelisse) – who hope to profit from their role. But Hopson takes André from his carers, who then join forces with Ted to seek revenge. Edgar and Ted sabotage the poison gas factory run by Hopson and Mathus, while Olga unleashes a poisonous snake into André’s bedroom…

Les Gaz mortels is familiar to me, as I have watched the DVD several times. (The film is also currently available via HENRI, the free online film selection from the Cinémathèque française.) However, it was an entirely unfamiliar experience on the big screen – and projected on 35mm. Unlike the entirely silent DVD issued by Gaumont, this Cinémathèque screening was accompanied by a pianist from the improvisation class of Jean-François Zygel. (One minor bugbear with the retrospective is that not all the performers are credited in the programme or online. I have tried to find the names of all the musicians but lack details for two of them – the first being the fellow who accompanied Les Gaz mortels.)

Les Gaz mortels is a compact, well-made, and rather fun drama. At just over an hour, it was Gance’s longest film to date, and it races along to a satisfying conclusion. It is also beautifully shot by Léonce-Henri Burel. I adore the opening scenes set around the Mexican-Texan border but filmed on the south coast of France around Cassis. It was clearly a location Gance loved. Many of his early films were shot amid these sun-soaked landscapes, and Burel’s photography makes the most of the landscapes, the seascapes, the gorgeous southern light.

Seeing the film projected on the big screen of the Salle Georges Franju was a particular pleasure. I spotted details I’d never noticed before, like the initials carved onto the branch of a tree overlooking the sea, where Maud pauses for a moment on her search for vipers. Indeed, Maud’s snake-hunt features some of the most beautiful, naturally back-lit scenes of the film. Her hair is transformed into a chaotic halo, like a white flame flurrying worriedly about her head as she runs in terror from the snake-infested scrubland. Then there is the scene of her wakeful night, spent longing for release from capture. The lighting is simply exquisite, giving this entirely incidental scene a curious poignancy. The character is contemplating her imagined future, and we contemplate the image of her at the open window – seduced for a few seconds by the same evening light, the same moment of calm.

But such moments of “calm” are rare in a film that deals primarily in seething skullduggery and dramatic spectacle. The film climaxes with complex intercutting between various spaces. The parallel race-to-the-rescue scenes cut not just between two different locations, but between multiple spaces within each location. The interiors where the snake is let loose boast some very striking close-ups (the snake sliding over the neck of a doll) and effective low-key lightning (Olga peering into the snake tank), just as the exteriors offer some travelling shots and intriguing views of the (unnamed) town and landscape being swathed in swirling banks of gas.

The performances are rather mixed in style. As the drunkard Ted, Doriani is as crudely villainous as anything from a serial quickie. The two bourgeois baddies, Émile Keppens and Germaine Pelisse, are more convincing (if two-dimensional). Maud Richard is charming enough, but her toothy grinning can be slightly gawkish. Henri Maillard is a little stiff as Hopson, while Léon Mathot is alternately winsome and bathetic as Mathus. Of course, Les Gaz mortels offers scant dramatic depth for the performers to plumb, but even so… I have mixed feelings about Mathot as an actor. He is a reliable, sometimes strong presence on screen, but when tasked with expressing sadness he has a certain default expression that strikes me as mawkish. It’s interesting that such an important early male star should be so vulnerable, so evidently sensitive, on screen, but I am not affected – not moved – by his performances. He signals sentiment while (for me) never quite giving the illusion of real depth. (Several years after his collaborations with Gance, Mathot is still the same mawkish presence in Jean Epstein’s L’Auberge rouge (1923) and Cœur fidèle (1923), films that are beautiful to look at and, alas, highly soporific.)

The 2006 restoration of Les Gaz mortels is based on a (jumbled) negative print that survived without titles. Thankfully, it was possible to reconstruct the film’s titles and original montage – though the print remains untinted, which may not be how audiences saw it in 1916. As a study by Aurore Lüscher explores, Gance (in his notebooks from 1916) refers to the film variously as “Le Brouillard Rouge”, “Le Brouillard de Mort”, and “Le Brouillard sur la ville”. The title “Red Fog” makes me wonder if Gance had a colour-scheme in mind to heighten the climactic images of fire and gas stand out visually. (There are also nighttime scenes that could be clarified by some blue.) This reservation aside, the film looks as good as it can, and it was a great pleasure to see projected.

Friday 13 September 2024: Salle Georges Franju, 8.15pm

As soon as the first screening ended, so the queue began for the next. After a few minutes’ respite to chew some bread and gulp down water, we were let back into the Salle Georges Franju for La Dixième symphonie (1918). I have seen this film several times before, but the new restoration shown at the retrospective was nothing short of a revelation. The print that served as the basis of the restoration was exquisitely tinted and toned, a beautiful example of how elaborate and enriching contemporary prints could (and can) look. In his introduction to the film, Hervé Pichard explained that the restoration retained the original title cards between “parts” giving notice to spectators of a short break while the reels were changed. As Pichard put it, retaining these titles were a mark of respect for the original celluloid (and its exhibition context). A nice touch, given that we were watching the film via a DCP.

La Dixième symphonie is both a vivid melodrama and an ambitious foray into new expressive possibilities. Eve Dinant (Emmy Lynn) marries the widowed composer Enric Damor (Séverin-Mars) and adopts his daughter, Claire (Elizabeth Nizan). The latter is pursued by the exploitative Fred Ryce (Jean Toulout), who is also blackmailing Eve over her involvement with the death of his sister. Eve’s attempts to prevent Claire’s marriage are misinterpreted by Enric, who thinks she is having an affair. He finds solace in music, composing a symphony that expresses his sorrow and its transformation. The drama is resolved when the apparent rivals in love, Eve and Claire, confront Ryce and reveal the truth to Enric.

If this plot is like something out of D’Annunzio (whom Gance had met and admired), then the décor is as lush as the Italian’s prose. It looks utterly sumptuous. Emmy Lynn’s costumes are gorgeous, and everything on screen has such depth and detail that you felt as though you could reach out and feel the fabrics, the furs, the furniture, the sculpture. Fred’s lair is decked in decadent clutter: animal skins strewn over steps, throws and rugs galore, glass screens, weird ferns, cabinets with secret compartments, and “the god with golden eyes” – an oriental statue – that overlooks the ensemble. There are shadowy recesses, curtained partitions, screened-off niches – and all treated with exquisite chiaroscuro lighting and rich tinting and toning. Outside, the exteriors are just as gorgeous. My god Burel was a great cameraman! Every leaf, every blade of grass is practically three-dimensional. This is a truly stunning-looking film.

But it’s not just how good it all looks. The drama is marvellous. I love how it opens in medias res with a body on the steps, with the dog trampling across the room in panic, with the flustered Eve immediately falling into Fred’s sinister influence. And I love that the comedic character – the Marquis Groix Saint-Blaise (André Lefaur), Claire’s absurd older suitor – got real laughs in the cinema, and functioned both to puncture the air of preciousness the film might otherwise exude and to heighten the drama of the romantic entanglements. Most of all, I loved how much bite there is in every twist and turn of the narrative. Gance finds ways of making us gasp or chuckle, of drawing attention to telling details, of making these characters more than just stock villains, victims, types. I’d forgotten how fabulously slimy and sinister Jean Toulout’s character is, with his creepy haircut and louche tastes. I’d forgotten, in particular, how he looks right into the camera for a moment before shooting himself at the end of the film: with an almost triumphant smile, he defies us not to be surprised, even impressed, by his final act of will.

There are some superb close-ups, and having only experienced the film via small-screens I was unprepared for how emotionally effective these were. I had never properly seen the tears on Damor’s face; seeing them was a kind of revelation, as though the film was finally able to show me the depth of its feeling. I finally believed in Damor as a man as well as an artist, and the whole drama just clicked into place. From the outset, the sheer visual quality of the film revealed such great depth of detail to the faces that I was moved as never before. I’d always loved Emmy Lynn in this film, but it was Séverin-Mars’s performance that really struck me. He always has such intensity on screen, but he can sometimes seem to give a little too much. But in La Dixième symphonie he gets it just right: there is the right balance of emotional give-and-take, of guarding and revealing feeling. After ninety minutes of the drama, I found Damor’s final words to his wife – “Eve, I love you infinitely” – extraordinarily moving. It was not the only scene in which I found myself crying.

I must also credit much of the success of this screening to the music written by Benjamin Moussay and performed on piano (Moussay), violin (Frédéric Norel), and trumpet (Csaba Palotaï). The original score to La Dixième symphonie, cited in the opening credit sequence, was written by Michel-Maurice Lévy. So far as is known, this is lost. However, the very opening image of the film is the full-page score of the titular “Tenth Symphony”, so some of the most important music cue survives thanks to the celluloid itself. For its release on VHS, the 1986 restoration by Bambi Ballard was accompanied by an orchestral score by Amaury du Closel. The music is very nice, but I never felt it really matched the film scene by scene. It was too distant from the images, and thus never really got to grips with the emotional drama. By contrast, Moussay’s score for the 2024 screening was superbly judged. It supports the film at every stage, providing a constant melodic counterpoint to the images on screen. The narrative has a constant sense of impetus and development, of emotional depth and dramatic clarity. The arrangement for trio is beautifully balanced. The use of the trumpet provides extra sonic depth to the musical texture but is used both sparingly and sensitively.

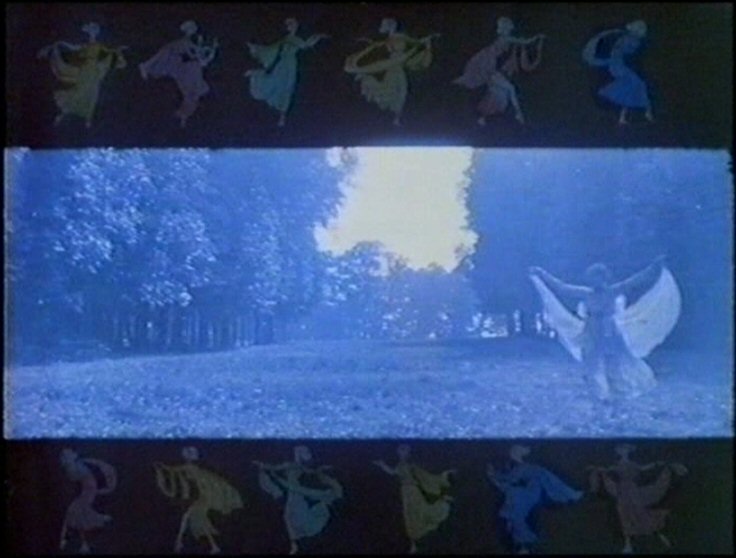

For the central performance of Damor’s symphony on screen, Moussay matches the film’s own visual instrumentation: piano and violin. Together, they offered a “symphony” that was both harmonically in touch with Beethoven while also being distinct enough to seem new: the ideal combination for this sequence. The sequence itself, in which the music is rendered visual through visions of superimposed dances (by Ariane Hugon), complete with masking and hand-coloured details, is the most well-known of the film. It’s certainly avant-garde as a cinematic conceit, though I’ve always felt that it’s couched in conventional imagery. But Gance recognizes that something needs to happen here for the point and import of Damor’s symphony to have significance. This visual music breaks out of the film, and the way Gance intercuts these visions with the enraptured expressions of the spectators creates the impression of a collective hallucination. (Much as the return of the dead at the end of J’accuse is a kind of collective hallucination.) It is this dramatic handling of the vision, more than the aesthetics of the vision itself, that is really interesting – and effective.

Though this symphony worked superbly, the scene that moved me most was earlier. When Damor discovers Eve’s supposed affair, he sits (almost falls) at the piano and his fist strikes the keyboard. In the Salle Franju screening, Moussay’s own hand struck the keyboard at precisely this moment. All the instruments had ceased playing a few moments earlier, so the piano’s single, despairing chord resonated in the total silence of the cinema. The chord died away until Damor, on screen, began feeling out a melody. Moussay, in the cinema, felt out this same melody, matching his own strokes of the keyboard to the figure on screen. It was a perfect moment. Two hands striking the same chord, a hundred years apart; two musicians, a hundred years apart, feeling out the same melody. The sense of synchronicity was both uncannily powerful and deeply moving. Live music became an act of communication, a literal reaching out of the hands to touch and revive the past. But it was also touching because of the context of the drama, for in this scene Damor feels entirely alone – deprived of the woman he loves – until he sits at the piano. Music is his solace, and he finds it not merely on screen but in the act of a live musician revivifying his creation. It’s an instance of connection, of time transcended, that only live silent cinema can provide. A truly beautiful moment.

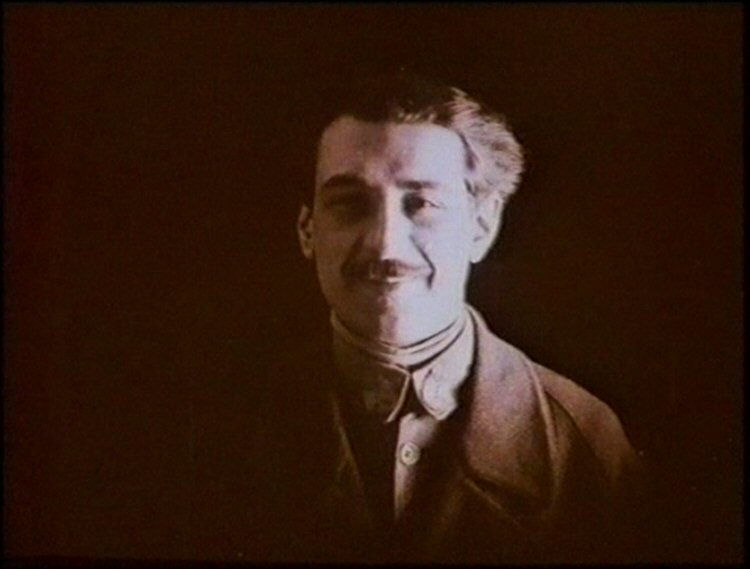

Almost as touching was the last shot of the film. After the image of Enric and Eve has faded to black, Gance himself appears under his name. This visual credit has always delighted me, but I’ve never experienced it in the cinema before. On Friday, I watched Gance turn to face the camera and smile. The audience broke into a great wave of applause just as Gance mouthed his thanks to us and smiled again. I can’t tell you how pleasing and moving this moment was: it was another instance of communication across a century of time. After seeing the creation of Damor’s symphony, we applaud the creator of La Dixième symphonie. A perfect end to a perfect screening. Bravo!

Paul Cuff