Yes, it’s that time of year again! Pordenone is once more underway, and I am not on the way to it. The furthest I’m travelling is to my study, or possibly to the living room for better Wi-Fi signal. This is because I have happily handed over my thirty euros and have my pass for the streamed content of this year’s festival. For the next ten days, I shall be posting my reviews of the digital fare on offer from Pordenone (or at least, its associated servers). Appropriately enough, Day 1 takes us to Italy for a feast of marvellous landscapes and seascapes…

We begin with Attraverso la Sicilia (c.1920; It.; unknown), one of the innumerable travelogue films produced in Italy in the first decades of the twentieth century. (This film, along with sixty others, can be found on the beautiful 2xDVD set Grand Tour Italiano, releasedby the Cineteca Bologna in 2016.) I love how even this simple film – depicting the ferry boat arriving, depositing its train, followed by a series of views of the harbour and its human and animal inhabitants – is so visually elaborate. Apart from a few shots, it is all tinted. The opening is yellow, but the first view of the little train on the ferry is orange, as though its furnace is glowing with anticipation somewhere inside it. But when it sets off it reverts to monochrome, before traversing the landscape of Sicily: the blue harbour, the orange ruins, the pink ruins, the yellow hillside. People are going about their business, a hundred years ago – and here I am, sipping my Italian coffee, a century later.

The next short, Nella conca d’oro (c.1920; It.; unknown), gives us Palermo. Palermo in blue, Palermo in pink, Palermo in gold, Palermo in split screen (postcard images, shaking in the frame), Palermo in orange, Palermo in a wash of sepia, the colour of old magazine pages. Here are centuries-old buildings, seen a century ago. Shaded colonnades from the Middle Ages, Byzantine twirls and patterns, and the people of the early twentieth century, sweeping the streets, gutting fish, building model horse and carts, wandering aimlessly. And the sea, calm, bedecked with working boats. The yellow tint a kind of oily haze upon the water, a weary warmth to the overcast sky. Flashes of leader, wobbled instructions for the printer, long dead. (It didn’t matter then, and it doesn’t matter now.) Men playing cards, not bothered by our presence. The past, cut off from its moorings a century ago and deposited on my screen. FINE.

And now, to our main feature: L’Appel du sang (1919; Fr.; Louis Mercanton). The story is based on Robert Hichens’ novel The Call of the Blood (1906), and its melodramatic plot is signalled by the title…

Emile Artois (Charles le Bargy) is a veteran writer, who has earned the enmity of his peers for his unflinching attacks on “life’s artificiality”. His friend and disciple Hermione Lester (Phyllis Neilson-Terry) lives in her villa in Rome. She confesses to him that she loves Maurice Delarey (Ivor Novello) an Englishman who had a Sicilian grandmother. Artois is jealous and comes to Rome. Seeing the lovers together and obviously happy, Artois announces that he’s going to Africa. In Sicily, the lovers – now married – spend their honeymoon at Hermione’s house on the Casa del Prete on Mount Amato, with their devoted servant Gaspare (Gabriel de Gravone). In the “garden of Paradise”, the lovers are happy – but abroad, Artois is dying of fever. Maurice and Gaspare visit the “Sirens Island”, where the fisherman Salvatore (Fortunio Lo Turco) lives with his daughter Maddalena (Desdemona Mazza). On the rocks, asleep with the fisherman, Maurice dreams of sirens – and, waking early, encounters Maddalena, half-naked in the water. Meanwhile, the dying Artois sends Hermione a letter confessing his love – and insisting that she loves him. But the doctor knows that Hermione is married, so does not send her Artois’ letter – just a telegram alerting her to his illness. Once Hermione leaves for Kairouan, Maurice grows increasingly close to Maddalena. Their romance observed by her angry father, who is content only so long as the tourists keep spending money on them. Hermione aids Artois’ recovery and they journey back to Sicily, triggering Maurice’s guilt – and desire to spend his last free moments with Maddalena at the local fair. The lovers spend the night in a hotel, while Hermione anxiously awaits Maurice at her villa. In the morning, Maurice arrives, guilty and remorseful. But he cannot bring himself to tell her the truth. Salvatore hears about his daughter’s night with Maurice and locks her in her room. Maurice writes Hermione a letter confessing the truth and saying that he knows he must leave her. Salvatore wants to meet Maurice on his island, and Gaspare plays the awkward go-between. Maurice makes Artois promise to look after Hermione if anything should happen to him. Artois intercepts a letter from Maddalena, warning Maurice – and suspects the truth. Salvatore attacks Maurice and throws him from a cliff into the sea. While Gaspare rescues the body, Artois finds Maurice’s confession – and gets the full truth from Gaspare. Artois decides to burn the letter to spare Hermione’s feelings, then goes with Gaspare to confront Salvatore and Maddalena. Artois convinces father and daughter to go to America, but Maddalena visits Maurice’s grave and is discovered there by Hermione and Gaspare. Hermione realizes the truth and goes to Artois for comfort, while Gaspare seeks revenge on Salvatore. The two men fight, but it is Maddalena who is killed by her father’s gunshot. The graves of Maddalena and Maurice lie next to one another, and Hermione leaves flowers before departing. In Rome, Hermione finds Artois’ confession, passed on from the (now deceased) doctor’s possessions, and the two are finally united. FIN.

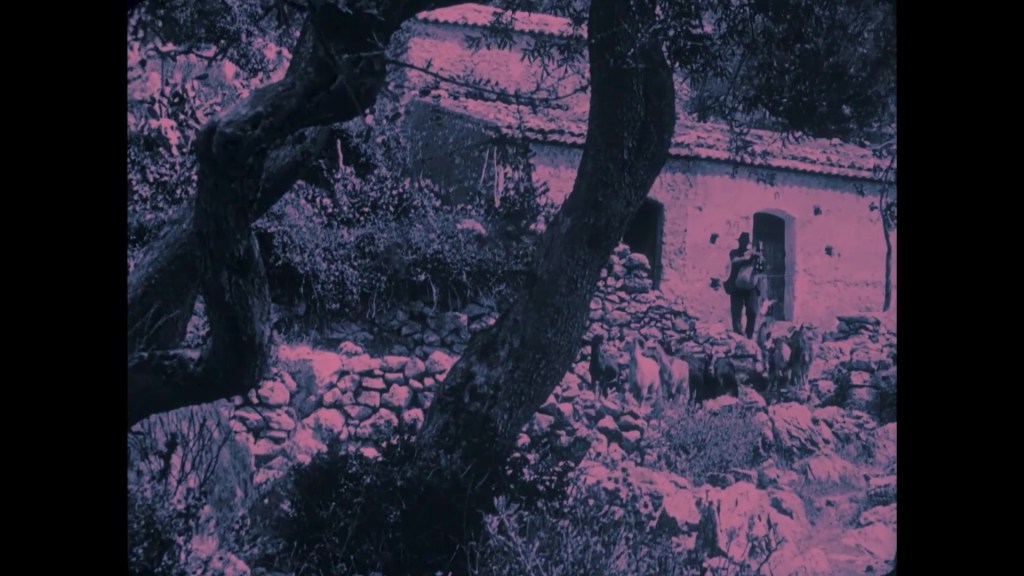

Well, well, well. First thing’s first: this is a stunning film to look at. Shot on location in Italy, the film is dominated by shot after shot of extraordinarily beautiful landscapes. The entire drama plays out against superb vistas, from views over the Colosseum in Rome to the Sicilian coastline. The whole film is also beautifully tinted and toned, from the warm gold of exterior daylight to the lustrous blue-tone-pink of evenings and the blues of nighttime exteriors. Great use is made of placing characters against these backdrops, from the terraces overlooking the landscapes to more intimate scenes along the paths and coves of the coast. The southern light is simply gorgeous, and every exterior shot of the film is a pleasure to contemplate. What an absolutely beautiful film this is.

The cast also boasts some beautiful faces. This was Ivor Novello’s first starring role, and he is strikingly beautiful in many shots – just see how the camera shows off his profile as he sits at the piano and sings, or drapes himself with open shirt across the rocks. His performance is good, but I don’t know if it’s the fault of the director or the performer that I never got a sense of depth to his character or emotions. Novello always feels slightly out of place, which suits the character – at home in Sicily without quite being Sicilian. He comes across as cutely gauche, and rather English, as he half tries to find the rhythm of the Tarantello when he first arrives on the island. In fact, he’s noticeably more convincing in his relationship with Gaspare than with either Hermione or Maddalena. The note of homoeroticism is hard to escape since the two men spend more time with each other than the married couple. Maurice goes swimming with Gaspare and his sexualized dream of sirens takes place when he is asleep with Gaspare on the rocks by the sea. Maddalena is a rival not just to Hermione, but to Gaspare: and it is the latter who tries to take revenge on Salvatore for killing his friend.

Indeed, Gabriel de Gravone was my favourite performer in the film. (Due to my decades-long obsession with Gance’s La Roue (1923), I have spent many hours watching Gravone on screen in a particular role – so I am certainly familiar with his face!) Like Novello, he is strikingly handsome – but he has an air of assurance, of physical presence, on screen that Novello never quite has for me in this film.

The rest of the cast is good, if not especially memorable. Phyllis Neilson-Terry (one of the Terry dynasty of British actors) is a strong, naturalistic lead – but her character is never given depth. I don’t think this is her fault, nor is the dullness of Charle le Bargy’s Artois; the film simply isn’t able to shape their performances or deepen their characters. Maddalena’s death, for example, is shocking – but as an act, as an event, not because I cared for (or even particularly knew or understood) her character or relationship with Maurice.

My reservations about character and performance stems, I think, from the fact that the film lacks dramatic depth. For a melodrama, even if my brain isn’t overly engaged, my heart needs to get involved: I wanted and needed to feel more from this film. It’s very, very good looking, but that’s not enough. I was purring over the landscapes, but never about the characters. Louis Mercanton is good at framing the drama against the landscapes, but his camera never gets too close to his characters. Perhaps overly conscious of showing the backdrop, there are virtually no close-ups – we are quite literally kept at a certain distance from the characters. Even so, there are other ways to create depth and complexity. Mercanton can compose a shot, and organize a sequence, but nothing ever quite builds to a single image or shot that grabs the heart or contains any kind of emotional or psychological revelation. There were no scenes where the staging struck me as being especially imaginative or striking. The fair, during which Maurice and Maddalena spend the night together, is perhaps the most dramatic of the film, with its red tinting and the lovers in silhouette at the balcony window. But this, too, is a series of pretty images rather than a fully integrated dramatic montage. (I think, inevitably, of a similar sequence in Gance’s contemporary J’accuse!, in which illicit lovers encounter one another at night during a firelit farandole – a sequence that is filled with (more) striking images and a rhythmic crescendo.) Ultimately, I was more impressed by Emile Pierre’s photography than Mercanton’s direction.

So that was Day One. Whatever my reservations, I’m very glad to have seen L’Appel du sang. It’s one of the best-looking films (I was about to say “prints”, but I suppose that’s not quite true) I’ve seen in a while, and the tinting and toning of the landscapes was a particular pleasure. But I also particularly appreciated the Italian shorts that preceded the feature. They introduced us to the period and place in which L’Appel du sang is set. Aside from compilation DVDs, such short films can be difficult to present convincingly – so slipping them into a programme in such a pertinent way is a nice touch. Seeing these three films together was a delight. A very nice way to start the festival.

Paul Cuff