Day 6 returns us to South America. We begin with a Brazilian comic skit, then cross the sea to Cuba for a drama of the land, the law, and thwarted love…

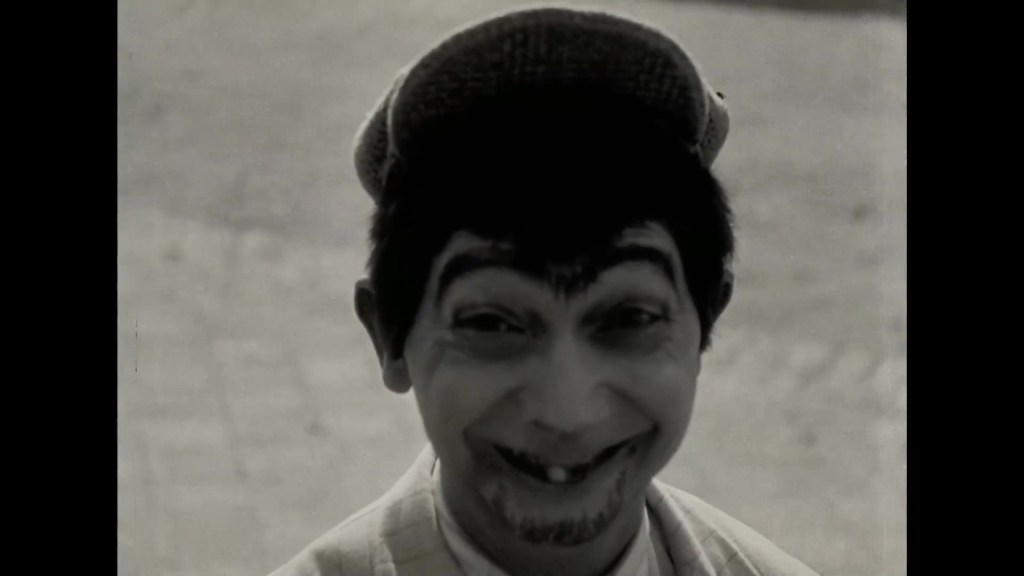

Our aperitif is Apuros do Genésio (1940; Br.; unknown), “a cinematic gag”. What a strange little film. Our hero, the initially unnamed Genésio Arruda, tries to woo a girl but is chased by a brutish rival – along a road, through the streets, until it occurs to him to simply exhale and blow the rival backwards. The film reverses and the rival, together with traffic and time itself, recoils and retreats. He grins with his almost chinless grin, wispy beard and thick monobrow, and the film ends. But not quite. For every so often, the film has been cutting back to a cinema audience laughing at, we presume, the film that we are watching. And when the film ends and we see the audience again, the film cuts to the cinema exterior – crowds of people milling around, looking at us. The intertitles become an advert for Genésio Arruda’s “crazy shows” – a forthcoming attraction, lost to time.

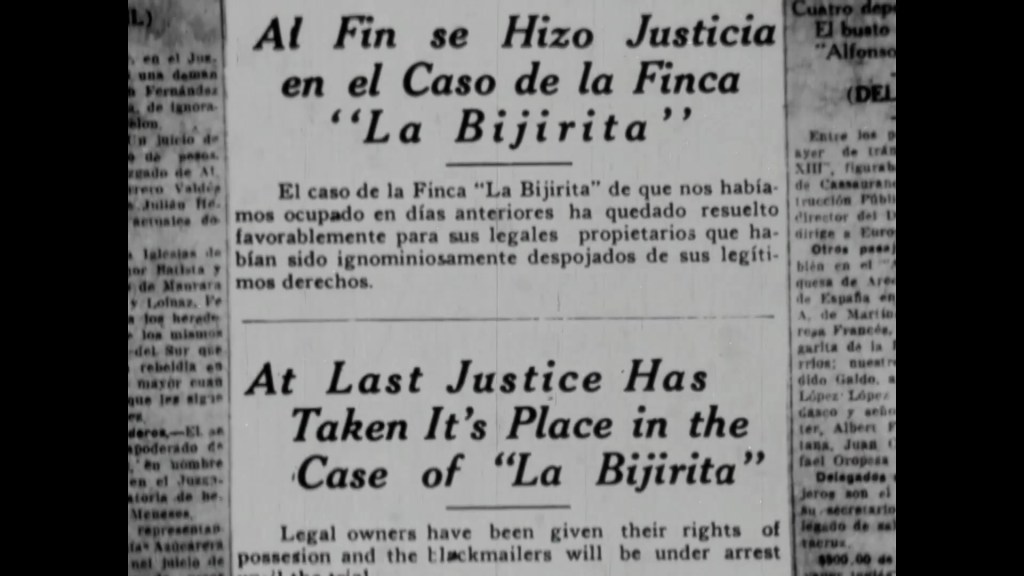

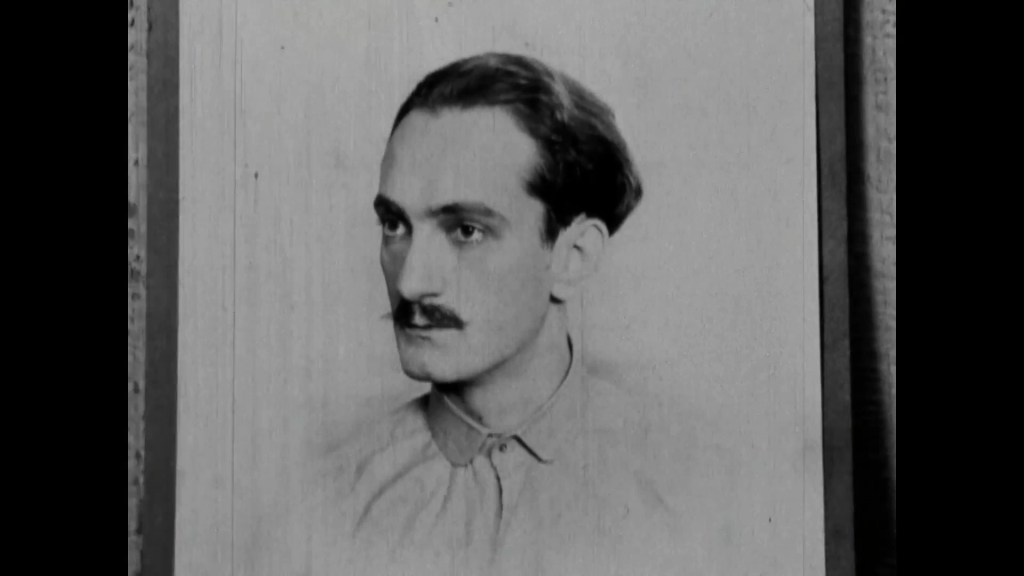

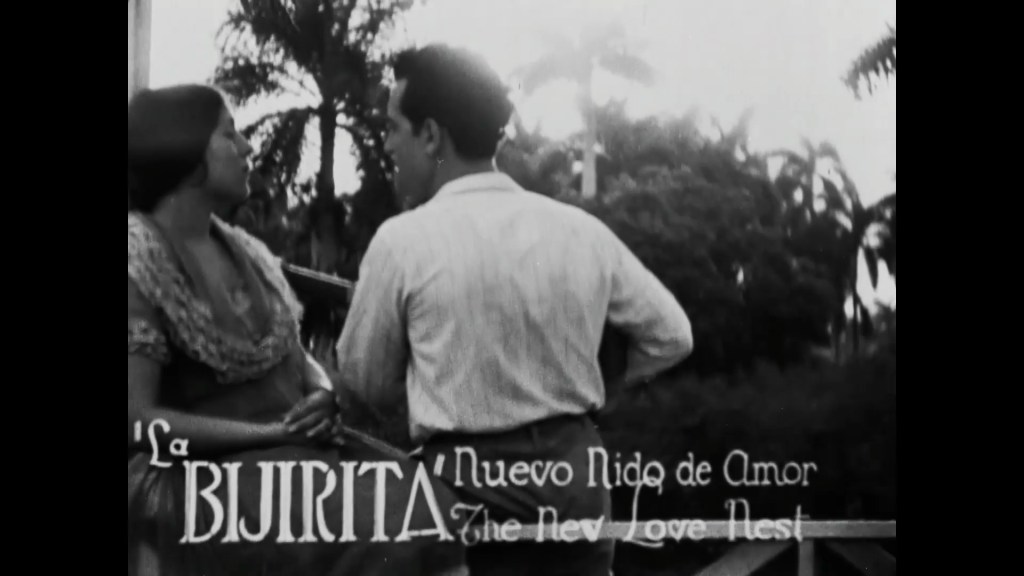

And now for our feature: La virgen de la Caridad (1930; Cu.; Ramón Peón). The Cuban press, reflecting “the pulse of the nation”, recalls the case of “La Bijirita”… We are introduced to Yeyo and his grandmother Ritica, who is “always thinking of sadnesses”, polishing the frame of the film’s titular Virgin. A flashback to her husband, who fell fighting for the freedom of Cuba. To cheer themselves up, they go to a party hosted by Canuto and his daughter Rufina. We meet Hortensio, a soldier, Rufina’s sweetheart, as well as Don Pedro and his daughter Rufina. Yeyo and Trina are in love, but her father is against the match. Meanwhile, Matias Delgado (who “brings a dark cloud, foreboding evil” to the land) picks a fight with one of Yeyo’s farmworkers, and Yeyo must intervene. Matias finds an ally in the form of Fernandez, a smarmy, snappily-dressed cattle owner. At a fiesta, Fernandez sees Rufina and starts to charm Don Pedro. Though Yeyo wins the riding tournament, Don Pedro objects to his flirting with Rufina. Meanwhile, it is revealed that La Bijirita once belonged to Fernandez’s father. Matias says that the farm could return to his ownership, since the legal papers of Yeyo and Ritica are bound to have been destroyed in the war. The pair bribe some officials and Fernandez “sells” the farm to Matias. Fernandez boasts of his sale to Don Pedro, but Trina senses trouble. Fernandez confronts Yeyo and Ritica, who remind Fernandez that his father sold them the farm. But they have no paperwork, and the pair are evicted. To make matters worse, Rufina warns Yeyo that Trina and Fernandez are being hastily married. Ritica counsels him to “be resigned” and kneel before the Virgin. He does so, just as the workman is knocking through a nail. The painting falls and (yes, you’ve guessed it as soon as you saw the name of the film) the deeds of ownership fall from the back of the painting. Yeyo rushes to the wedding with the proof of Fernandez’s forgery. Don Pedro turns against Fernandez and accepts Yeyo as the rightful man for Trina. Yeyo thanks the “miracle” of the virgin. The lovers return to the happiness of life on their farm. FIN.

This was my first Cuban silent, and I enjoyed it. The film is shot entirely on location, and it takes great pleasure (and time) in showing us the land. The opening party begins with a mouthwatering montage of food preparation – the care and attention of the locals for their produce and their cooking. And we also see the gradual arrival of the guests, the slow lanes, the carts and horses of this world. With very simple means, we see the community and what characterizes their world and relationships. Later on, too, there are slow travelling shots that show off the landscape: the journey to the party, Fernandez’s arrival to the station, the race to the rescue along the dusty roads.

Though La virgen de la Caridad is by no means an exercise in cinematic flair, it uses close-ups and soft focus, a variety of shot lengths and angles, careful framing and dissolves, to great effect. What perhaps stand out most are some very effective tracking shots at dramatic moments: Rufina’s hesitant entry to greet her father and Fernandez; Yeyo confronting Fernandez and his lawyers when they take his farm; the move to reveal the partition wall where the painting falls; Yeyo arriving at the wedding. In particular, the whole race-to-the-rescue sequence is textbook D.W. Griffith: it takes place on horseback, and the horse even gets waylaid by a train en route. However cliched a device, it makes for a deeply satisfying ending – especially that final tracking shot as Yeyo marches into the municipal office brandishing his proof.

The lead cast are also very good. There is a sense that these are real people who live and work and tend the world in which we see them. If there is no great depth to any of the characters, they are all well-defined and believable. The central lovers – played by Miguel Santos and Diana Marde – are convincing together. Marde, in particular, gets some great close-ups in which her flashing glance shows us quickly and succinctly just what’s she’s thinking and feeling. Matias, Fernandez, and Don Pedro are less complex characters, but the cast do just what’s needed to make you understand their motives and feel something about them – even if that’s just a sense of outrage, or a desire to wipe that smug look of Fernandez’s face.

There is also a sense of the past, both personal and political, that La virgen de la Caridad creates through the figure of the missing father – glimpsed in flashbacks at the start and end of the film. Though a specific time and date is never mentioned, Yeyo’s father presumably died before or during the war of 1898, fighting Spanish rule. The sense of belonging that Yeyo and Ritica feel for their farm thus has broader, national/political, connotations. Reclaiming the land is not just a local issue, but a Cuban one. The son and his mother are only small-scale landowners, dressed and housed very simply – unlike the dapper Fernandez. Yeyo rides by horse, whereas Fernandez arrives on the train. Yeyo represents someone who has lived and worked on the land, someone who it is easier to sympathize with than richer landowners – people who buy and sell the land without ever tending it. All of this context is present throughout the film, but I never felt that I was being lectured. Very succinctly and effectively, the film provides a history for its characters that taps into a broader national history. As someone who knows very little about Cuban history, I felt that I was given enough information to fill out this past – but I never felt that I was being lectured, or that the film was serving an ideology more than constructing a drama.

I must also mention the music, by Daan van den Hurk, which added some pleasing Cuba rhythms to the piano accompaniment – as well as the occasional use of other instruments to fill out the texture and suggest mood and location. All in all, an enjoyable and satisfying watch.

That was Day 6, and I very much enjoyed the return to South America. Apuros do Genésio was fun enough, and I’m curious to know how contemporary audiences saw it. In 1940, was this silent trailer already an aesthetic oddity? The cutaways to the audience suggests a self-awareness of form, as well as the sense that form itself might be an object of curiosity or humour. Is the film a genuine silent comedy skit, or an ironic pastiche of one? In 1940, it might conceivably still be both. Either way, it’s a pleasingly odd morsel and I’m glad it got included in the programme. As for the main feature, La virgen de la Caridad is no masterpiece of the cinema, but it is a very effective drama in a rich setting. Though the print was not the best quality (the restoration credits state that it is the only version available), you could sense the land and its past on screen, and I found it an engrossing film to watch. A good day.

Paul Cuff