Having written last time about films featuring the Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria-Hungary, this week we turn to a rival power in the Balkans: Serbia. In 1904, Peter Karađorđević was crowned as King Peter I of Serbia. His reign is seen as a kind of golden age of Serbian development in the region, as well as the locus of tragedy and triumph in the Great War. I had seen plenty of images from Serbia in the war, but the existence of footage taken at the time of Peter’s coronation was new to me. Thanks to a DVD from the Yugoslav film archive, we can see the surviving material filmed by Frank S. Mottershaw in 1904. Mottershaw’s father, confusing also named Frank Mottershaw, had founded his Sheffield Photo Company in 1900 and the spent the next decade making a number of inventive short films that experimented with new forms of editing, especially the “chase” format – as exemplified by the marvellous A Daring Daylight Burglary (1903). In 1904, Frank’s son journeyed to Serbia in the company of Arnold Muir Wilson, a lawyer and journalist – and honorary Consul of the Kingdom of Serbia. They went to film events around the coronation of Peter I. Though the film’s title implies a record of the actual coronation, Mottershaw and Wilson did something rather more interesting. The film’s subtitle in more accurate, and more revealing: “a Ride through Serbia, Novi-Bazaar, Montenegro, and Dalmatia”. This, then, is what we get…

Street views of Belgrade, April 1904. The past walks past us, gazes back at us. Children, as they do everywhere in the past, stop and stare, grinning, waving, poking their noses into the frame. Here is the world as it was before the Great War, populated by the faces of those who would live through it. There are soldiers and officers and priests and march pasts. But there are also ordinary people, civilians going about their business, or waiting, or mooching aimlessly.

The royal procession, captured at an arrestingly odd angle: the camera is tilted, as though craning its neck to see the dignitaries. There they go, in splendid full-dress uniforms: caped, and plumed, and epauletted. There are carriages of women in big hats. Men raise their own hats in salute. Dignitaries in top hats, in bicornes. There is no view of the coronation, not even a glimpse of the cathedral. We wait outside, in the streets, with the crowd. We see the parade returning from the cathedral. It is less grand, and curious dogs, oblivious to the progress of state history, dart out amid the lines of slow-marching men and horses. There are long shadows and pennants and musicians (and lumps of horseshit on the cobbled street). A man who may be the king rides past. Others are more arresting, since they pass close by to the camera, momentarily filling the frame with their presence. Who are they? What became of them? More carriages roll past. The crowd mills about. The pleasures are slow. No-one is in a hurry. It’s a free show. Just stop and stare at it all. The cavalry glance guardedly to their right. The musicians are no longer playing, they examine their instruments as they pass. Now the crowd breaks up and the street fills with the bustle of everyday life.

Another parade, this time celebrating the “development of the Serbian army” across history. So a historical parade about the history of historical parades. The camera watches as it passes. Rank after rank, often just gaggle after gaggle, of soldiers in historical dress, growing more modern. Here comes the first artillery, then marching bands, then modern guns, smarter ranks, better-drilled ranks.

Views of Belgrade port and fortress. The past seeped in a golden haze, the haze of a distant spring, a spring of empty expanses, cold light. Now views of the Serbian army on parade. The army has room to stretch its formations, out across the muddy plains. The camera watches. There they go, the men, the horses – and the little dogs who once more run after the moving ranks. Odd figures wander in front of the camera then vanish. The past stops and restarts and vanishes. The guns roll along, but there is no chronology here, just a series of unending and thens… And then the officers dismount. And then the carriages appear. And then the priests scratch their beards. And then…

And then, Žiča monastery. A beautiful snapshot of an eastern Europe I know from innumerable books and photographs of the war-torn century. Here are the whitewashed walls (a little greyed), the Romanesque arches, the rounded cupolas topped with Orthodox crosses, the priests in their long dark robes and tall hats. (And the curious youths.)

Studenica monastery. The camera turns its head to follow the progress of a carriage. A stunning valley stretches out toward the hazy horizon. The walls, the doors, the shadows. I can see spring warming up. The sun is brighter, casting darker shadows across the forested valley and steep slopes. Horses stand around. The world is sometimes stunningly empty, sometimes observed only by us.

Kraljevo market. Pigs and sheep, an array of carts. The camera pans nearly 360-degrees, and everywhere it turns are people who stop and stare. Is this the first moving picture camera they have seen? Novi-Bazaar, and everyone stares again. The camera turns on its axis, and every frame is filled with curious life, streets I want to walk down, houses where the past resides. The people on the streets here are more casual, just as curious, more liable to smile, to mill around, to ask questions – finally, to bring their wives and children and approach. (The children are smoking.)

The Montenegrin army. I recognize their uniforms from the endless books about the Great War that I collected as a child. (Yes, this corner of the world is somehow more familiar to me in its past form, more known to me in its old clothes, as this generation and the next.)

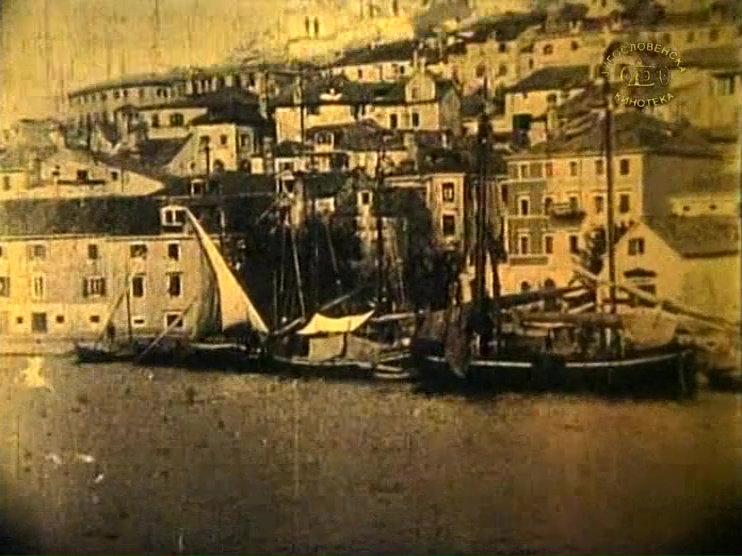

Views of Šibenik. A large ship, the dock, and smaller sailboats. Women carry huge barrels on their heads. The water glimmers in the sun. the camera turns to marvel at the houses, shoulder-to-shoulder, then suddenly floats aboard a ship. We go to Zadar, we float past ancient walls, we drift… THE END.

This film is on DVD via the Yugoslav film archive, and its material history – passing from the UK to Serbia in 1937, being shown sporadically until its restoration in 1995 – is summarized in the opening titles. The main intertitles were based on Wilson’s notes, so are a modern interpolation into the film. It has no soundtrack, but the images speak for themselves – or rather, they remain stubbornly, eternally silent. As such, they are all the more evocative. I’d love to know more about how and when it was shown in Serbia, and what kind of audiences saw it. The opening credits inform us that the film was exhibited in the UK as part of Wilson’s lecture series on Serbia, then in April 1905 shown at the National Theatre in Belgrade in the presence of King Peter, royal family, and other dignitaries. How was it presented there? With music? With narration? And was it shown outside of this one projection? Where? And when? Did the people on screen, the men and women and children who gaze back at us, ever get to gaze back at themselves?

The Coronation of King Peter the First is a great curiosity. It’s not in great shape, it shows its age, it bears the marks of its material history. It’s awkward and faintly shabby. But it’s also very beautiful and very suggestive. It has a tremendous aura of its past, of Serbia’s past, of Europe’s past.

Paul Cuff