This week, I’m off to another film festival, this time hosted by the Bo’ness Hippodrome in Scotland. Did I say “off”? I mean… well, what do I mean? What adverb suggests staying in my study? I suppose I’m “in” to another film festival. This is my first experience of HippFest, which has been on my radar for some years. I’m also pleased that the online version of this festival has its own name. “HippFest at Home” sounds delightful, a union of being away and being where I am.

The pre-film introductions – from Alison Strauss (Arts Development Officer and HippFest Director for Falkirk Council), Magnus Rosborn (Film archivist from the Swedish Film Institute), and Lisa Hoen (Director of the Tromsø International Film Festival) – were also exceedingly welcoming. My only experience of pre-film introductions at online festivals comes from Pordenone, where the videos are pre-recorded and loaded as separate (and optional) prefaces to the films themselves. At HippFest, the introductions are those given live in situ – filmed and included as part of the single video that encompasses the evening’s programme. It does not force you to watch them (one can always fast-forward), but it encourages you to do so by having them as part of the same video timeline. Unlike Pordenone, where I almost always end up skipping the introductions (purely for the sake of time), I watched all three speakers for this HippFest programme. The video stream is perfect: we get explanatory text to see the names of everyone on screen, and the camera is placed so that we feel like we are part of the audience they are addressing. Indeed, Strauss’s introduction to the festival explicitly welcomed online viewers. The speakers themselves covered issues curatorial and practical (Strauss spoke about HippFest and her interest in tonight’s film), restorative (Rosborn spoke about the film’s rediscovery and reconstruction), and cultural (Hoen spoke about the context of the Sámi people who are the film’s subject). Hoen also explained something about the motives and context of the musicians who accompanied the film, as well as introducing the musicians themselves. I can only say that I found all three introductions engaging and informative. This really was the ideal way to start the programme.

Med ackja och ren i Inka Läntas vinterland (1926; Sw.; Erik Bergström)

So, here is our feature film, “With Reindeer and Sled in Inka Länta’s Winterland”. The film is a portrait of life in the snowbound landscape of northern Sweden. We follow Inka Länta, who lives with her brother and maternal aunt, and next door to her maternal uncle Petter Rassa and his children. We also meet Guttorm, from a nearby (20km away) camp. We follow them as feed their family and animals, as they go to market at Jokkmokk, as they track reindeer, as they make and unmake their tents and camp, as they hunt wolves, as they slaughter deer.

From its first images, a hypnotically beautiful panning shot around snow-covered trees, this film is a visual treat. Indeed, these first shots are among the most beautiful in the film. Complete with a delicate toning that turns the shadows a delicious deep blue-green, these are the most ravishing snowbound trees you’ve ever seen. When the camera gently tracks through the landscape, and this astonishing world begins to open out, I was incredibly moved – just by the sight of it, by the sensation of moving through stillness. My god, my god, my god, what a beautiful sequence. Cameraman Gustaf Boge captures the cold winter light with extraordinary skill. When (after several unpeopled shots) we see Guttorm wading through knee-deep snow, the light throwing his shadow before him, with the forest behind him, this is more than a mere “documentary” scene – it’s a kind of journey in space and time, a distillation of some unreachable moment in the past. The stillness of this wintry light and powdery shadow, the way that the snow itself exists in a kind of arrested physical state… goodness, it’s as perfect a glimpse of some archetypical winter as you could imagine. And yes, the silence of it is part of (essential to) the hypnotic perfection of these scenes.

But the film is as much about the difficulties of life in this landscape as it is about its beauty. For all the beauty of the snow, the trees, the vistas over endless ice, you also see what it takes to live here. The scene inside the tent when the family eats is amazing for the way the whole frame fills with the smoke from the fire, the steam from the pots, and the breath of the inhabitants. The film shows us the effort in doing everything here: from moving through snowdrifts (by foot, by ski, by sleigh) to herding livestock.

In particular, there is an extraordinary sequence in which Petter hunts, chases, shoots, kills, and skins a wolf. We watch the wolf bounding over the snow, while Petter slogs (even on skis) at high speed in pursuit. Only after several shots cutting between wolf and hunter do the two appear in the same frame. The first thing we see after the wolf has been shot is Petter mopping the sweat from his face. It’s an exhausting scene to watch, and the filmmakers make sure you realize how exhausting it was to perform. I say “perform”, because everything here may have the manner of documentary but it is all too well organized, too well filmed, and (in detail) too narratively dramatic to be truly “non-fiction”. Petter’s pursuit of the wolf is remarkable, and clearly real in the sense that he does indeed pursue and kill the wolf, but the skill of the filmmaking is just as impressive. Petter skins the wolf and leaves its body hanging from a wooden frame (I was about to say gibbet), and then he and his comrade move away into the distance. Every action is realistic, but the neatness of the framing and composition, the clarity of the montage of the sequence, bears all the hallmarks of a different kind of narrative filmmaking. This is a very beautifully organized version of reality.

As the evening’s introductions made clear, this is part documentary and part fiction. (And, as Huen highlighted, there is a whole cultural and ethical side to the treatment of the Sámi people that the film deliberately erases.) Though there are clearly scenes of documentary reality, capturing real people and places (especially the market sequence) others (like the climactic sleigh accident) are staged events. This balance caught me a little off-guard, and I wasn’t sure whether I was being moved by the reality of the events or their fiction. At the end of the film, we see an accident in which Länta’s brother dies. Intertitles tell us that Länta must now leave her family and her homeland. She begins a trek across the open ice, and the film gives us flashbacks to earlier scenes with her family. But then Guttorm reappears and “hearts speak” and Länta returns to the hills, and to “happiness”. The sequence works, I think, because of the balance between the reality of the world we have seen (and, yes, its sheer beauty on screen) and the fictional framing of characters and events. Länta is a real enough presence on screen that, however contrived the events around her, I was sad at the thought of her life falling apart. And her world is real, too. I had spent the last hour in a kind of trance-like state of wonder at this world, so the thought of Länta leaving it (and my leaving it with her at the end of the film) carried its own sadness. So I gave a free pass to the abruptness of the ending, and the contrived nature of the narrative, and found myself moved. Why not?

I must also mention the music, by Lávre Johan Eira, Hildá Länsman, Tuomas Norvio, and Svante Henryson. Many of these musicians come from or have roots in the Sámi culture, and their score for this film is a blend of traditional and contemporary sounds. It’s a compelling combination of dreamy synth washes, rumbling electric guitar chords, and chant. While some of it worked very well (especially the opening scenes), other sections of it were too busy for my liking, falling out of rhythm with the images. But I appreciate that this kind of film (light on narrative incident and character psychology) is exceedingly difficult to write music for, and perhaps necessitates a more experimental approach. (To give you an impression of what the score is like, I cannot do better than quote the sound-description text that is an optional accompaniment to the film: “Dog noises, ruff, woof. Low vocal continue to talk like a wise old man. [….] Light dinging like a railway crossing in the distance. […] Babbling vocals continue. […] Frenzied scene of muttering vocal layers interweaving with busy backdrop of activity, metallic sweeps and glassy punctuations.” And, later: “Sweet melodies and dreamscape backdrop of echoing synths and waves of sound continue to ring out.” Kudos to whoever assembled this text, it’s really rather wonderful.) By the end of the film, I was absorbed in the soundscape as in the images.

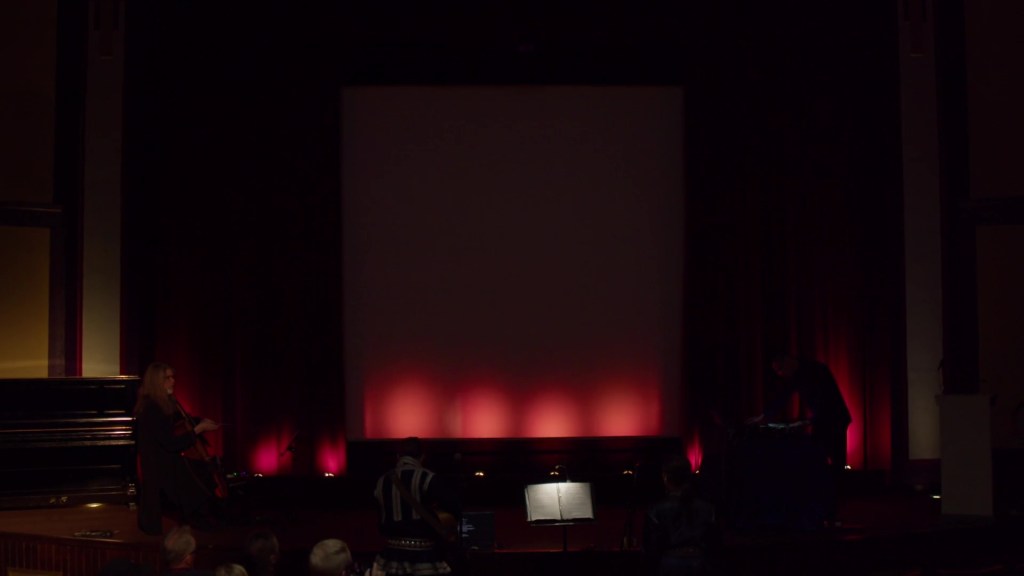

Finally, a word on the online options for this HippFest at Home presentation. There are two ways provided to watch the film. In the first, we get to see the film and the musicians: a split screen arrangement allows us to watch both at the same time. I’ve seen this approach in some youtube videos in the past, but this was better composed and lit. I’ve often thought that this would be an ideal option on any/all home media releases of silent films: seeing musicians live with the film was always (and remains always) a key part of the experience. The other option provided by HippFest at Home is to watch the film without seeing the musicians. But even in this version, we get to see the musicians at the end of the film and see and hear the audience applaud. In each case, it’s wonderful to be able to see the musicians, and glimpse the audience as well. As with the introductions at the start, this presentation made me feel a participant in the event. It’s a superb presentation.

What else can I say? This was a superb programme, superbly presented. Bravo to everyone involved. Already, I feel that HippFest at Home is the most enjoyable format for an online festival that I have experienced. While I know that I’m not really there, and that I’m watching everything over a day after the event has happened, the presentation bridges this geographical and temporal gap. I’ve never before truly felt like I was at a festival before, but here I do. I absolutely cannot wait to join in with tomorrow’s show.

Paul Cuff