This week, we foray to China for a thick slice of melodrama. Love and Duty boasts two of Chinese cinema’s biggest stars of the period, Ruan Lingyu and Jin Yan, and a sprawling narrative of numerous twists and turns. But before I discuss the film, I must provide some little context for how I came upon it and why I have not watched it until now…

Love and Duty has sat on my shelf since September 2022. The previous month, I had applied for a job lecturing film history at a university. I had not occupied an academic position for some time and had essentially abandoned thoughts of doing so. But the modules I would be teaching at this position overlapped perfectly with my interests and past experience. Despite the overwhelming likelihood of failure, and the gruelling tedium of filling in online forms, I began the process of applying. (My god how I hate job applications.)

Conscious that I should expand my knowledge of the wider culture of silent cinema (and show evidence thereof), I set out on a spending spree. I bought a stack of books, DVDs, Blu-rays. I also downloaded a slew of articles, desperate to convince myself that I was au courant with the latest scholarship – or at least up to date with what I might have missed. I viewed, I read, I wrote. Within a month, I completed and submitted an article to a scholarly journal as well as submitting my application. It was a frenzy, but I was buoyed by the rush of it all. Was the chance of success really so remote? I guzzled at the trough of irrational optimism. I planned out modules, I compiled reading lists. After all, I might need to show at an interview that I had thought ahead about how to shape the curriculum. I genuinely enjoyed imagining course outlines and formatting reading lists.

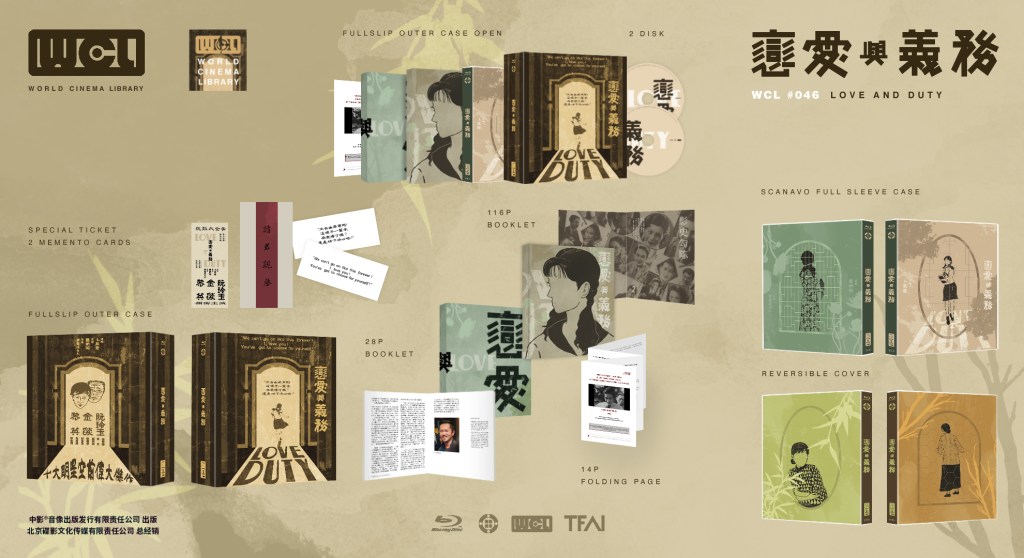

First on my hit-list was a tranche of Chinese silent films and literature thereon. Packages arrived, digital material was carefully downloaded, labelled, filed. Since not many Chinese silents are available on DVD/Blu-ray, I was especially keen to get hold of the best edition then available. Step forward, Love and Duty. An “exclusive limited edition” of this film happened to have been released in China by the World Cinema Library label in the summer of 2022. Only 700 copies were produced, and they were very difficult to obtain if you didn’t know in advance and could preorder. I did not know and did not preorder. I therefore had to find a copy via an online store I had never used, based in Hong Kong. I also paid a good chunk more for the privilege, and waited in anxious expectation that I had been conned and would receive nothing – or perhaps that I would receive a message from my bank that I had been drained of all the money I possessed. But why worry? The salary of a lecturer would of course make up for any short-term losses. (Here I may have struck a Douglas Fairbanks-style pose, hands on hips, and thrown back my head in boisterous laughter.)

While the disc was on its way from Hong Kong, I received an update about my job application. I had fallen at the first hurdle. For many reasons, I knew (or very strongly suspected) that this would be the case. But that did not lessen the dispiriting sensation of the news. (Such emails are tactfully generic and never state the reasons for one’s rejection.) A few days later, the special edition of Love and Duty duly arrived. Everything was as promised. The cellophane gleamed around its imposing bulk. I added it to the expensive pile of hubristic purchases. Here was a hefty tome from Italy, there an overpriced edition from France, elsewhere a set of German films without adequate subtitles. And atop them all was Love and Duty, the single most expensive Blu-ray I owned. I put away my purchases. Life resumed. (Canny readers may realize that it was at this point in my life that I began this very blog.)

Perhaps the effort of the application and its inevitably disappointing punchline put me off watching Love and Duty for so long since then. Why revisit my folly? Well, nearly three years later, my decision to watch this film in 2025 was entirely spur-of-the-moment, precipitated by nothing more than the unexpected prospect of a free evening. Why not take the plunge and watch the bloody thing?

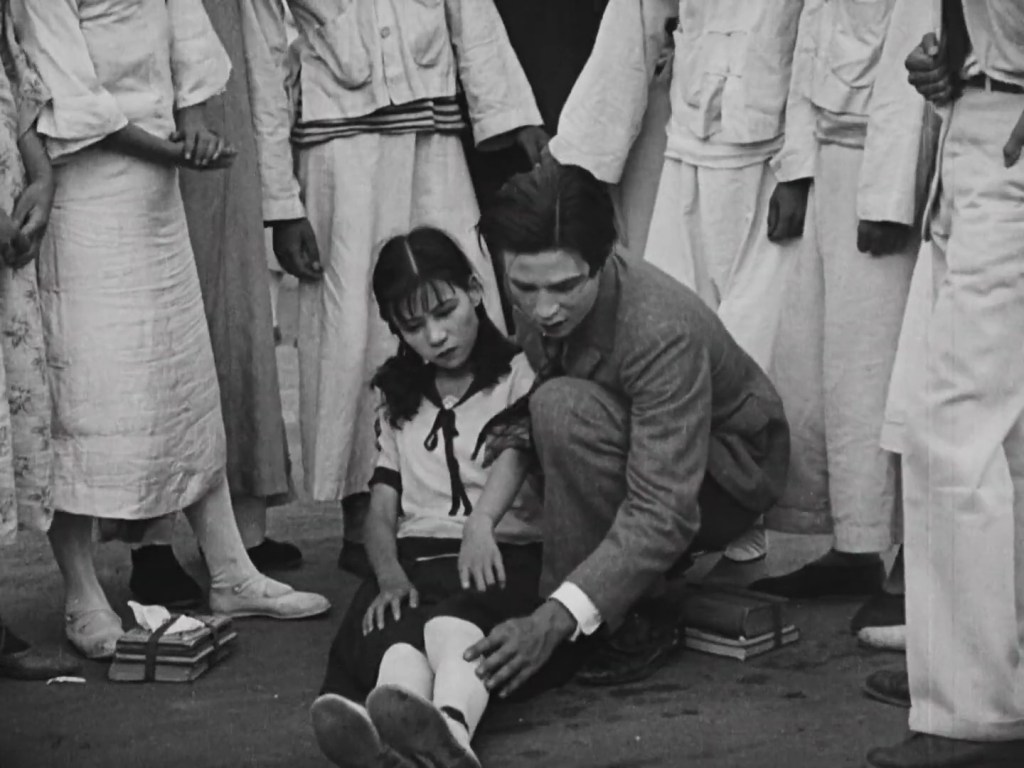

Love and Duty is set in Kiangwan, near Shanghai, where the student Li Tsu Yi encounters and falls for Yang Nei Fang. After aiding her when she is wounded in a car accident, Tsu Yi and Nei Fang exchange tokens of love. But Nei Fang’s father has already arranged his daughter’s marriage to the successful Huang Ta Jen. They duly marry, and their joyless union produces two children. Years pass, then Nei Fang and Tsu Yi meet again by chance and resume their relationship. (Ta Jen, meanwhile, is being pursued by another woman.) Eventually, Nei Fang leaves her husband for Tsu Yi – but the latter doesn’t allow her to bring her children. Despite their initial happiness, Nei Fang and Tsu Yi are soon dogged by rumour. Overwork exacerbates Tsu Yi’s (previously undisclosed) illness, and he dies – leaving Nei Fang to take care of their new daughter, Ping Erh. More years pass and Nei Fang encounters her first two children, who are now young adults. Drawn by chance into their existence, but ashamed to reveal her identity, she decides to end her life and commend Ping Erh into the care of Ta Jen. Moved by this sacrifice, Ta Jen welcomes Ping Erh into his family and instructs his children to respect the memory of Nei Fang.

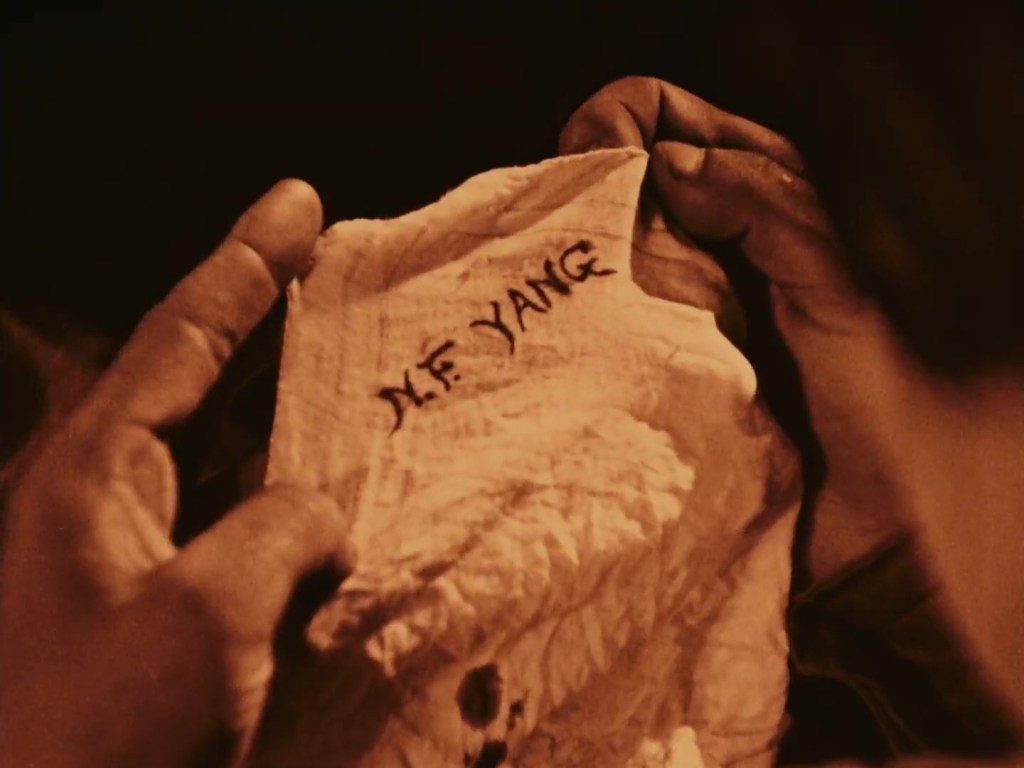

Well, I said this was a melodrama – and boy does it live up to its genre. Its contrast of familial duty and romantic longing, its intergenerational conflict, its rescues-from-the-water, its sudden illnesses, rapid ageing, premature deaths, and its concluding aura of saintly forgiveness are all familiar tropes. Love and Duty carries them all off with aplomb. There are also plenty of interesting touches that make the drama more sophisticated than simply a genre piece. The film is filled with interesting pairings, doublings, echoes: the lovers v. the married couple, the husband’s own interest in another woman; the two families of (half-)siblings, the two generations of paired sweethearts. Even the figures who remain constant between past and present (the husband, the servant) echo their past actions. Years after his first spreading of malicious rumour, the servant (called Fox) once more seizes the chance to spread gossip (thus bringing about more unhappiness), while Ta Jen repeats his vindictive behaviour – only to realize the damage his actions have done in the final scenes. (Here, the character’s somewhat weedy nature becomes a kind of moral strength: Ta Jen knows that Nei Fang has undergone great suffering, and his tears are genuine. Ta Jen’s earlier toughness seemed more the product of social pressure than genuine hatred. He is a small, almost comically unheroic figure, with his round glasses and prim moustache. At the end of the film, I readily accepted that this man could feel sorrow and acceptance.) There are also repeated gestures, like the holding of handkerchiefs as tokens of exchange, both when the lovers first touch after the accident and then again after the accident with Fei Nang’s first child. Likewise, in the latter scene, the way that Nei Fang revives the child after Tsu Yi rescues them from the water is repeated much later when she tries to revive the dying Tsu Yi. Or the writing of the note when Nei Fang leaves her husband, echoed in her sending him her suicide note at the end. Negotiating such a long film, and a long narrative within the film, is made easier and more effective by such means.

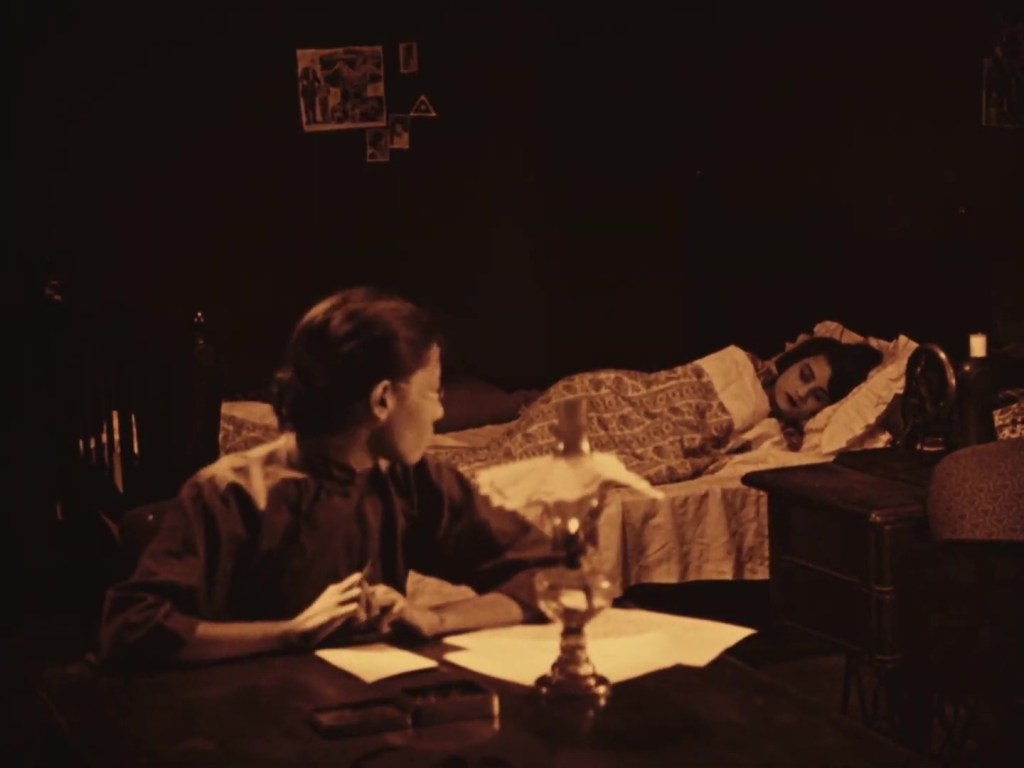

Central to the film’s success is Ruan Lingyu as Nei Fang. She carries all the emotional weight of the film. Having touched on the doublings that the film uses so often, it must be pointed out that Ruan Lingyu plays both the mother and the (grown-up) daughter from her first marriage in the later stages of the film. The in-camera trick of re-exposing one shot allows both characters (i.e. the same performer) to appear in a single frame, apparently interacting with each other. They face each other, but the effect is one of contrast as much as mirroring. The child now resembles Nei Fang at the beginning of the film, while Nei Fang herself has aged well beyond her years. Ruan Lingyu is marvellously committed, always engaging – always a presence on screen.

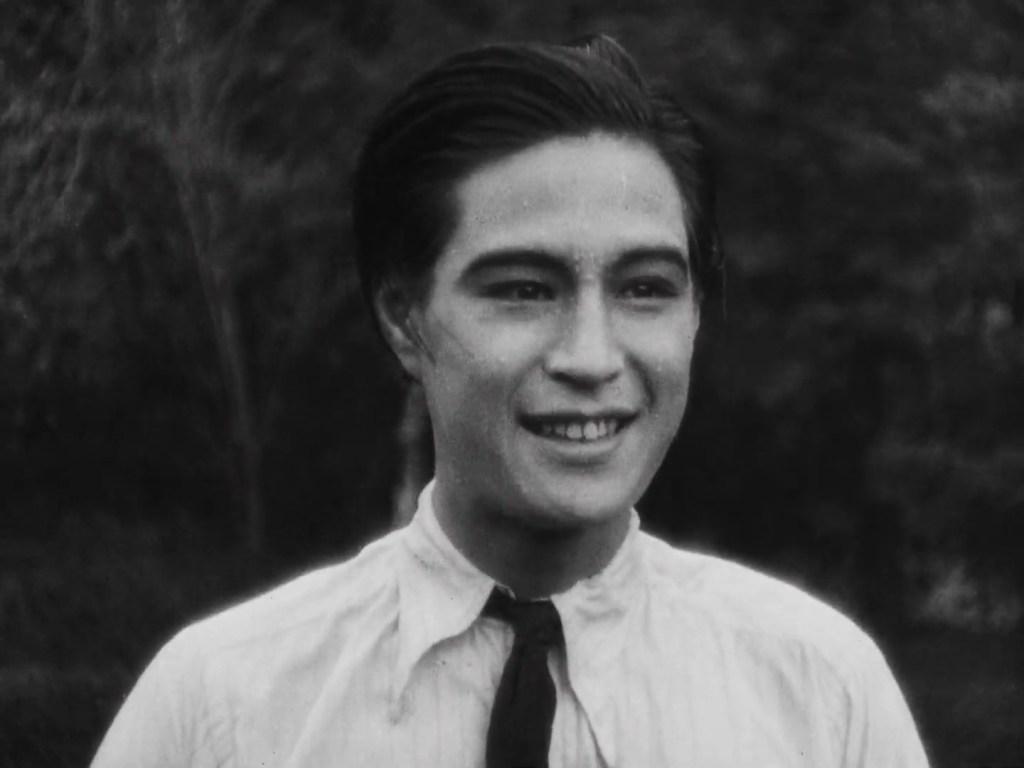

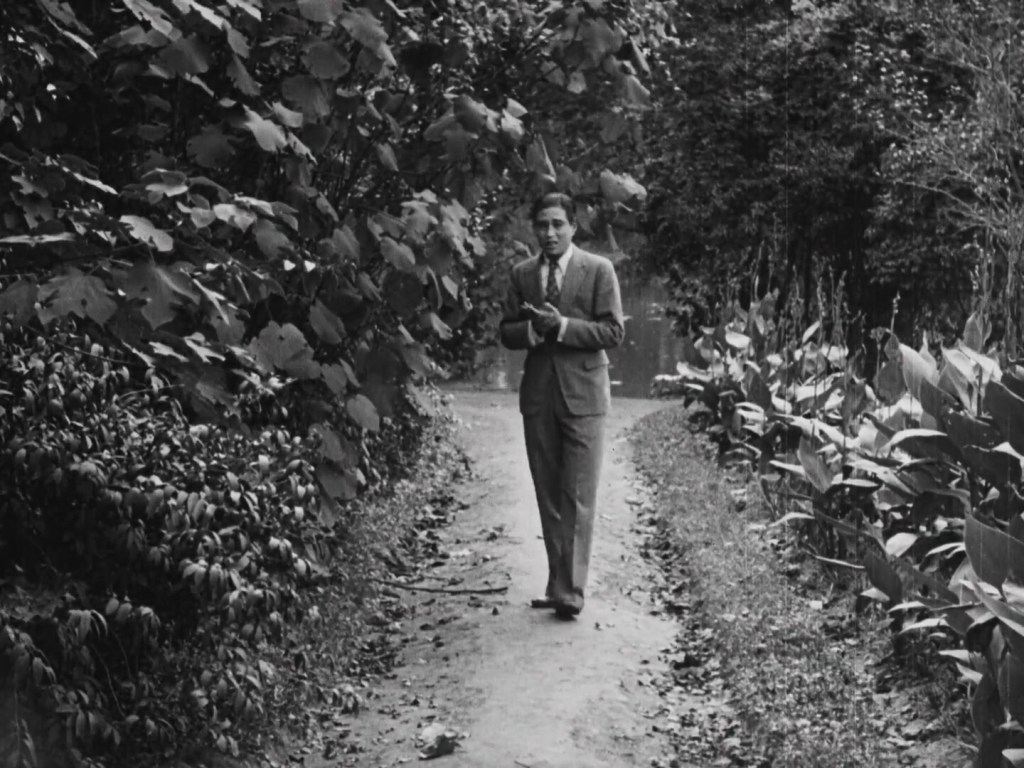

I was less enthralled by Jin Yan as Li Tsu Yi. His character is rather unsympathetic, and I wasn’t sure to what degree I was meant to feel sorry for him. His preference for Nei Fang without her children is delightfully foregrounded when, seeing mother and children walk away from their encounter by the pond, a dissolve shows us his subjective vision of her as the young girl he met – her children magically eliminated (quite literally dissolved away) from the frame. We are not invited to sympathize with him, I suspect, for this very reason. The narrative then (mis)treats him incredibly perfunctorily, killing him after one day’s copyediting ruins his health(!). The illness he has apparently carried secretly until now is never once suggested by Jin Yan’s performance, let alone by the film, earlier in the narrative. It certainly makes the moment shocking, but also (I think) less convincing. Jin Yan’s performance is animated, breezy. The character is not quite flippant but clearly gives too little thought to his actions.

Amid all this melodrama, I should also emphasize the touches of humour that save it from being overloaded with sentiment. The servant who betrays the lovers twice over is delightfully played. The character has no moustache to twirl, but the performer (whose name I cannot find in the cast list) gives it his all – squinting, chin-stroking, and scheming with evident relish. It was one example of the film moving (consciously or not) to a mode of parody. The fantasy sequence were Tsu Yi imagines fighting and killing Nei Fang’s husband is a delightful and direct evocation of Douglas Fairbanks, and Jin Yan gives a pleasingly free-spirited performance here. While I welcomed the eruption of something so unexpected on screen, I was again unsure quite how to take the tone of the film. The text of the book Tsu Yi reads that inspires this fantasy is parodically awful. The reading of trashy literature and subsequent fantasy might come straight from a Harold Lloyd film. By contrast, in another nice moment of doubling, Nei Fang’s fantasies later in the film are ones of fear. After Tsu Yi’s death, Nei Fang imagines the reactions of her family if she returned. These imagined scenes stand as a dramatic contrast to the fantastical scene imagined by Tsu Yi earlier in the film.

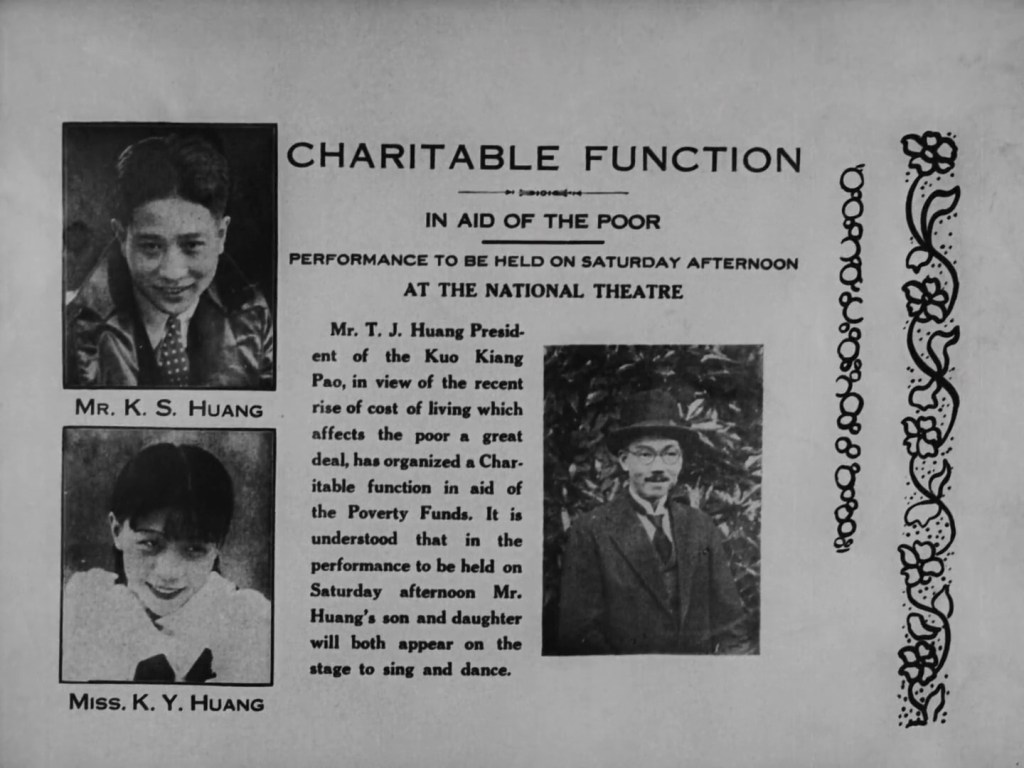

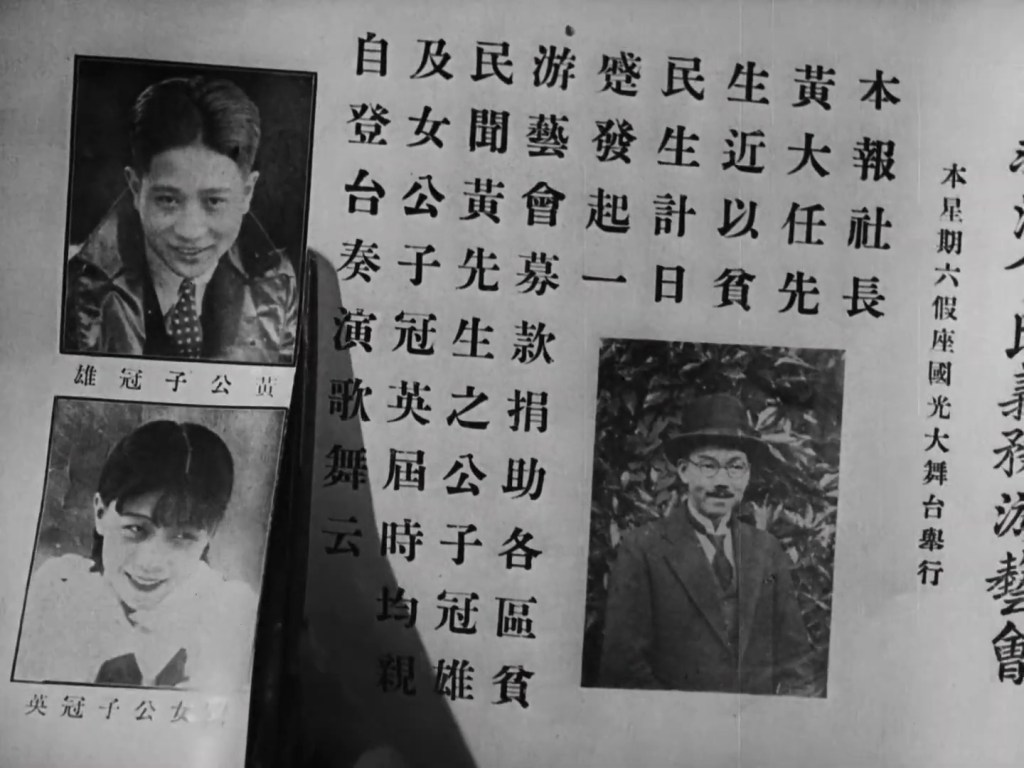

Related to this (imagined) presence of American film culture, I was also struck by the ways that Love and Duty looks out to western cultures. This is evident from the outset at the way even the film company’s logo of a flying plane suggests outward adventure, and how all the intertitles are original dual-language designs. There is also a contrast between the westernized clothing for the wealthier characters (marked out as such from their introduction) and the traditional clothing worn by the servant (and by Nei Fang herself when she is reduced to a humble trade in later life). The old Nei Fang also sees her children performing in an “international dance” on stage at a charity event – a curiously bland blend of western and music hall comedy. (Nei Fang is deeply moved, but I wasn’t sure how we are to take the contrast between her emotion and the apparent superficiality of the stage show she watches.)

However, more striking than these elements of fantasy or performance are the glimpses of reality the film offers. I was especially intrigued by the exterior scenes of contemporary China within and beyond Shanghai. The film offers the modern viewer, especially the modern western viewer, a glimpse of a lost past and a lost culture. (To state the obvious, much happened to China in the decade after Love and Duty was made.) The camera goes onto the streets and (especially) the backstreets to capture a splendid sense of outdoor space, to ground the drama in a recognizable reality. The quality of the image on the Blu-ray is excellent, and I found myself peering into the past with fascination.

Did all this add up to a satisfying viewing experience? While I certainly enjoyed Love and Duty, I confess that I found myself glazing over a little during parts of its long timeframe. The film is two-and-a-half hours long, and while this span allows space for the years of narrative on screen, it is still a long time to sit through in one go. I strongly suspect that this is the kind of film that is much more rewardingly encountered live with an audience. The pleasure of viewing it would no doubt be enhanced by the reactions of fellow spectators chuckling, gasping, and applauding. As it was, I watched Love and Duty alone in my living room. My television is no substitute for a large cinema screen, and the gentle fizz from my carbonated drink no match for the murmur of an audience.

I must conclude by returning to the context with which I began. Was my purchase of Love and Duty in such an expensive edition worthwhile? Well, I can treat myself to any number of excellent special features: videos, essays, restoration demos etc. I can learn about Maud Nelissen’s piano score, about how the film was rediscovered in Uruguay, and about how it fits into the wider culture of early Chinese cinema. Perhaps most impressive is the extensive essay on the restoration process. (No complaints about the lack of information on source material, lengths in metres, etc. with this release.) The whole package looks lovely. But I wish I had enjoyed the film itself a little more. I am left with a faint tinge of regret. Of course, it’s good to support any company that releases a silent film on Blu-ray, and I’m glad to have seen the film. But had I waited a few months, I could simply have watched this same restoration of the film on youtube. It might not stay there, and of course the visual quality is inferior, but if it isn’t a film I want to rewatch time and again then such a version might do. Part of my motivation for buying the Blu-ray in 2022 was the potential to show it on a big screen for students. As I explained earlier, the prospect of having students (or a departmental screening room) had vanished even by the time the Blu-ray arrived in the post. So I look at this glamorous box set again, and the regret creeps up on me. I paid more for this one film than I paid for the complete works of certain filmmakers on DVD. Was it worth it? Frankly, I’ve no idea.

Paul Cuff