Day 7 of Pordenone delivers us into the safe hands of Ufa for a film about the unsafe world of hyperinflation and theatrical exploitation…

Die Dame mit der Maske (1928; Ger.; Wilhelm Thiele). Alexander von Illagin is from a wealthy émigré family but now scrapes a living working for the Apollo theatre in Berlin – just as his friend, the Russian émigré Michail, works as a cab driver. Alexander meets Doris von Seefeld, the daughter of impoverished Baron von Seefeld, and advises her to try the theatre. Her father, meanwhile, owes money to the parvenu millionaire Otto Hanke, a timber merchant. Otto boasts to his girlfriend Kitty that Seefeld’s money will help him take over the Apollo, where Kitty works. Kitty’s lacklustre performance frustrates the theatre director, who immediately casts Doris in her place. Doris objects to the risqué costume she must wear. As a compromise, she becomes the anonymous “Lady with the Mask”. Doris pretends to her father than she has sold the rights to his memoirs and lies about the nature of her new employment. But “The Lady with the Mask” is an instant sensation, and Otto is enraptured. Meanwhile, Alexander discovers that his family had hidden jewels in his boot before they fled to Germany. However, he gave his boots to Michail, who in turn exchanged them at a broker… Doris and Alexander admit their feelings for one another, but Otto prepares to reveal Doris’s identity if she doesn’t submit to him. The baron discovers that Doris has been deceiving him, and follows her to the Apollo, where he realizes his daughter’s sacrifice. After escaping the clutches of Otto, Doris finds her father with Alexander, who has recovered the boot and his fortune – and the couple are reunited. ENDE. [As revealed in the post-film restoration notes, the original German version had a much more complex ending. There, Otto is reconciled with Kitty, and Doris and Alexander reunite via a more complex series of events – just as the recovery of the boot is woven more thoroughly into the denouement. The export version that survives clearly contains not just different editing and/or titles, but different footage shot expressly for it.]

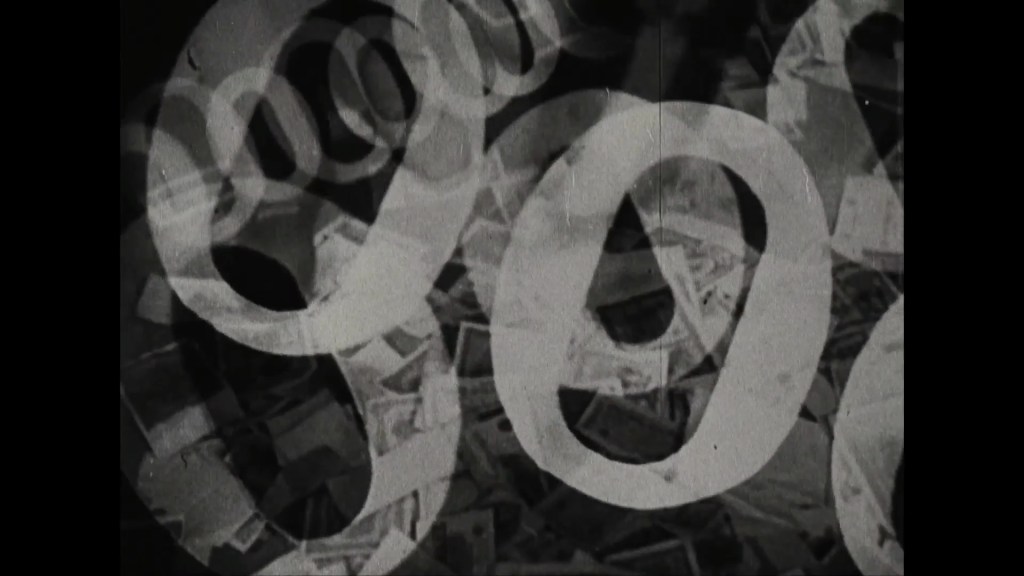

What a wonderful treat! This is a visually rich and dramatically engaging production. The lighting and camerawork are superb, evident from the fabulous “inflation” montage that opens the film. Here, multiple superimpositions, overlaid text, slow motion, rapid cutting, and complex movements and dissolves take us dizzily through time and space. Though it is setting the context for the film, and providing us with information about time/place, it is more than anything a way of plunging us into the unstable world of contemporary Germany. The mad flurry of images is confusing, disturbing, bewildering. We cannot find our feet, just as the characters have had their world pulled from under them. These are characters who grew up in the pre-war world of stable, not to say repressive, imperial orders. Alexander is from an unnamed eastern land, perhaps Russia – as his name and friendship with Michail suggests – or perhaps just a former part of Austria-Hungary. Doris’s family likewise sports an aristocratic ”von”, and father writes memoirs of hunting in Africa, suggesting an old Prussian family with colonial connections.

Though the film signals these various intriguing contexts, Die Dame mit der Maske is ultimately quite a light treatment of poverty and hardship. The opening titles announces the story as one of the “silent tragedies” of hyperinflation, but even if it is more a drama than a comedy, I certainly wouldn’t call it a “tragedy”. Nothing tragic happens, and the characters might be struggling but they all end the film with money – and some kind of restoration of the meaning of their various aristocratic titles. Michail is the only really lower-class character, and he cheerfully acts as a kind of servant to Alexander. He is the comic sidekick whose adventures with his newly-bought taxi and his efforts to find the fortune-bearing boot serve as light relief to the drama. In general, though, the upper-class characters (Doris, Alexander, Seefeld) are well-mannered and sympathetic, while the lower-class ones (Otto, Kitty) are brash and occasionally violent. Otto’s pursuit of Doris attempt to bridge the class barrier, but the film concludes by each couple (Alexander/Doris, Otto/Kitty) re-established within their own class. In the end (at least, as far as the original German version is concerned), all the characters end up affluent and emotionally reconciled. No-one dies, and I’m not sure anyone has learned any lessons, either.

The cast perhaps reflects the overall tone and thrust of the film. French actress Arlette Marchal is believable and sympathetic as Doris, though one never has a real feeling of emotional depth to the character. Marchal ably signals the self-sacrifice and wounded pride of Doris as she performs in her scanty costume, but the film doesn’t ask her to do more than this. A more complex drama (or a different performer) might suggest a sense of liberation or exploration through her stage performance, i.e. the allure of stardom. But Doris wants nothing more than to support her father and (presumably) live an old-fashioned domestic life. The film might exploit her body and show off her allure, but it is neither so cruel as to expose her (literally and figuratively) to true degradation – nor to use her stage persona to explore her sexuality. Indeed, the relationship between Doris and Alexander doesn’t have a strong sexual dimension.

As Alexander, the Ukraine-born Wladimir Gaidarow is very charming, but the drama goes not provide his character with real complexity to explore or express more emotional depth. Though we get fleeting references to his former life, the film (at least in this surviving export version) does not give any glimpse of what he might have done to survive, or what kind of person he or his family were before they came to Germany. Did he fight in the war, or in the Russian civil war? There is absolutely no sense of trauma here, nor any emotional baggage from his past. The only thing tangible from his former life is his title and the jewels cached in his boot. Again, a more interesting or daring film would have at least suggested some complexity of Alexander’s past.

The most interesting female character in Die Dame mit der Maske is surely Kitty. But though I love seeing Dita Parlo march around being spiky and pouty and self-confident (all while wearing an extraordinary set of Weimar hotpants and bra), I couldn’t say she embodies a particularly complex character. She makes Kitty into an entirely believable figure – ambitious but unskilled, jealous and proud. But the film doesn’t give her the chance for any more than this. Though we might guess that her past was tough, even tragic, to have attached herself to the loutish Otto (and saved herself from far worse), the film gives not the slightest hint of backstory.

For me, Heinrich George is the best thing in this film. Every time I see his name on the credits, I perk up. He never disappoints. In Die Dame mit der Maske, he’s that wonderful combination of the spoiled child and the violent adult. He’s both pathetic and dangerous, pitiable and contemptible. The way he lurches from self-pity to fury, from depression to aggression, is brilliant. Every time he appears on screen, you know the scene might change at any second. He might deliver a laugh, or make you gasp in fear. He is brilliant as the parvenu millionaire, smarmily puffing his cigar or smothered in foam in his bath, raging and thrashing in petulant fury. His round, shining cheeks are babyish – but his sheer bulk has real menace. When he seems about to force himself on Doris in the penultimate sequence, you really believe he has the will and the callousness to assault her. But when he relents and lets her go, you realize that he’s more complex than this – that there is some kind of conscience at work. Otto is not, quite, a monster. It’s a really great performance by George.

I must conclude by saying, once again, how enjoyable Die Dame mit der Maske was to watch. It isn’t a masterpiece of any depth, but it is a fascinating – if somewhat superficial – portrayal of this period of German history. I wish that it had more to say about the context and characters it mobilizes, and I wish it mobilized them to more interesting ends – but I was never frustrated while watching the film. For this presentation, the piano music by Günter Buchwald was first rate, though I’d be curious (as ever) to know what the original orchestral score was like in 1928. (Unlike many such productions of this period, I cannot find the name of the arranger/composer responsible for the music at the premiere.) It’s a great shame that only the export version of Die Dame mit der Maske survives, but it’s great that the restoration credits so openly explain this, and suggest how the original German version was different. Far too many digital versions of silent films gloss over or deliberately obscure this complex issue. So my compliments to the FWMS for being so transparent and informative. A highly enjoyable and interesting film to watch.

Paul Cuff