I often find myself searching on the FIAF database for the location of archive film prints. The database isn’t definitive, but it is often a helpful indicator. Anyone searching for archive copies of Abel Gance films would likely have spotted an entry for Le nègre blanc (1912). Click further and you would have seen that the Filmmuseum Düsseldorf was listed as holding a 16mm print of this film. I think I’ve known, vaguely, of this FIAF listing for many years. It had never occurred to me to investigate it further. Why? Well, I supposed that something so rare would have long since been checked and confirmed by another researcher. I also suspected that the copy might be so fragile that it was unavailable for viewing. The fact that the recent Gance retrospective at the Cinémathèque française did not include this film in its “complete” screening schedule seemed to confirm this (see my four posts from September 2024). But the question remained, lodged in my brain.

In the last few years, I have felt more willing and able to venture onto the continent in order to pursue various strands of my research. With a prospective trip to Germany planned for December 2025, I decided in advance that I should investigate this mysterious print in Düsseldorf. Over the autumn, there followed a long exchange of emails with various archivists, and the team at Düsseldorf kindly agreed to check their print in advance of my visit. I received the startling information that they had two prints of this title: one on 16mm and another, shorter, copy on 9.5mm. The former was approximately the length one would expect for an early two-reel film; the latter was clearly an abbreviated version of a single reel. My curiosity grew (as did my doubts), but I knew I must hold my excitement until someone had checked the prints to confirm their identity. Before I reach the inevitable (and I’m sure not surprising) conclusion of this search, I should say why the very idea of this film’s existence is so interesting. Interesting to me, anyway…

For a start, this print of Le nègre blanc would be the earliest surviving film directed by Gance. Some of his earlier appearances as an actor are preserved in films by others, but La Folie de Docteur Tube (1915) is his earliest known work as a director to exist. That this is so is something of a miracle, as the film was never commercially released. It is also frustrating, since all of Gance’s two- or three-reel films that did get released in 1912-15 are considered lost. These are the films that earned him enough success to make the more substantial features of 1916-18, films which anticipate so much of the dramatic and aesthetic qualities of his masterpieces of the next decade. What was Gance like as a filmmaker before 1916? We simply don’t know. So to find a print of any Gance film from 1912 would be of enormous interest.

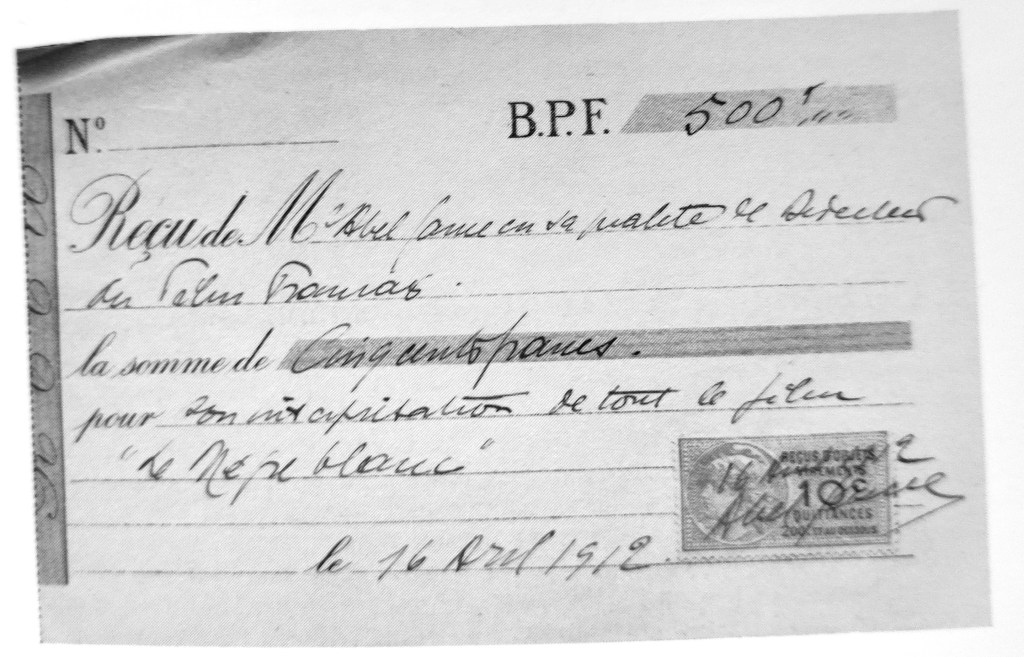

Secondly, Le nègre blanc is of interest for its subject and stars. The earliest synopsis I have to hand is in Sophie Daria’s Abel Gance, hier et demain (1959), which was based on a number of conversations with Gance. As a result, it is often inaccurate and evasive – but certain details are found nowhere else. The book offers a brief sketch of Le nègre blanc, adding that “it was never projected” (44). Having searched the major film journals and major newspapers of the period, I can indeed find no evidence of a public screening. But that the film was actually made is indicated by the survival of a document from 16 April 1912, citing payment for Gance’s performance from Le Film français, the company which produced Le nègre blanc. (They paid him 500F. You can see below an image of this document, taken from the auction catalogue of 1993, at which Nelly Kaplan sold her huge collection of Gance’s personal papers. Happily, the highest bidders were two French state archives.) And before you ask, yes, Gance did play the lead role of the titular black character, so presumably would appear on screen in blackface. To what end? Well, a little more information on Le nègre blanc is given in Roger Icart’s biography of Gance from 1983:

A black boy goes to school with white children. Cold-shouldered and ridiculed by his classmates, he decides to make himself look like them by painting his face and body white. His appearance thus disguised provokes a redoubled dose of mockery, while he dies, his body slowly poisoned by his naive stratagem. (49)

As I discovered when I searched for the phrase, “le nègre blanc” (which I hope you don’t need me to translate) had a remarkably wide circulation in the early twentieth century. It appeared in any number of cultural and political contexts, as a derogatory term, a term of entreaty, of warning, of classification. In using it for the title of his film, Gance was clearly tapping into a phrase that was common enough on people’s lips. Sophie Daria cites the film as “anti-racist”, while Roger Icart cites it as “anti-racist(?)”. I like the hesitancy of Icart’s parenthetical question mark. Clearly, the film can be read both as a parable about the poison of racism – but might also hint at something less palatable about the insurmountable nature of race. Added to these murky cultural waters is the fact that, in the 1930s, Gance was identified by some as Jewish and vilified as such. (The right-wing press in France mounted numerous vile attacks on his films and him. The label “Jew”, for them, could be applied to anyone they didn’t like. Chaplin, too, was called a “Jew” by like-minded fascists in this period.) That Gance was adopted seemed to hint at family secrets, and the figure of a fatherless male seeking to rebuild (or adopt) a family is a recurrent theme throughout his films. However crude, Le nègre blanc is surely an important marker of this interest in lone men seeking identity and belonging – a kind of destiny – and being destroyed by it.

But Gance was not the first to use this title for a film. Le nègre blanc was the title of one of the numerous “Rigadin” comedies starring Charles Prince, this one being produced by Pathé in 1910 (some sources say 1912). This film (viewable online) follows much the same plot as Gance’s, though its comedy is less touched by tragedy. In the Pathé version, a black man is mocked at a high society party when he proposes to a white woman. Rejected because of his colour, he finds a potion to turn himself white. In this form, he returns to the woman – but she is now engaged to another man. In revenge, he slips her some of his potion and she turns black. Rejected by her fiancé because of her colour, she tries to seek solace with Rigadin. But now he has the last laugh and rejects her because she is “black” and he is “white”. Like Gance’s synopsis, the Pathé film is an awkward satire on the idea of race – and (in its casting and use of blackface) a perpetuation of racial stereotypes. Perhaps the very existence of this contemporary film discouraged Gance’s producers from releasing his version.

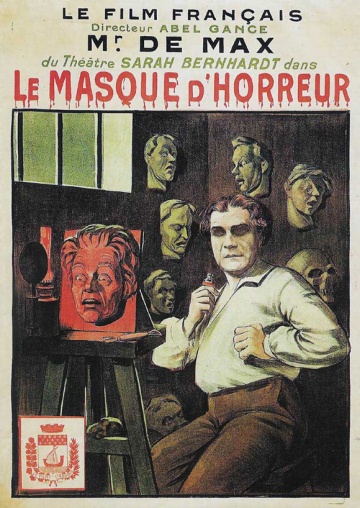

Whatever the reason, the theme of Le nègre blanc reappeared in one of the few Gance films of this period about which we have a fuller description: Le masque d’horreur (1912), starring Édouard de Max. In this film, an artist has spent years trying to create a lifelike mask expressing the greatest fear imaginable. Driven almost to the point of madness, he decides at last to become his own model. He sits before a mirror, takes poison and cuts his wrist. (As the artist smears his blood over the lamp that lights his face, so Gance tinted his film red to mimic the gruesome aesthetic.) As the artist dies, so the mask becomes more and more lifelike. He embraces his creation, and dies. Like Le nègre blanc, therefore, Le masque d’horreur portrayed a figure seeking self-transformation through the creation of a mask – and the adoption of this mask caused his death. Unlike Le nègre blanc, however, Le masque d’horreur was actually shown. After a processing error botched the first print struck of the film, it was seemingly reprinted and projected in May 1912. This brief foray into the public realm did not stop the film’s disappearance. Like everything else from this period of Gance’s directorial work, it remains lost.

Returning to Le nègre blanc, another major interest is the fact that it was made in the year Gance married his co-star in this film, Mathilde Thizeau. About Thizeau, I know frustratingly little. Though she was his first wife and starred in at least two of Gance’s films in 1912, she is a virtual non-entity in most accounts of the filmmaker. Sophie Daria cites the existence of this woman in a carelessly off-hand way: “the young cineaste had married a journalist older than himself: Mathilde, a good and simple girl with whom he lived in harmony for a few years” (65). Ouch. Given that Daria certainly got her information from Gance himself, this is quite an insult. (Of course, by 1959 he was married to Sylvie (née Marie Odette Vérité), his third wife.) The truth is that Mathilde Thizeau was only five months older than “the young cineaste”: they were both 23 when they married in 1912. Furthermore, Gance’s biographer Roger Icart offers a far fairer (though no less brief) account of Mathilde as “a young journalist of great spirituality, like [Gance] enamoured by art and philosophy, who would participate in all his endeavours and inspire him to write numerous poems, dedicated ‘to my Thilde’. Above all, she would reinforce his ambitions as an author” (23).

But who was Mathilde Thizeau? Where did she come from? What was her background? Who were her family? All I know is drawn from the scant evidence of her name in some contemporary journals. Thus on 28 October 1912, the Journal des débats announces the marriage of Abel Gance, “dramatist”, to Mathilde Thizeau, “journalist”. I am re-reading Proust at the moment, and today reached the last part of Swann’s Way (1913), in which the narrator recalls his childhood love for Gilberte. They often play together on the Champs-Élysées, and while the narrator waits in hope of Gilberte’s arrival, he makes friends with an old woman who comes loyally to sit on a bench. Here, she passes the time – come rain or shine – by reading what she calls “my old débats”. To this scene, set one imagines sometime in the early 1880s, an old woman expresses her fondness for her old journal. Proust’s novel was first published the year after the announcement of Gance’s marriage. What a strange world this is, and how charmingly old-fashioned, even then, to announce one’s marriage in the Journal des débats.

Searching for anything written by Thizeau, I eventually found my way to the issue of Le Gaulois du Dimanche published on 31 August 1912, two months before her marriage. There – among the pretty pictures, the silly adverts, the coverage of Massenet’s death and the latest crisis in the Balkans, the photos of cats and dogs, the latest women’s fashions, and a sentimental song – is Mathilde Thizeau’s piece: “La Rose qui a vu jouer ‘Héliogabale’”. A curious title, and it took me a little while to identity the “Héliogabale” it cites. It seems that Héliogabale (the Roman emperor Elagabalus) was the subject of a small number of artistic works in France around the turn of the century – there were a few plays, plus Louis Feuillade’s film Héliogabale (1911). Thizeau quotes a line from act I, scene ix of her particular source: “…et les plafonds ouverts / Sur eux laissent tomber les roses une à une…” (“…and over them the open ceilings / Let fall the roses one by one…”). I eventually found these enigmatic lines in the libretto of Déodat de Séverac’s eponymous opera of 1910. I knew Séverac by his lovely piano music, as well as by his charming opera Le Cœur du moulin (1908). He was from Languedoc in southern France and portrayed the landscapes and people of this region in his music, so it’s no surprise to learn that Héliogabale was first performed in Béziers. This took place in August 1910 in a huge arena populated by 15,000 spectators. Despite its place in a festival in high summer, the opera was a financial disaster and swiftly disappeared. But it was revived for a small number of performances at the Salle Gaveau in Paris in February and April 1911. It was here, one presumes, that Mathilde Thizeau experienced it.

Thizeau’s short prose poem takes inspiration from the scene in which Héliogabale arranges that his enemies, whom he has invited to dine, be smothered by thousands of rosebuds and petals emptied from the rafters. In Thizeau’s text, a rose watches the performance of this scene in the opera as the blossoms smother the banqueters below. She marvels at what she imagines to be the revenge of the roses against the men who have cut them from their stalks. At night, she decides to take her own revenge on the beetle which seeks to steal the nectar from her heart. When the beetle finally crawls into the flower, she “bleeds” herself to death: emptying her nectar into a delicious pool that the beetle drinks until it is insensible. Then the rose lets herself die, her petals falling over the beetle and entombing it in blossom. Thus ends the only piece of writing I have ever read by Mathilde Thizeau. What to make of it? Well, it’s very fin-de-siècle, and the imagery of male predator entombed inside a female flower is very… well, familiar. But it’s charming for how particular it is, and the fact that the story is taken from the perspective of a flower is curious. It’s a sidelong glance at a tiny corner of the world of 1912, and it’s an animistic close-up of nature.

I suppose it interests and charms me because it makes me want to know more. Did Thizeau see this opera with Gance? What was his reaction? And did they write together? Gance was performing in the theatre as well as being involved in the cinema. In the 1910s, he appeared in some important productions of D’Annunzio’s exotic, multimedia French plays – including Le Martyre de saint Sébastien (1911) and La Pisanelle ou La Mort Parfumée (1913). The latter ends with the protagonist being suffocated while inhaling the heady scent of roses, so not so far away from the world of Héliogabale. (And I have written about the links between D’Annunzio and Gance elsewhere.) So here we have this newly married couple, thinking and living theatre and music, within touching distance of the heady world of late romantic art. Such a world must have seemed far in advance of some of the films they were able to make in 1912-13, and Gance abandoned cinema for a year or more in 1913-14 in order to complete his own epic, multimedia stage drama La Victoire de Samothrace. How much of Mathilde lies in this piece, and what kind of life did they lead in these years? Sometime in 1914, Gance met Ida Danis, a secretary working for his new production company, Le Film d’Art. He fell in love with her and divorced Mathilde in 1919. Of course, Ida died in 1921 during the production of La Roue, leaving the filmmaker with a lifelong sense of loss. (Never having married Ida, he married her sister Marguerite in 1922. The marriage ended in turmoil in 1930, by which point Gance had met Sylvie…)

All of which is to say that Gance’s choice of film over theatre was echoed in his choice of Ida over Mathilde. Film history knows all about Ida as Gance’s “great love”, which only makes Mathilde’s fate the more poignant to me. Here are the limits of history. I know when Mathilde was born and died, and when she married and divorced Gance. But I don’t know her: her interests, her ambitions, what animated her soul, what drew her to Gance, or how they fell in love. I don’t even know what Mathilde looked like. Perhaps there is a photo somewhere in the archives, but when I did my research in Paris many years ago, I didn’t think to inquire. She died in 1966, but of her life after her divorce from Gance I know nothing. Did she know or care what happened to him – or see his films? Did he know or care what happened to her? And what did she do with her life?

For all these reasons, therefore, I was keen to know if the Filmmuseum Düsseldorf did indeed hold one or even two prints of Le nègre blanc. Eventually, the prints were located and examined. I received my answer… As I’m sure you’ve guessed, neither print was of Gance’s 1912 film. Instead, they were reduced versions of a film by the same name from 1925. This was made by Serge Nadejdine, Nicolas Rimsky, and Henry Wulschleger for Films Albatros. (I told you that title had surprising circulation in the early twentieth century.) At some point in the past, decades ago perhaps, the wrong iteration of this particular title was selected and recorded on a database. So no lost oddity for me, and no lost oddity for you.

But this wild goose chase offers another valuable lesson in the problems of film history. Evidently, we rely on a lot of unverifiable data. Scholars (including myself) copy and paste much of our information on a film’s cast, crew, length, date etc. without being able to check it against primary sources. (I discussed this same issue in my frustrated search for Der Evangelimann (1923).) And many films like Le nègre blanc do not survive for us to test our information or assumptions. But my experience chasing after a false entry on the FIAF database demonstrates that it’s always worth asking archives directly about what they possess. Material from this period is often sketchily catalogued on archival databases, let alone centralized platforms like FIAF. And the archivists themselves are a necessary and inspiring set of guides through the unique material they hold. If I did not get to see Le nègre blanc, I’m sure there are plenty of other surprises out there, waiting to be discovered.

Paul Cuff

My thanks to Andreas Thein and Thomas Ochs of the Filmmuseum Düsseldorf, and to Oliver Hanley for oiling the wheels of communication.

References

Sophie Daria, Abel Gance, hier et demain (Paris: La Palatine, 1959).

Roger Icart, Abel Gance, ou Le Prométhée foudroyé (Lausanne: l’Age d’homme, 1983).

Fascinating adventure and research as always! Did you get to visit and watch anything at Filmmuseum Düsseldorf?

LikeLike

Thank you! Sadly, I never got to go to Germany in December. By the time I received confirmation about the Düsseldorf film(s), the price of travel had gone up too much to justify the trip I was hoping to make to Germany. This is why I never made it to Mainz to see the film concert of EIN WALZERTRAUM, per my post in December. Still, better not to have gone all that way to be disappointed within the first few seconds of watching the wrong version of LE NEGRE BLANC. Hopefully I will find a reason to go to the Filmmuseum Düsseldorf one day in the future…

LikeLike