This week, the second part of my exploration of the life and work of Ilya Ehrenburg. Though my excuse for writing this is Ehrenburg’s connections with the films and filmmakers of the 1920s-30s, I am also interested in the memoirs as a work of reflection on this period. As I recorded in my last piece, they offer an amazing glimpse of the interwar world – and of what that world meant in retrospect.

Part 2: Later years

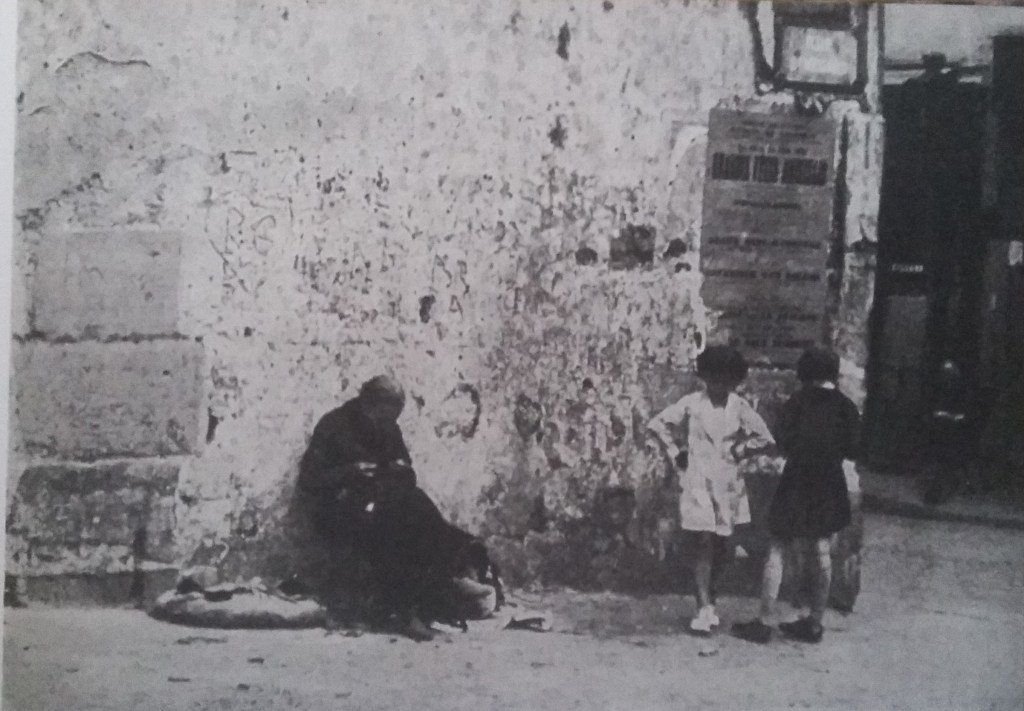

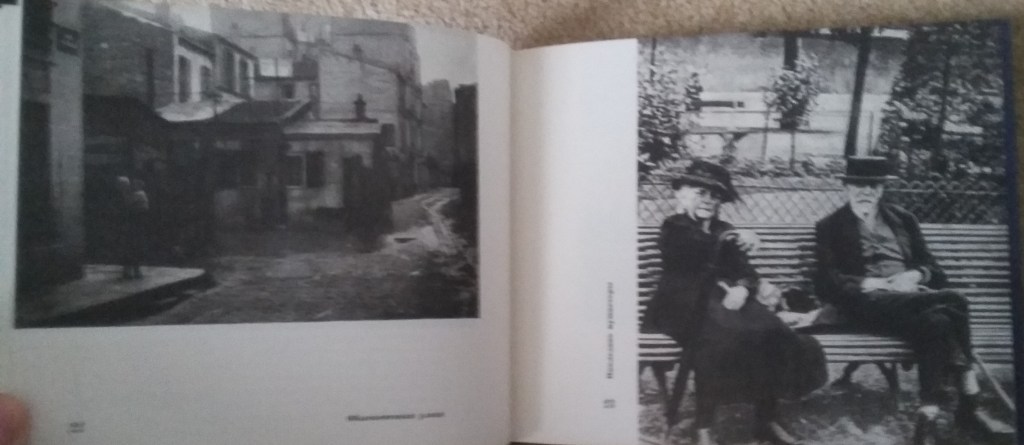

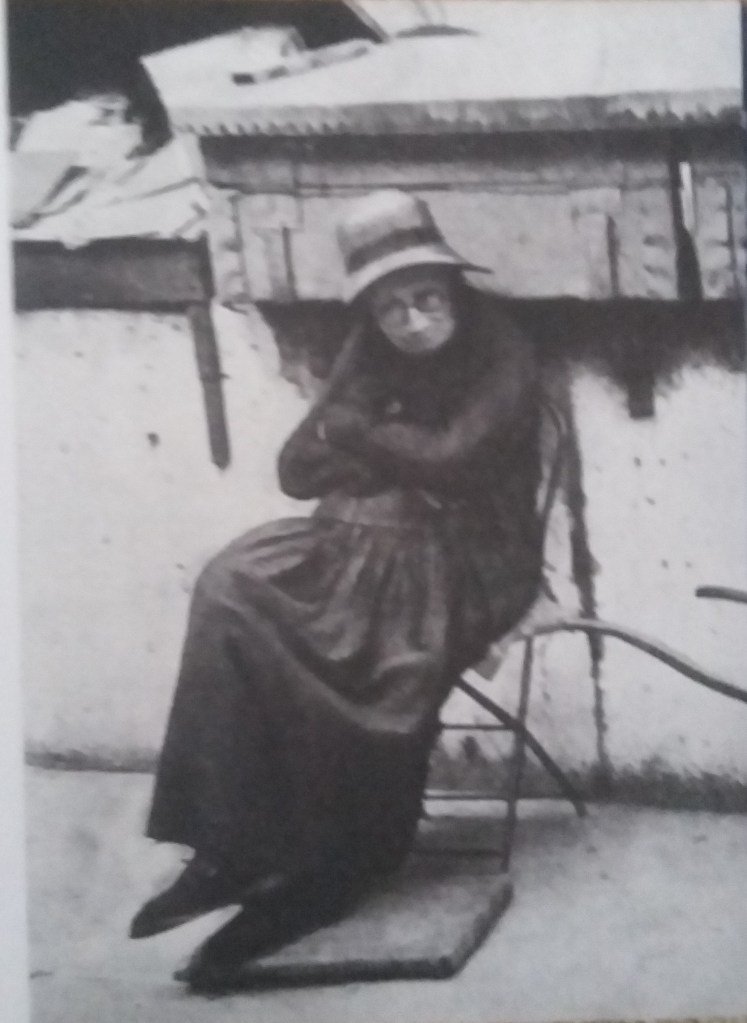

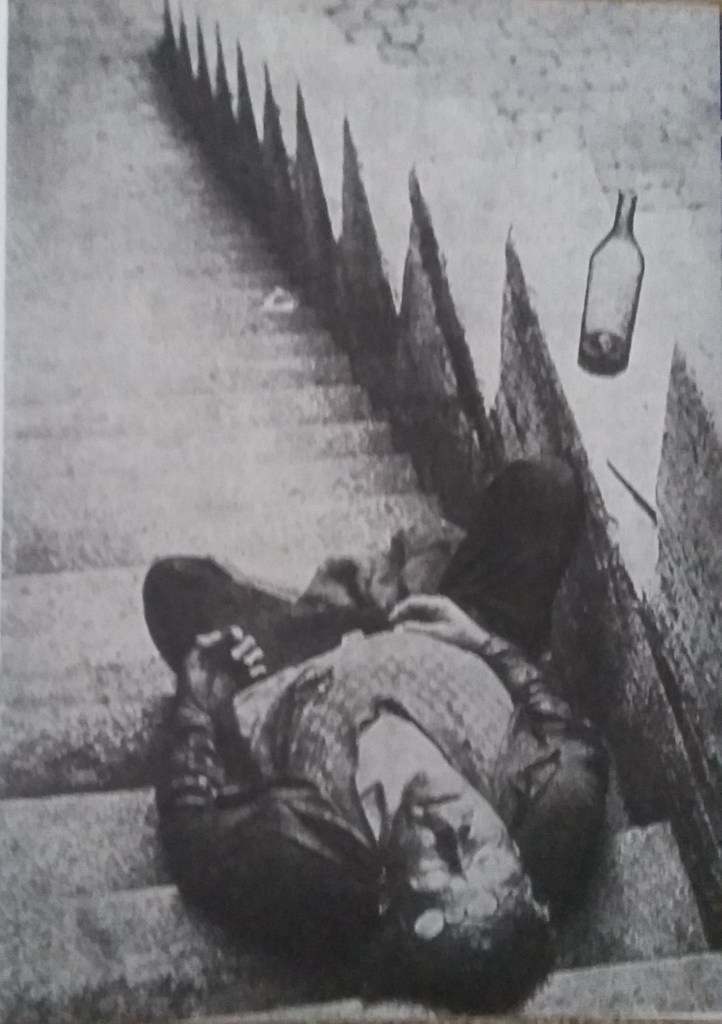

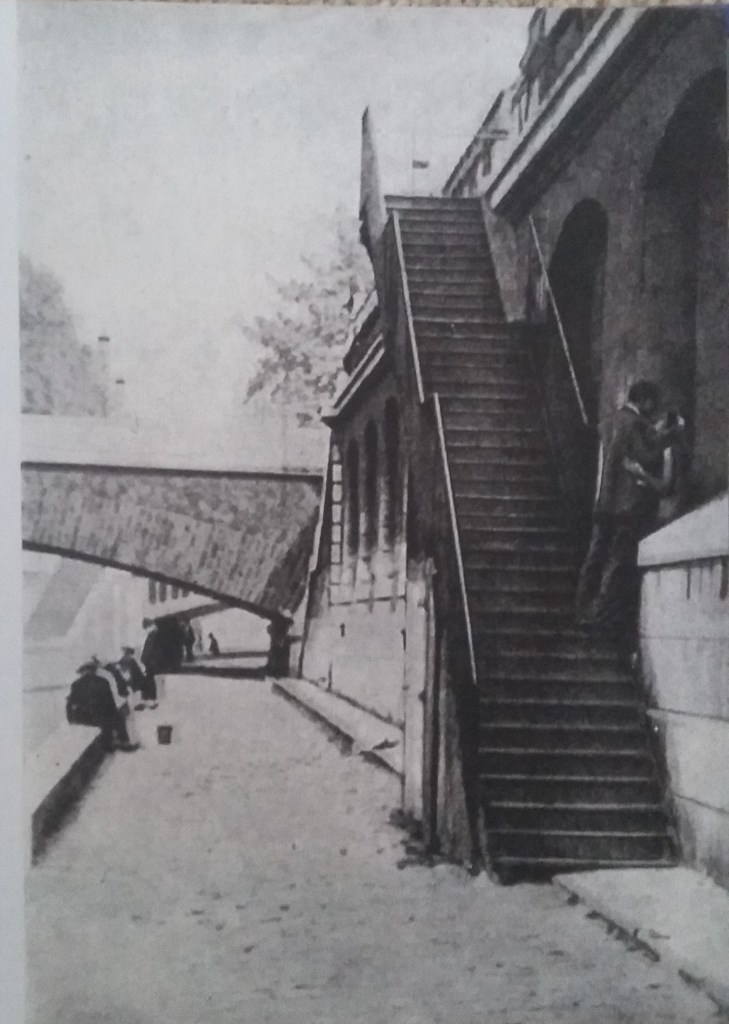

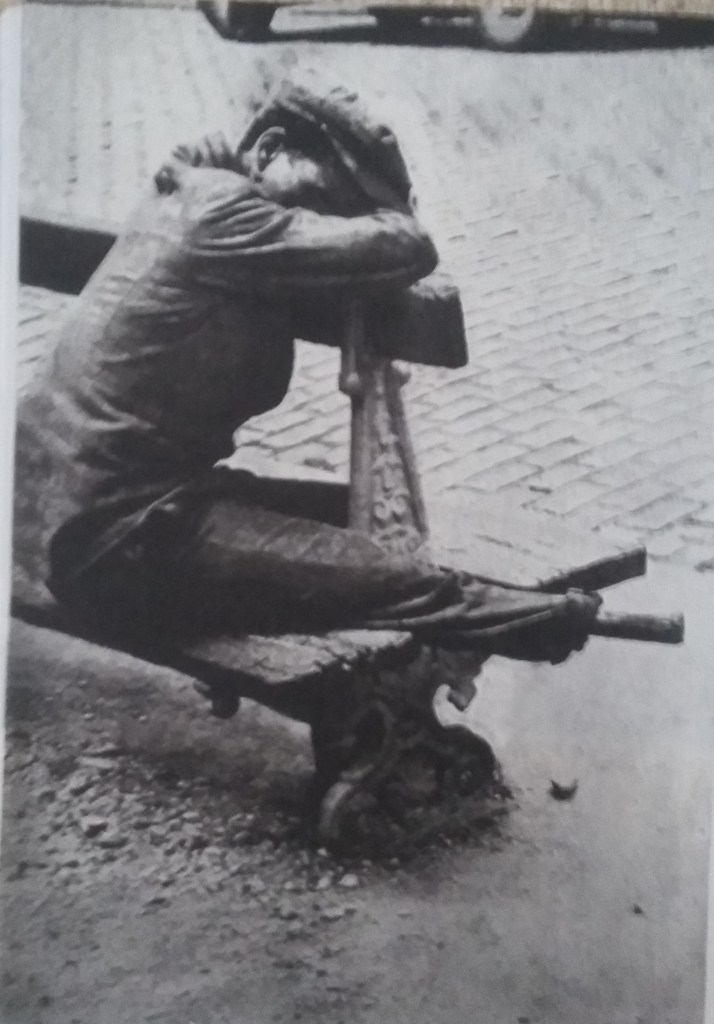

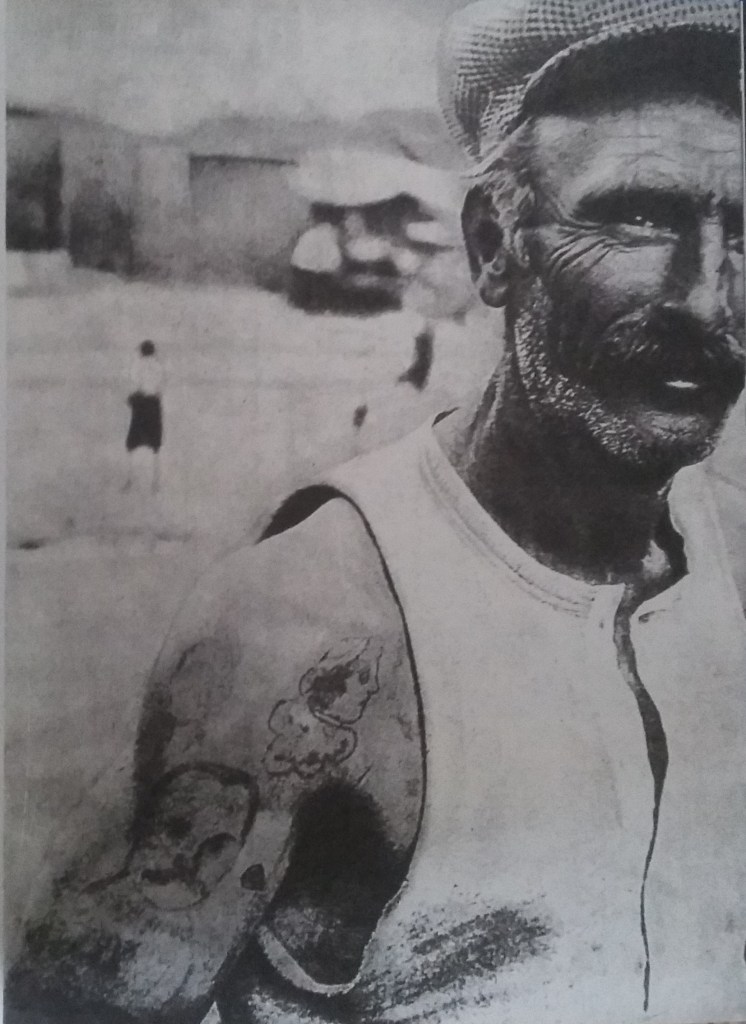

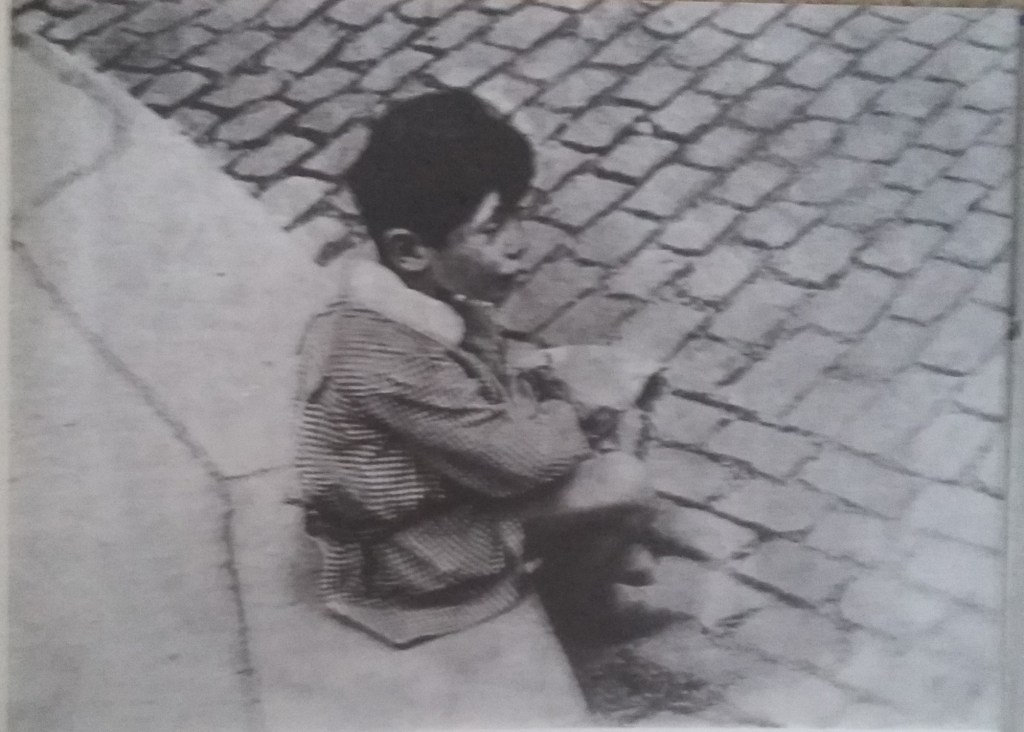

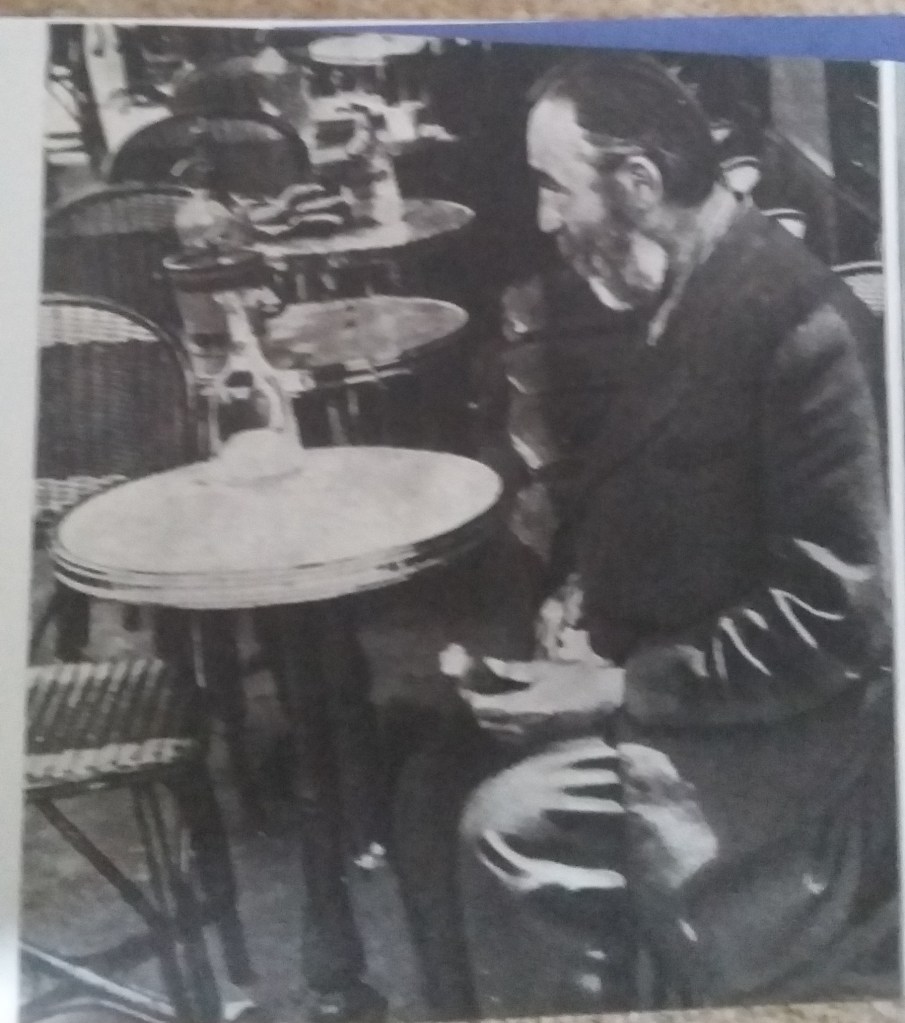

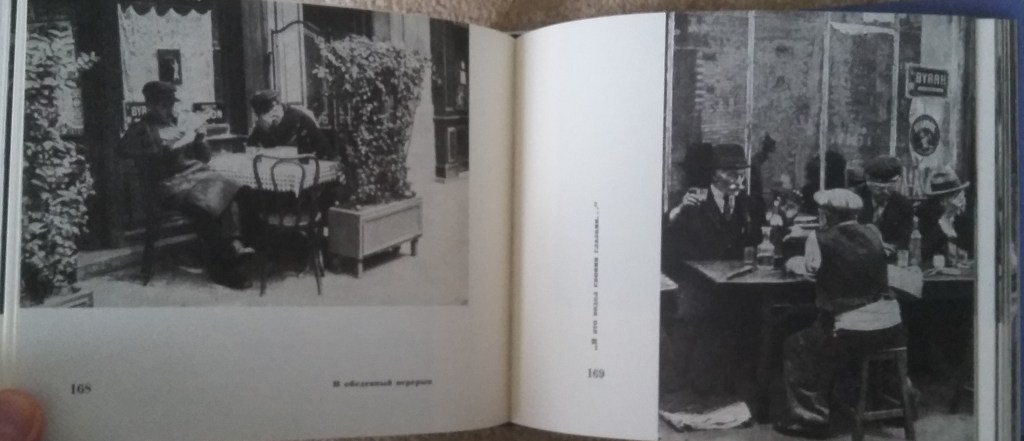

As a kind of coda to the Paris of the 1920s, I want to start by mentioning Moi Parizh (My Paris), a book that Ehrenburg published in 1933. It is a photo album-cum-essay, a visual and literary walk through Paris, the city that Ehrenburg loved so much. But this visual and textual exploration is far from touristic. Ehrenburg is interested not in the facades of great buildings, or even in the great and the good who inhabit them. He is interested in those who sleep rough, in those who survive in the poorest neighbourhoods, in those who live lives that go otherwise unrecorded in history. Ehrenburg knew poverty firsthand, and his snapshot (sometimes covert) images of Paris reveal not just the subjects of his camera but the knack of the observer who knows where to look. These images are often uncomfortably intimate in their portrayal of homelessness and destitution. But they are not exploitative, and there is a kind of tenderness in the way Ehrenburg seeks out the corners of the city to find life – young and old, active and inactive, abled and disabled – going about its business, or doing nothing at all. My Paris is as beautiful as Dmitri Kirsanoff’s Ménilmontant (1926), one of my favourite films, where the street scenes attain a poetry founded in reality. Whereas Kirsanoff tells his story purely through images (with no intertitles), Ehrenburg offers a parallel text commentary on his photographs. Here is a representative passage on the Seine:

It all begins on the steps, where the unfortunate ones sleep. They sleep on stone as on a bed of feathers. They also sleep on the riverbank. They’re particularly keen on wandering under the bridges. It’s cool there in the summer and there’s shelter from the rain. Shadows mill in the gloom. Some like the Pont d’Auteil, others – Pont Alexandre III. Neither eyes nor rags can be clearly distinguished. Life is defined by sounds: a loud dog-like yawn, curses, groans, grunts and the sinister hoarseness that suggests the nearing of the end. The bridges of Paris – old bridges and new bridges, with the thundering metro, with moustachioed Zouaves – join the two banks: the Bourse and the Académie, the markets and the Sorbonne. They have different names. Trains clatter over some, dreamers stroll on others. From below they are all alike; they are shelter and quiet. Beneath them live those who no longer have the strength to cross from one bank to another. […]

The stairways to the Seine are not just a certain number of steps: they are light-headedness and fate. Down leads poverty, and down leads love. Anyone who has loved in Paris knows the damp fog that rises over the Seine, the sorrowful cries of a little steamer and the quivering of the shadows. Lovers kiss, pressing each other against the handrails or sliding down; they, too, wander beneath the arches of the bridges. No one is surprised – love, everyone knows, is homeless.

The Seine also has other admirers. These don’t try out the steps. They pause on the bridge, then plummet like stones. Who’s to say why they preferred the cold of the water to gas or the rope? Some are hurled down by hunger, others by grievances, others by love. […] As for the Seine, it’s not to blame for anything: a river like any other. It’s a gate as well. A gate left open. People sometimes leave through it. Then hooks crawl along the sandy bed. The dreamers, meanwhile, keep strolling up and down the embankments. (My Paris, 7-8)

Reading My Paris, you can understand why Pabst’s production of Die Liebe der Jeanne Ney did not satisfy Ehrenburg. The contemporary reality from which he wanted art to emerge is more potent in his text and images than in Pabst’s drama. It is not just that Die Liebe der Jeanne Ney did not contain the reality of Ehrenburg’s fiction, it is that the film did not contain his experience of contemporary life. The author does not record if he knew or saw Ménilmontant (perhaps it was among the films he brought to Russia in 1926, cited last week), but one senses that aspects of it would surely have appealed.

In Ehrenburg’s memoirs, the streets of Paris take on a more personal meaning in retrospect. In the late 1950s/early 1960s, the act of recalling scenes from these spaces is clearly as moving for Ehrenburg as it might be for us to see his images of My Paris another half-century later. “When I come to Paris now I feel inexpressibly sad – the city is the same, it is I who have changed; it is painful for me to walk along the familiar streets: they are the streets of my youth” (I, 66). The retrospect of the memoirs – and the way this perspective inflects its record of the past – noticeably sharpens later volumes. Like other great works of recollection, this book is as much about the act of memory as memory itself. As I have written on this blog many times, the distance between ourselves and the past is one of the major reasons that the world of silent cinema is so potent. One senses from the silent images of My Paris a world that is both incredibly tangible and irrevocably absent.

This sense of distance opens out in the later volumes of Ehrenburg’s memoirs. After 1930, the idealism that motivates so much of the art and artists he recalls is whelmed in political realities. This shift can be felt in his references to cinema. Increasingly, politics redefines – and prescribes – the boundaries of art. Ehrenburg talks about meeting Lewis Milestone, another Russian Jewish exile, who regales him with anecdotes about filming All Quiet on the Western Front (1930): “[Milestone] told me that during the shooting the producer Carl Laemmle came to him and said: ‘I want the film to have a happy ending’. ‘All right,’ Milestone replied, ‘I’ll give it a happy ending: Germany shall win the war’” (III, 127). This rather pointed comic story is followed by a grimmer conclusion. Ehrenburg recounts being present for the exhibition of All Quiet in Berlin in 1931, when Nazi agitators release a hundred mice into the cinema in protest at the film’s anti-militarism (III, 201). Political pressure within Hollywood likewise forestalls Milestone from adapting one of Ehrenburg’s novels in 1933 (IV, 9-10). The times are changing.

Ehrenburg travels through Austria, Czechoslovakia, and Romania. By the time he returns to Moscow in 1935, his homeland is in the grip of an increasingly paranoid and controlling Stalin. Creative freedom in the arts is being squeezed. Ehrenburg has a fleeting encounter with filmmaker Alexander Dovzhenko, who has just been summoned by Stalin. This ominous summons is now the norm. Stalin’s “suggestions” to artists are euphemistic instructions, to be obeyed on pain of disfavour, arrest, or death. Under these conditions, expression and innovation are stifled. As Ehrenburg puts it: “If a writer or an artist does not see more than the numerical ‘mass’, does not try to tell people something new, as yet unknown to them, then he is hardly any use to anyone” (IV, 98).

The Spanish Civil War begins. Ehrenburg leaves Russia for Spain. Art is a solace, a comfort, sometimes a distraction. Besieged in Madrid, he watches Chaplin films (IV, 145). But the knowledge of the future haunts Ehrenburg’s pages. He knows their cause is doomed, just as he knows the fate of his friends and comrades. These are volunteers from Russia and the east, men like him who have led extraordinary lives in pursuit of their beliefs. “Of all these men, I was the only one to survive. [One] was killed by an enemy shell. As for the others, they were destroyed for no reason at all by their own people” (IV, 176). It’s a devastating line, the fulfilment of the threats already being made to artists like Dovzhenko.

When Ehrenburg returns once more to Moscow in December 1937, the “great purge” is underway. His daughter tells him about countless arrests, disappearances, executions. Conversations between them must be conducted in whispers for fear of reprisal. Ehrenburg’s homeland is now an alien, threatening place. “I was totally bewildered; I felt lost, no, that is not the word – crushed” (IV, 190). It is with a strange sense of relief that he returns to war-torn Spain. But the Republican cause is near its end. In January 1939, Ehrenburg is one of the thousands of refugees fleeing across the Pyrenees into France. During the retreat, his party must abandon or destroy their baggage. Ehrenburg finds himself forced to burn his own books (IV, 231). It is an image with chilling resonance.

He returns to Paris, where he remains when the Second World War begins. During this period of the Nazi-Soviet pact, Ehrenburg finds himself a neutral, if anxious witness. He is in Paris when the Germans enter. He recalls more voluntary destruction of equipment, of documents. So much polluted smoke enters the sky that the rain turns black. “This, too, had to be lived through”, he observes (IV, 260-1) – and the brevity of his words make the depth of his recollected emotion stronger. Ehrenburg leaves the city he loves above all others. His nation not yet at war, he finds himself travelling back to Russia via Berlin. A Jewish Communist, Ehrenburg negotiates his way through Hitler’s capital city feeling “like a live fox in a fur shop” (IV, 266-7).

The fifth volume of his memoirs, called simply “The War”, is also the shortest. This is despite Ehrenburg being in a state of ceaseless activity, travelling among the Russian forces and writing accounts of all aspects of the war in the east. As I wrote in the preamble to my previous post, Ehrenburg also collected eyewitness accounts of atrocities committed by the Germans and their allies. In his memoirs, one senses the exhaustion of these years, and that much of what he saw or heard was beyond description. Often, he records details in passing that resonate more than a longer description could. He recalls once holding in his hand a bar of soap made from the rendered flesh of murdered Jews (V, 30). It’s an image, an idea, so grotesque that Ehrenburg need not say more. He admits later: “I find that to explain all I have seen and lived through is beyond my powers” (VI, 107). If Ehrenburg is sometimes reticent to speak of himself directly, or at great length, he offers a glimpse into his mindset of these war years. Again, he describes himself as a kind of romantic who is forced to reorient himself by the world around him:

By nature as well as upbringing I was a man of the nineteenth century, more given to discussion than to arms. Hatred did not come to me easily. Hatred is not a particularly creditable emotion and is nothing to be proud of. But we were living in an epoch when ordinary young men, often with agreeable faces, with sentimental feelings and photographs of the girls they loved, had, in the belief that they were the elect, begun to destroy the non-elect, and only genuine and profound hatred could put an end to the triumph of Fascism. I repeat, this was not easy. I often felt pity, and perhaps I hate Fascism most bitterly because it taught me to hate not only the vile inhuman idea but also its adherents. (IV, 267)

I have read only fragments of Ehrenburg’s wartime journalism, and his memoirs are reluctant to quote much of his own work save occasional poems. This wartime material, written to appeal and inspire the Red Army in its fight, has a quasi-infamous reputation for its propagandistic rhetoric and invocations of violence. On this, I simply haven’t read enough to comment – and it’s rather beyond the scope of this piece to do so. All I can say is that the memoirs offer a painful and moving retrospective of the man he was. One senses that the older Ehrenburg resents not what his younger self did or wrote but why he had to act as he did and write what he did. As in the passage cited above, hatred did not come naturally to him – but come to him it did.

Having written about this enforced hatred of the war years, Ehrenburg’s post-war work – as witness, as journalist, as cultural ambassador, as promoter of peace – is even more striking for its empathy. His encounters of those who survived the war and its genocides are among the most affecting in the memoirs. In one extraordinary passage, Ehrenburg meets a Russian girl from Kursk who loved a German soldier during the war. Knowing Ehrenburg’s propagandistic vilification of German manhood, the girl tries to explain how she could fall in love with the “enemy”. To do so, she tells him that her feelings were like those of Jeanne Ney. Ehrenburg in turn reaches for film to try to explain his own feelings. Unable to pity this girl in the immediate context of the war, years later he recalls seeing Hiroshima mon amour (1959). Seeing the heroine’s affair with a German solider, and her subsequent mistreatment by her vengeful community, Ehrenburg finally comes to understand the life of the woman from Kursk (V, 98). Even as an artist, one might understand the world better only through the art of another.

Again and again, Ehrenburg returns to the idea of art as a universal requirement for human communication. Having been absent from much of his daughter’s life, it is only decades later when he reads her novel that he understands her childhood (IV, 59). As ever, this desperately moving personal admission is swiftly passed over in favour of encounters with others outside his family. In one such, Ehrenburg is approached after the war by a young woman who had survived the siege of Leningrad. She gives him her diary to read, and Ehrenburg is astonished at how often the woman wrote about what she was reading:

When the girl came to fetch her diary, I asked her: “How did you manage to read at night? After all, there was no light”. “Of course there wasn’t. You see, at night I remembered the books I’d read before the war. This helped me to fight against death”. I know few words that have affected me more deeply; many a time I have quoted them abroad when trying to explain what enabled us to hold out. Those words bear witness not only to the power of art, they are also a pointer to the character of our society. (VI, 13)

Ehrenburg continues to travel, viewing the material destruction of the places he knew – and the first efforts of reconstruction. Revisiting Kiev, he sees the house where he was born in rubble. Then he visits the ruins of the enemy. In Nuremburg, he attends the trial of Nazi war criminals. In one of the most extraordinary passages in the memoirs, Ehrenburg is sitting in the gallery when suddenly he sees Hermann Goering looking up at him. He realizes that Goering recognizes him as the infamous Jewish Bolshevik that Goebbels attacked personally in the Nazi press. Suddenly all the other men in the dock are looking at him. Cinema makes an uncanny appearance in this scene, too. The Nazis in the dock are shown footage from the concentration camps. Ehrenburg watches their faces, and records seeing Hans Frank, the Governor-General of occupied Poland, weeping (VI, 34-5).

But there is little catharsis. As Ehrenburg writes, the events of the war years were not a singular instance of barbarity but a symptom of broader attitudes that did not die out in 1945: “The attempt has been made to present fascism as a stranger who accidentally intruded on decent civilized countries; but fascism had generous uncles, loving aunts, who to this day enjoy good health” (III, 207). After 1945, he continues travelling, writing, organizing. He visits the USA for the first time. Here, he observes the segregation of black Americans. At one function, Ehrenburg grows thirsty and invites an architect to whom he is talking to a bar to get a drink of water. The architect makes excuses and leaves. Someone explains that the architect would not be allowed into the bar, which is for whites only. “I found myself lacerated by someone else’s humiliation”, Ehrenburg writes. “I no longer wanted to drink nor, to be quite candid, did I want to live” (VI, 63-7). On another occasion, a woman tells him how a white man demanded that she – a “half-caste” woman – be thrown off a whites-only bus. The conductor placated the angry white by pretending that the woman had dark hair because she was “a Jewess”. The woman relaying this story to Ehrenburg explains how terrifying she found the experience. “It was then for the first time that I felt ashamed of being a Jew”, writes Ehrenburg; “I wished I were a black Jew” (VI, 69).

Proselytizing for peace as he travels across the new and old worlds, Ehrenburg returns to Russia to find another wave of purges underway. Among countless others, figures from the Jewish resistance to Nazi occupation now find themselves on Stalin’s blacklist. Ehrenburg’s friends sleep with a revolver on their bedside table in case there is knock at the door in the night. The gun is not for the intruders, but for themselves (VI, 277). Everyone, including Ehrenburg, called Stalin “The Boss”. This term was not used from familiarity but from fear. “In the same way Jews in the past never pronounced the name of God”, Ehrenburg writes. “They could not really have loved Jehovah: he was not only omnipotent but pitiless and unjust” (VI, 302). Ehrenburg was glad to have lived long enough “to know the cruel truth” about Stalin and that “millions of innocent people had perished” on his orders (V, 45-6).

But this did not lessen his faith in socialism, nor his desire to name and confront social injustices. And I must conclude this (already rather long) piece on a more positive note. Put simply, Men, Years – Life is an astonishingly rich and rewarding account of the first half of the twentieth century. But more than the events or people it covers, I was moved by Ehrenburg’s generosity of spirit – and moved by his optimism, in spite of the events he experienced, for new ways of human co-operation. As his post-war reflections (in particular) acknowledge, it is through experiencing other cultures that we understand one another and realize our commonality. For this reason, the imposition of borders and boundaries is both counterfactual and counterproductive:

Culture cannot be divided into zones, like cutting a cake into slices. To speak of western European culture as separate from the Russian, or of Russian culture as separate from the western European is, to put it plainly, a sign of ignorance. […] Only dwarfs use stilts, and the people who shout about their national superiority are those who are not quite sure of themselves. (VI, 109)

As with culture, so with wider relations between peoples. “Solidarity with the persecuted is the first principle of humanitarianism”, he writes (VI, 127). Here, too, cinema becomes part of Ehrenburg’s hope for younger generations. He cites his love for Vittorio De Sica’s Ladri di biciclette (1948) and meets many of the new Italian directors who would define the coming decades (VI, 175-7). New ways of seeing, and new ways of exploring human experience, offer new avenues for mutual comprehension.

For all the horror and misery Ehrenburg witnessed across his life, his memoirs conclude with a message of hope for the future. It is also, one senses, a hope that he feels is necessary to maintain, regardless of circumstances. As he himself admits, there is a strain of romanticism in Ehrenburg that I find deeply sympathetic. He has faith in art and in the people who strive to produce it, to engage with it, to learn from it. It is faith not only in the value of art as aesthetic creativity, but as a way for societies to understand the spiritual needs of human beings. “I believe that without beauty to satisfy the spirit no social changes, no scientific discoveries will give mankind true happiness. The argument that in art both form and content are dictated by society, however true, seems to me too formal” (VI, 338). Having lived through dictatorships, censorships, genocides, Ehrenburg recognizes that art represents a kind of freedom that is beyond classification – or control. The very act of writing his memoirs is itself, surely, a mode of release, of escape. It is also an act of hope. “Who knows, perhaps something remains of every one of us? Perhaps that is what art is”, he writes (IV, 151). Art might only be a “something” of ourselves, but through it we can reach out to one another – across culture, and across time. By the end of the sixth and final volume, this is exactly how I felt about Ehrenburg – a voice, and a person, reaching out to me.

Paul Cuff

References

Ilya Ehrenburg, Men, Years – Life, trans. Tatania Shebunina and Yvonne Kapp, 6 vols (London: MacGibbon & Kee, 1961-66).

Ilya Ehrenburg, My Paris, trans. Oliver Ready (Göttingen: Steidl, 2005).