This second part of my conversation with Oliver Hanley covers his work as a curator at the film festivals in Bonn and Bologna.

Paul Cuff: Since 2021, you’ve worked alongside Eva Hielscher as co-curator of the Stummfilmtage Bonn. How did you get involved with this festival?

Oliver Hanley: I had a good connection to the festival already. I had attended every year since 2008, and had even brought films to the festival during my time at the Austrian Film Museum in Vienna. So, I was familiar with the programming at Bonn, and when Eva and I took over the curatorship, we tried – and still try – to follow the tradition of our predecessor, Stefan Drößler, whose curatorial work we admired very much. But of course, we also try to bring something new and to show films that would not have been shown previously.

PC: And when did you become involved with Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna?

OH: It was already after I became co-curator of the festival in Bonn. In late 2022, I got the offer to curate the “One Hundred Years Ago” strand at Bologna. I was a bit anxious at first at the thought of taking it on, especially being already involved in the Bonn festival at this point, but it seemed like a once in a lifetime opportunity, so I thought: just go for it!

PC: Is doing these two festivals, both taking place during the summer, difficult?

OH: It can be strenuous doing both. There’s about a six-week gap between them, so the preparation for one runs parallel to the other. But in a way, the work is complementary. When I watch films for my Bologna research, I come across films that I think could work in Bonn. Or I take films to Bologna that were shown in Bonn because I know they will work there as well. Besides, I know that my experience at Bonn and Bologna is very privileged. It might be a lot of work, but at the end of the day, I’m programming for two festivals that are approximately a week or ten days long. There are people curating film programmes for film archive cinematheques throughout the entire year! They have to create three shows a day, every day, maybe with a summer break. I can understand that you can’t devote the same amount of care and attention to detail with those programmes that I can when working for the two festivals.

PC: I presume Bonn and Bologna have distinct identifies and aims. Do you need to bear this in mind when curating the material being shown?

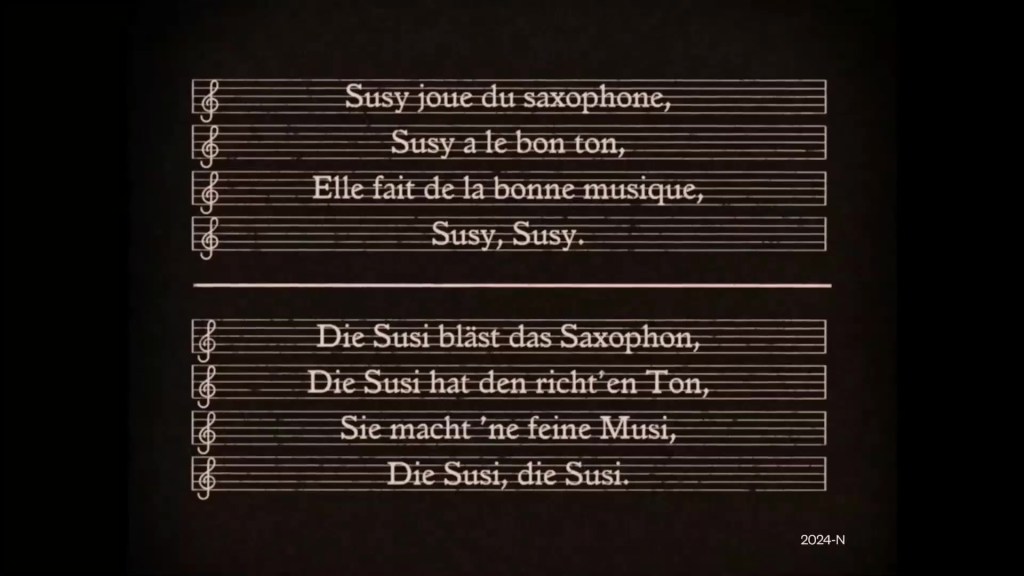

OH: Yes. While the festivals have some similarities, they also have their differences and this in turn affects the programming. Bologna, I feel, is very much a festival for cinephiles and specialists, while Bonn is aimed at a much wider and predominantly local public. Bonn is free, it’s all outdoors, and anyone who comes knows it has this forty-year tradition. People will come and watch all the films, but in some cases, these might be the only silent film screenings they attend across the year. In others, you have the obsessive silent film fans from the region who come over to see what they can. At Bonn, we try to go against the grain a little, which has always been the ethos of the festival – but ultimately it must appeal to a wider public. In Bologna, however, I can show things that I would never show in Bonn. For the “One Hundred Years Ago” strand, I need to show newsreel footage for the historical context. At Bonn we sometimes show documentary feature films, but newsreels are very difficult to accommodate. The same goes for things like fragments or incomplete films. The makeup of Bologna, and the existing form of the strand I curate, allows me to incorporate this kind of material more easily. But I essentially apply the same kind of the same curatorial approach to both Bonn and Bologna. You can’t just randomly throw stuff together: you need to have a clear reason for your selections. The films need to work in a kind of dialogue with each other.

PC: Do you always hope to provide clear through-lines across a festival?

OH: This year, more than in previous years, I think it was very obvious in the Bonn programme. Sometimes we made exceptions where we couldn’t really find a connection between the two films we wanted to show each evening and combined them according to other, more pragmatic criteria like running time. But in my Bologna programme the thematic connections between the individual films in the individual screening slots were very evident as well this year.

PC: What kind of programmes work best?

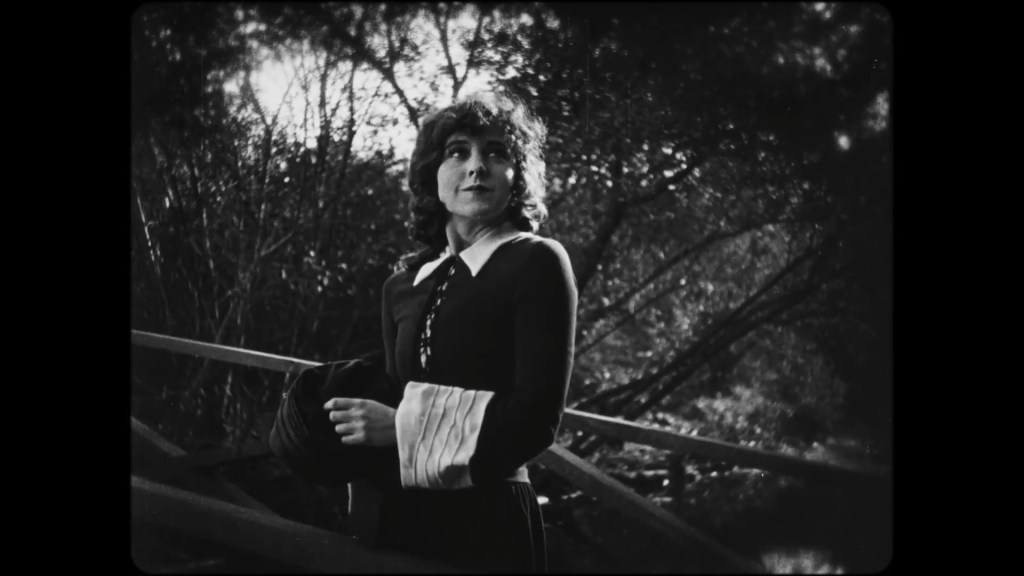

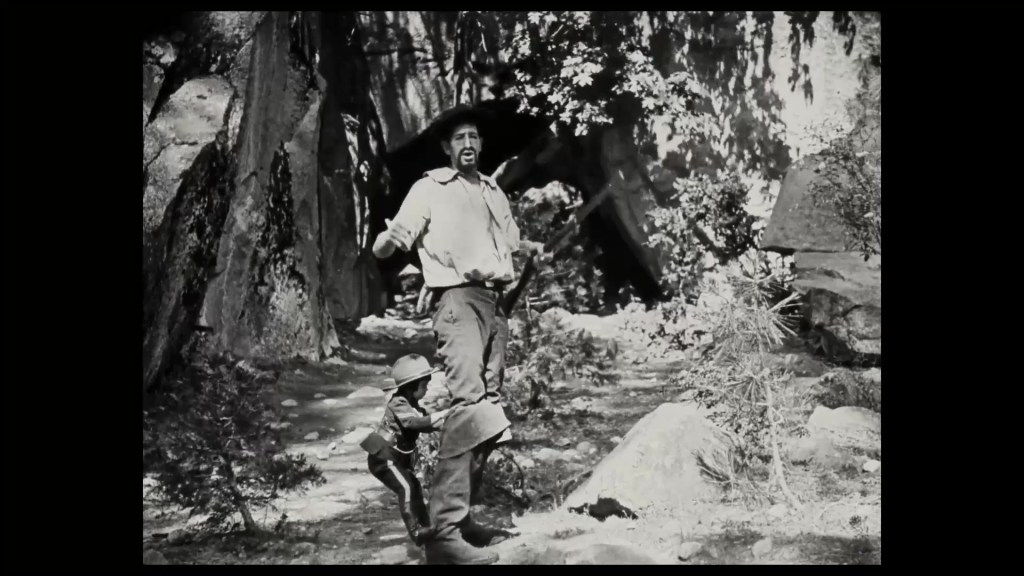

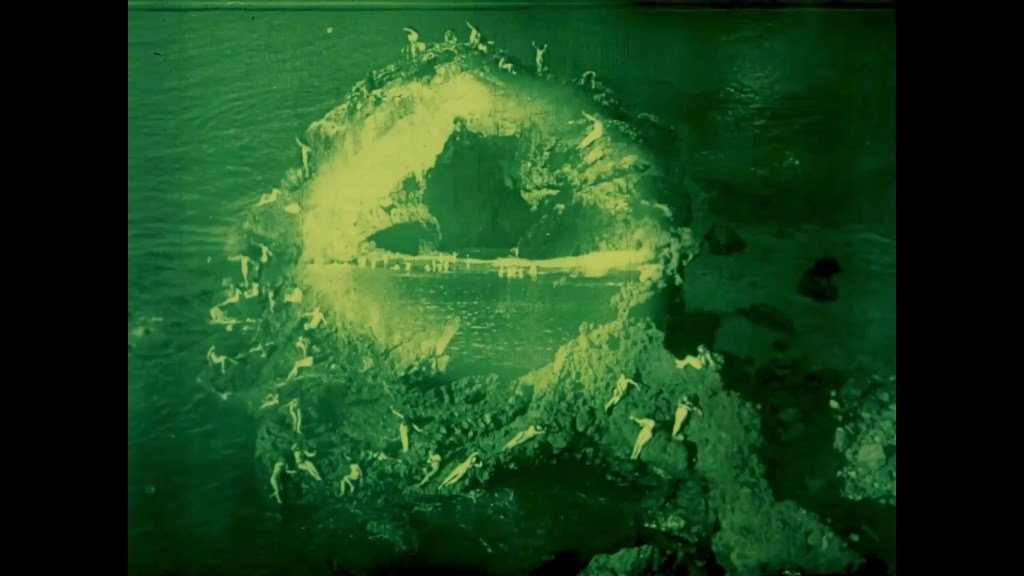

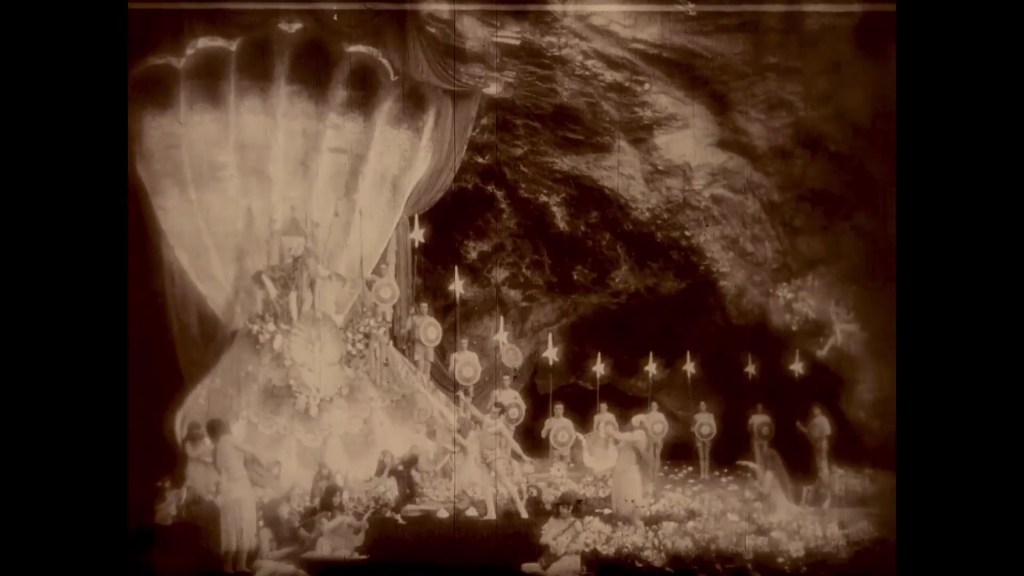

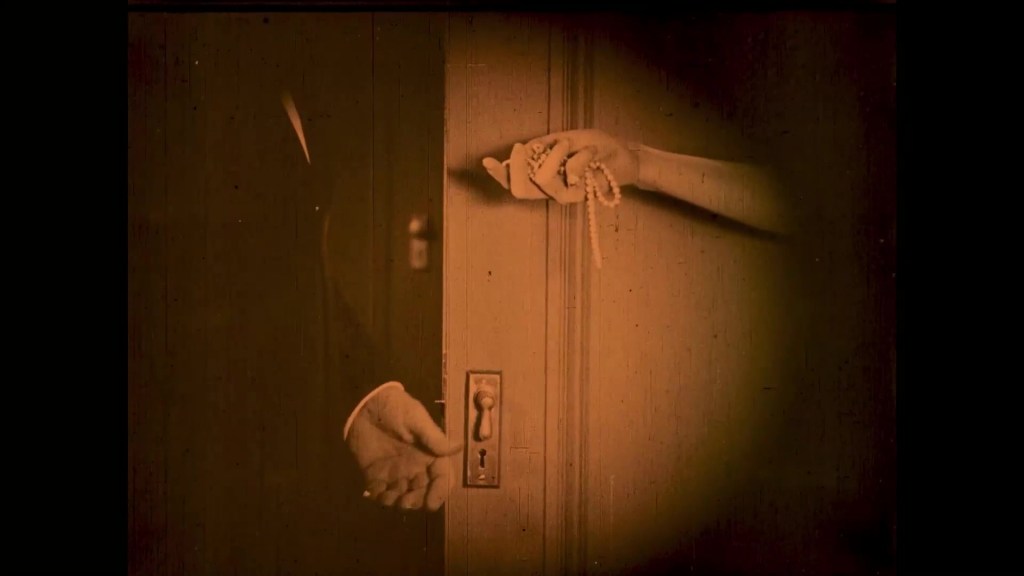

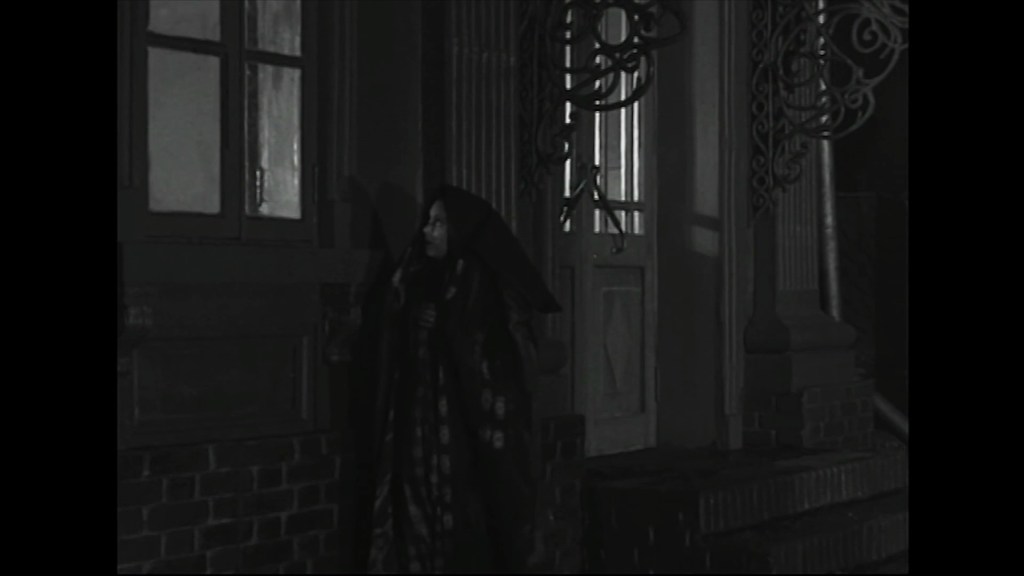

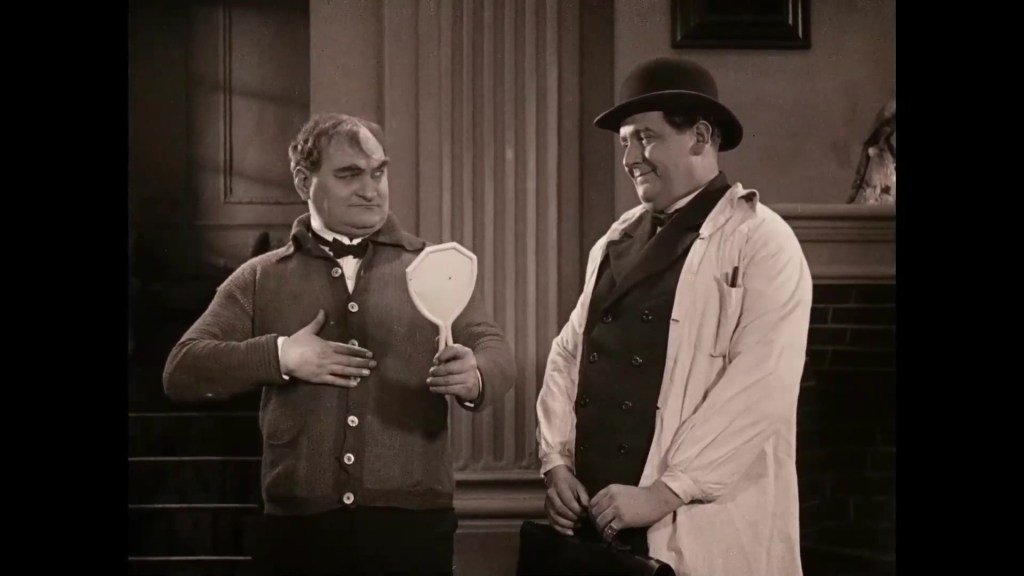

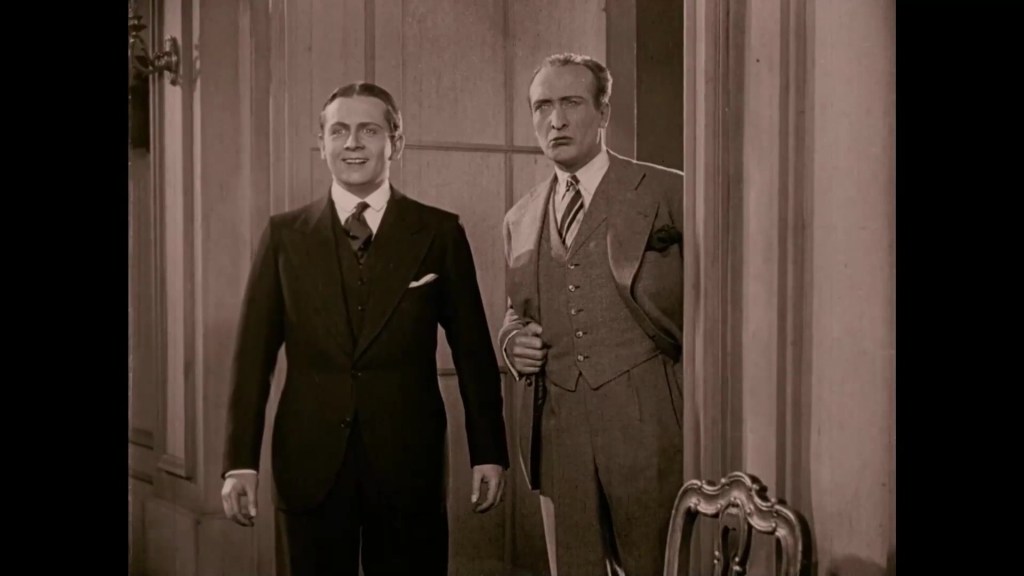

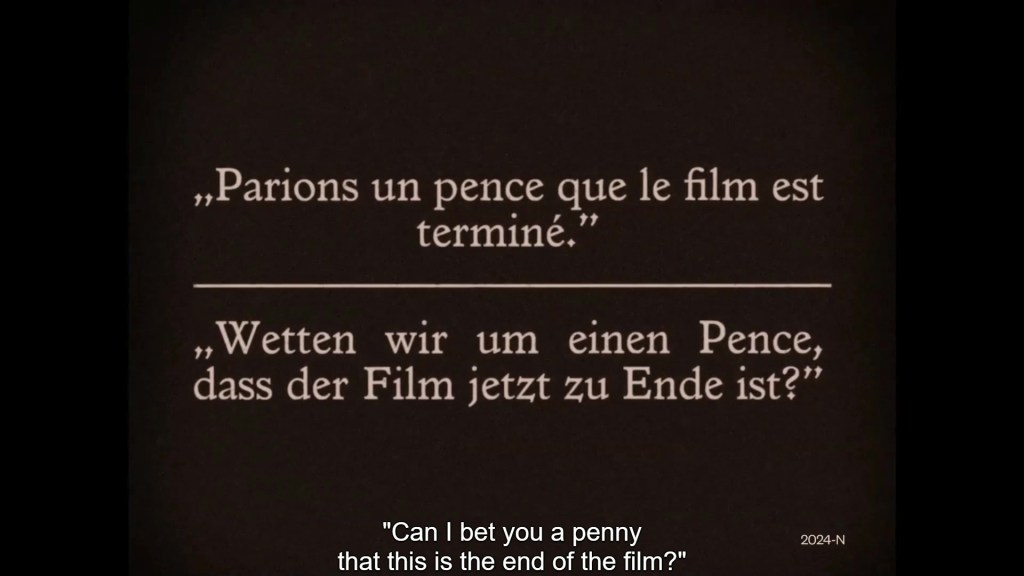

OH: Very simple themes work best because I think they give you the most freedom as a curator to explore things. And it makes the programme varied enough that you don’t have the feeling you’re watching the same film or variations on the same film. In Bonn this year, for example, we had films themed around the mountains or the sea, or films about filmmaking. On the first Friday we had two feature films where one of the main characters is blind, at least for part of the film. Just finding these little connections allows you to put very disparate films together. And in Bologna I had a couple of country-based programmes. For example, I combined a Swiss feature film, which picked up on the hype of the very first Winter Olympics, with an Arnold Fanck short film that was shot in Switzerland, and with a newsreel showing the last Turkish caliph in Swiss exile. I also did a Russian-themed programme, where I started with newsreel footage of the funeral of Lenin in 1924, then some rare footage of Anna Pavlova dancing for Douglas Fairbanks, and finally a completely obscure Russian film, Dvorec i krepost’ (The Palace and the Fortress, 1924). The latter wasn’t an exceptionally good film, but it was very successful in its day. Another major reason to show it was because a pristine print of the German version survived here at the Federal Archives. It was a nitrate print, tinted and toned, which you almost never see in Soviet cinema. So, just because a film may not be particularly good, this doesn’t mean there still isn’t a good reason to show it. The experience is what counts. And I am always grateful when people talk about how well the programme worked afterwards.

PC: Do you always have to consider the specific copies of films you want to show?

OH: Yes. It’s not just a question of curating film titles. You’re really curating film prints. There can be any number of good reasons to show a film. It could be we just really like the film. Or we know that where a particularly good print is located. Or we have determined the film to be in the public domain, so we didn’t have to pay any exorbitant fees to third-party copyright holders to show it. The list goes on.

PC: Does this aspect of organization differ between festivals?

OH: My experiences as a curator are very different for Bologna and for Bonn. Bologna is probably the most important film heritage festival in Europe, if not the world, and I’m just one of many curators. And there are other people on staff that take care of specific things. So, here I don’t book the prints or clear the screening rights myself because there are other people who take care of that. Whereas in Bonn, where we are a comparatively small team, we curators also liaise with archival loans departments or distributors, and negotiate with the rights holders directly. So, while programming for both festivals has a lot of similarities on the one hand, there are also differences. In the case of Bonn, this is particularly because of the hybrid format, live and streamed, which means we are very conscious about finding films that we can stream online without any issues. This form of digital accessibility is very important for the festival because it brings our programme to a much larger audience.

PC: Does digital technology pose extra problems for you, or are there advantages?

OH: There are pros and cons in every case. I’m not one of these dogmatic people who say film must always be shown on film. I think digital is a fantastic tool for making films available. And digital technology has enabled restorations of films that would never have been possible solely through analogue means. So I’m very grateful for that. From a technical perspective for us as a festival, the great thing about digital projection is this ability to record music live, because you’re guaranteed that at the end of the process it will sync up with the image perfectly. Whereas with an analogue projection you never know. So, we haven’t risked it yet – yet! Anything we screen on 35mm, we pre-record the music for the streamed version in the theatre auditorium at the cultural centre where our festival office is based. This usually takes place in the afternoon before the screening.

PC: You mentioned the rights issue being another complicating factor. What are the challenges this aspect poses for curatorship?

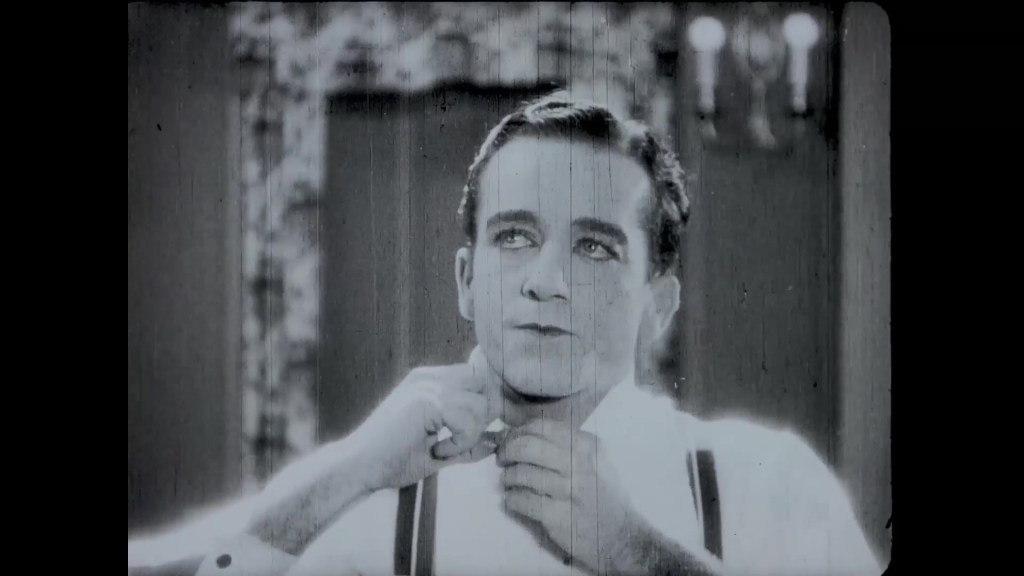

OH: For Bonn, we will focus a lot on films that are deemed out of copyright or in the public domain, which can simplify matters somewhat. But we have made good experiences with some copyright holders such as the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung (e.g. for Der Berg des Schicksals [1924]) or the Fondation Jérôme Seydoux-Pathé (e.g. for La Femme et le pantin [1929]). The point is that we need to ensure that we have great films on our programme, but it often takes time until we know for definite that we can present a film on-site and online without any big repercussions. There are always exceptions. This year we closed the on-site festival with The Black Pirate [1926] in MoMA’s beautiful new restoration. We didn’t pass up on it even though it wasn’t possible for us to stream it in the end, because we knew it would work perfectly for our open-air format with the huge screen and live music. Thinking about it pragmatically, I’m sure there will be a Blu-ray release of MoMA’s restoration at some point in time, and people can see it at home then.

PC: As a curator, how do you see the relationship between the festival as offered on-site and the festival presented online?

OH: It’s a difficult balance. This year we streamed ten of the twenty-one films we screened at our on-site festival, so one each day, which I think is manageable, both for us organizers as well as for the viewers. We’ve had more films online in past editions, but at some point it just becomes too much for people to actually sit and follow at home. I think we made a good call when we decided not to stream any of the short films. Because you also want to make sure people come to the live shows, and that only at the live festival do you get the full programme. And of course, online and on-site are just very, very different experiences.

PC: Does the hybrid format of a festival change how the films are received?

OH: Yes. It’s always fascinating when live and online audiences have totally different opinions of the same films. For example, last year we screened Pozdorovljaju z perechodom [Congratulation on your Promotion, 1932], a very obscure Ukrainian children’s movie. We chose it for various reasons, including to show our solidarity with the Ukrainian people. But it’s the work of a completely unknown female director, Їvha Hryhorovyč, so it was a real rediscovery. It also isn’t a great film. Our live screening wasn’t one of the better attended, and the reception was rather lukewarm, but we still had comparatively strong streaming figures. This year, both yourself and Paul Joyce wrote very positive reviews about Jûjiro [1928], the Japanese film that we screened. But I had people coming up to me after the screening in Bonn who couldn’t fathom why we had screened it. Maybe it was just the vibe of the live screening, or maybe the film was just too intense for them. So, I was so glad to read your reviews later where you really praised the film.

PC: Since the easing of restrictions after the various lockdowns, some festivals have cut back on the amount of online content they offer. For example, the Ufa-Filmnächte festival in Berlin streamed their films for free during the pandemic and beyond, until 2023 – but now this service has ceased. What do you think the future is for the streaming of festivals more generally? Is it a sustainable model for the future?

OH: Well, it’s hard to give a kind of all-encompassing answer to that question. I think from the outset that were very different attitudes from festivals toward streaming. For example, on one extreme you had festivals which took the attitude of waiting until the pandemic was over so they could take place as on-site events as normal. Then you had others that went completely virtual. And others which tried to offer the best of both worlds while still respecting the increased health and safety restrictions that were in place at the time. When the restrictions were eventually lifted, several festivals that had been quick to offer virtual solutions just as quickly gave that up.

PC: Pordenone is one of the few major festivals to have continued a major streaming service.

OH: Yes. I think what festivals like Pordenone experienced with the streaming was that it tapped into potential new audiences. When Pordenone staged its “online limited edition” as a replacement for that year’s on-site festival, which couldn’t take place because of the pandemic, they ended up with something like twice as many subscribers as they would normally have accredited guests.

PC: And the Bonn model?

OH: At Bonn, of course, we’re somewhat different to, say, Pordenone, because no one pays any money to see the films, either at the on-site festival or online. This not only means we don’t have any revenue, but can also lead to other obstacles. For example, some people are concerned about piracy, and there’s an attitude that if something is made available for free then that also makes it easier to steal. On the one hand, I can understand the concern, as a lot of money goes into restoring the films and the institutions might be under pressure to try to recoup some of that money, but I also think it’s a bit of a shame as it restricts access to cultural heritage. And, of course, it’s not free for us to make the films available for free. On the contrary. The streaming platform is a major cost factor, but it’s just one of several. There’s also the additional cost of the sound recordist, for example, which we wouldn’t have if we were a purely on-site festival.

PC: Do you hope to be able to keep your hybrid format in the future?

OH: Bonn is maybe a relatively small silent film festival compared to the likes of Pordenone, but our hybrid approach has got us on people’s radars, and this is why we will continue to offer films for free streaming online as long as we can. But there may come a point in time where it won’t be feasible anymore.

PC: Is there a tension between wanting to promote film heritage and the need to restrict access to content?

OH: This is the irony. Just because more and more things are available digitally doesn’t make it easier for us. Actually, it can sometimes feel like the contrary. In addition to the aforementioned concerns about piracy, the additional costs for the provision of streaming materials and rights can sometimes be prohibitive. In others, it’s just not possible to license worldwide. While we strive to make everything we stream available worldwide, we’ve had to make exceptions in a limited number of cases where we could only be granted streaming rights for Germany. In the case of one film we were very keen to show in Bonn last year, we were compelled to drop it in the end because the archive which held the film had just signed a Blu-ray deal with a distributor in the US. This deal ruled out the possibility for us to stream the film. Nowadays, Blu-ray companies are very savvy about acquiring streaming rights for their territories as well.

PC: Given all these factors, I presume that offering a streaming service puts added pressure on the staff and resources of festivals. Is that your experience at Bonn?

OH: It’s a massive strain, not only in terms of the additional man-power and know-how required, but also because it all has to be carried out within the existing budgetary framework, which is still based on pre-pandemic times before streaming became a thing. That’s why for a number of years we had to forego a printed brochure. We only brought it back this year because we ran a successful crowdfunding campaign to finance it. Costs are forever going up, while funding for cultural endeavours is constantly at risk of being reduced or cut altogether.

PC: How does the actual process, the workflow, function for streaming films? Who handles it all?

OH: In the first place, we don’t do live streaming. Films are not streamed online simultaneous to live screening. We have everything planned out and prepared in advance, and when the music recording is ready, I put audio and video together and we upload the films to the streaming platform’s back-end server. It helps that I had a background working a lot with digital file wrangling and AV mastering and so on. I do all that myself, which I suppose is a bit crazy. But it’s also a bit of a guilty pleasure, so I don’t complain about it too much! It’s also positive in the sense that it helps build trust with the lending institutions. I can guarantee them that the video files don’t leave my hands until the point in time when they are uploaded to the platform’s server. The musicians and the subtitler receive heavily compressed screeners with a big fat time code rendered into them. No-one gets the clean video image apart from the server. So, it’s useful, particularly when we were dealing with new institutions, to be able to show them the workflow and demonstrate that we take active steps to restrict the possibilities of things being pirated as much as we can.

PC: From a different perspective, there are now major archives – like the Danish Film Institute or the Swedish Film Institute – that offer a lot of their holdings for free online. But these versions are often entirely without soundtrack or accompanying material. They’re not offering a full aesthetic experience, they are just offering access. Is this an entirely different model to that of festival streaming?

OH: What these institutes offer online is an unmediated form of access, at least in comparison to a cinema or festival screening. Of course, as a research tool, these platforms can be considered veritable goldmines, and I have benefitted a LOT from them in my own curatorial work. It’s a fantastic service, but not always a pleasurable viewing experience due to the lack of music or English subtitles in applicable cases. Putting silent films online without music might be good for certain formats – non-fiction, short form – but not for features. My dream would be that we make as many of the films that we have presented in the Bonn programme available online permanently – with the music. The problem is that, while the films have already been digitized and the soundtracks have already been recorded, there are still additional expenses involved in making the films available online outside of the festival streaming period. And unfortunately there are next to no funding opportunities for such endeavours.

PC: Again, I wonder how satisfying this model would be. Do you feel Bonn should have this kind of permanent presence, this recorded archive of live events? Isn’t there something uncapturable about a festival? How do you look back at what you achieved each year?

OH: As soon as the festival’s over, your mind is usually already pre-occupied with the next festival. But there’s a period of a couple of weeks where I do the digital housekeeping, backing up the master audio files and deleting all the huge video files amassed in the run up to and during the festival, but not before running off low quality reference videos to send to the musicians and to the archives for posterity. Doing this puts me back in the festival for a little while. I listen to the music again and think how nice it was, and that it’s really a pity that this material can only be experienced by audiences for a fleeting moment – and then it’s gone. But that’s cinema, right?