The third day of my cultural smash-and-grab was the busiest. Three screenings: one illustrated talk, two shorts, and one feature…

Sunday 15 September 2024: Salle Georges Franju, 2.30pm

The first event of the day was a “Ciné-conférence” by Elodie Tamayo, devoted to Gance’s unfinished project Ecce Homo (1918). Gance wrote this screenplay in March-April 1918 and began shooting that same month around Nice. His cast included Albert t’Serstevens as Novalic, a prophet who is ridiculed by society and committed to a mental asylum. His one true disciple, Geneviève d’Arc (Maryse Dauvray) reads his testament, “Le Royaume de la Terre”, and traces Novalic to his asylum where she hopes to help him recover his sanity. Parallel to this social/religious story is the melodrama of Geneviève’s infatuation for Rumph (Sylvio De Pedrelli), Novalic’s son from a liaison with an Indian woman, together with Rumph’s romance with Oréor (Dourga), an orphaned girl from the east. Though Novalic’s written testament is falsified and ultimately destroyed as a result of the conflict between Geneviève and Rumph, at the end of the film the prophet returns to his senses and plans to use cinema to make his message more readily understood. Ecce Homo was to end with the writing not of a book, but of a screenplay: the blueprint, one might imagine, for the very film we have just watched. Novalic declares to his contemporaries:

You haven’t understood my deeds, you haven’t read my books, you haven’t listened to my words; I am going to try another way. I will use neither the written word nor the spoken word to reach you. I will employ a new language of the eyes, which, unlike other forms of communication, knows no boundaries. Like children, I will show you oversized infants Moving Pictures, and my great secret will be to say simultaneously, and across the whole world, the most profound ideas with the simplest of images. Soon I will etch my dreams across your pupils, like an engraver might animate his work. And I think that this time you will understand me!

Gance abandoned Ecce Homo in May 1918, only a few weeks into its production. He wrote in his notebooks: “I quickly perceive that my subject is too elevated for everything around me, even for my actors, who don’t exude sufficient radioactivity. I’ll kill myself in no time at all if I continue to give this voltage for no purpose.” Miraculously, three hours of 35mm rushes survive from the material shot in April-May 1918. I first saw this material in 2010 and found it utterly fascinating. It was so moving to view not only the evidence of the filmed scenes, but the glimpses of Gance and his crew in-between takes: the director appearing, glancing at the camera, disappearing; the notes about each take – “Good”, “V. good” – chalked on boards at the end of the scene. Seeing this material on the small screen in the archive, I longed to see it projected…

All of which brings us back to the Salles Georges Franju last Sunday. Tamayo’s presentation offers not just extracts from the rushes (digitized in excellent quality), but a rich context in which to understand their significance. Texts by Gance and others were read by Virginie di Ricci, while electronic music was provided by Othman Louati. Tamayo herself presented information on the film’s context, production, and surviving content. I will say more on this shortly, but first and foremost I want to give a flavour of the surviving material.

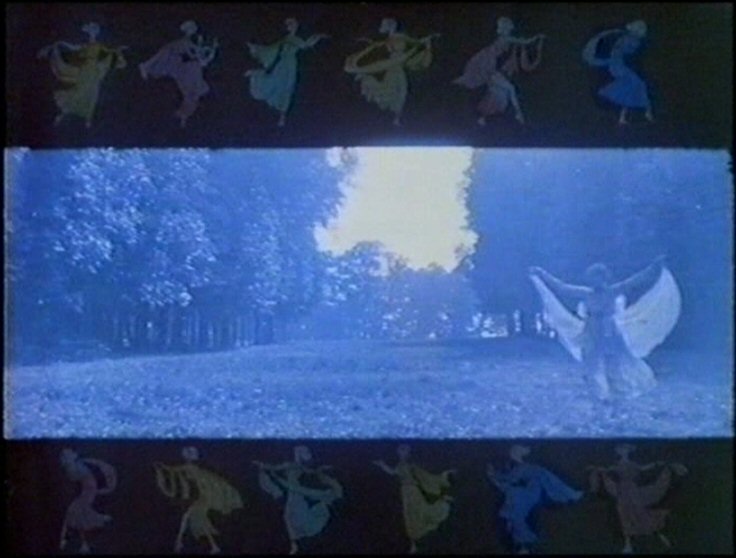

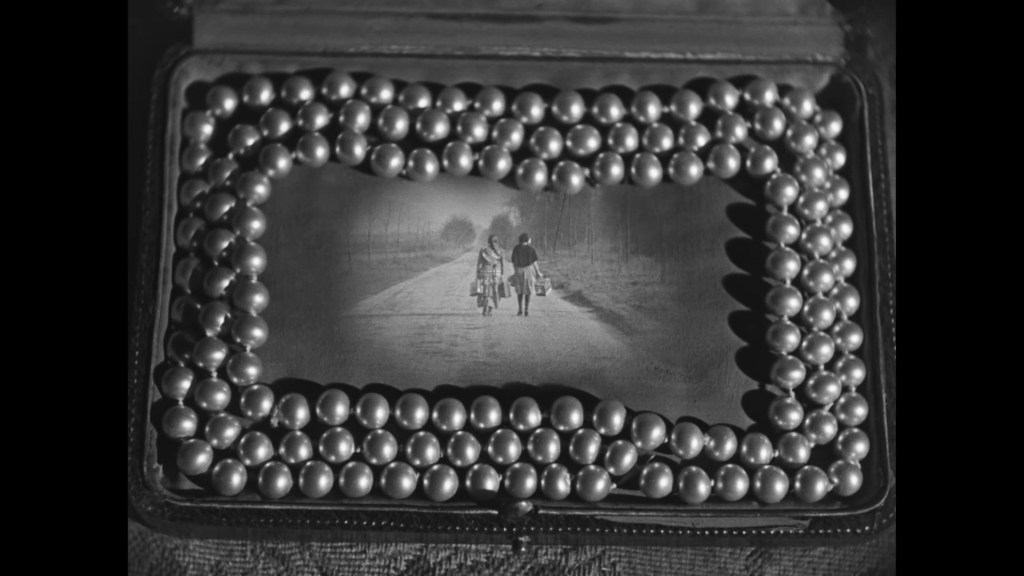

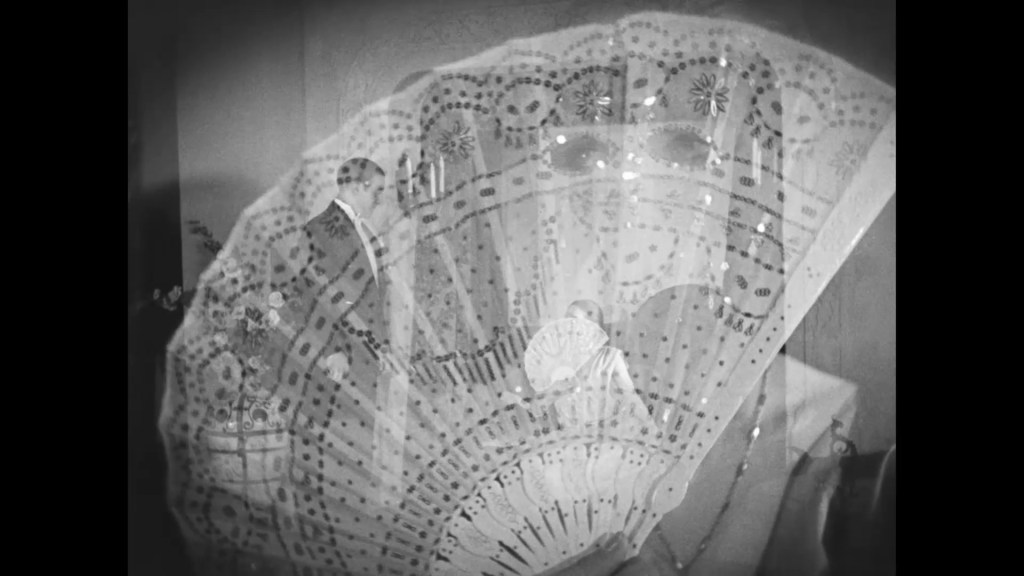

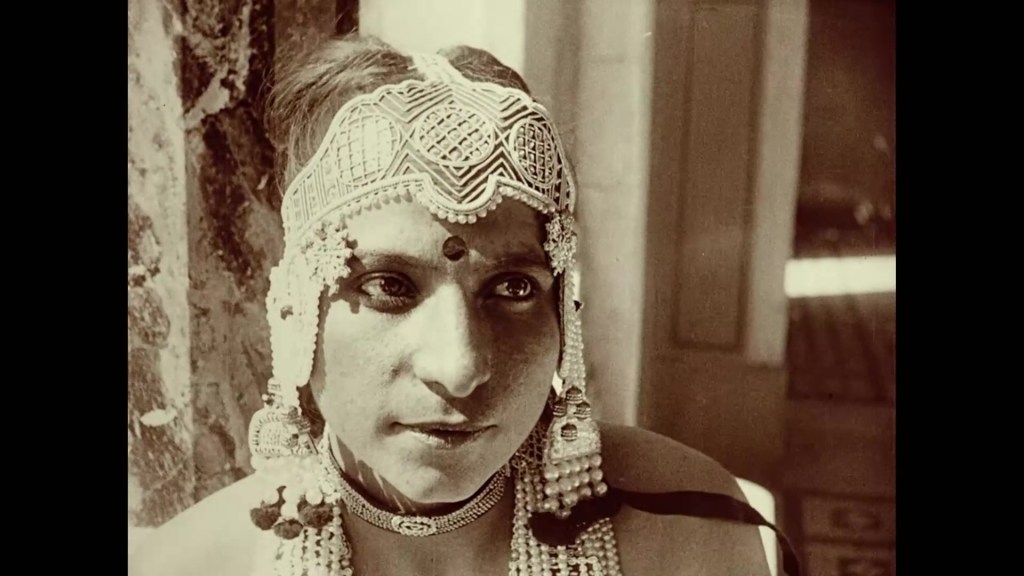

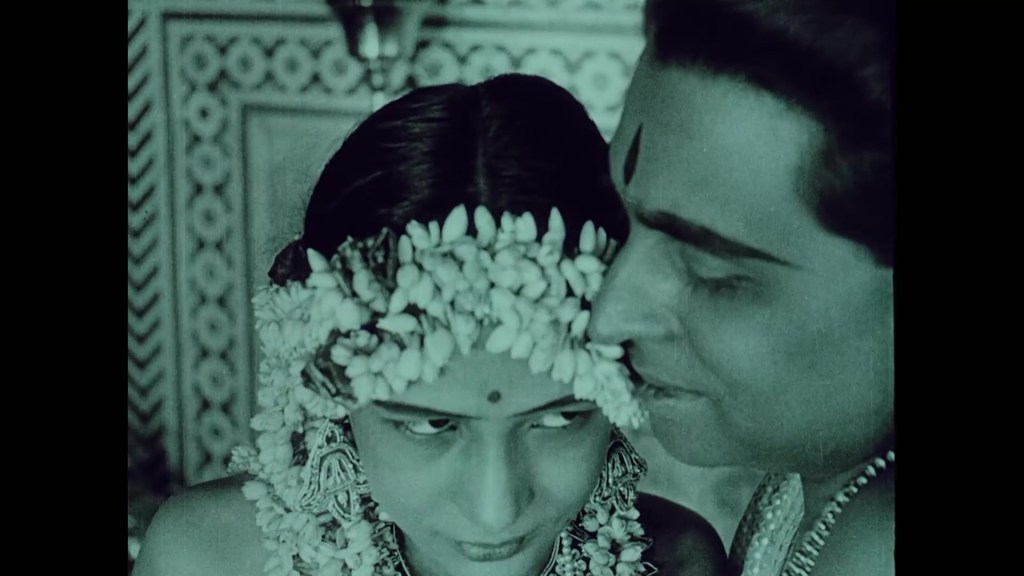

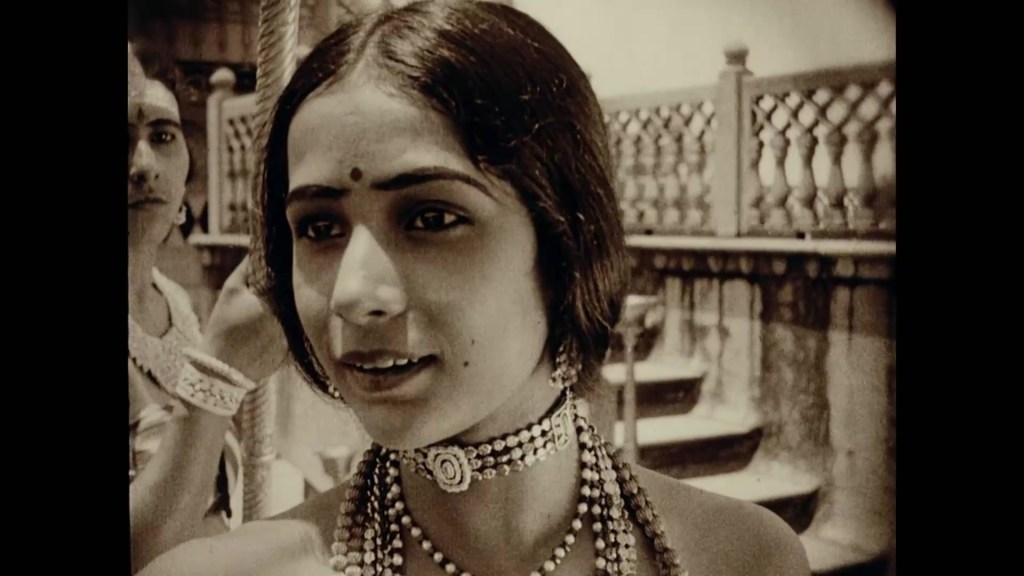

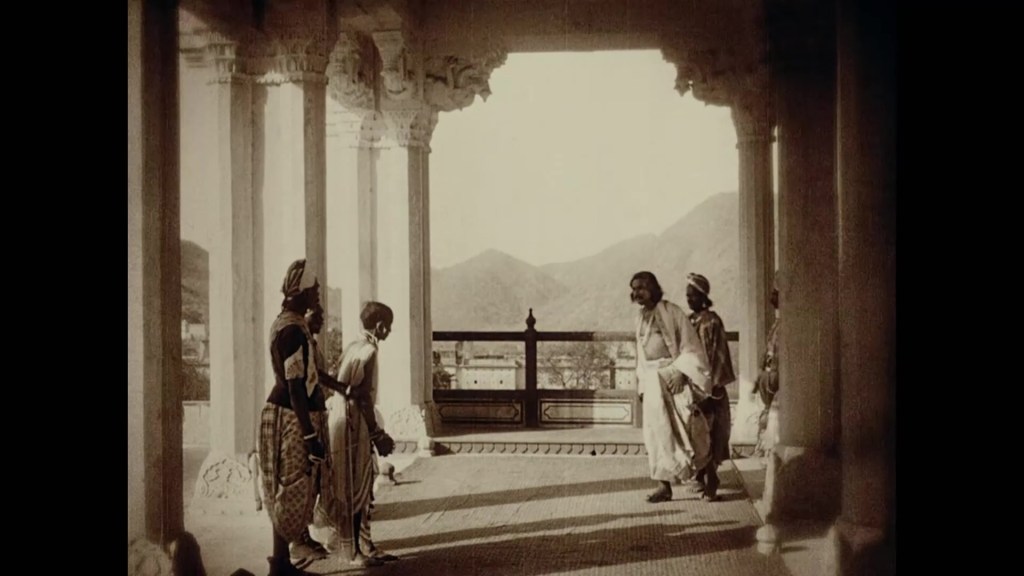

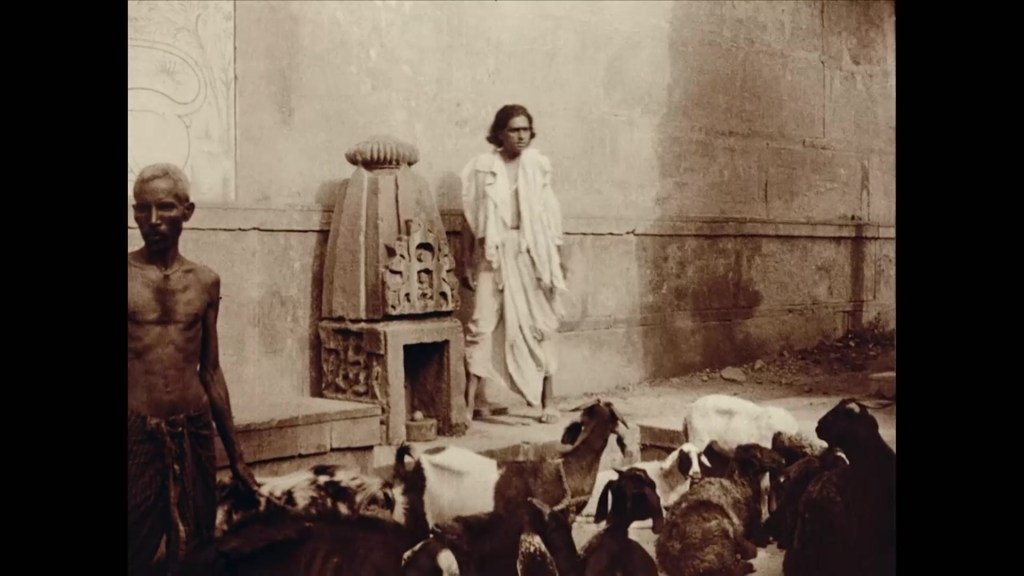

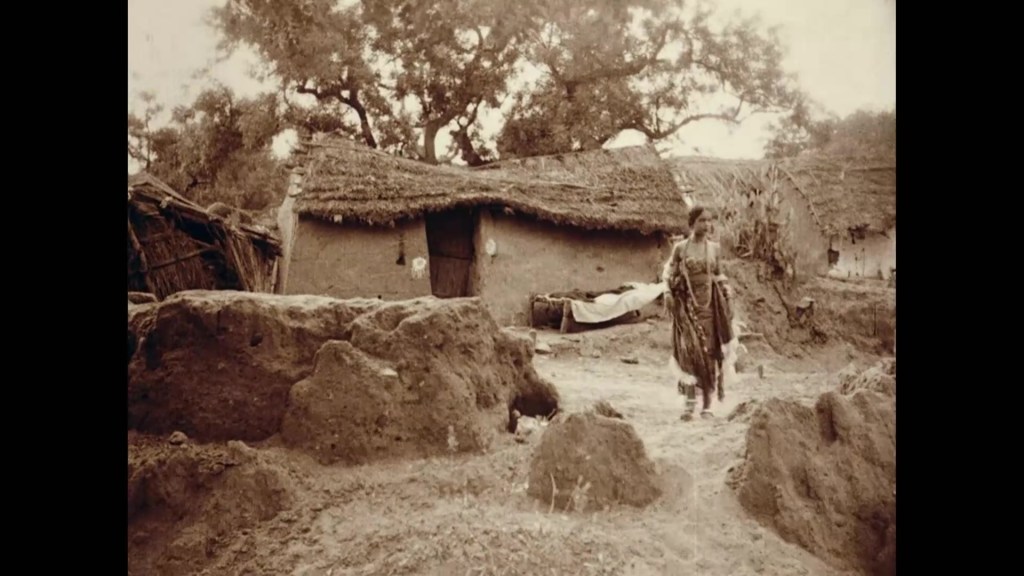

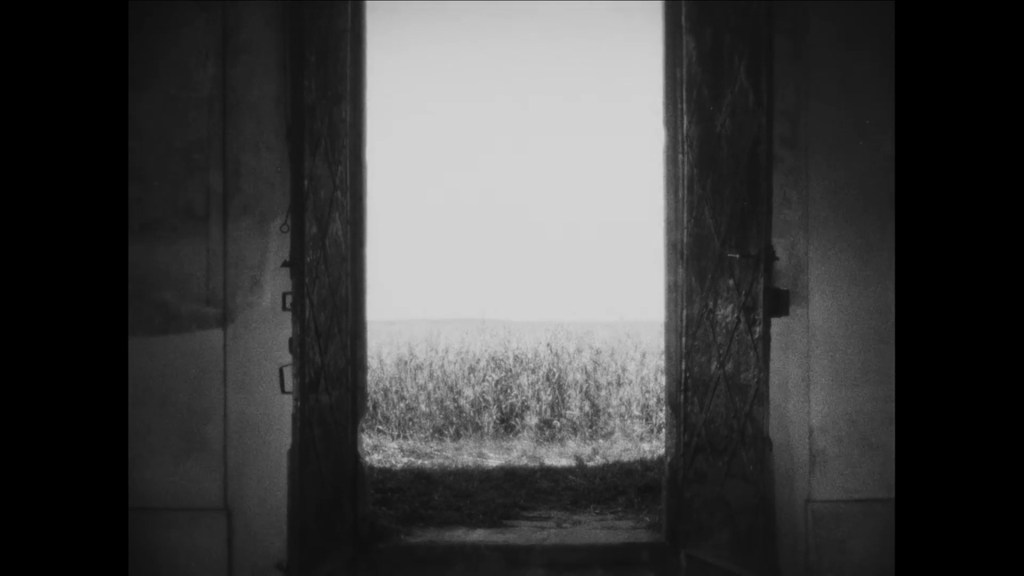

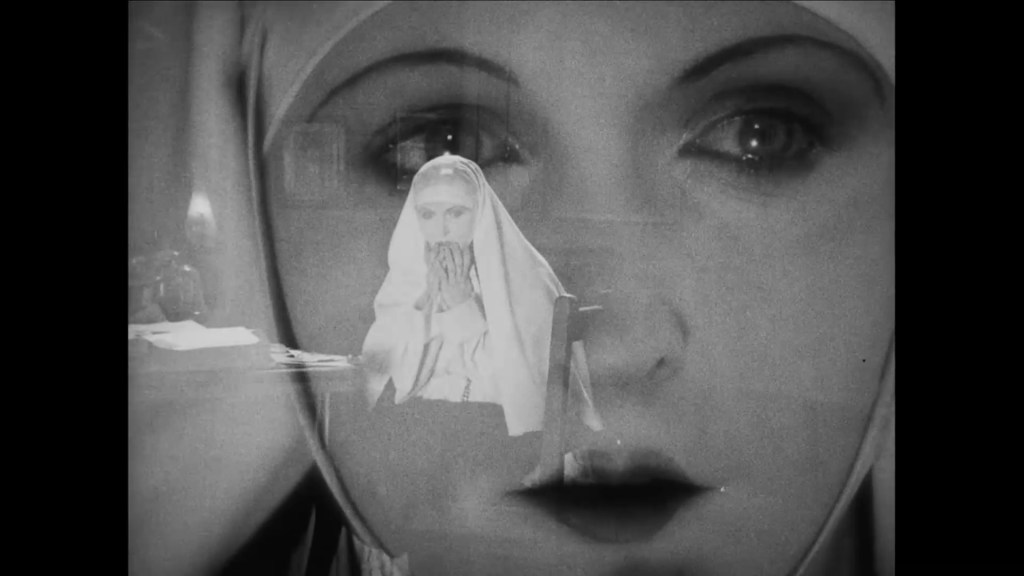

Shot by Léonce-Henri Burel, the surviving footage once more uses the coastal landscapes of the south of France as a luminous stage for the drama. The location doubles, most notably, for the Indian jungle in which we see Oréor’s seductive dance for Rumph. It looks stunning, and seeing this on the big screen was an absolute thrill. I remembered the rough outline of the images, but I was struck anew by their visual quality. There is one faultless superimposed dissolve, for example, which transforms Oréor into a semi-transparent apparition as she begins her dance. Then there is a stunning view of a moonlit clearing in which the half-naked character poses with her veil. Burel’s control of low-key lighting, and Dourga’s extraordinary physicality, are a fabulous combination. Oréor’s dance demonstrates a clear transition from the diaphanous, hand-tinted dance sequence in La Dixième symphonie to Diaz’s subjective visions of Edith in J’accuse. But I think Dourga’s scenes in Ecce Homo are more interesting than either of these sequences: more evocative for the eye, more erotic for the senses.

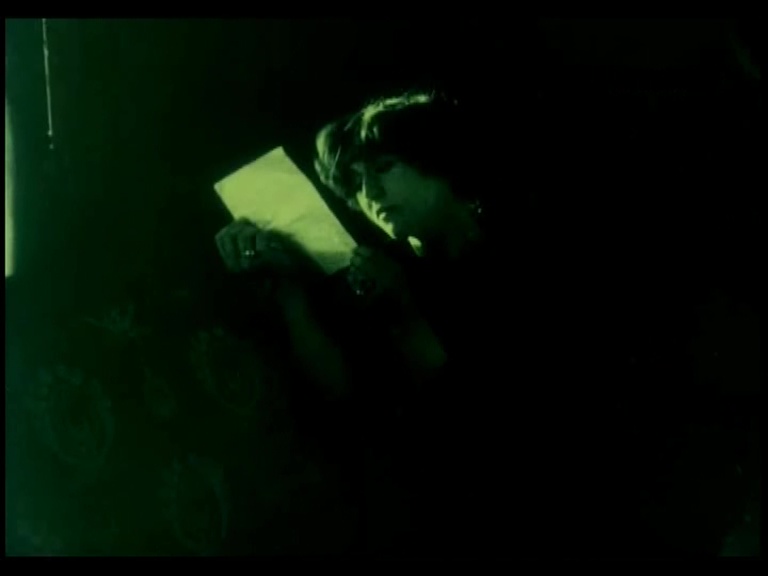

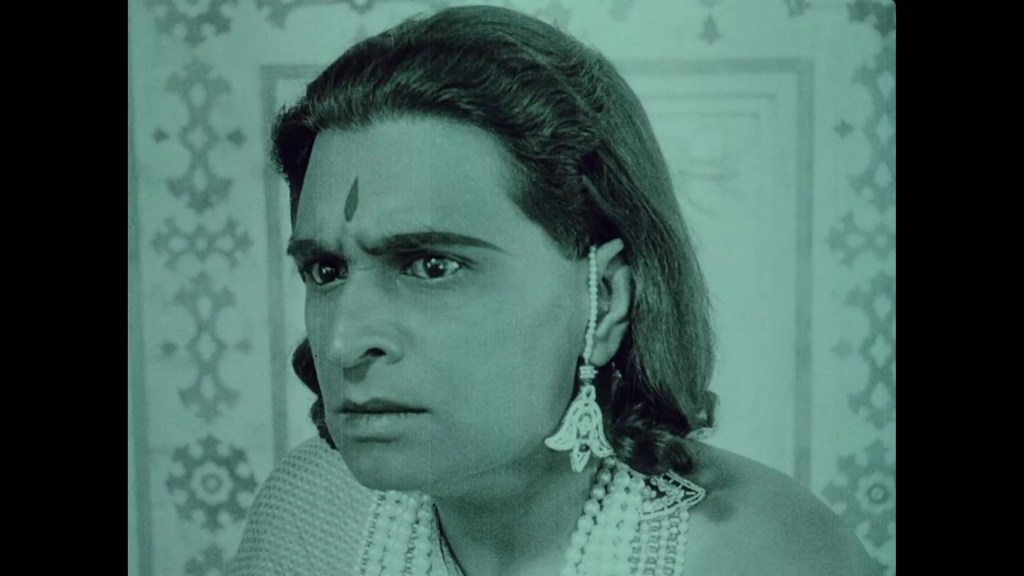

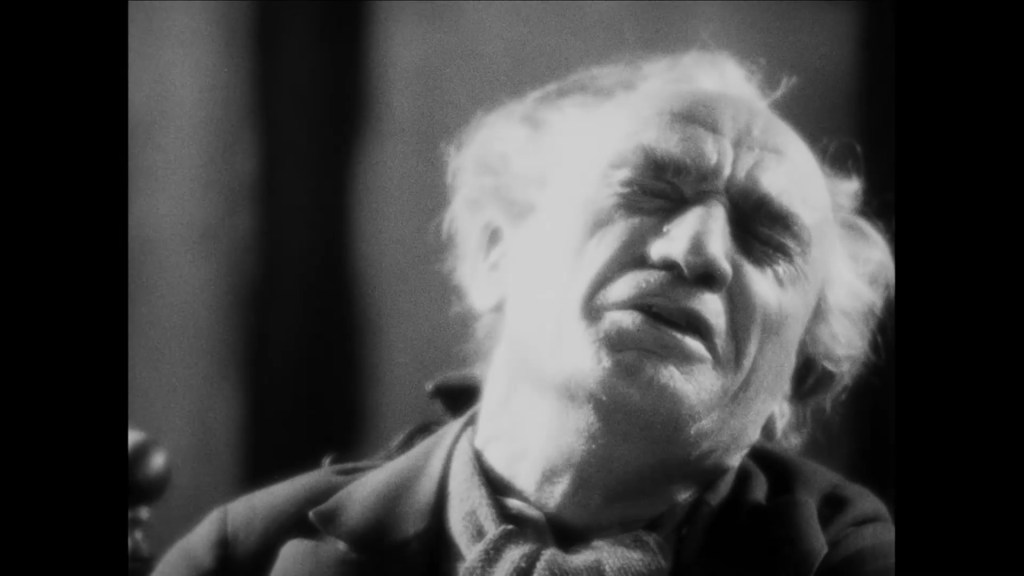

Talking of J’accuse, I found it wonderful to see Maryse Dauvray on the big screen. (When I first saw the rushes of Ecce Homo, I realized that every filmography I had read misattributed her role to another actress!) Gance gives her some beautiful close-ups, and the sight of her reading from Novalic’s testament was so extraordinarily vivid that I found myself crying. My god, the quality of the footage is superb. Yet again, the sheer presence of these images is something miraculous. I wept too at her scenes with Rumph, when she watches him burning copies of “Le Royaume de la Terre”. The sight of the pages billowing like fallen leaves across the ground becomes a moving metaphor for the fate of Gance’s own film.

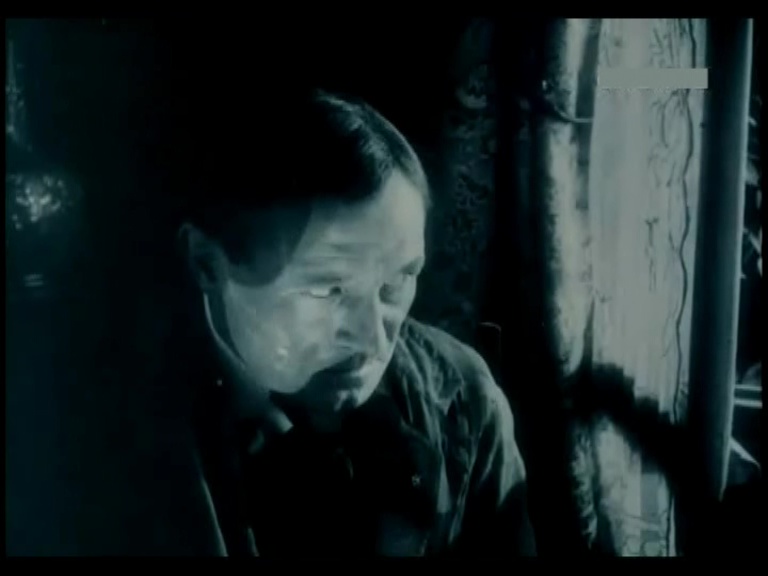

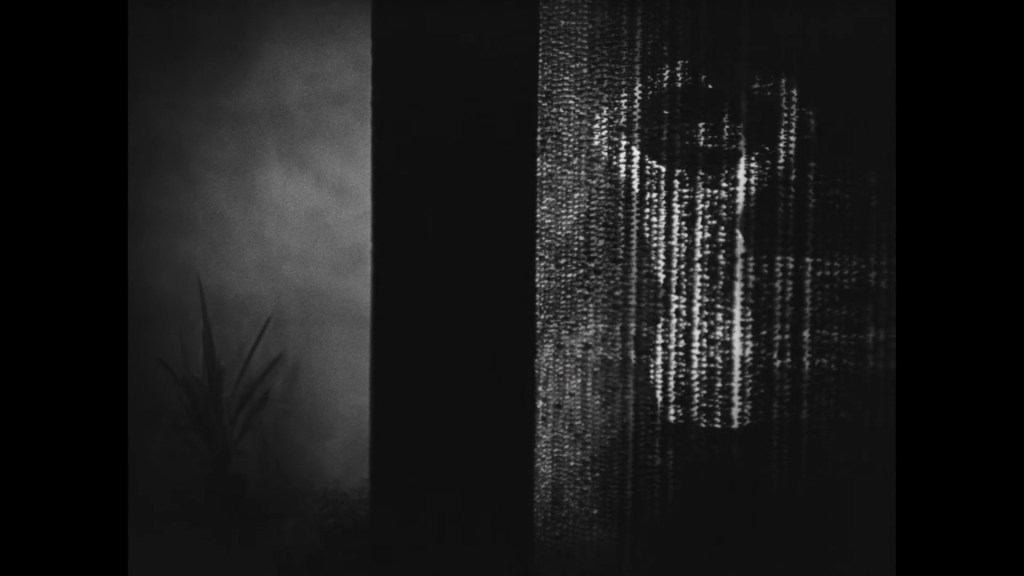

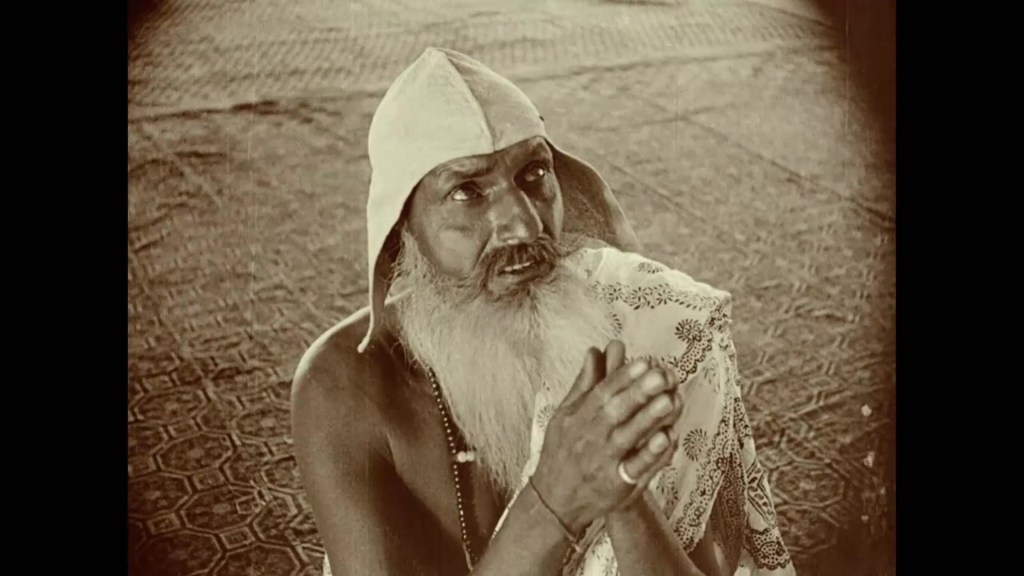

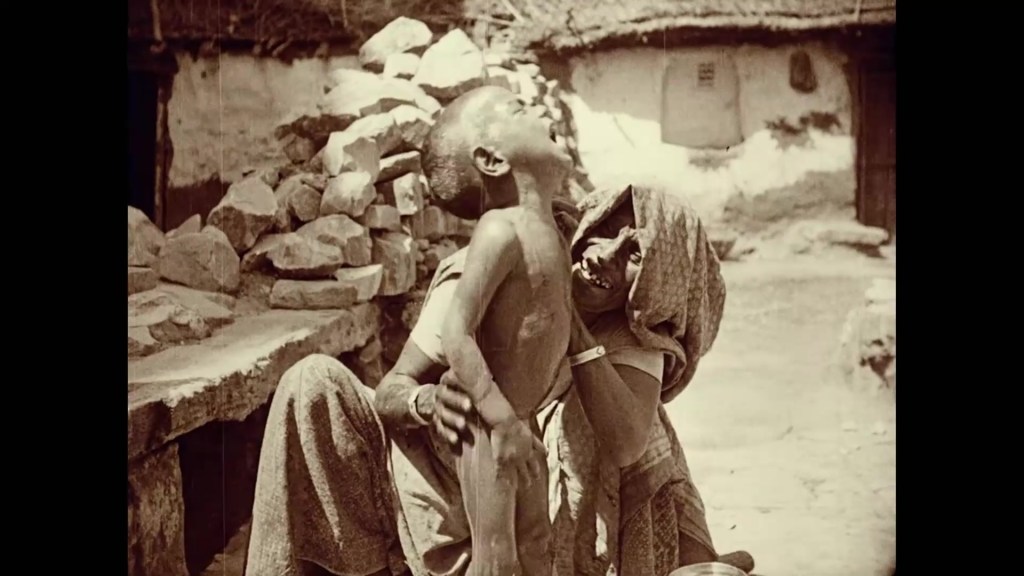

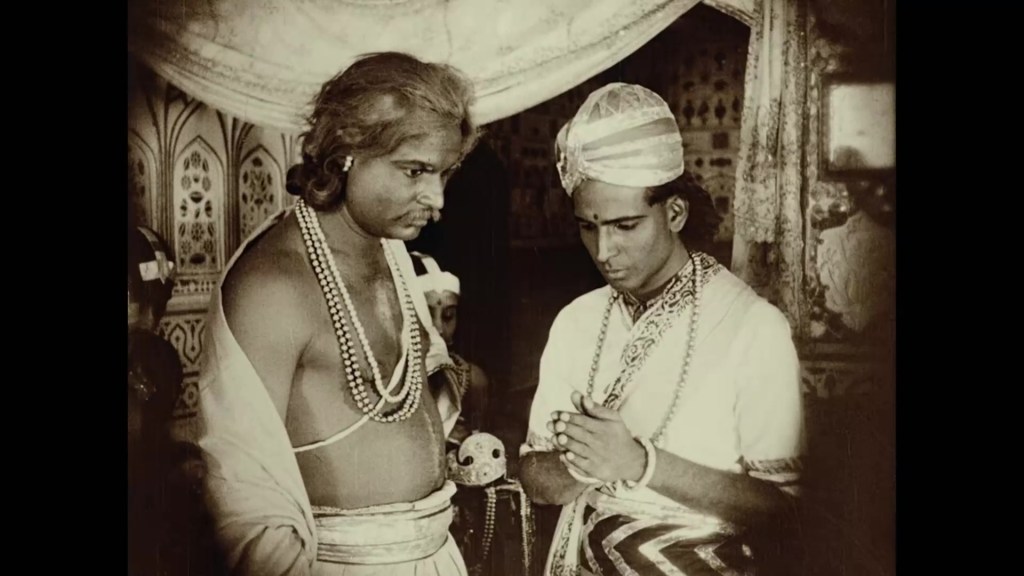

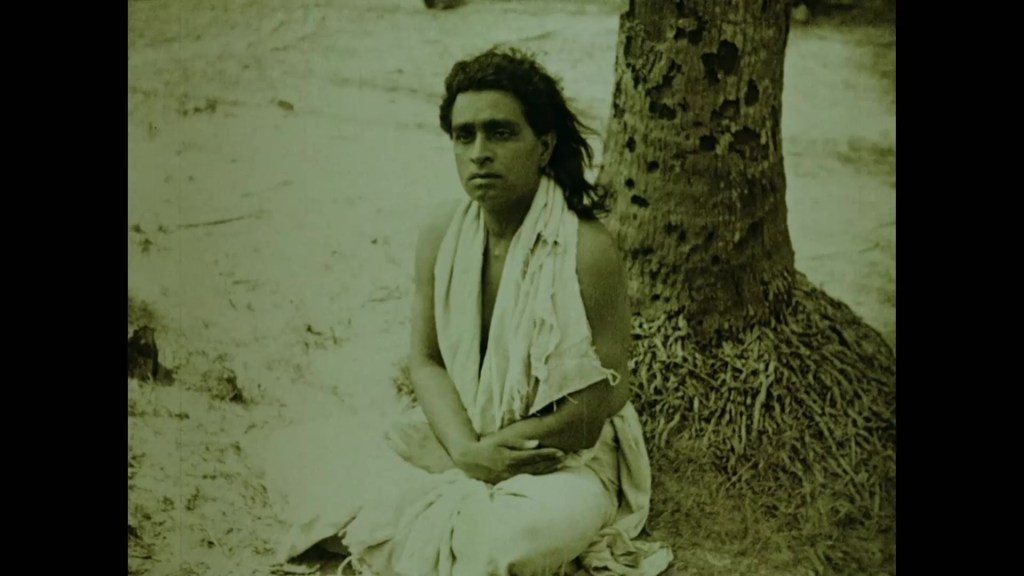

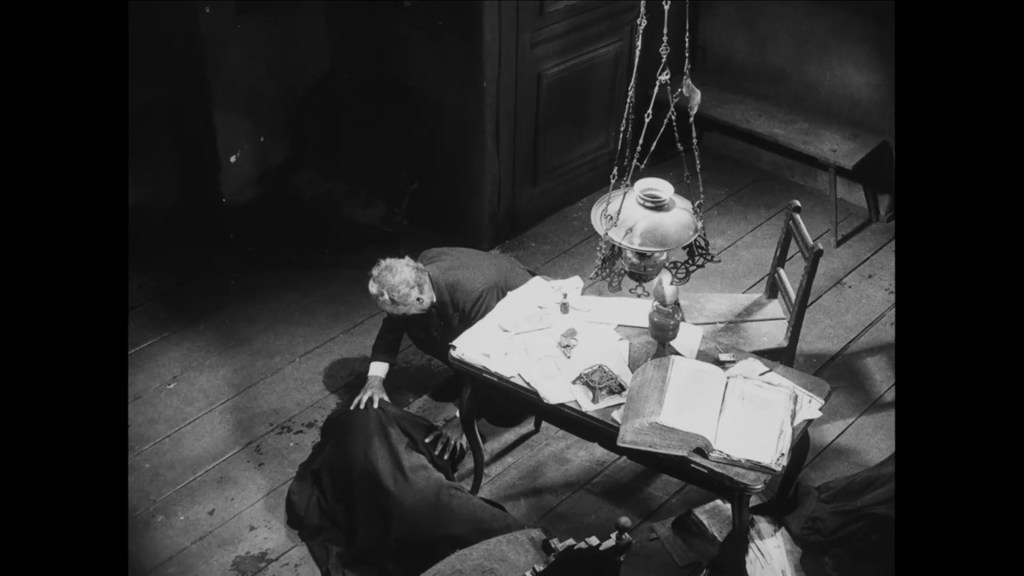

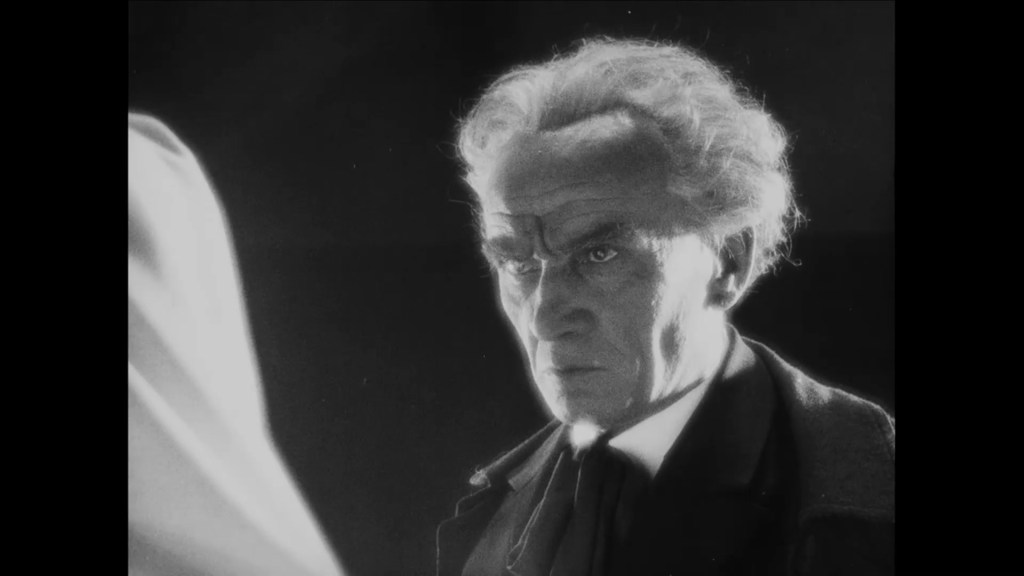

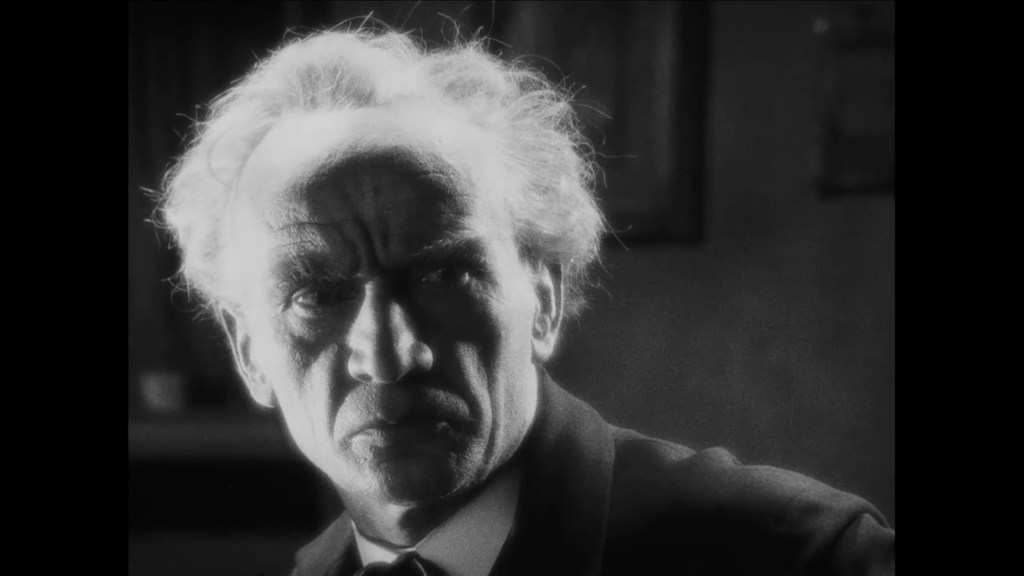

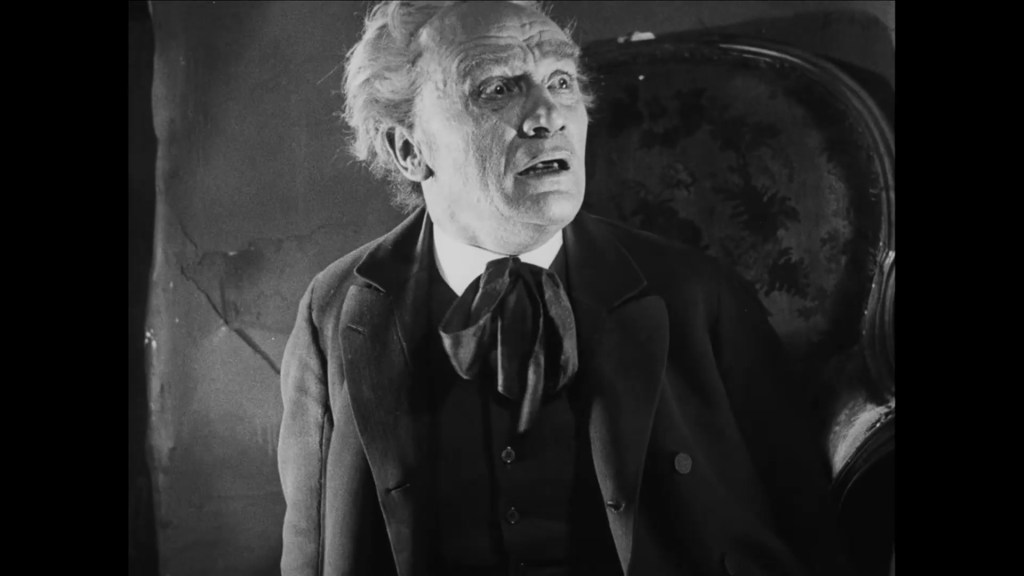

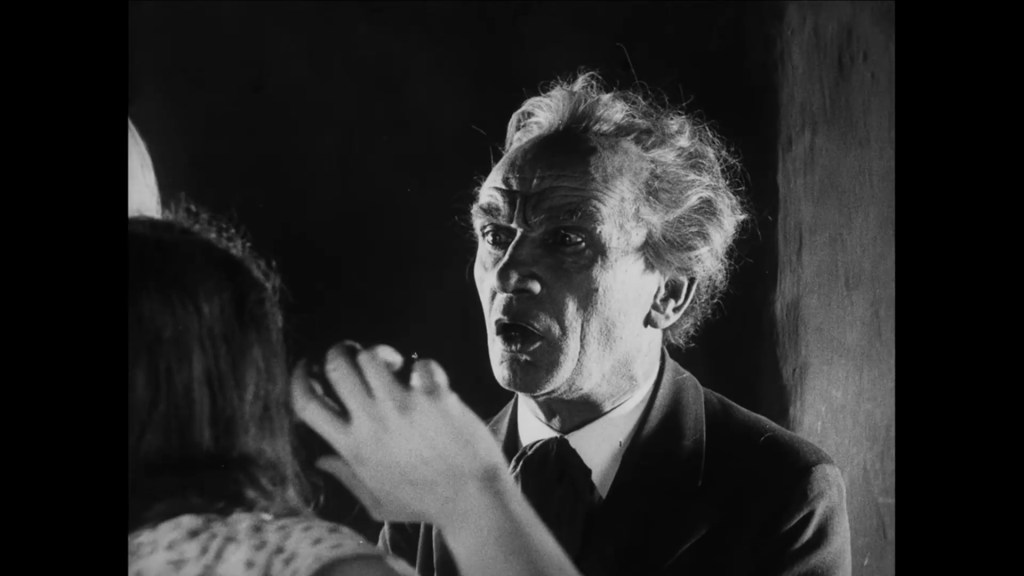

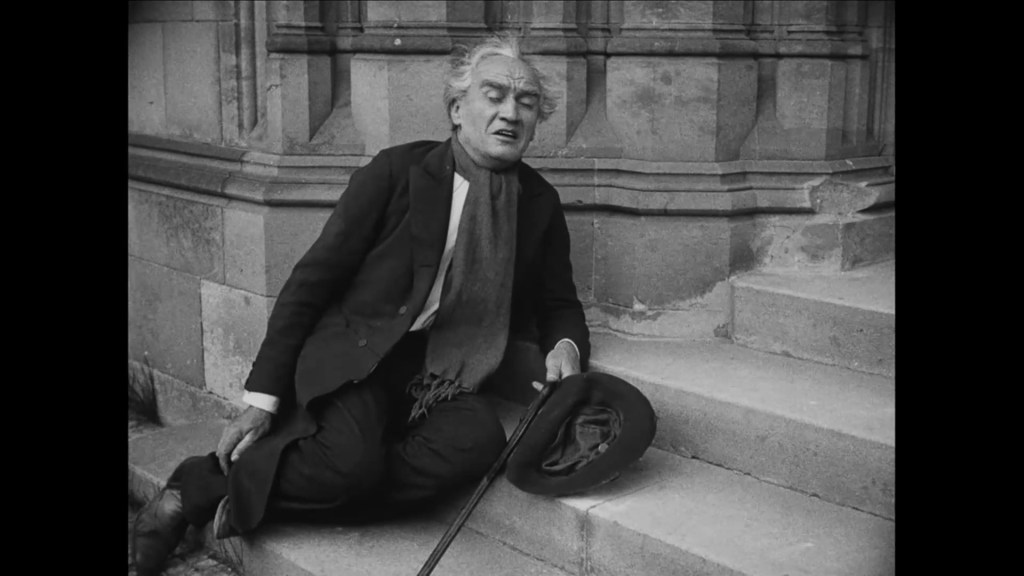

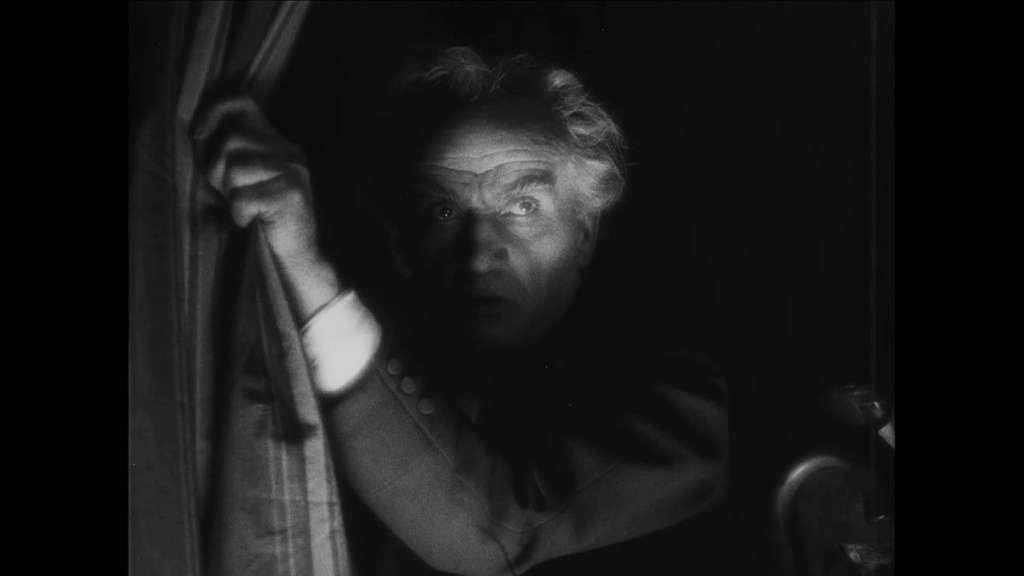

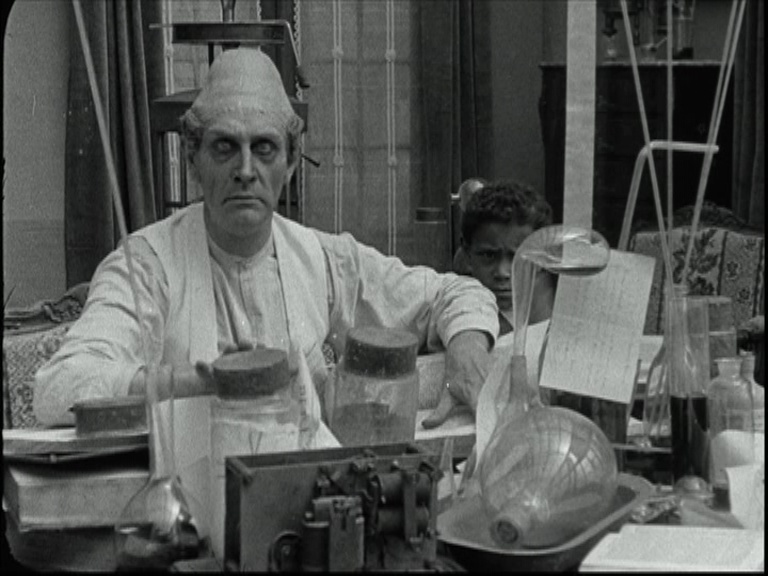

The scenes of t’Serstevens as Novalic are equally striking. He is delightfully corporeal, earthy: we see him shabby and unshaven; he roars with laughter at his own words; he walks backwards, perseveringly circling a tree to bless the insane. There is something touchingly natural and believable about him as a madman. (Something not the case with Gance’s own performance as Novalic in La Fin du Monde, a decade later.) And, as Tamayo pointed out in her talk, Novalic’s fellow inmates on screen are played by the real population of a mental asylum. As well as shots of their collective respect for (and defence of) Novalic, there is a heartbreaking sequence of close-ups of their faces, dissolving from one to another, that is simply extraordinary. Gance had a knack for finding the right faces, and here are dozens of real people, their pasts and their struggles written on the lines of their faces. This is not manipulation but revelation.

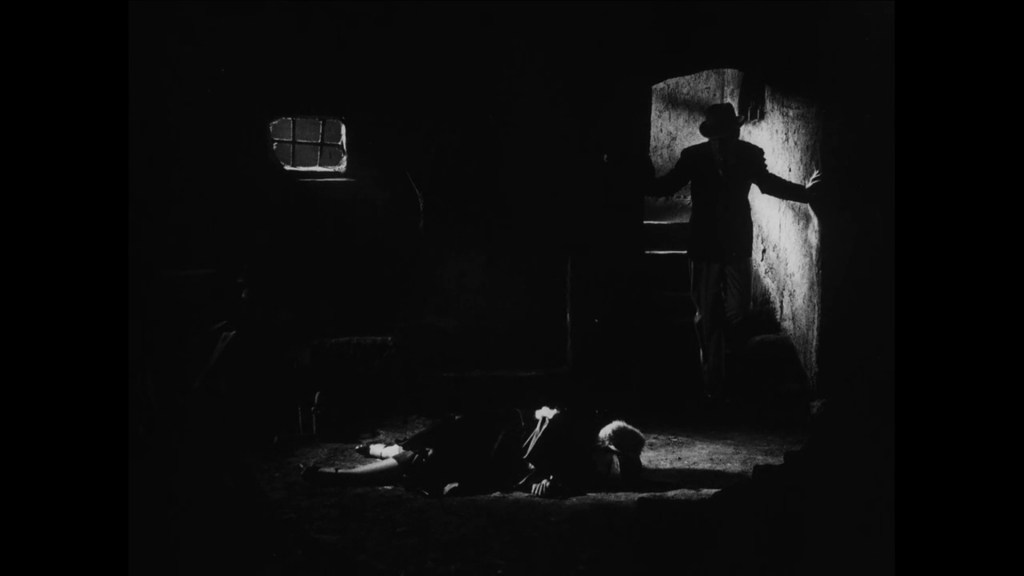

On the relation of Novalic to his time, Gance begins his scenario with a quotation from Ernest Renan: “If the Ideal incarnate returned to Earth tomorrow and offered to lead mankind, he would find himself facing foolishness that must be tamed and malice that must be scoffed at.” Just as we see remarkable images of the Christ-like Novalic behind bars, so the rushes contain lots of footage of the malicious populace – from policemen and soldiers down to bourgeois women and children. Like the vindictive mob that bullies and beats the half-German child in J’accuse, the crowds of Ecce Homo are gleefully nasty: laughing cruelly, pointing at the mad, hurling stones, a swirling mass of malicious derision. Some of the most remarkable scenes to survive include shots of this seething crowd cowering before a cross that rises mysterious up into the camera lens. The doubters are quite literally brought to their knees before the camera. (Seeing these shots again, I also thought that the crucifix resembles the crosshairs of a gun: the camera as weapon!)

Central to the success of Tamayo’s ciné-conférence is her careful shaping and framing of this original footage. The event began with the entire auditorium being cast into darkness (the Salle Franju screen disappearing in a swirl of mobile walls), after which we hear the opening words of Gance’s scenario:

At that time, men were so tired that they could not raise their eyes higher than the roofs of banks or the chimneys of factories. The war had just crushed the most beautiful energies, and the last beliefs in a just God had been swept away in a tempest of hatred. The heart of the world was annihilated by pain, by tears, and by blood that had been shed in vain.

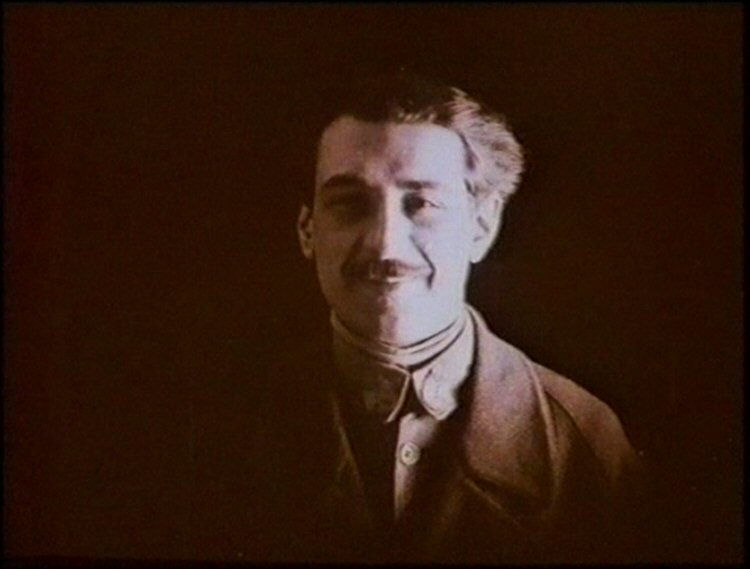

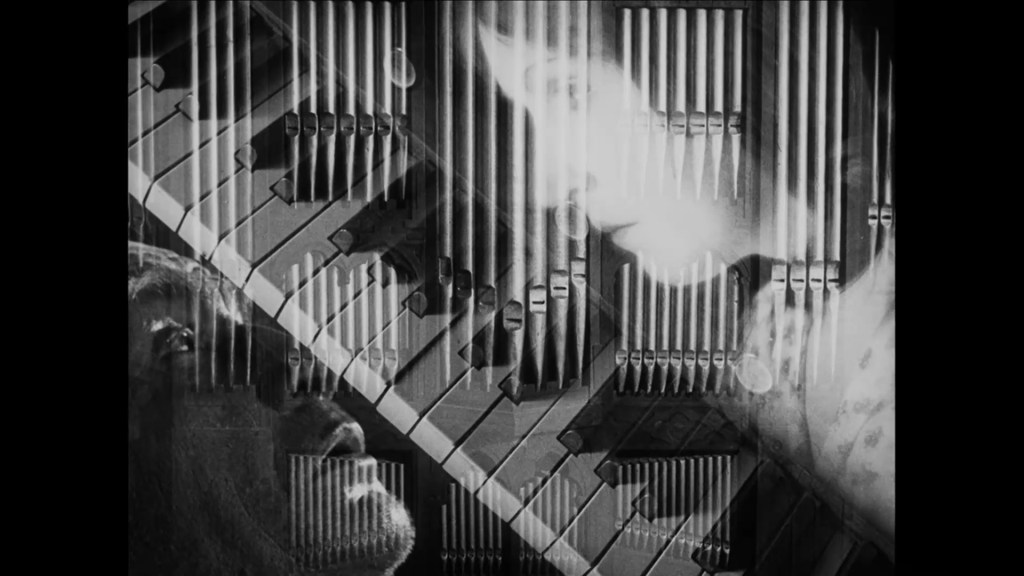

After this prologue in darkness, there is a wonderful coup de théâtre as the screen reappears to offer us the first image: Albert t’Serstevens as Novalic. Presented as the introduction to the ciné-conférence, Gance’s text acts as a frame not only for the plot of Ecce Homo but also for the production itself. “At that time” refers to 1918, which Gance’s fiction imagines as the past – and which is now, a century later, truly the distant past. Reading the scenario, one becomes aware that the “I” of the text is not Gance but an imagined future narrator. Ecce Homo was thus imagined as a kind of extended flashback, a parable from the world to come. The scenario’s narrator reveals that he witnessed the whole story one evening in the “moving stained-glass windows” of a future cathedral. The idea of “moving stained-glass” evokes the kind of visionary projects that continually animated Gance’s artistic imagination. Around 1913, he envisioned “orgues lumineuses”, synaesthetic instruments which could produce turn sound into image, music into light, on giant screens. In 1918, Ecce Homo imagines a future technology – a future culture – that offers “moving stained-glass windows”: a kind of hallucinatory architecture, an immersive visuality, kaleidoscopic and coloured, that shapes and reshapes itself for the beholder, spelling out the visual narrative of Novalic’s life and message.

In his notes for Ecce Homo, Gance quotes from Oscar Wilde’s De Profondis: “Every single work of art is the fulfilment of a prophecy; for every work of art is the conversion of an idea into an image.” It is this process that Gance tried to realize in his film (in all his films, one might say). It is also an idea taken up in Tamayo’s ciné-conférence. Her finale uses AI images (created by Érik Bullot and David Legrand), together with ink drawings (by Jean-Marc Musial) to evoke the futuristic framing of Ecce Homo. In this sequence, images from the past are transformed via the AI imagination: here is a luminous cathedral, glass glowing, melting, crystalizing; here are spectators, cameramen, vehicles, crowds coming and going; here are monochrome landscapes dissolving and coagulating; and here is Novalic, carrying his image of 1918 like a window around his shoulders, striding toward us. Tamayo also uses some of the imagery Gance sketched for his later project, La Divine tragédie (1947-52), in which a Turin Shroud-like screen, carried upon a cross – floating like a sail or a wing – bears the projection of the Passion. All these images – recycled, blended, reconfigured through AI – invite us to contemplate the process of visual memory, of visual image-making. They remind us that to recollect is also to recreate, and that our relationship with “lost” films can be a generative process. The power of ruins lies in their appeal to our imagination, to invoke the spectator’s response.

This whole finale is a wonderful conceit, though I was so moved by the images of 1918 – their sharpness, their clarity, their depth – that nothing the “mind” of artificial intelligence could produce could match them. In this visual archaeology, the ruins of 1918 stand as startling outposts of a lost past – and a lost future. But how wonderful to have Gance’s project so engagingly, and so imaginatively, presented. Bravo!

Sunday 15 September 2024: Salle Lotte Eisner, 7.00pm

After a couple of hours trying to find a quiet spot to eat some bread along the Seine, I returned to the next screening – and a new venue for me: the Salle Lotte Eisner. (I will say more about the different rooms in my final post in this series.) Here I settled down to La Folie de Docteur Tube (1915) and Au secours! (1924). Two films that I had seen before but never on a big screen, and never with other people…

La Folie de Docteur Tube is usually cited as Gance’s earliest surviving film and, ironically, it was deemed too peculiar for distribution in 1915. However, it eventually accrued a reputation by its circulation on the ciné-club circuit. (Long available in various formats, the 2011 restoration by the Cinémathèque française is now available via HENRI here.) Henri Langlois famously called La Folie de Docteur Tube “the first film of the avant-garde”. The plot of this one-reel curiosity is simple: Docteur Tube (the clown Di-Go-No) discovers a magic powder that transforms himself and the world around him. He dowses his nieces (unknown; unknown) and then their suitors (unknown; Albert Dieudonné), before the group find a way to reverse the transformation.

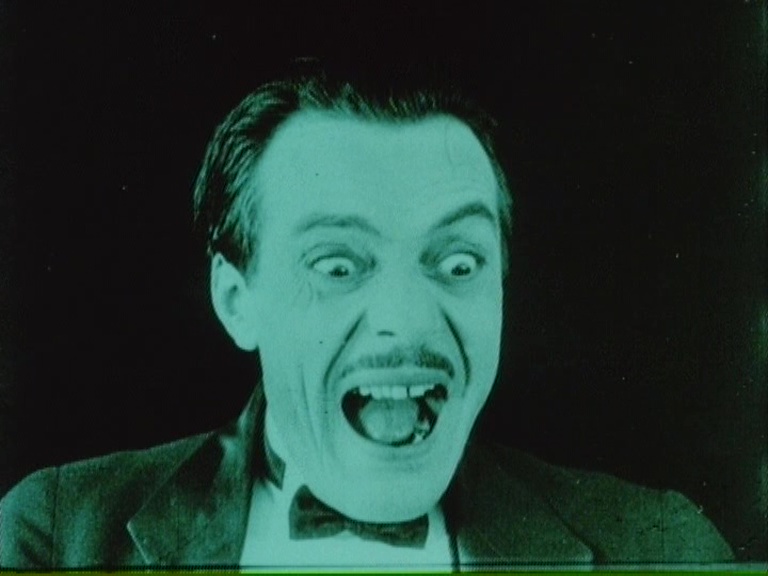

I confess that I have quite a low tolerance for this kind of film. (I find anything that might be considered “psychedelic” pretty tedious.) Even at barely fifteen minutes, La Folie de Docteur Tube often outstays its welcome. But I’m very glad to have seen it on a big screen, since the power of its imagery relies on scale. Gance achieved the transformation effect by filming scenes via a variety of distortive mirrors. Cutting from different views, seemingly from different realities, is still startling. It’s difficult to decipher these images on a small screen, and the effect is more obfuscating than revelatory. I won’t describe seeing it in the Salle Eisner as a “revelation”, but it certainly brought home the interest in Gance’s first (surviving) effort at producing truly transformative imagery. The peculiarity of the stretched, warped, distended bodies on screen force the viewer to look at the world differently. What starts off as a joke becomes an exercise in sustained visual interpretation: just what is happening on screen? There is time enough also to marvel at the effects of the monochrome smears, the blobs of black and white, the condensed creases of texture, and the sudden expansion and contraction of shapes. (I was also struck by how reminiscent these images are to the AI imagery produced in Tamayo’s Ecce Homo presentation.) I was surprised (and relieved) to find La Folie de Docteur Tube even got a few laughs, albeit slight ones. Most of these were generated by the antics of Tube’s young black servant, who mimics the doctor’s actions and delights in drinking wine from the bottle when he’s able. I find Tube’s weird grins and changes of mood quite terrifying, but his weird capering also raised a titter or two.

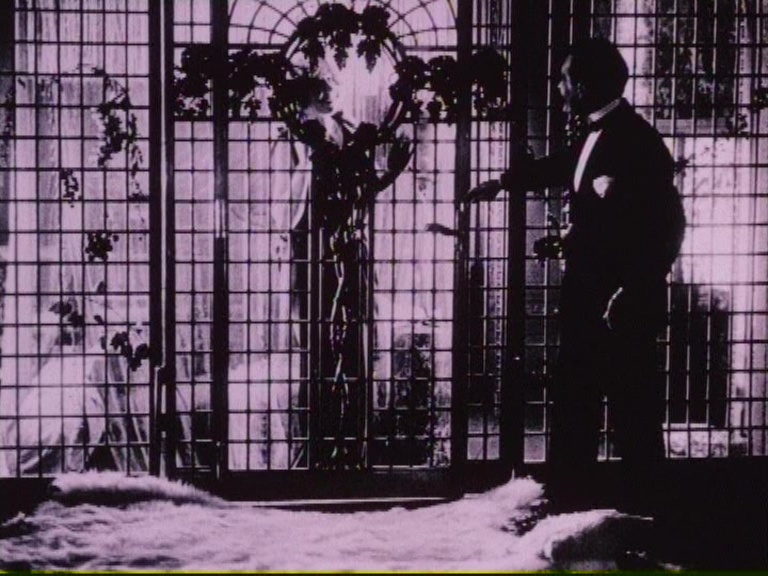

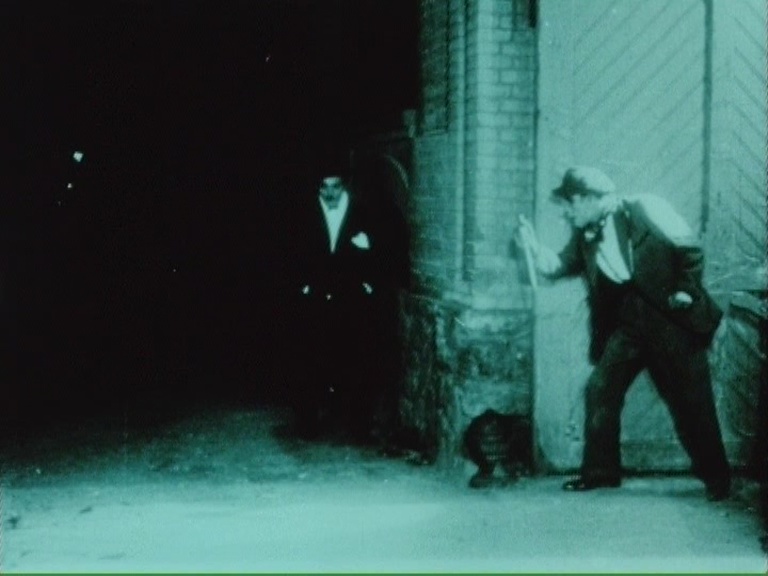

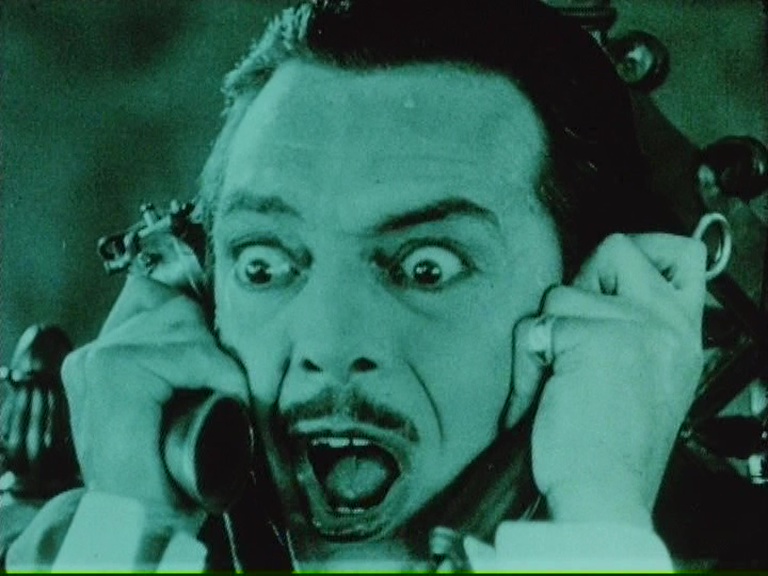

Au secours! is another film which is both very slight and incredibly elaborate. The plot involves a bet placed by the Comte de Mauléon (Jean Toulout) that Max (Max Linder) cannot stay until midnight in a haunted mansion without calling for help. Max duly arrives and is confronted by a bizarre array of walking wax statues, grizzly monsters, and hallucinatory tricks. He survives them all, but when his wife Suzanne (Gina Palerme) telephones to say that she is being attacked by a monster, Max calls for help. It transpires that it is all an elaborate hoax, on both Max and Suzanne, arranged by Mauléon.

As Elodie Tamayo pointed out in her introduction to these two films, Au secours! is a peculiarity in Gance’s filmography. Sandwiched in-between the epic dramas La Roue and Napoléon, Au secours! is a disconcertingly light film that also embodies some of Gance’s most extreme forms of visual manipulation. At various points, the screen warps – squishing and stretching Max as he swings from a chandelier – or else flickers – as a barrage of rapid montage hurls dozens of monsters at Max in the space of a few seconds. Yet these moments are soon laughed off by Max, just as the pianist (whose name I cannot find in any source: she was Korean and very good!) chose to let the flashes of montage pass in silence. Indeed, the sheer vehemence of these outbursts of avant-gardism become part of the joke. Max, the comedian, effectively laughs at the tricks of Gance, the dramatist.

Yet there is also something profoundly disturbing about this film. Firstly, the montage is very rough. Very few successive shots quite fit together, and Gance further destabilizes his film by the use of stock footage (from zoos), bizarre close-ups of stuffed animals, ludicrous apparitions, and preposterous grand-guignol. The film starts to exhibit the kind of unhinged hysteria to which its central protagonist soon succumbs. Furthermore, Max Linder’s performance may begin as charming and lightweight as any of his work of the 1910s, but ends with him in floods of tears, screaming madly down the telephone. It’s a terrifyingly convincing portrayal of emotional extremes, of a kind of madness. All these disturbing qualities are exacerbated, in hindsight, by the knowledge that Linder would convince his very young wife to commit suicide with him less than a year after the release of Au secours! (Suzanne, in the film, is also explicitly described as his new bride.) The combination of intensity, hilarity, and violence is truly unsettling. Even when the “trick” is revealed, and the count uses his winnings to pay his army of extras, our experience of the film – and of Max’s experience of events – is woefully unresolved. If it was all just theatre and props, how did the mansion warp and buckle? – from whence sprung the barrage of rapid cutting? – how can we understand the cutaways to real animals? The film only makes sense, in retrospect, if we accept that Max was subject to a sustained mental breakdown. This throwaway little film is as ultimately as disturbing as anything Gance ever made. The combination of low budget with maximal style produces (for me, at least) the same kind of skin-crawling sensation as low-budget B-movies of a later generation. The sheer awkwardness of its mise-en-scène and montage allows a kind of madness, of horror, into the fabric of the film. As much as I enjoyed seeing it on a big screen, it was also quite a relief when it was over.

Au secours! was restored in 2000 in a version that is nicely tinted throughout, and looks as good as this oddity can be expected to look. The audience in the Salle Lotte Eisner laughed along with its antics, as did I – though I can never shake off the sense of something disturbing and tragic pulling at its seams.

Sunday 15 September 2024: Salle Lotte Eisner, 8.30pm

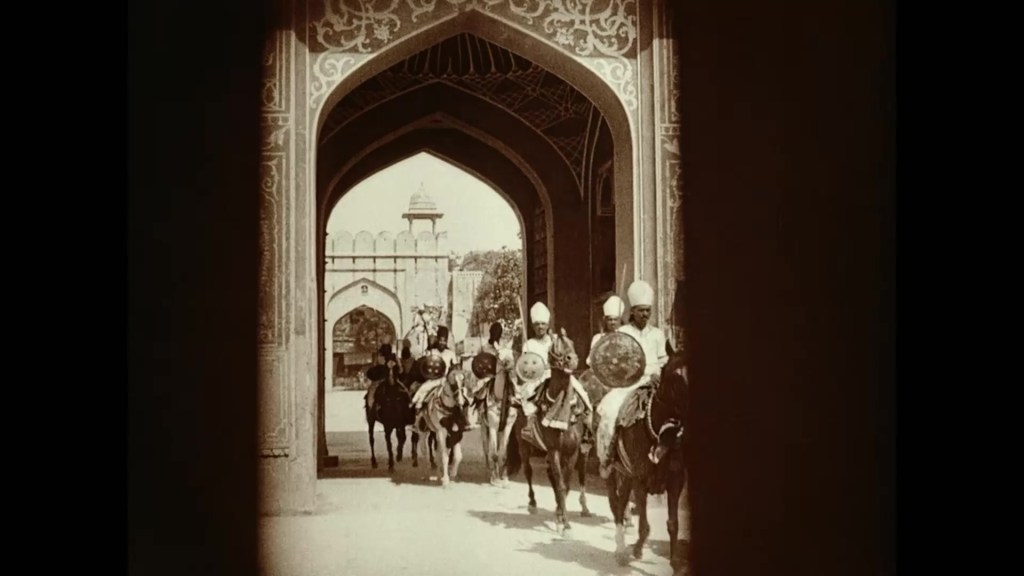

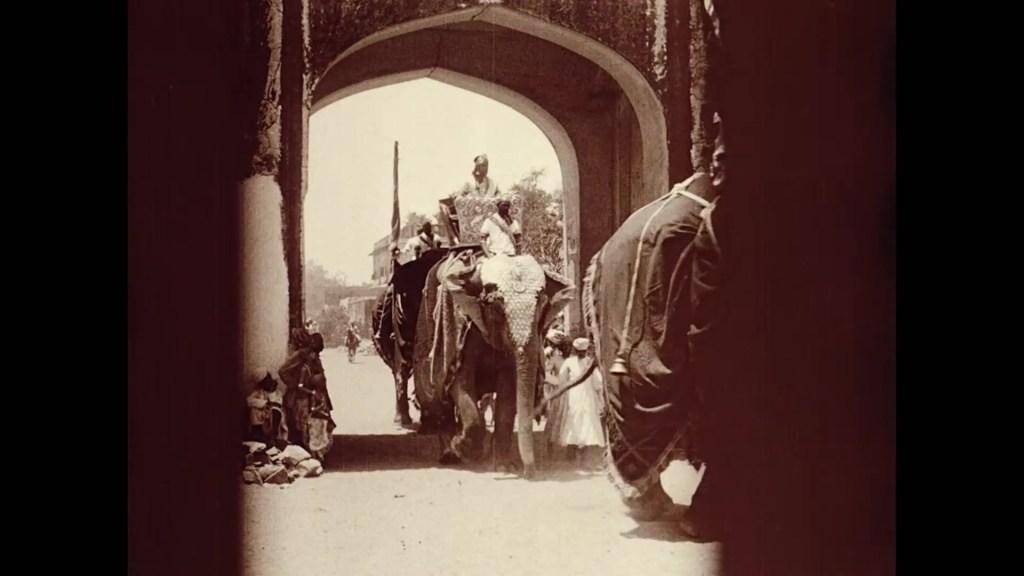

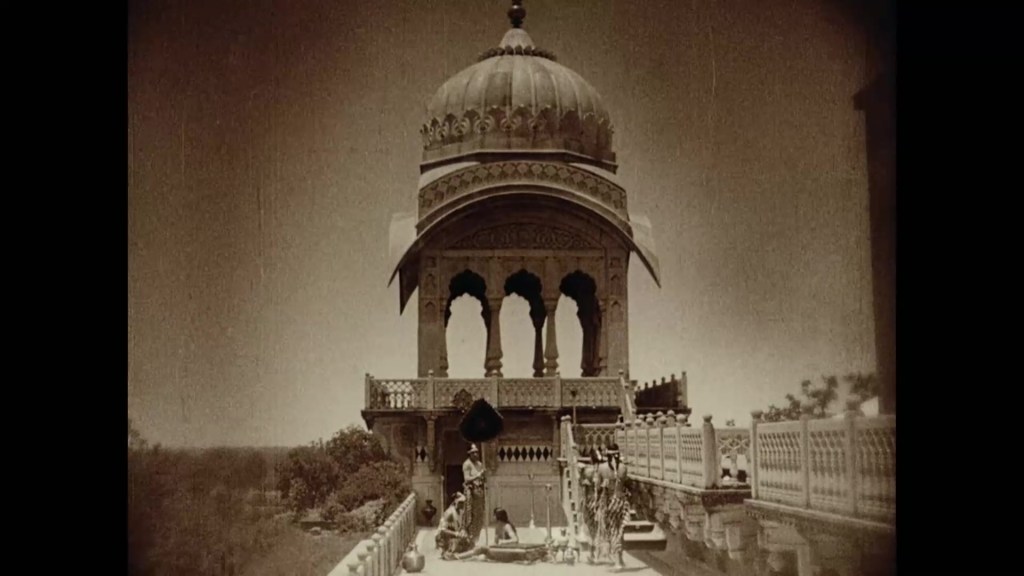

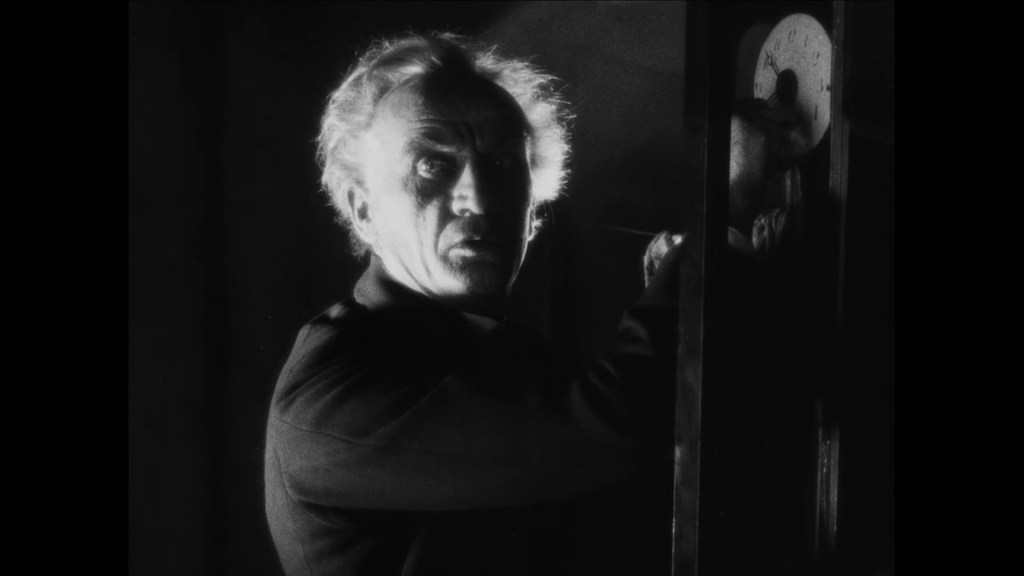

Next up was Barberousse (1917), a film I have wanted to see for years. Barberousse was first shown as an “exclusive event” with a large orchestra at the Cinéma des Nouveautés Aubert-Palace in the summer of 1916, when it was advertised as a “remarkable [film with] first-rate acting and direction” (L’Intransigeant, 11 August 1916). Yet this production was not released generally until the following spring, whereupon it became “a great adventure-drama in four parts” (Le Film, 26 March 1917) to be screened in episodes alongside Louis Feuillade’s serial Les Vampires (1915-16) (La Presse, 22 June 1917). This programming is emblematic of the market in which Gance’s film was designed to fit. The plot of Barberousse seeks both to replicate and to satirize the kind of crime serials mastered by Feuillade…

We begin with our first view of the titular figure of Barberousse (credited as being played by “?”), who wishes to become one of the world’s most revered criminals. The film then recounts his infamous murder of investigative journalists and detectives who try to discover his identity or whereabouts. Gesmus (Émile Keppens), the editor of La Grande Gazette, has made a small fortune in printing stories about this infamous bandit. Yet he can find no new reporter to follow-up these stories, since everyone is terrified of being the next victim. However, after the murder of another famous journalist (Paul Vermoyal), the writer Trively (Léon Mathot) is determined to unmask Barberousse. He allies himself with another newspaper commissioner (Henri Maillard) and tracks down Barberousse and his assistant Topney (Doriami) near their hideout on the “black pond”. But Barberousse’s gang captures Trively’s wife Odette (Germaine Pelisse), triggering a crisis of conscience for the chief bandit. Odette is allowed free, and helps her husband and the police to find Barberousse’s lair. After a gunfight and huge fire around the wood and marsh where the bandits roam, Barberousse escapes. By now, Trively is convinced that Gesmus is Barberousse. He tricks the bandit into revealing himself and Gesmus/Barberousse is arrested along with his daughter Pauline (Maud Richard). The coda to the film is another scene by the fireside of “Barberousse”, who is revealed to be a peasant who has dreamed the whole film. His family – the played by the same actors we have just seen – arrive and he sets about recounting his dream…

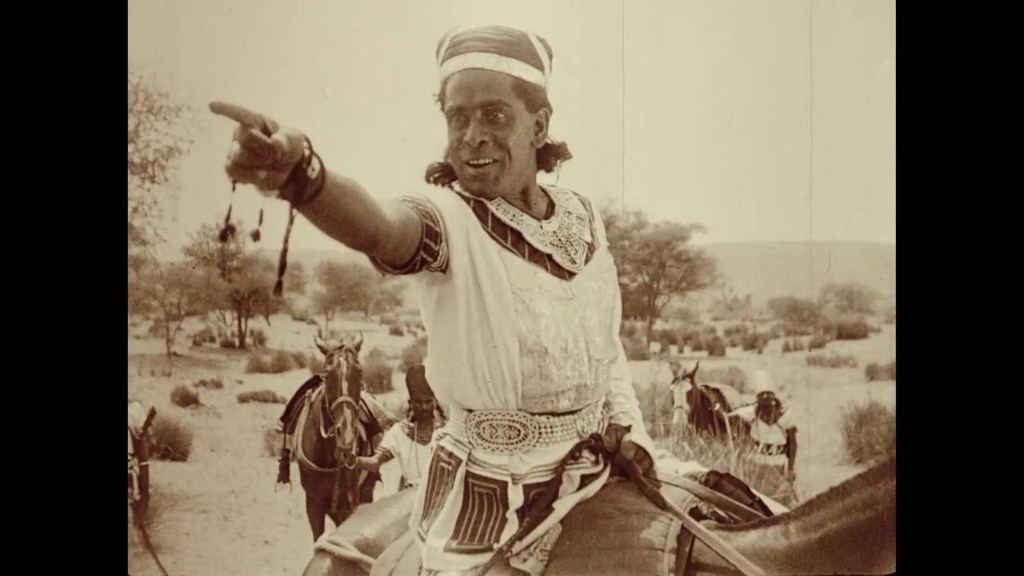

Barberousse is a delightful film: charming, amusing, and dramatic in equal measure. It is beautifully shot with some superb exterior scenes around the scrubland and coast of the south of France. Gance filmed Barberousse near Sausset-les-Pins, where he was captivated by the woodland that was blasted by the coastal winds. On screen, these woods become a mysterious lair for the bandits. The sequence in which Odette is captured by what appear to be a moving set of bushes is marvellously silly. But is also uses the wind-whipped trees of this strange landscape to produce some eerie effects. As with the other films I have rhapsodized in previous posts, I can only repeat that Burel was a genius in his own right. The lighting of both these exteriors, and many of the low-key lit interiors, is simply marvellous. The camera is more mobile than in Les Gaz mortels, and we get some striking tracking shots in cars and on boats. There is also a superb extreme close-up of Odette as she is about to drink a poisoned cup of tea: a delightful dramatic detail that, as with many others in this film, makes the contrivances of the plot come to life.

The cast is the same that appears in Les Gaz mortels, with others (like Vermoyal) from Gance’s other films made in 1916-17. Barberousse shows them all to better advantage. I much preferred Henri Maillard in this film. In Les Gaz mortels, I found him stiff and awkward. In Barberousse, he’s more assured, aided by a beard and less dramatic weight to bear. His death is delightfully silly: he’s killed by a poisoned cigar. (“Have you noticed that the smoke from your cigar has a greenish hue?” Trively asks, only to realize that the old man is dead.) Germaine Pelisse has more of a starring role in this film and manages to be convincing even when she’s being pursued by walking bushes. Émile Keppens and Léon Mathot both manage to have the right air of respective villainy and determination. Keppens, in particular, makes a splendid editor-cum-bandit-cum-dreaming peasant. Even Doriani and Vermoyal are less hammy in Barberousse than in their other Gance appearances.

This new restoration offers a rewarding and entertaining viewing experience, though there is surely some missing material. (We see only the aftermath of Trively’s first fight with Barberousse and Topney, not the fight itself. There is no explanatory text to help cover this ellipsis.) I also felt that there were some odd repetitions of frames in a few places, perhaps where intertitles were once positioned. Then again, this may simply be an accurate reproduction of errors present in the original prints. My only real reservation is the lack of tinting, which robs some scenes of their sense of temporal setting. When Topney is tapping a telephone wire, for example, he consults his notes by lighting a candle – a detail which makes no sense when the day-for-night filming offers no hint of it being dark. Blue tinting would also make the walking bushes sequences more believable, since it too is meant to take place at night. And the climactic woodland fire in the big shootout sequence would also gain much from some appropriate red or orange tinting. The oddity about this restoration is that it offers all the intertitles in blue tints – it’s just the film itself that remains in monochrome. I appreciate that without evidence it’s very difficult to try and be “creative” – but leaving the film in monochrome is itself a significant creative choice. (Having just consulted the filmography in a scholarly sourcebook on Gance, I see that Le Droit à la vie is listed as being “colorized”, i.e. tinted, something that the 2024 restoration of that film also lacks.)

I must also mention that the music for the screening of Barberousse was provided by Kellian Camus, another young talent from the piano improvisation class of Jean-François Zygel. There were some pleasing jazzy touches to his approach, and his performance matched the half-serious, half-comic tone of the film perfectly.

Though Barberousse was the last screening of my time in Paris, but I will write one further post on my experience of the retrospective and the live performances at the Cinémathèque…

Paul Cuff