It’s 1929 and Erich Pommer has just returned to Germany from Hollywood. He’s keen to introduce sound to the Ufa productions, and he has earmarked the talented Austrian director Hanns Schwarz to direct the sound musical Melodie des Herzens (1929). But first, the pair embark on Ufa’s last big silent release…

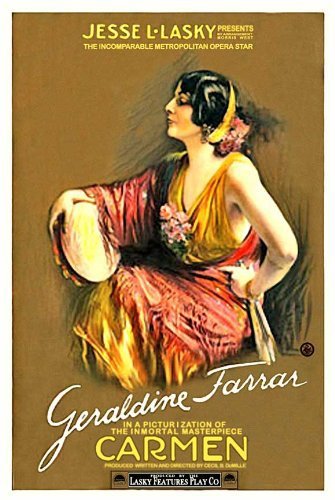

Die wunderbare Lüge der Nina Petrowna (1929; Ger.; Hanns Schwarz)

Over the opening credits, the waltz plays. Look how the music seems to match the style of the titles, their sense. The font is a little old-fashioned, elaborate. But the text manages to flow, a feeling enhanced by the way each title dissolves into the next. It’s already an elegant world, a graceful one. But it’s also sad, transient. The waltz slows, becomes a kind of elegy.

The opening shot is of a clock. It’s old fashioned. Figures of a man and woman twirl. Elsewhere, a bath is being run. The camera tracks backward and pans to reveal a series of details; we see the elaborate breakfast table, the silk sheets recently vacated, the curtained walls, the spacious reception room (and yes, I love that the camera wobbles just the smallest amount as it moves in-between rooms: it speaks of the heaviness of the equipment, the effort of moving it, the determination to complete this fabulous shot); still moving, the camera finds the inhabitant. Her back to the camera, here is Brigitte Helm. The music brings in the main theme. It’s a glorious moment.

There is a cut. We see Helm from the front. There is a rose at her lips. She looks dreamy. She is dreaming, a daydream of someone we have yet to meet. When she looks to her left, we see her in profile. Is it my imagination, or is Helm even more beautiful than usual? She looks vulnerable in a way I’ve not seen before. I associate her with those pencil-thin eyebrows, raised in determined desire. Fritz Lang made her a star in Metropolis, but that film is such an oddity, filled with cold formality, with exaggerated tableaux and exaggerated performances—and all exacerbated by the faster-than-life framerate (seemingly in accord with its makers’ intentions)—that it’s difficult to get over, to get past. Even in some of Pabst’s films, Helm can relapse into a kind of archness that is very pleasing and striking on screen, but doesn’t always engage you in a complex, emotional way. But here, in Nina Petrowna, from this very first moment, it’s like she’s a different person, a different presence on screen. And it’s a private moment, this scene of her on the balcony. She’s not putting on a show for someone, or for the camera. The music dies away. Nina looks up.

The cavalry is on parade. The orchestra strikes up a march. But look at how Schwarz frames this scene. The horses and men are behind a high, dark, imposing fence. Who is being held off from whom? (As the narrative unfolds, we realize that both our lead characters are limited by the roles this society gives them: the confines of army life are as imprisoning as the confines of Nina’s apartment.)

On the balcony, Nina appears curious, but only mildly so. For she turns away to walk back inside—only, she cannot. Her silk throw is caught upon the balcony rail. She turns round and struggles to free it. The parade continues below. And now she looks more carefully at the men. Look at the way her face changes. She breaks into a kind of smile. But again, it’s a private smile. She’s not smiling for someone, but for herself. There is a vulnerability here. A delicious touch of backlighting haloes her uncombed hair. She throws the rose at one of the cavalrymen. It lands in his lap; surprised, he looks up and sees Nina. In each of their faces, we see a kind of childish delight. His wide-eyed surprise becomes a boyish grin. Her smile is almost a giggle, and the way she raises her hands up to her face is so gauche, it’s the gesture of a much younger girl. As if to underscore the innocence, Schwarz cuts from these close-ups to a wider shot of the parade disappearing round the corner—all overlooked up a stone cherub, who looks like he’s reaching out to touch one of the men. It’s an arresting image, sweet and sad. Sweet, because it’s an image of innocence; sad, because the men are out of reach—and because the glitter of armour makes them impregnable, cold, brittle. (Sad, also, because I’ve seen this film before, and I know what it all means.)

Nina shakes her head a little and goes back inside. Cue: the man of the house. A rich man, from the cut of his tunic; an important man, from the emblems on his shoulders; a wealthy man, from the way he is so at ease in the luxurious apartment, from the way he strides up the staircase. He has instant access to the inner rooms, to Nina’s hand, offered to his lips from the privacy of the bathroom. (His name is Colonel Beranoff, but the film purposefully denies us this for the moment.)

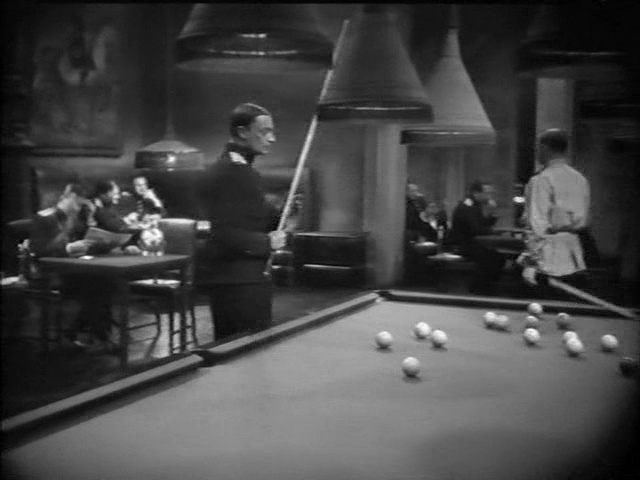

In the off-duty rooms of the barracks, we see the cavalrymen at ease. But the music tells us this is a military space: snare drum, marching rhythm, brass footsteps. The cavalryman we recognize from the parade is introduced—but not by name (more on this, later). He is merely “this young’un”, newly arrived in St Petersburg. His comrades (all moustached, unlike the cleanshaven youth) will show him the town. They take him to a nightclub.

The night club. Schwarz begins with a shot of fish in a shallow pond. It’s a curious image to begin the scene. It’s another image of entrapment, the fish behind their glass wall. The camera tracks back to reveal the luxury around them. The music is elegant, easy; another waltz, softer, sadder. The soldiers enter. The elder men show their innocent comrade the ropes. He kisses the hand of a woman, who seems to have been waiting for soldierly company. But as he lifts his head from her hand, his eyes catch sight of movement above him. In a balcony overlooking the hall, Nina and her companions are settling down. The cadet is all wide-eyed surprise again and, as in his first sight of Nina, breaks into a boyish smile. He is caught by surprise, by desire—by a desire not sought, but happened upon. (His comrades knew they’d find company; he was not looking for Nina.) His comrades look up to see who he’s seen. A fabulous shot through the jets of water from the fountain: the images is neatly divided so that we see distinct the two balconies, one with Nina, the other with a stranger. And oddly it’s the stranger who gives a Brigitte Helm-like look of desire back down at the soldiers (the raised eyebrow, the narrowed eyes; it really is very “Helm”). The soldiers mistake her as the object of their friend’s look. And it’s now that they name him: Michael Andrejewitsch. It’s one of only two times that he’s named in the film, and this first time is in the context of mistaken identity and desire.

Michael orders a rose, which he now holds to his lips—just as Nina spots him. The high/low spatial dynamic of their initial encounter is recreated: Nina again on a balcony, Michael below. But this time Nina is not alone. Her look of desire is seen by the man next to her: her lover, Colonel Beranoff. It’s a revealing shot: for it shows us the source for Nina’s (literally and metaphorically) “high” position. It’s not her table, it’s Beranoff’s; it wasn’t her apartment balcony, either: it was his. It’s another sad moment. And look how the two people falling in love are framed: she overlooked by the man who effectively owns her, he overlooked by the fountain, framed by water, looking small and vulnerable and out of his depth (socially, yes; romantically, yes; and, most certainly, financially).

And, oh goodness, yes, please look at Helm’s face in this scene. She starts to convey her desire—less girlish than in that first encounter; it’s more of the look we associate with Helm from other films: the eyebrows, the tilt of the head. But no sooner as she expressed this look—a look of desire, certainly; but, more than that, a look of agency, of will—than she relinquishes it. It’s a beautiful moment of performance. Just see how that clear sense of wanting drains from her face. It’s not that she ceases to desire Michael, but that she realizes that the man sat next to her will not allow it. She cannot express her longing, for her longing is prescribed. So she immediately adopts her casual, disinterested persona for Beranoff—you can see her shake off her self and become another. “Is he a good friend of yours?” the colonel asks, nodding down to the tiny figure below. Oh, just a childhood friend, she says—she lies. (As I rewatch this scene, I’m almost convinced Helm is speaking in English. It would make sense, as she’s speaking to the English actor Warwick Ward. How interesting that this first “lie” is itself spoken, albeit silently on screen, in a second tongue.) Nina is performing, and Beranoff knows it. Ward’s performance is excellent: so knowing, so charmed in his lover, yet so unbelieving. “A charming lie”, he says. “Are you jealous?” No, he isn’t—and to prove it, he invites the cadet up to their private room. (There are two other men at their table, but the camera and Nina hardly concern themselves with their presence. Nina is worried what’s happening down below.)

The exchange between them is overlooked by the colonel. He’s almost amused—almost. But he leans against the wall, casting a shadow—occupying space. He doesn’t have to say anything for his presence to be felt. And look at Helm’s face: hiding her emotion from Beranoff, resenting his presence, and falling for Michael. They waltz, and the camera moves. The piano is being played on screen, and all that’s left in the theatre is the piano below the screen. One of the colonel’s companions turns off the light. It’s ostensibly to make the effect of the punch flambee more noticeable, but it has the effect of giving the illusion (only the illusion) of intimacy in the room. Nina and Michael are in silhouette against the balcony; Beranoff becomes a dark shadow against the wall. (The scene also presages the electricity going off in the lovers’ flat, later in the film.)

The colonel quickly tires of their dance and turns on the light: the waltz ends. The young couple looks embarrassed. Nina’s face falls: once more she must hide her feelings, play the game. She dons her fur coat; she looks extraordinary. We see Michael’s eyes on her, then they fall away to the floor. What is he thinking? Well, we surely know: it’s like her downcast eyes just now, it’s the feeling of desire creeping up on him, and the sadness of unfulfillment. But Nina gives him a knowing look. Their farewell is brief. We don’t see what’s happened, initially, for Schwarz cuts to a close-up of Michael. It’s another marvellous little moment, this look on his face—and Francis Lederer’s performance is pitch-perfect. It’s innocence and expectation mingled, longing and trepidation at the same time. The camera follows his eyes as he looks down: Nina has placed a key in his hand. (And oh, the music—it’s just perfect. The waltz ebbs and flows below the image, romantic and melancholy. It’s drifting above the image, sympathetic but distanced, knowing but detached.)

This same mood is carried into the next scene, when Michael havers outside Nina’s villa before using the key to enter. The music here is cautious, almost anxious. Michael’s entry is the opposite of Beranoff’s: the colonel swept upstairs, but Michael hesitates at every step.

And here is Nina, opening the door. She, too, is half knowing, half hesitant. She knows what they both want but is not sure the hows and wherefores—and what it might mean. Michael is all boyish hesitancy. Nina offers him a seat, a closer seat. Why not sit next to her? She goes to him.

“You must have wondered about my strange invitation—” she says. He coyly shakes his head, grinning like a child whose smugness gets the better of him. Cut to Nina, whose smile fades, slowly, who looks away. This is a perfect scene, a perfect performance. You know everything about Nina’s life in the way her smile fades, right here. You know that she likes Michael, that she desires him physically, but that she hoped for more than just physical love. And the look on Michael’s face—that suggests he is not as innocent as he seems, that he assumes she is a certain kind of woman—hurts her. She worries that he thinks he has won the right to her body, that she is no more than a body to him. And the slowness of this realization, the way it imbues first the close-up of her face, then the shot of them sat together, says so much about her life. Surely now we understand her relations with the colonel, which is more of a transaction than a relationship? Surely we can fill in the blanks of how she has had to get by until now. We have not seen her in the company of friends, only the colonel’s friends. Does she have friends? What has happened to her family? The fading smile here, it seems to me, is a very lonely thing indeed. She thought she might have been connecting to someone, only for this connection to be another transaction. (It was this moment that made me fall in love with the film. Suddenly, a whole stratum of feeling is revealed beneath the surface.)

“I think it’s better if you were to leave”, she says. Now it’s Michael’s turn to realize what’s going on, how much his little grin and his little shake of the head has hurt her, wronged her. They shake hands, and as they touch the clock chimes. The montage of the clock from the opening scene begins again, and the film changes once more. Nina moves close to Michael, and they dance to the music of the clock. What are we to make of this? It’s a delightful scene, but it’s something else. Schwarz cuts from the clockwork man and woman twirling to the dance of the human couple. Is Nina simply fulfilling Michael’s expectations? Does she lead her life with a kind of mechanical drive, an ingrained habit?

“Actually, you could spend the night here”, she tells him. She goes for champagne (seeing and hiding a picture of Beranoff en route); they drain their glasses; he refills the glasses and she looks at him. The music moves from tension to something tender. Nina lies back on the bed. She’s putting on a seductive face (more Helm-like). Michael looks at her. “You must be very tired, Madame— —?” (That double extended hyphen is a lovely touch in the original title. I love a good hyphen, it’s so gestural.) The question makes Nina cease her seductive performance and sit up. She agrees it’s bedtime. He makes to leave, and we see Nina shake her head. Is he so innocent? She makes excuses about him not being about to leave: what would the neighbours say? The villa is large. She leads him by the hand to the next room. Michael looks around, in wonder. It’s clearly the nicest bedroom he’s ever been in. Nina says goodnight and leaves. But she goes only to the other side of the door. Each one listens to the other through the door, hesitant. Nina stands. The clock ticks. She quietly opens the door. Michael is asleep in a chair. He hadn’t dared even go into the bed. She looks at him sleep, almost shaking her head.

The camera finds them the next morning. She has slept on the floor by the door, and he finds her there. They are suddenly both children, innocently waking and then picnicking their breakfast on the floor.

Beranoff walks in. The colonel makes the immediate assumption that Nina has slept with Michael. “I hope, officer, that you are as pleased with her as I’ve been!” he says. (Incidentally, Michael is addressed by his rank of “Kornett”, the lowest rank of commissioned officer in the cavalry. He is, technically, an officer—but only just.) He leads Michael out, warning him that “Women and officers should have only one master!” It’s a line that reveals just what he thinks of Nina, and women in general. Beranoff next shouts at Nina, asking her to invent some new lie to explain herself. So she tells him that she cannot lie, since she loves Michael—and says he spent the whole night with her, sleeping apart. The colonel laughs and applauds her “lie”. Just as Michael made assumptions, so does Beranoff. He offers Nina the chance to leave, but she must also leave “his” diamonds, “his” furs. The full extent of her position, her lack of power, is revealed.

Michael, meanwhile, is caught by a superior officer coming back to the barracks late. “Women, no doubt the reason for your being late, are worth nothing”, the officer explains.

Nina arrives at the barracks, and of course Michael gets into her carriage. There is a long, long moment as they say nothing—until she puts her hand in his. She takes him to her apartment—her apartment. It is bare, dark, small. Michael looks around him. “You live here now, Nina Petrowna?” It’s the first time anyone in the film has spoken her name, and it comes now—when Michael realizes what she has given up, and what kind of life she has led until now. You can see him realizing it on his face. He looks adult, for once, and when he smiles it’s out of respect—an adult emotion. They kiss, and there is a propulsion to their embrace. It’s like an obstacle has been overcome, they are ready for one another.

They are living together. Nina is peeling spuds. There is clock on the wall, a simpler clock: instead of the elaborate mechanics, a small bird pops out to call the hour. There is no wine, they don’t have enough money. But Nina lays the table and looks truly happy. And Michael can afford to buy only one flower to bring home for her; but he looks happy. Nina plays their waltz. It’s a lovely scene, for the orchestra in the theatre must stop and wait: the solo piano takes over and mimics the attempts of Michael to learn the tune on screen. It’s lovely, too, for the way it’s played. The lovers are still having fun, enjoying being next to one another, giggling, joshing. Their bodies are in synch. Michael wears his uniform in a casual way (you sense he’s wearing the hardy coat for warmth in a cold apartment) and Nina’s hair is loose. So there’s a touch of studentish-ness about them, a little shambly, a little boisterous. Nina is called to the door. The orchestra resumes its accompaniment, only for the piano to try—and fail—to play with it, as Michael fluffs his playing.

Nina must lie again, a well-intentioned lie. For the electricity is about to be cut off, and she can’t bear to tell Michael how much money is owed. The lights go off as Michael fumbles with the piano. The scene harks back to their first dance in the dark. There, the piano waltz was stopped by the lights going on; here, it’s stopped by the lights going off. Nina pretends the outage is for Michael’s sake: a surprise dinner with candles. “Isn’t it beautiful?” They kiss, and Michael accidentally breaks her bracelet. Wanting more light, he goes to the switch and the truth is out. There is a long close-up of Michael, realizing what’s happening. Nina looks at him (another tender, sad close-up of Helm) and Michael promises to make enough money once he’s promoted. He sees her battered shoes, and the scene ends with his eyes in thought and hers looking away in contentment as she strokes her hair.

The officers’ casino. Michael joins a table. His face is boyish enthusiasm, excitement. Beranoff comes over, sits. Drinks are poured. The night goes on, turns to morning. It’s a scene out of Joseph Roth: the young officer trying to keep up with his peers, being out-played and out-drunk. So Michael cheats, and Beranoff sees him. Beranoff makes to leave. He puts on a fabulous coat, a fabulous hat. His status is on show (immaculate frockcoat, medals, buttons, aiguillette, sabre), as is Michael’s low rank (simple tunic, unembellished). He confronts Michael with a pre-written question that he only has to sign. It’s the first time we see Michael’s simplified name: M. Rostof. He has signed his own suicide note, for this is “the only solution possible for an officer”. But Beranoff makes him an offer: report to his flat tonight…

Cut to Nina, joyfully expecting Michael’s return. The phone rings, and Beranoff makes an unspecified threat about Michael’s career. So Nina arrives chez Beranoff. She is cold, dignified. But she tries to hide her shoes from Beranoff’s gaze. But in every scene with Nina, we know Beranoff to be knowing, shrewd, observant. He plays his hand perfectly: shows Nina the confession, the card. She looks at him harshly, but then goes to the window and cannot hide her tears. So Nina makes the deal Beranoff has forced her to make: she will save Michael by giving him up, and report back to the villa. When Michael comes in, Nina has left, and he accepts Beranoff’s apparent change of heart with that same, boyish expression that he had when he thinks luck is on his side. And on his way home, he goes into a shoe shop.

We know what will happen next, but it’s still hard to watch. Nina is alone. Their plates have already been laid out on the table. She has decorated Michael’s with sprigs of flowers. She strokes his empty chair. She extinguishes the candles. Now she must lie again. But first Michael presents her with a gift. The look on Nina’s face—wiping away tears when Michael cannot see… She unwraps the box. Look at her face, her hands—she is so happy. And Michael too grins with satisfaction. She cradles the shoes, strokes them; but her face hardens. She swallows. The music slows, turns to a minor key. “It’s very nice of you, Michael, that you’ve bought me a pair of shoes…” (and we see her face again; her eyebrows arching, something like forced cruelty taking hold of her—a performance taking shape) “…but do you think that I would wear such common shoes?” She stands, chucks the shoes onto the chair, and walks away. It’s such a devastating moment, to watch her break his heart—and to know that hers is already broken. There is a close-up of Michael, clearly hurt, clearly very hurt—hurt in such a way that he can hardly move; it’s all in the eyes, the slightly open mouth, not knowing what to say. “That’s not all Michael!” Nina adds, spinning round. And her face is almost disbelieving, almost surprised at her own performance. “I must finally be honest with you. I’m tired of living in this poverty.” Her arms swing, she arches her back. Michael comes over. “I need the wealth, the splendour, the villa…” It would be too easy to feel more for Michael in this scene, were it not for what he does next: he shoves Nina, shakes her against the cabinet. It’s the act of a child, not a man. It shows how immature he is. It tempers our sympathy with him and switches the emotional focus of the film back onto Nina. This is her film, after all. And it’s her performance here, in this scene, that we realize the “wonderful lie” she’s telling. You can tell how much it’s taking out of her: she’s almost lopsided, leaning on the sideboard for support while lurching her shoulders forward and throwing back her head. She says she’ll sell off everything she’s given him—she means Michael to think this refers only to her body, but we know it’s far more than that. Michael rushes out, and Nina is left at the shut door, leaning against it to keep her from collapsing. Cut to the cheap clock on the wall, with its little bird emerging to cry the hour.

And Schwarz dissolves from this clock to the clock we recognize from the opening shot of the film. If the clock seemed charming or silly when it first appeared, it now feels tragic. For the image has now attained its true significance, its full weight of meaning. We know the clock belongs to Beranoff more than to Nina: it is Beranoff who has determined the rhythm of Nina’s days, the timeframe of her life. The mechanical lovers are condemned to repeat their dance, which can never alter. Time is prescribed, movement is predetermined. So we see the mechanical couple waltzing once more, and the camera once more tracks back across the villa’s interior space to find Nina at the balcony, once again with a rose in her hand. Snow lines the streets. Here comes the cavalry. She looks for Michael, finds him, throws the rose. He ignores it, ignores her. We see the cherub, once more reaching out for the receding column of men. Nina turns, slowly, almost limping back inside.

The image of the discarded rose, lying on the snow, dissolves onto a huge bunch of fresh roses—and the camera tracks back to reveal them in Beranoff’s hand. He runs upstairs, bursts into Nina’s room and sees her lying on the couch. He’s all smiles. He throws the roses one by one over Nina—and now his face changes. There is a close-up of Nina, eyes closed. In the score, the solo violin was playing over a few sparse, pizzicato chords in the strings; now the music simply stops. Beranoff sees the empty vial on the floor. He drops the roses. The camera moves up from the vial on the floor, up along the line of Nina’s hand and arm, drooping from the couch, up to her face, then tracks left along the line of her body; we realize she is wearing black, and the roses strewn over her unwittingly fulfil the funerary rites. The camera still moves along her body, as the orchestra resumes its course—playing now a slow, funereal march. The camera reaches Nina’s feet and stops: she is wearing the shoes that Michael gave her. A slow, slow fade to black. ENDE.

I was very taken by this film the first time I saw it, and rewatching it has reinforced my appreciation. Most of all, I admire the performances. Francis Lederer gets his role as the young officer just right: it’s a perfect rendering of someone of that age, of that rank. He’s keen but gauche, clumsy but tender, greedy but shy. The performance could easily be silly, exceeding in any one of the conflicting emotions; but Lederer keeps everything in check, nothing is overdone. Warwick Ward plays the colonel with every bit of charm, superiority, and knowingness the character demands. He never has to emote, to shout or scream: the point of such a figure, of a man of this rank and wealth, is that he never has to emote or shout or scream to get what he wants.

And of course, there’s Brigitte Helm. I never thought I’d be moved like this by her on screen. Fascinated, yes. Enticed, yes. Delighted, enthralled, yes. But really moved, no. This film shows Helm at her most subtle, most empathetic. Of all the films of hers that I have seen, this is her most nuanced performance—aided by the superb direction. Those early scenes with Michael in the club and then in Nina’s apartment are so, so touching. It’s almost like we watch the star persona (her “role” as kept woman) fall away to reveal the young woman beneath. Several of the contemporary reviews I’ve read compare her unfavourably to Greta Garbo. It’s true that Nina is a role Garbo would have taken had the screenplay been realized in Hollywood. But I’m glad it wasn’t, and I don’t think (as some German critics did) it does Helm discredit to take it on. Though Garbo was only a few months older than Helm, somehow I can’t quite think of Garbo being the child-like host of Michael for their picnic in her apartment. Rather, I can’t imagine being surprised by the transformation in the way that I was with Helm. It’s a subtle, sophisticated performance, by turns fierce and vulnerable.

Of course, the whole film looks stunning. The sets are gorgeous, the costumes exquisite. It’s a rich, complete world on screen. Nina’s apartment, the nightclub, the barracks, and the snowy streets outside are all coherent spaces, each suggesting their own context and history. And the way the camera glides through these spaces, or glances from one space into another, is fluent, expressive, articulate, meaningful. The cameraman was Carl Hoffmann, one of the great names of German filmmaking in the 1920s and beyond. If he had shot nothing else, Hoffmann would be renowned for being the chief cameraman on E.A Dupont’s Varieté (1925) and Murnau’s Faust (1926) (to say nothing of his earlier work with Fritz Lang). If Nina Petrowna does not have the spectacle or scale of these earlier films, its images are nevertheless as stylish and delicious as anyone could want. I particularly love the dark limits of the film’s frame, the way the iris gently shapes the images. It’s most visible in the darker interior scenes, further excluding everything beyond the frame from our eyes. The outside world seems less interesting. And I’m more than happy to forget what’s beyond the screen, the scene, the performers. (Most especially, that first time they dance, or their first night together.)

In all this, it might be easy to forget the director: Hanns Schwarz. Lots of reviewers dismissed him as a merely superficial, decorative director. But it’s unfair to think the film would work merely by dint of its sets or camera movement, as if the performances fall into place without someone human directing them. So, yes, I credit the film’s success to the guiding power of Schwarz. And although the story might be a variation on a familiar theme from literature or cinema, it’s still moving and well realized. I wouldn’t argue that the film is “great” in the sense that other films of the late 20s are great. It’s not setting out to change the world or revolutionize camerawork and editing. It’s not what it sets out to do, but how it does it that makes it great. I can’t imagine it being done better.

Saying how good the film looks, I should say (as my images suggest) that I was watching Nina Petrowna via a version broadcast on Swiss television many years ago. On a smallish screen, it looks fine—and certainly shows how good it should look. (I also have a friend who saw the film on 35mm when it was shown in London in 1999-2000, who confirms that it does indeed look superb on the big screen.) A newer restoration of the film was completed in 2014-15, which is listed as being slightly longer than the version I’ve seen. (Although this always depends on the framerate of either version.) To finish, I can at least show one frame from the new restoration. Interestingly, you can see more information in the frame from the broadcast copy: the still from the DCP has slightly cropped the image to lose the rounded corners of the original aperture. Shame. Give me my rounded corners! Give me more Nina Petrowna!

One of the other great pleasures of the broadcast copy I saw is the original orchestral score by Maurice Jaubert. The soundtrack was recorded in 2000 for its broadcast on ARTE, Dominique Rouits conducting the Orchestre de Massy. Interestingly, the Jaubert score was not the one performed in cinemas for its Berlin premiere in 1929. There, the score was by Willy Schmidt-Gentner—and contemporary reviews all say how wonderful it was. I’m curious to know if it survives, but the Jaubert score is so good that the film can thrive without the “premiere” music. This was Jaubert’s first film score, and his only one for silent film. It’s built around a few melodic themes, all of which are instantly memorable and which vary and develop over the course of the film. It’s wonderful the way it wrings so much out of a simple set of melodies, by the way it changes instrumentation—moving from the full orchestral sound to smaller groups of strings, and even down to solo piano. Like so many scores of the period, it doesn’t try to hug the images too close: the music drifts over the film, creating mood, filling out the emotional resonance of the scenes. I catch myself humming bits of it very often. I hope a new recording is made for the new restoration—and that the film gets a proper release on Blu-ray someday. It’s very much worth it.

Paul Cuff