Day 7 brings us the film I was most looking forward to seeing among this year’s streamed content. (Pause to consider what a foul phrase is “streamed content”.) It’s also the film that most conflicted, confounded, and confused me.

Manolescu (1929; Ger.; V. Tourjansky)

Manolescu and Cleo con their way through European cities, stealing and defrauding as they go, on the run from the law and her ex. Will she escape him? Will he escape his own lifestyle?

I have great difficulty in writing about my feelings for this film. For a start, I made no notes when watching it: Manolescu was the one film I wanted to concentrate on entirely, without pen or paper to distract my eyes even for a moment. To write this review, I’ve had to go through the film again and my thoughts are even more complex now that I see again how rich is the look and feel and design of the film. But my reservations are still there. So here we go—with due warning of sexual violence in the content…

Paris. Smouldering nightscape. A descending camera over the rooftops. A homeless man on a bench. Nightclubs ejecting revellers in the early hours. Mosjoukine as Manolescu in his finest night attire.

But Manolescu is back home and exercising by 7 a.m. The curtain is drawn. Outside, a studio Paris so fabulous the camera can drive elaborate routes through its impeccable geography. Here are cars and people, dark streets, neon signs.

A letter from the Club: Manolescu owes them 82,000F. Paris rejects him, so he obeys the neon suggestion outside: “Adieu Paris / Visitez Monte Carlo!”

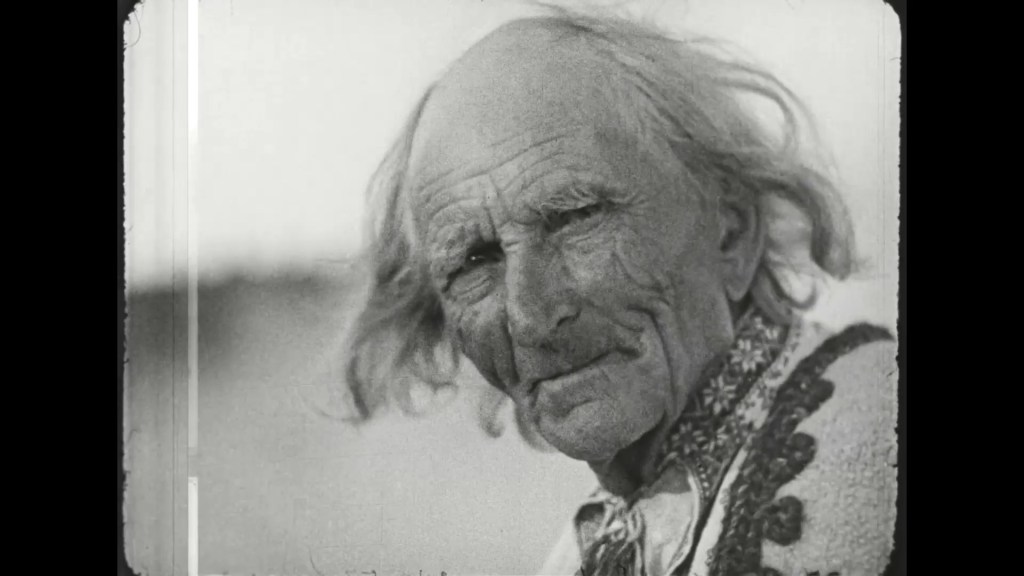

The station. Steam and smoke. And Brigette Helm, smoking and sultry. She is Cleo and Manolescu stares at her and takes the neighbouring compartment.

Jack arrives to say farewell to Cleo but is being observed. His agent warns him off. He leaps onto the train, but then leaps onto another train in the other direction. The police board the train to Monte Carlo and inspect passports.

Manolescu tries to get into Cleo’s room, first by stealth then by force. The police arrive and Cleo realizes she needs protection, so she pretends to be asleep in Manolescu’s room. The police go. He locks the door, then the door to Cleo’s apartment. He paws her, forces her back onto the bed. She pushes her back against the compartment wall, closes her eyes, waits to submit. It’s a horrifying scene.

Now there are astonishing landscapes. Glorious sun and shade. Gleaming cliffs. Gleaming hotel facades.

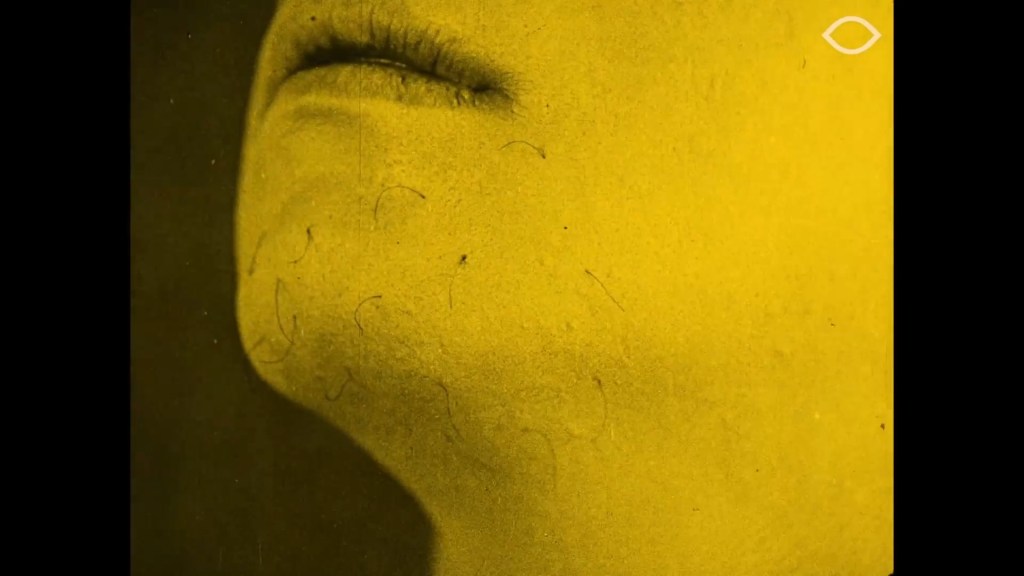

Cleo has given Manolescu the slip and gone to her hotel. Manolescu follows. At reception, he pretends to be “Count Lahovary” to get better service. He cons his way into Cleo’s room. She’s in the bath. She demands he leave, again and again. He waits outside. She dresses. She confronts him. Eye to eye. The most astonishing shot, held for a long time: her eye the focus of the whole world, staring at him in a kind of wilful fury. His face. Gleaming eyes. A smile fades. “What do you want from me?” His answer: he grabs her, kisses her breast. They writhe together. She reacts with hatred. The camera tracks closer. They stare at each other like animals. They kiss, his hands around her throat.

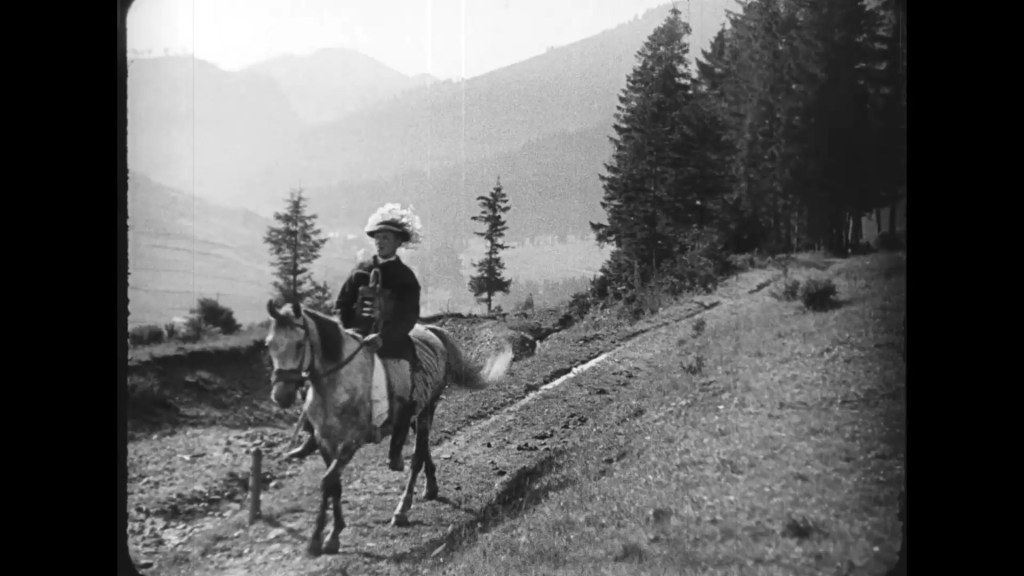

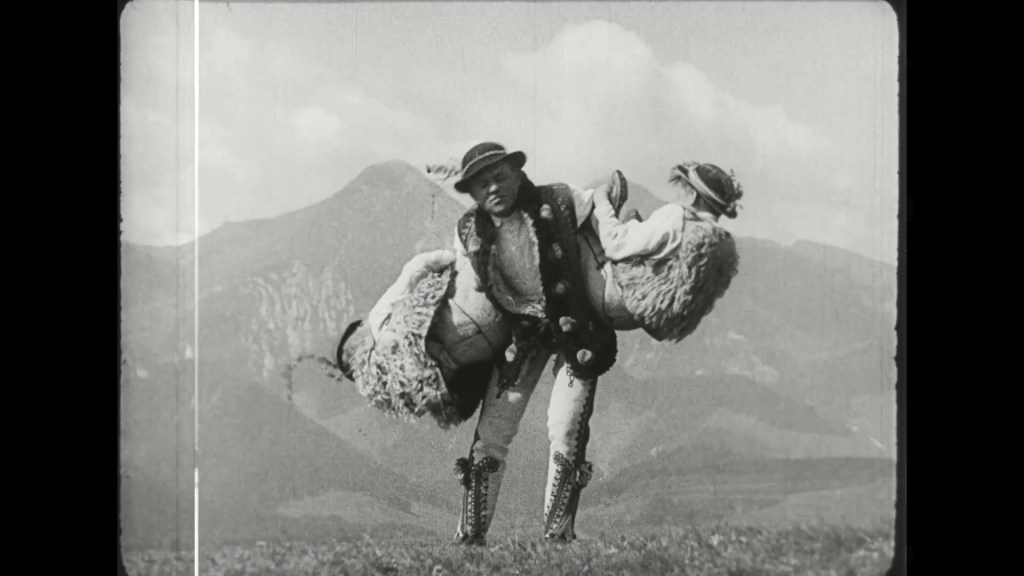

They are together, laughing, running, exercising in the sun, riding, boating. Their embrace amid the sheets. The camera begins to spin. Their whirling faces dissolve onto the gleaming whirl of a roulette wheel. Casino life.

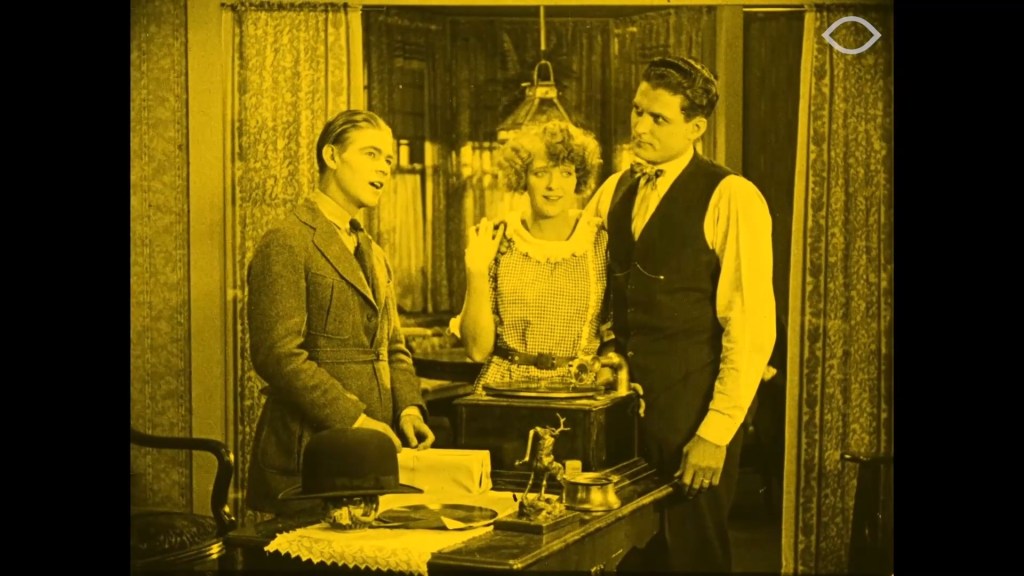

At the hotel, Jack arrives with a huge bunch of flowers. He’s like a bear. His hair in grizzly flight from his enormous head. His moustache a black lightning bolt under his nose. He enters. Manolescu hides on the balcony at Cleo’s instruction. Jack and Cleo. Their embrace turns into a kind of fight. She wrests herself away, giddy. Hatred disguised as decorum. Fear and panic. Pretence. (On the balcony, Manolescu peers into the neighbouring room: a rich old woman storing her jewels. An idea.) Jack leaves to dress. Cleo and Manolescu. What is she thinking? (Really, what is she thinking?) They kiss. There’s something animal in them. Jack walks in. There is a fight of amazing savagery: punches hurled in close-up, fury in the eyes, fury in the bodies. More animalism. Cleo flees, but only into the corridor to get help. The police arrive and drag Jack away.

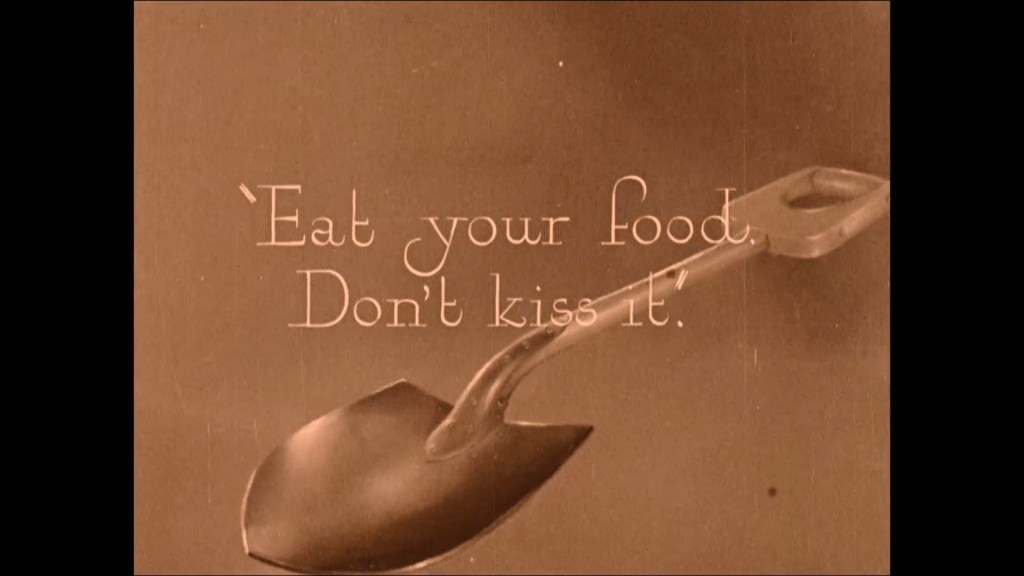

Manolescu promises they’ll stay together. “We stay together?” she replies. “Could you then offer me the life I am used to living?” Taken out of context, it’s an extraordinarily revealing question. The life she’s been living has been one of enforced companionship and criminality. (And sure, he’ll give her that.) But what the question is taken to mean in the scene is one of finances: could Manolescu provide her with enough money to live the way she wants. So he steals the rich woman’s jewels in the neighbouring room.

Title: “That’s how George Manolescu’s life as a swindler began.” (Really? Wasn’t he already fleeing debts in Paris? Isn’t he already a rapist?)

Their life of crime and money fraud. Manolescu cheats his contacts and wins out.

Jack in his cell, his agent promising him to help with Cleo.

London. Neon signs. Pearl theft. Shots of faraway places. Newspaper headlines across the world: Manolescu’s thousand disguises, thousand crimes.

A nightclub. Cleo staring at another man. (No-one can stare like Brigitte Helm, no-one raise her pencil-thin brows so intently, no one narrow her eyes with such intensity of willpower.) A rift is opening.

Jack is released. Back at the hotel, a fight between Manolescu and Cleo. He taunts her with the prospect of living a life of poverty. (Has the film lost all sense of orientation? Isn’t he the one supposed to be afraid of losing her?) He grabs her arm. Let me go, read her lips, and again and again. But he just wrenches hold of her, and they swirl. A grotesque parody of a lovers’ dance. He leaves. She weeps on a bed. (Again, what is she thinking?)

Jack arrives. She manages to half raise herself. He approaches, furiously. She has her back against the wall. It’s the same framing and pose exactly as the rape scene in the train. (How can the film be this intelligent in knowing how men treat Cleo, and yet proceed to treat Cleo as though she is the problem, the cause of men’s violence?) She somehow wrestles him into an embrace. She is squirming, desperate. She is on the bed, half-weeping, half-writhing into a new shape to enable her to survive. (God, Helm is magnificent: look at that face between her arms, raised to hide the shifting of her face, her train of thought, her pulse of cunning.) Jack looks bewildered. His eyes flashing under the breaking tide of black hair. She raises herself. He tries again to summon the will to strangle her. Their arms. Hers, bare and pale; his, thick and dark in his coat. Look at her shoulder blades, tensing, shifting. His face, gleaming with sweat. And now its her turn to strangle him into a kiss. His fury ebbs. His enormous face turns into that of a child, beaming at last with mad happiness. They have wrestled and a weird, mad pact resolved. She falls away from him, exhausted. “I’m so happy you’re back with me!” he says: the strangest line of dialogue after the preceding scene, one of the weirdest, most uncomfortable survival/attempted murder/seduction scenes I can recall.

Then Manolescu returns. Cleo between two brutes. Jack hurls a sculpture and hits Manolescu in the head. He falls. Cleo over his body. “Murderer!” she rasps, and Jack turns to leave—a giant lumbering from an inexplicable scene of defeat.

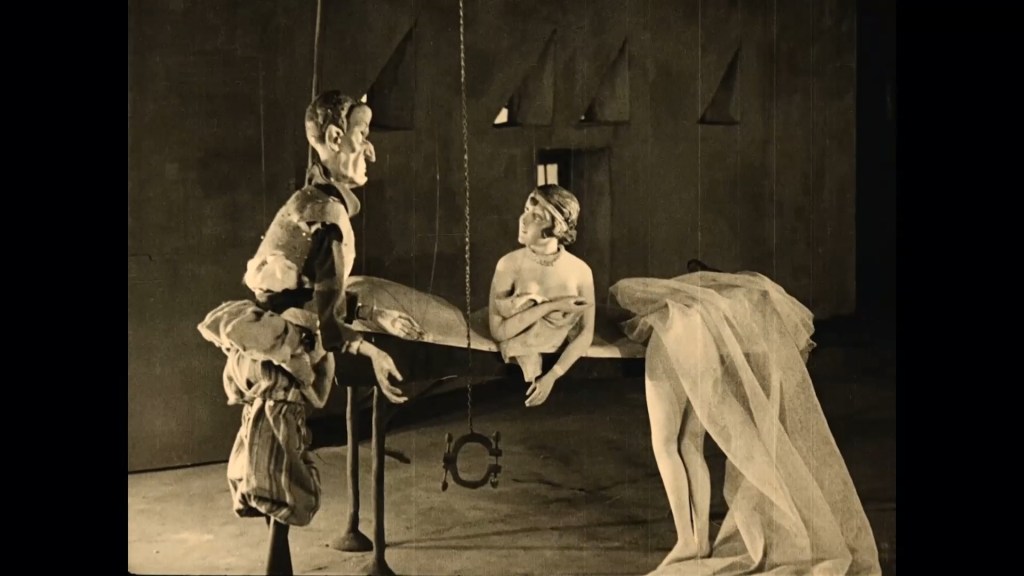

Cleo phones for the police. But look at Manolescu, on the floor. From the back of his head, in the shadows: that isn’t blood seeping from him, it’s electricity. Sparks are bubbling from his brain onto the carpet. The camera falls into them. The screen is the pulse of an electric sea. A vision of a courtroom. Faces and benches in the negative: black and white reversed. It is terrifying. The whole screen flickers uneasily. The electricity is still seeping, pulsing through his brain. Only Manolescu is in the positive: his face in profile in a scene of (literal) negativity. The crowd turns as one to stare at him. The judge rises: “Robbery… swindling… forgery…”. Manolescu stands: “Cleo… all… because of… you…”. The camera turns Manolescu on his side. He is no longer standing; he is in bed. A world of white. And Dita Parlo. She is Jeannette, a nurse with the warmest smile in the world. The film will take her side, the side that says “Cleo: all because of you” and blame Cleo for Manolescu’s own decisions.

Nurse and patient are falling for one another, but here is Cleo: “I am not to be blamed for what has happened… please, forgive me.” (The contradiction is clear, but what does the film want us to make of it?) “This is your doing!” shouts Manolescu as he sees another headline revealing his criminal work.

So Cleo departs and Manolescu and Jeannette go to the Alps to recuperate from his head injury. But Cleo visits: “We belong to each other”, she says, “I would never let anyone else have you!” “I hate you!” he hisses, and again hands and eyes are wrestling with fury. He rejects her. She catches sight of Jeannette. The two women look at one another. Cleo is contemptuous. (That raised brow, that narrowed eye.)

New Year’s Eve and Jack is drinking alone when Cleo turns up. Yet as soon as they embrace, Cleo is reluctant: “What abut Manolescu?… I have betrayed him.” Literally, this might be true—the police are on Manolescu’s trail, but how on earth are we expected to take Cleo’s logic? For now she is turned away. She is alone in the corridor, her black silhouette cast behind her on the wall. She walks away. The shadow lingers, then slips down and down the wall until it’s gone.

New Year’s Eve in the Alpine cabin. Manolescu and Jeannette and their host are having a party when two police agents arrive. Manolescu begs them to wait ten minutes so he can toast the New year with his lover. They acquiesce. Happy New Year drinks and deluded happiness. Then Manolescu must reveal the truth: they are here to take him away. Jeannette collapses beneath the Christmas tree. As he departs into the night snow, she runs outside and stands crying out that she will wait for him. This is the last image: a screaming woman, attacked by the howling night storm, pledging her love to a monster.

So that’s the film. And I’m very conflicted about it. I love Ivan Mosjoukine, I think Brigitte Helm is astonishing, and I’m a fan of Tourjansky. It’s a film made by UFA in 1928-29. This was the summit of silent filmmaking in Europe. This film has everything going for it. And it is indeed technically brilliant, sumptuous to look at, amazingly well preserved and presented, filled with spellbinding scenes and moments. But there is something at the heart of the scenario—and in turn, of the characters—that simply does not work, that is in fact exceedingly nasty. Even giving the brief synopsis at the start of this review was a struggle for me, for I gave the kind of synopsis you might see online for this film. Here is a different synopsis: Cleo is enslaved by her rapist, only to be blamed for his life of crime and rejected in order for Manolescu to “redeem” himself with a better woman.

After that early scene on the train, in which Manolescu decides he has a right to have sex with Cleo for “protecting” her, everything else is sullied. No matter how much I could talk about how fabulous it looks, about how great the performances are, I cannot get over the way the characters are conceived and conceive of each other and of themselves. The only way of making it make sense is to accept that Cleo falls for Manolescu despite the fact that in their very first scene together he imprisons her and then rapes her, then recaptures her again once she tries to escape. The unspoken condition that the film thinks it establishes—and which the film assumes somehow justifies Manolescu’s actions—is that Cleo sells herself. But she doesn’t sell herself in that first scene. There is no bargain, no conversation. We know nothing about her before she enters the train, other than that she is afraid and is hiding something. Over the course of the film, it’s clear what kind of life she’s led: but being subjected to the whims of male violence in order to live in relative luxury invites our (or at least, my) deepest sympathy, and deepest anger towards her exploiters. But for Manolescu and for the film, her associations make her the criminal. In the astonishing fantasy trial scene, among all the words used to describe him (“Robbery… swindling… forgery”), the word “rapist” is not mentioned. When the electricity starts seeping out of his head, I half wondered if the film was about to flip a switch and condemn Manolescu: were we about to watch him being dragged into hell? But no, his own self justification begins—and the film is complicit in constructing a redemption for this awful man.

The final section of the film is him finding a better woman than Cleo to love. All the film’s judgement falls upon Cleo, who is expelled from Manolescu’s life and then from Jack’s. Manolescu’s fate is to go to jail, but Jeannette awaits him. Are we really meant to sympathize with Manolescu? I find this utterly incomprehensible. If the film was about how awful Manolescu is, and how Cleo manages to find redemption and escape her life, then this review would be nothing but praise. As the film stands, I am alienated by the scenario. Is it the screenwriters’ fault? Is it a fault of the original novel, on which it is based? Or do we make some giant leap of faith and assume the film is somehow suggesting we do in fact take against Manolescu from the start, and that we should ignore the whole of the rest of the film’s story of a man pushed into criminality and then finding redemption?

I wish I could write a more coherent review, but the film compels and appals me in equal measure. I so wanted to love this film. It’s an extraordinary piece of work and a deeply uncomfortable watch.

Paul Cuff