One of the pleasures of writing about film history is how often you are proved wrong. When in 2016 my book about Abel Gance’s career during the transition to sound was published, I stated that there were no known copies of Das Ende der Welt, the German version of his first sound film. As I wrote here two years ago, this was not the case: a significant fragment of this version does survive in the collection of the Eye Filmmusem. In 2016, I also wrote that no known copy survived of the “international” (i.e. silent) version of La Fin du monde. Thanks to some propitious searching and corresponding, I have now discovered that this too is not the case. An excellent copy is held by Gosfilmofond in Moscow. As you may appreciate, a visit to this archive is currently impossible. However, thanks to Alexandra Ustyuzhanina and Tamara Shvediuk and their colleagues in Gosiflmofond, I have been able to see a digitized copy of this print.

First, a little context for this film. Gance’s first sound began production in 1929. Intended as an epic moral fable about the need for universal brotherhood, and starring the director himself as a prophet, it soon became clear that Gance’s ambitions far outstripped his material resources. By the summer of 1930, Gance’s personal and professional life had virtually collapsed. In debt, reliant on cocaine, his marriage ruined, and his film in chaos, Gance surrendered control of La Fin du monde to his producers. Gance had allegedly assembled a print of 5250m (over three hours) in late 1930, but the version released in early 1931 was 2800m and bears only a distant relationship with his intentions. The director refused to attend the premiere and publicly decried the versions shown in cinemas. (For the full story of this poisonous production, I refer interested readers to my book on the subject.)

La Fin du monde was intended as a multiple-language production. Initially planned to be shot and/or dubbed in French, German, English, and (so some sources state) Spanish, Gance eventually produced just two sound versions: one in French (La Fin du monde) and one in German (Das Ende der Welt). For the latter, only one member of the cast was changed, the rest either reshooting scenes in German with direct-recorded sound or else being dubbed via post-synchronized sound. La Fin du monde was premiered in Brussels in December 1930 and was released generally in France in January 1931. Das Ende der Welt premiered in Zurich in January 1931 and the film was released generally in Germany from April. (It says something of the oddity of this film that its two major sound versions premiered not in France and Germany but in Belgium and Switzerland.) An English-language version was released in the US in 1934, but The End of the World uses the French version as its basis – using subtitles and intertitles to present a version comprehensible to anglophone audiences. Given a new prologue and additional newsreel footage throughout, this is the most severely bastardized of all the versions released in cinemas in the 1930s.

However, one other version of the film was prepared for release in Europe. This was advertised as an “international” version, i.e. a silent version (often with a “music and effects” soundtrack, but no dialogue) prepared for the numerous cinemas still unequipped for sound exhiubition. It was purportedly prepared by Eugene Deslaw (Le Figaro, 2 August 1931). Deslaw had evidently worked as one of a great many official and unofficial assistants for Gance during the production. During this time he assembled Autor de la fin du monde (1931), a curious short film that contains both behind-the-scenes footage and scenes cut from the version released in 1931. (Including one shot, of Antonin Artaud, that is one of the most astonishing close-ups Gance ever filmed.) However, the history of his editing of this film and of the “international” version of La Fin du monde is unclear. As far as I can ascertain, the premiere of Autour de la fin du monde was February 1931, in a gala evening hosted by Gance. But I can offer no such detail for the distribution of the “international” edition of the feature film. Adverts do not usually state any details of length or soundtrack, so it is very difficult to trace what – if anything – became of this version. Back in 2016, I could find no evidence that any copy of the film survived. But, as ever, I was to be proved wrong. Gosfilmofond’s print runs to approximately 2484m, just under ninety minutes, and features a synchronized music-and-effects soundtrack without dialogue. Whether this represents a “complete” copy of this version is difficult to know, but it is certainly shorter than the 2800m version that was released in 1931 – and shorter than the c.2600m restoration of the French sound version that was released by Gaumont on DVD/Blu-ray in 2021. So, what does the international version look like? And sound like?

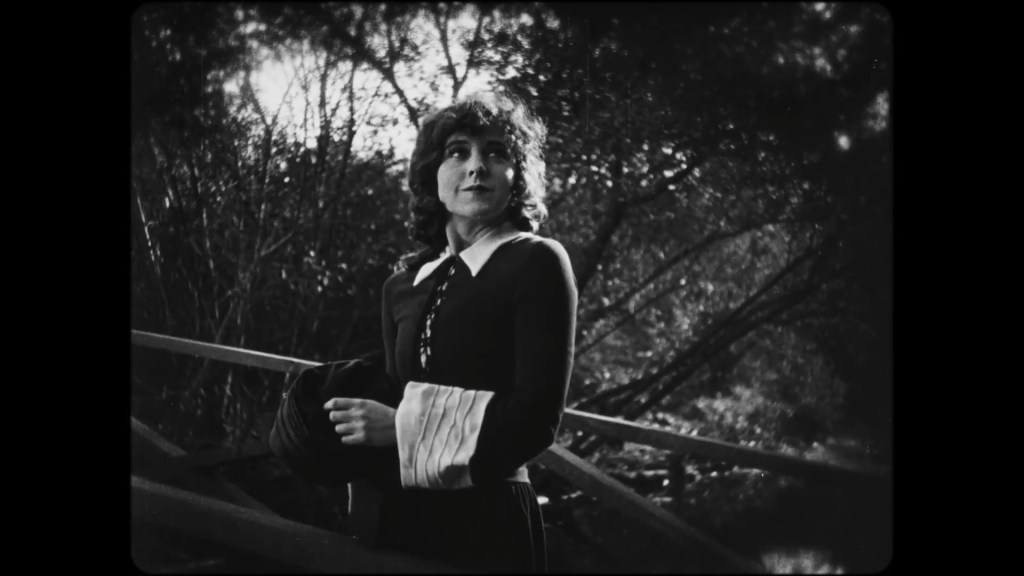

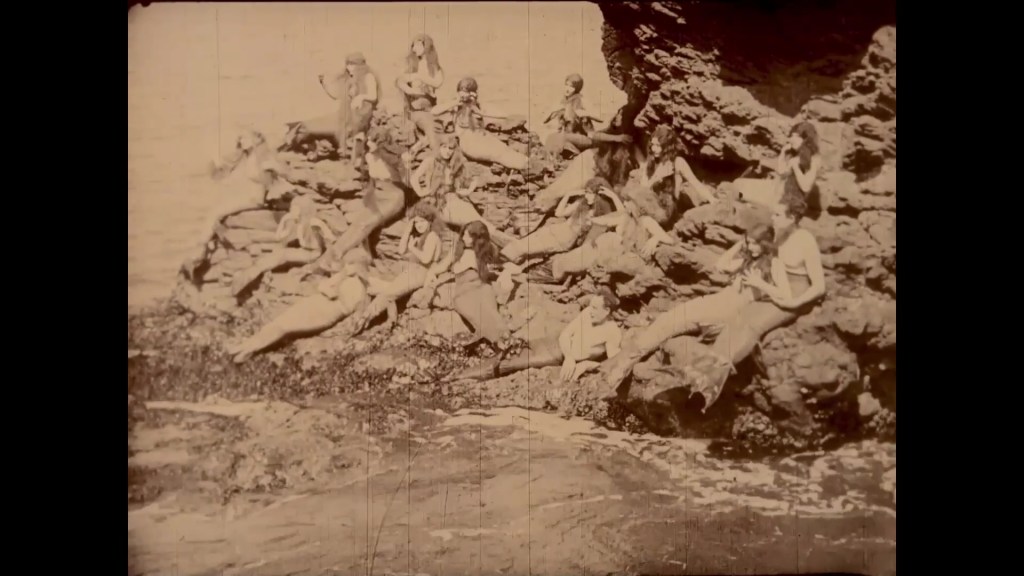

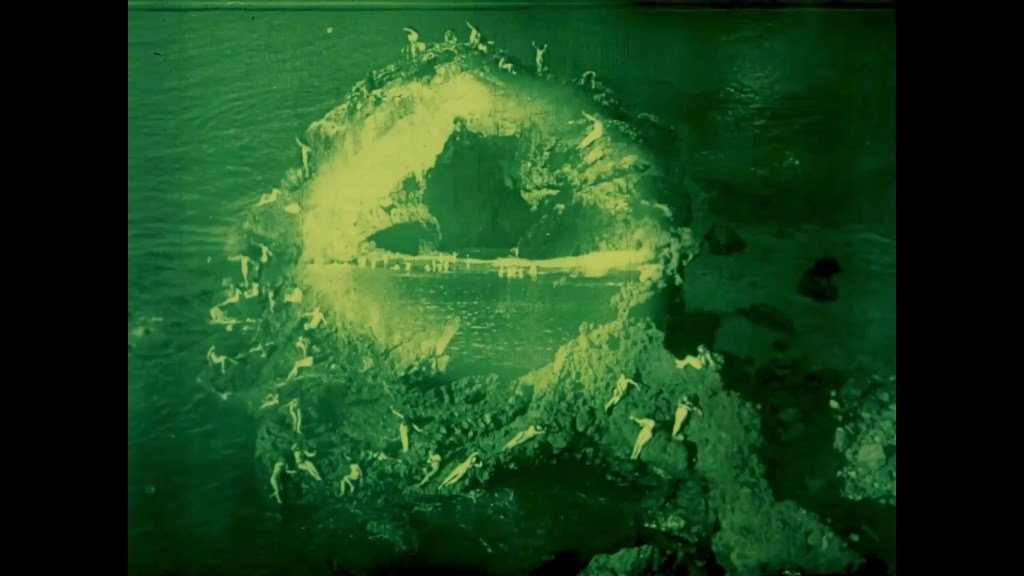

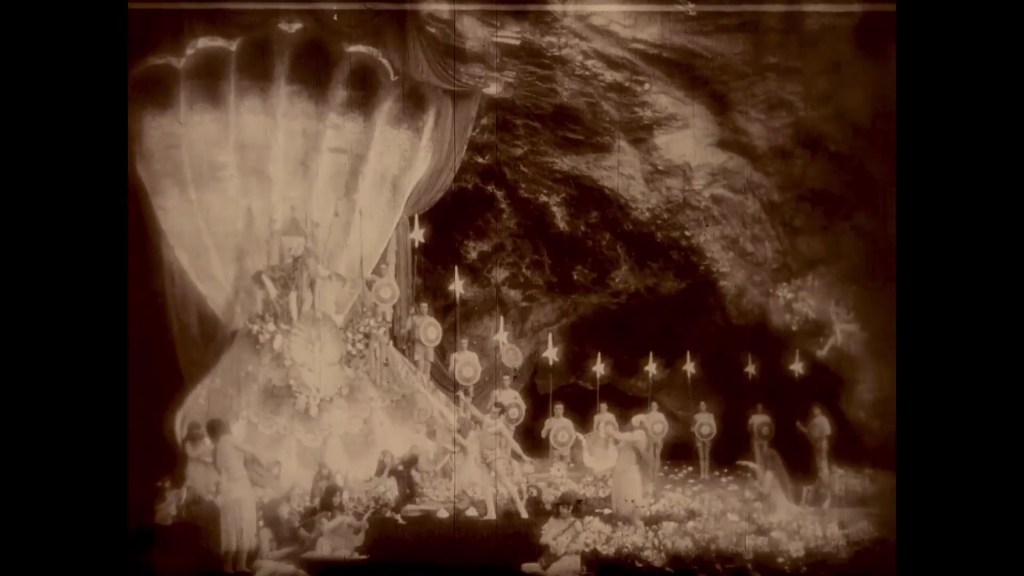

While the (surviving) French sound version opens with text superimposed over some jerkily assembled aerial shots, the credits of the silent version unfold over a blank screen and are clearly complete. The opening music cue (Tchaikovsky’s Francesca da Rimini [1877]), curtailed and abrupt in the sound version, is here complete and ends just as the opening images begin. These first shots, too, are entirely missing from the French version. Rather than open on the interior of the church hosting the performance of the Passion, we see the exterior and the poster for the play. Geneviève’s name is on the poster, which rather neatly serves as her introductory title – for the film now cuts straight to her in close-up in the play, as Mary Magdelene. There are several extra shots of the Passion group before we reach the point at which the French version begins (at least in the Gaumont restoration). The music and sound effects for this whole opening sequence are the same as in the sound version, though the montage is briefer and there is no dialogue between the various characters we meet in the audience.

In the following scene between the brothers Jean and Martial Novalic, there is the first (of many) music cues that are not in the sound version. Here, we hear the ‘Largo’ from Handel’s Serse (1738), as arranged for piano and cello. This scene plays very differently than in the sound version. This scene plays very differently than in the sound version, with the dialogue is conveyed through intertitles. I confess that I found this scene weirdly moving. Perhaps it was the music, which gave a wonderful sense of intimacy and solemnity to the scene; certainly, it was in part due to the sheer novelty of seeing this scene for the first time in silence, which saved me from hearing the very thin sound design of the dialogued version – and Gance’s peculiarly bathetic vocal performance.

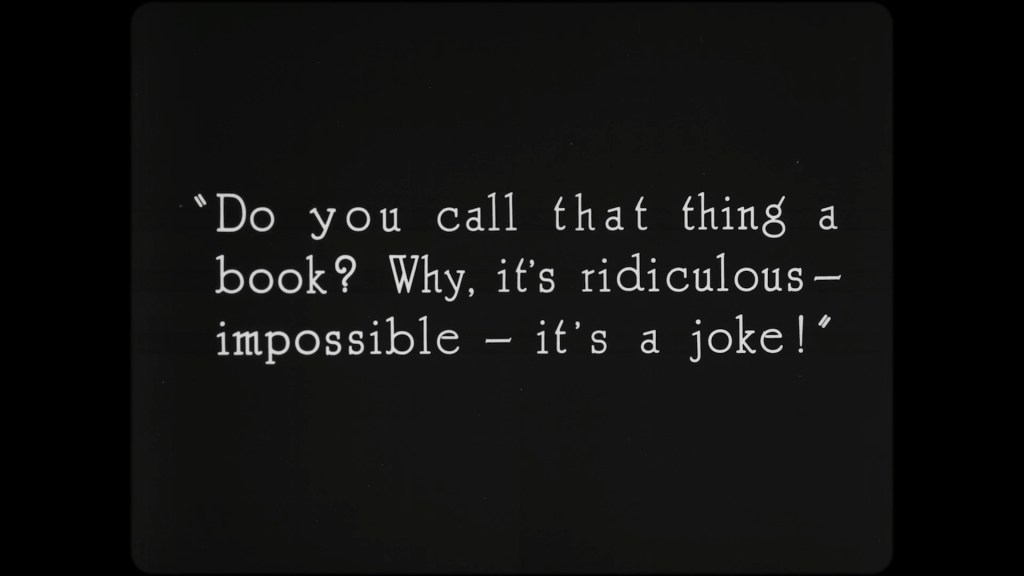

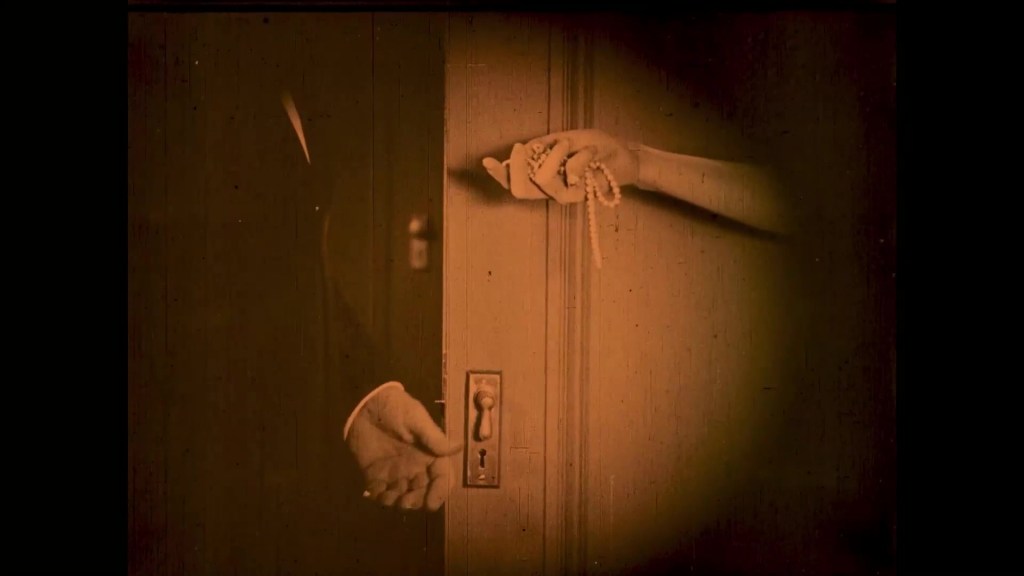

Another factor is that the montage is totally different from the sound version. Not only is the editing different (regardless of the inserted titles), but so too the camera angles and the performances. Deslaw is clearly using not just material from a different camera but from different takes. (This material was clearly shot at 24fps, the speed for synchronized sound, unlike the material visible elsewhere in the film that was shot silently at a noticeably slower framerate. Presumably, therefore, this material was taken from takes that originally had a soundtrack – not from takes shot silently.) Even the inserted close-up of the book that Jean shows Martial is different. The text is slightly shorter in the sound version, while the silent version shows the wider page and the page number. The silent version of the scene is longer, more smoothly edited, and ends differently – with the two brothers walking arm-in-arm from the scene. The sound version has an awkward insertion of a close-up of Jean and ends with a sudden fade to black before their discussion ends. The montage in the sound version is awkward, the composition tighter – next to the silent version, it looks almost cropped.

The same pattern is evident in the next scene. These are different takes of the same scene, shot from a different camera position. Again, the silent version has the camera placed slightly further away. I think the composition of the scene is improved, with the blocking of Geneviève, De Murcie (her father), and Schomburg clearer and more effective.

In scene after scene, this continues to be the case. Everything is subtly different in the silent version. It follows the same narrative line but uses different takes and different editing. Sometimes, the sound version has an extra scene, sometimes the silent version has an extra scene. But the overall shape is the same. (You could easily use the scenes in one version to plug gaps in the other.) But again and again I am struck by how awkwardly framed and edited the sound version looks in comparison with the silent version. Even when the content of sequences is shot-for-shot the same, the choices in the silent version look more balanced, more carefully chosen, and better put together. The sound version consistently looks far too tightly framed, with the tops of characters heads just out of shot, or characters standing just off-centre, or floating oddly at the edge of the composition.

The more bravura scenes of editing are also significantly different. The rapid montage of Jean’s madness is more neatly handled in the silent than the sound version, and it reaffirms my longstanding impression that the montage in the sound version is clunkily curtailed at the end. Likewise, the rapid montage in which Schomburg plummets to his death in the lift of the Eiffel Tower is longer, more dramatic, and more coherent in the silent version.

More broadly, there are significant gaps are that either version fills in for the other. While Schomburg’s rape of Geneviève is missing from the silent version, the scenes of journalists spying on the scientists as they confer on Martial’s discovery are missing from the sound version. Later, there is a more significant scene where Martial and his team return to the control centre where they had formerly had their headquarters. The centre was raided and damaged (a sequence we see in both version of the film) but now, after Schomburg’s death, the team reassembles. Martial is despondent, but Geneviève arrives and encourages him (in Jean’s name) to resume the struggle for humanity’s salvation. The pair embrace and Martial then gives a speech to his team that reinspires them to begin broadcasting their universalist message. (I had spotted one shot from this sequence in the Eye Filmmuseum print of the German version, and had assumed it came from a later (also lost) sequence, but here I saw it again – and now I understand its proper place.) This whole sequence is only in the silent version, and makes the finale make more sense. Seen with titles and no dialogue, accompanied on the soundtrack by the opening movement of Franck’s Symphony in D minor (1889), I found Martial’s stirring address (“Victory lies in your work, in your enthusiasm…”) oddly moving. (And this is a film that has never moved me!)

Curiously, there are also other scenes that appear in different places in either version. In the silent version, we see Martial’s attempt to warn the press of the impending collision of the comet, and then Werster’s agreement to support Martial, much earlier in the narrative than in the sound version. I think this actually makes the narrative clearer, even if the surrounding subplot of the press war is not well developed in either version of the film. (In Gance’s screenplay, as ever, everything is given much more time to unfold coherently.)

The final minutes, including Martial’s declaration of the “Universal Republic” and the surrounding impact of the comet, is the one section of the silent version that is less convincing. The montage leaves out much that is crucial to understanding Martial’s gathering of world leaders. And while there is certainly different footage of the worldwide panic, it is no more convincingly put together than in the sound version. In both silent and sound films, the film falls apart in an orgy of incoherence. The finale ends on the same imagery, with minor differences in editing, and is equally unconvincing – and not what Gance intended. FIN.

What to make of the Gosfilmofond copy, and of this silent version of Gance’s first sound film? Firstly, I think it’s a better viewing experience than the sound version. When the narrative is the same between versions, the framing and editing in the silent version is usually superior. That said, the silent version is not as coherently edited as a true silent production. The use of intertitles is not consistent. No character is given an introduction through titles, and there are few narrational titles to explain what is happening. Sometimes, indeed, the fragments of recorded sound on the soundtrack take the place of intertitles. This “international” version is not a sound film, but nor is it a true silent film. Though it is unfortunately missing many important scenes from the sound version, it adds other important scenes of its own. Put together, you might have a more coherent narrative. It reaffirms just how shoddy is the assemblage of even the more coherent scenes in the sound version.

But these very qualities also raise more questions than they answer. What kind of control did Eugene Deslaw have over this silent version? What material was he allowed to use, and why? When was this version assembled, and on whose instruction? Per my comments above, Deslaw clearly had access to footage from different cameras and different takes. He also must have had access to parts of the soundtrack before they had been mixed with the direct-recorded dialogue elements. (In the scene of Jean’s madness, for example, he uses the same section of music per the sound version but without the latter’s added dialogue.) Yet despite the presence of some extra scenes, Deslaw doesn’t include any of the dozens of more significant scenes that Gance shot in 1929-30 which were cut by his producers prior to the film’s release in 1931. Fragments of this mountain of extra material may appear in Autour de la fin du monde, but it is nowhere to be seen in the “international” version of La Fin du monde.

In summary, the Gosfilmofond print is a document of major importance in our understanding of La Fin du monde. I long to know more about the history of this particular print, and about the “international” version it represents. While I think many aspects of it are superior to the sound version (at least to the French version that survives), it remains very far from the version that Gance assembled in 1930. But its survival is itself a small miracle, and raises hope that other miracles are out there in archives, waiting to be discovered…

Finally, I offer my deepest thanks to Alexandra Ustyuzhanina and Tamara Shvediuk, and to their colleagues, for their help with accessing material in the Gosiflmofond collection.

Paul Cuff