It’s another packed day of material from Pordenone: we get a short and no less than two features. While not quite as lengthy a programme as Day 2, it’s another full schedule for the eyes. We begin in Italy before heading to Hollywood’s high seas…

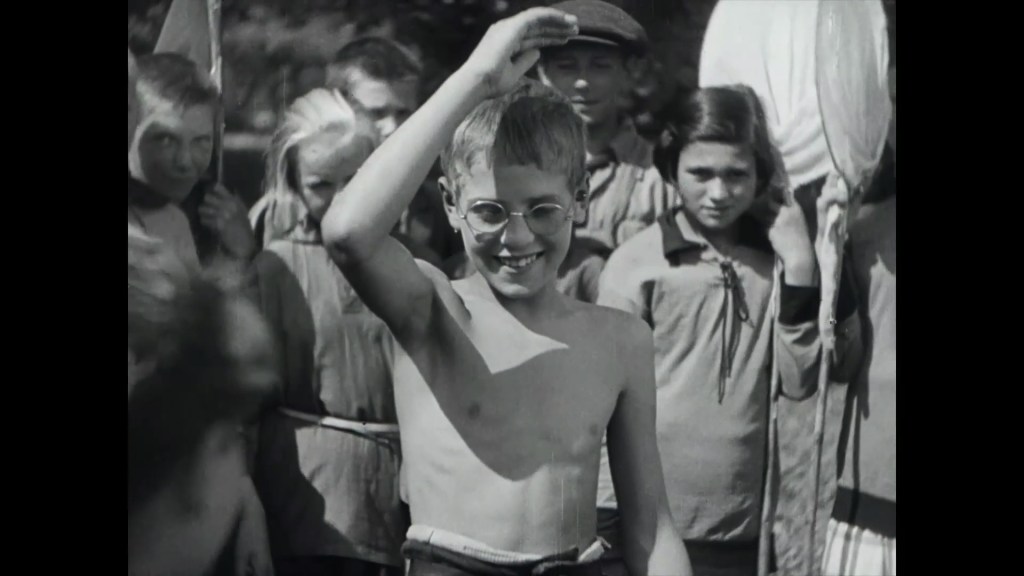

Colonia Alpina (1924-29; It.; Emilio Gallo). Our short film is a series of views of a school trip to the mountains. The opening title contains an excusatory note from the filmmaker, Emilio Gallo, apologizing for the poor quality of the material. But despite the claim of being an “amateur” production, there is much here to admire. As ever, I love this kind of fleeting glimpse into the world of the past…

A troupe of schoolchildren march along mountain pathways. Their eyes stray towards the camera as they ascend the steps to their lodge. They are served food, still glancing over their shoulders at us. They half-march, half-tumble down a slope. Their eyes catch ours. A boy salutes, and vanishes. Exercises beneath the trees and a burnished sky. The tinting – pale amber, pale green, pale pink – makes each scene glow with warmth, with the ghost of sunlight and foliage. The children scamper and laugh, innocent of their ancientness. They raise their arms in fascist salute. They are long dead, now, and they cannot imagine why we are troubled.

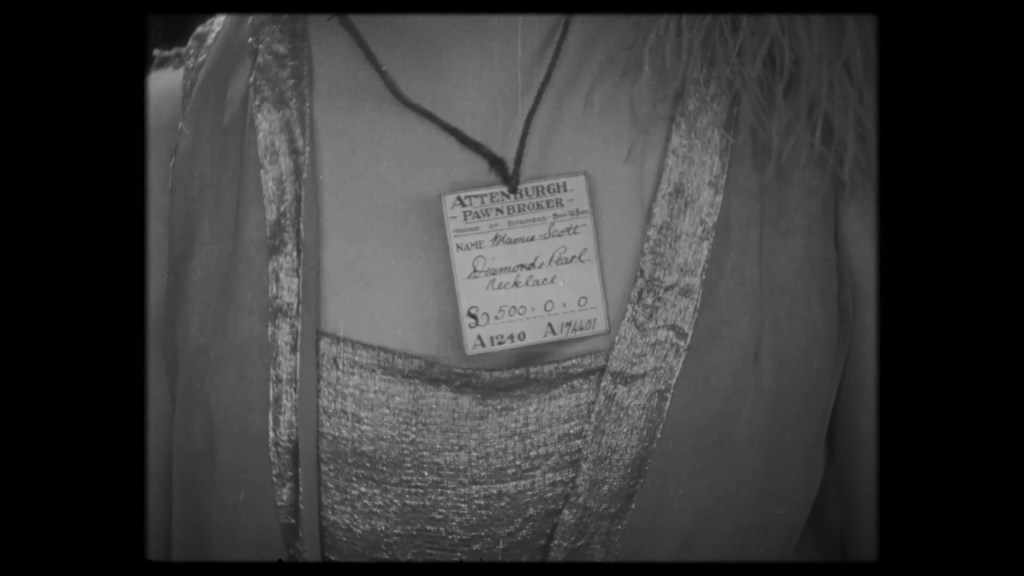

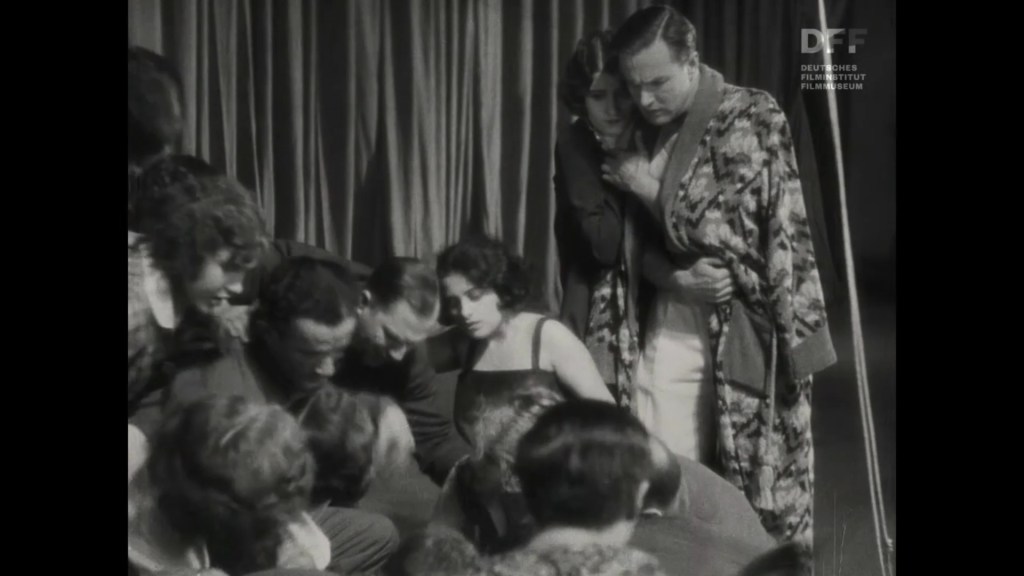

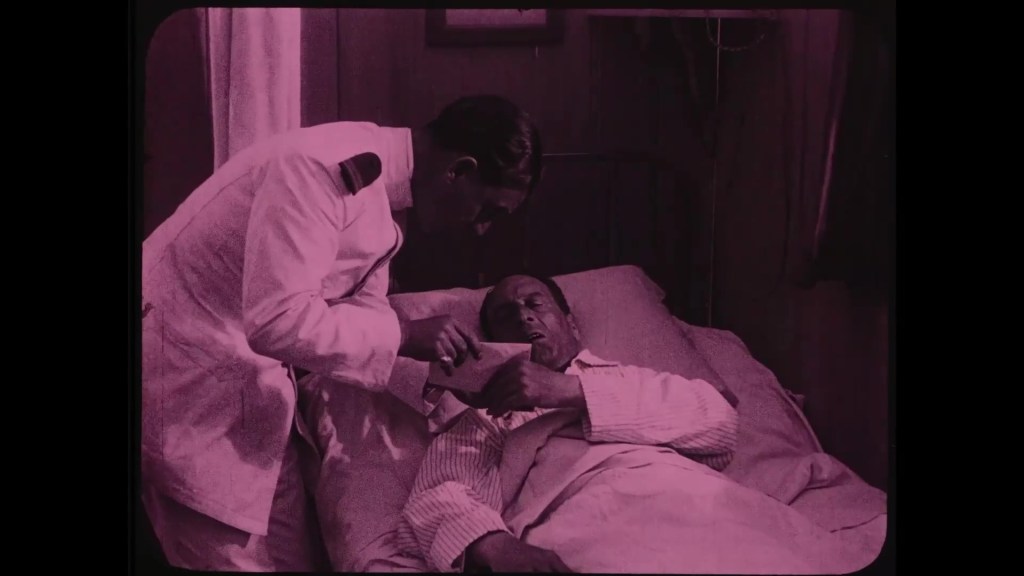

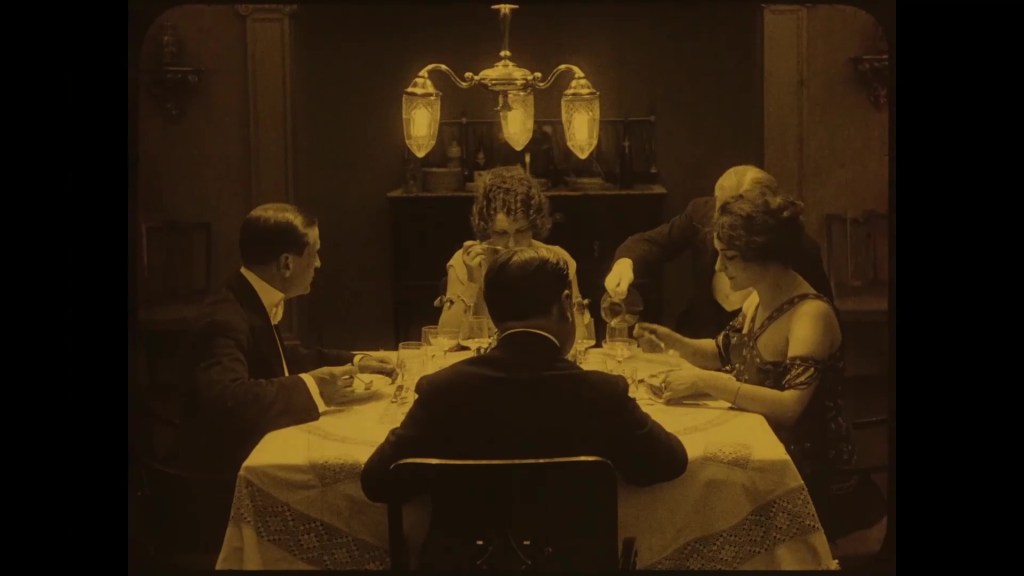

Il siluramento dell’Oceania (1917; It.; Augusto Genina). The Pacific. Warships at sea. Onboard the “Titan”, the Count and Countess de Martinval, and Baron Cocasson, who tries to flirt with the countess – little suspecting that both she and the count are criminals. Meanwhile, onboard the nearby “Oceania”, Captain Soranzi is asked to the bedside of the dying Marquis de Roccalta. Roccalta entrusts him with a letter to his daughter, Jacqueline, saying that the family fortune is hidden – and the instructions to find it lie in the hilt of the sword of the “Terrible Knight”. But the “Oceania” is torpedoed. Before the ship sinks, Soranzi messages the “Titan” with the news of the disaster – and the clue to Roccalta’s treasure. The signaller onboard the “Titan” takes the news of the treasure to the Martinvals, who decide to pursue the fortune. At Castle Roccalta, the widowed Marquise (who does not yet know that she is widowed) is heavily in debt. Her daughter Jacqueline is engaged to Henri de Ferval, and lives in ignorance of her impending destitution. The creditor Isaac is already taking inventories of the family jewels to take in lieu of payment. When the loss of the castle occurs, de Ferval abandons Jacqueline and the family must move out. Baron Cocasson exploits the situation, paying Isaac for ownership of the castle. While the Cocassons search for the treasure in the chateau, the impoverished Marquise dies – entrusting Jacqueline to the care of their loyal butler, Fidèle, with the desire that they should go to America. Meanwhile, news reaches Cocasson that Soranzi has miraculously survived the sinking and is now on his way to contact Jacqueline. When Soranzi arrives, the countess pretends to be Jacquline and receives the letter from her late father. While the villains search for the treasure, Soranzi travels to America and is feted at a soiree at which “Miss Dolly” performs. “Dolly” is none other than Jacqueline, who has come to America in search of her father – not knowing his fate aboard the “Oceania”. But the Martinvals are also now in America, searching for Jacqueline, who unknowingly holds the final clue to the treasure in her necklace pendant. When Soranzi realizes their deception, a chase ensues. The various parties head back to Castle Roccalta. The villains find the treasure, so another chase ensues. Eventually, Fidèle captures the villains in the mountains, allowing Soranzi to marry Jacqueline – and secure the treasure for their future. FINE.

As you can tell from the above synopsis, this is a madly diverting film, packed with madly zigzagging twists and turns. The restoration credits do not make clear the original length of this production, and the copy presented here is a French edition with some missing scenes explained by text. It feels like a much longer serial film has been condensed into 70 minutes. That said, the whole thing is extraordinarily entertaining – full of absurd twists and turns, sudden relocations, inexplicable plot devices, and characters that appear and disappear. Though I was never once moved, I was always engaged. Il siluramento dell’Oceania has all the pleasures of a serial – dastardly villains, killings, death by grief, hidden treasure, kidnapping, false identities, umpteen chases on planes/trains/automobiles – all delivered with great aplomb. It’s incredibly silly, but huge fun.

Plus, it looks absolutely gorgeous. The tinted and toned print preserved by the CNC is superb quality. The location shooting around Italy is superb. I love the sharpness of the highlights, the glow of the colours, the richness of the blacks. We get to see a wide variety of locations, from the high seas to the snowcapped mountains, and there are glimpses of gorgeous castles and dusty roads, as well as all forms of transport: ocean liners, trains, cars, planes, and bicycles. The characters might be cardboard, but they chase around these fabulous landscapes with marvellous commitment. When everything looks this good, and moves along with such gusto, it simply doesn’t matter how pulpy the story or situations. What a wonderful, mad rush through 1917. (Though I hate to keep picking on it, Day 3’s The White Heather lacks precisely the energy, fun, variety, and silliness that makes Il siluramento dell’Oceania so enjoyable and so rewarding.)

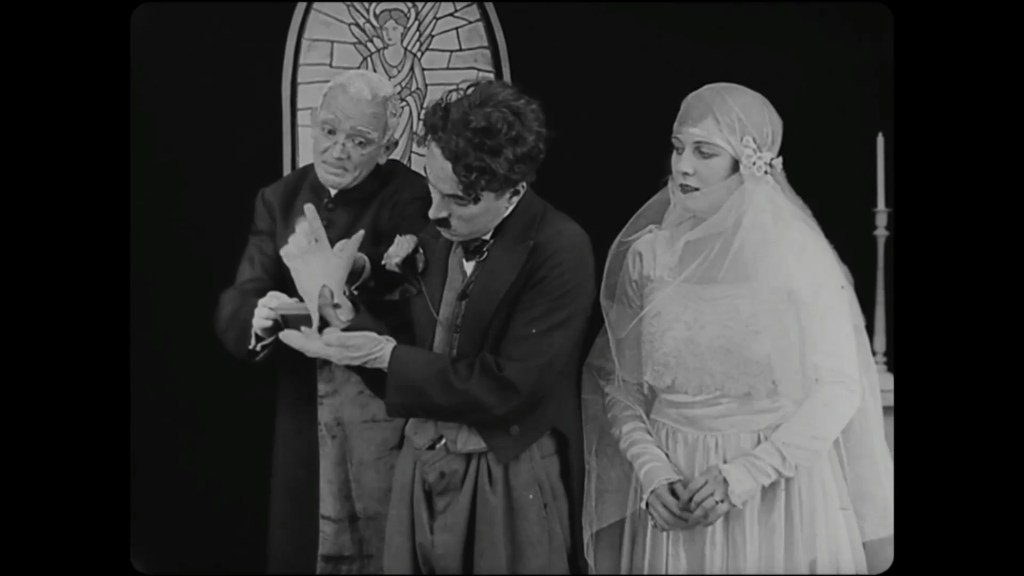

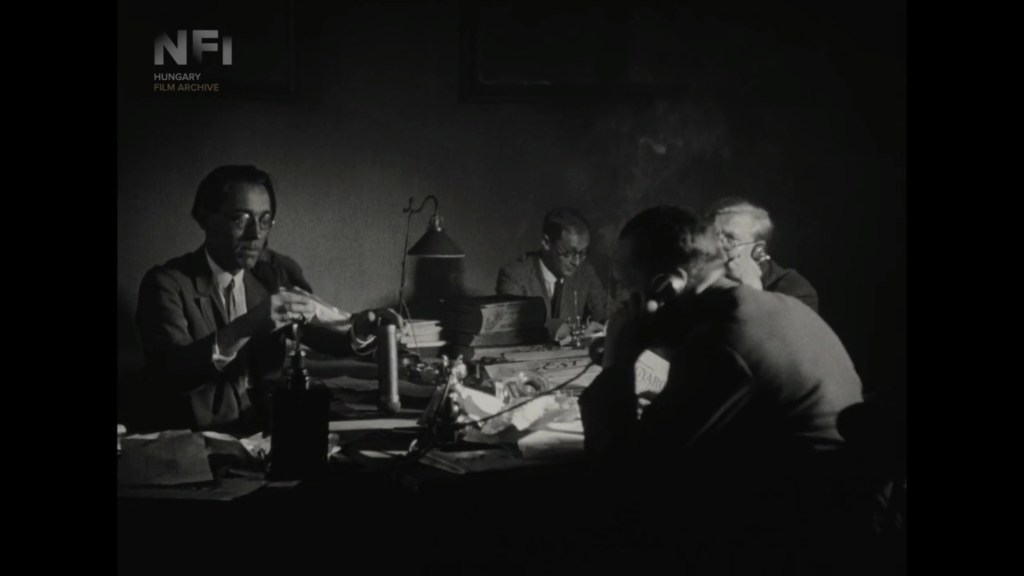

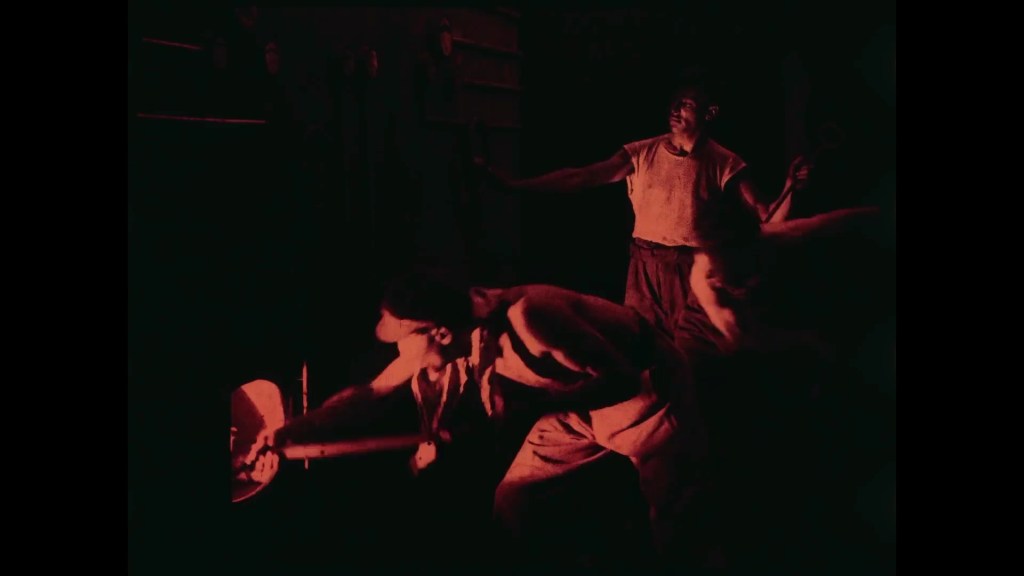

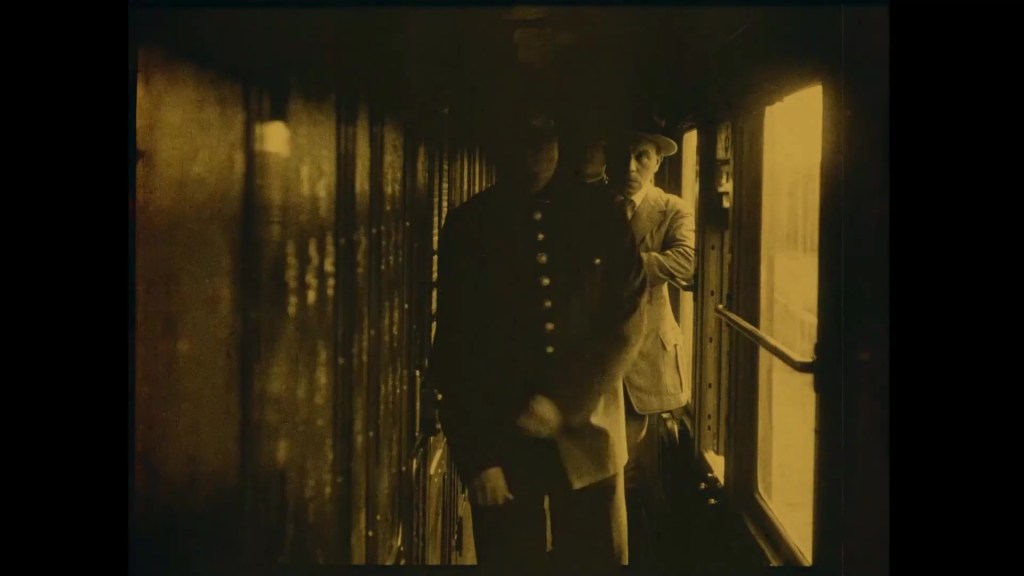

The Blood Ship (1927; US; George B. Seitz). Our second feature takes us aboard “The Golden Bough” in the 1880s, with its cruel captain “Black Yankee” Swope and his daughter Mary, who hates her father’s treatment of his crew. In San Francisco, Swope recruits a fresh crew from the harbour inn, run by “the Swede”. Mary takes the chance to run ashore but bumps straight into the sailor John Shreve. Swope forces his daughter back on board, so John decides to volunteer for the crew – as does the veteran James Newman. Most of the crew have effectively been kidnapped by the Swede, including a reverend and a diverse group of roughs from the inn. Newman confronts Swope, who kidnapped his wife and daughter (Mary) many years ago. Newman has served time for a murder Swope committed, leaving Swope free to raise Mary as his own child. The brutality of Swope and his second, Fritz, leads to the death of a young crewman. Newman is tied up and taunted by Swope, who reveals that he killed Newman’s wife. Mary overhears the truth, just as the crew mutiny. Fritz and Swope are killed and dumped overboard, and the ship sails back to San Francisco – where John and Mary can marry. FINIS.

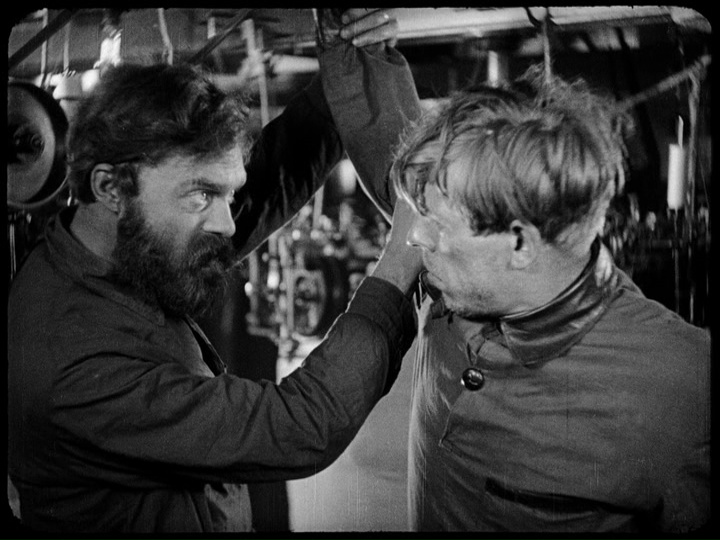

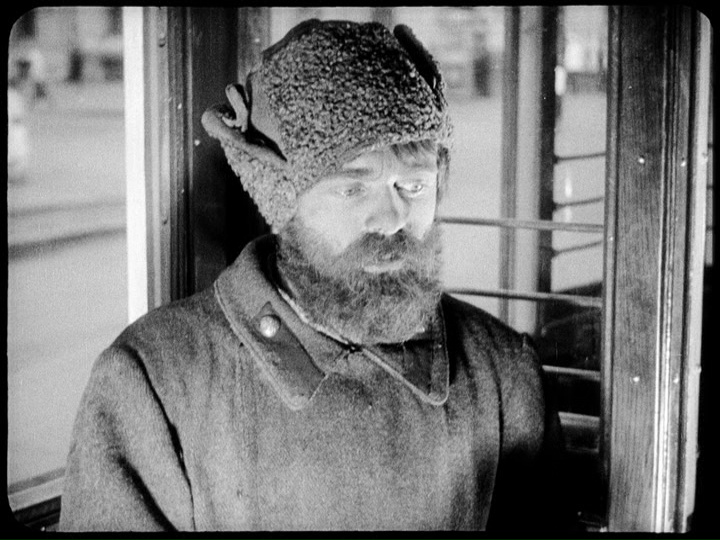

Hmm. Well, as a drama this at least has the merit of brevity. At about 65 minutes, the film has enough plot to keep it going, but no more than that. The characters have little depth or complexity, nor are there any surprises. That said, the entire cast provide very committed performances. As James Newman, Hobart Bosworth has an especially arresting face and piercing eyes. He has tremendous presence as the wronged father and widow, and you absolutely believe in his implacable hatred and sense of mission. When he whips Swope to death, hurls his body overboard, then stretches out his arms in a gesture both of relief and triumph, it’s genuinely thrilling and disturbing. Jacqueline Logan and Richard Arlen (as Mary and John) are a very handsome couple. Both players do their best with these roles, which is enough – but no more than enough.

The cast as a whole are a series of stock, if not stereotype, characters. What’s interesting is how many “types” there are. Swope’s sidekick is called Fritz, the innkeeper is the Swede, and among the cast are Nils (Scandinavian) and the black sailor. Accents are made evident in the dialogue titles, with the latter two characters in particular having distinctive speech patterns. While the black sailor is the centre of various comic moments, he is (mostly) the originator of the laughs rather than the object of them. When another crew member ends up falling into some tar, there is an awkward moment of blackface humour – but thankfully it is the white sailor who is the subject of the black sailor’s joke. The black sailor is played by Blue Washington (who was also a baseball player), who appears last on the credits – and his character is unfortunately named simply as “The Negro”. Which is, I suppose, the kind of depth and detail one might expect from a story like this.

Despite these limitations of character and plot, the film does work. Indeed, it’s impressive that it is so successful at sustaining the drama across even 65 minutes without falling into piratical parody. The Blood Ship is very well lit and photographed and has a marvellous set and setting. The titular ship is a real and believable space, the perfect self-contained setting for the drama. The quality of the print used for this restoration is excellent, and it’s beautifully sharp and detailed. Faces have amazing texture, eyes gleam with superb clarity, and the ropes and wood of the ship have palpable weft and grain.

What more can I say? I enjoyed the film, but my brain was once more feeding on scraps. What sustained me throughout was Donald Sosin’s superb piano score. Absolutely committed to the drama, it was alternately swashbuckling, violent, tender, and tuneful. A real delight. Piano music for the two Italians films was provided by Jose Maria Serralde Ruiz, which was likewise excellent: playful, wistful, curious for the short, and energetic and expansive for the feature. So yes, a diverse range of entertainment: films that I would never otherwise have seen, presented to their best advantage.

Paul Cuff