This post is inspired by the release of Ridley Scott’s Napoleon (2023), which I discussed with Jose Arroyo and Michael Glass on their wonderful podcast series Eavesdropping at the Movies. (The episode is available for free via the podcast website here.) Having talked about various screen Napoleons on the podcast, I thought I might revisit the various versions that Gance planned and made across his career. (I was planning on writing about Sergei Bondarchuk and other more modern versions, but Gance at least has more basis in the silent era and thus would be more relevant to this blog. I must obey my own remit…) For a full history of allthe manifold variants of this project, I refer interested readers to Kevin Brownlow’s book “Napoleon”, Abel Gance’s Classic Film (2004), and to Georges Mourier’s article “La Comète Napoléon”, Journal of Film Preservation, no. 86 (2012): 35-52. But for the sake of something approaching brevity, here are the major projects across his career—with some flavour of their content:

Napoléon, vu par Abel Gance (1927; Fr.; Abel Gance)

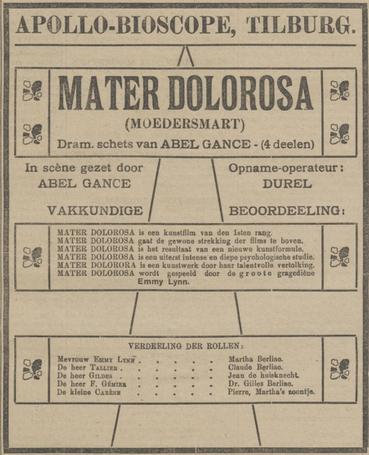

In 1923, Gance began work on a film series that he believed would stand as a monument to the creative power of European cinema. Financed by a society of backers across the continent, its size and commercial appeal should rival even the most spectacular of Hollywood’s “super” productions. Gance’s project was a biopic of Napoleon Bonaparte that would consist of six films. “Arcole”would cover the years of Bonaparte’s youth and early military career (1782-98); “18 Brumaire”, his campaign in Egypt and seizure of power in France (1798-1800); “Austerlitz”, from his coronation as Emperor to dazzling military victories across Europe (1804-08); “The Retreat from Russia”, the route from peaceable treaties to disastrous campaigns in eastern and central Europe (1809-13); “Waterloo”, his abdication, then his escape from Elba to France and final defeat (1814-15); “St Helena”, his last years and death in exile (1815-21). An epilogue would show the return of his earthly remains from St Helena to France in 1840.

During his research, Gance went through a small mountain of literature on Napoleon and the French Revolution. His purpose was not merely to reassemble the detail of an era, but to locate and reanimate its spirit. Gance contacted Napoleon’s descendants, hoping to gain an endorsement (or even money). He told Princess Clémentine of Belgium (the wife of Napoleon’s great-nephew Prince Victor Napoleon) that the “elevation” of his “sublime” mission would be supported by “a moral religion”. This “religion” was cinema. Napoléonwould be a “miracle” possessed of “radiant permanence”, a work of revelation more than mere education or entertainment. All the screens of the world “anxiously await the living history of the Emperor”, and Gance deemed himself “the architect of this Resurrection”:

Intuitively, I feel the stirring of the Emperor’s Shadow in response to my effort. If he was alive, he would deploy this wonderful intellectual dynamite of the cinema to be loved wherever he was absent, to be everywhere at once in people’s eyes and in their hearts. Dead, he cannot object to our modern alchemy transmuting his memory into a virtual presence to better enhance his Imperial Radiation.

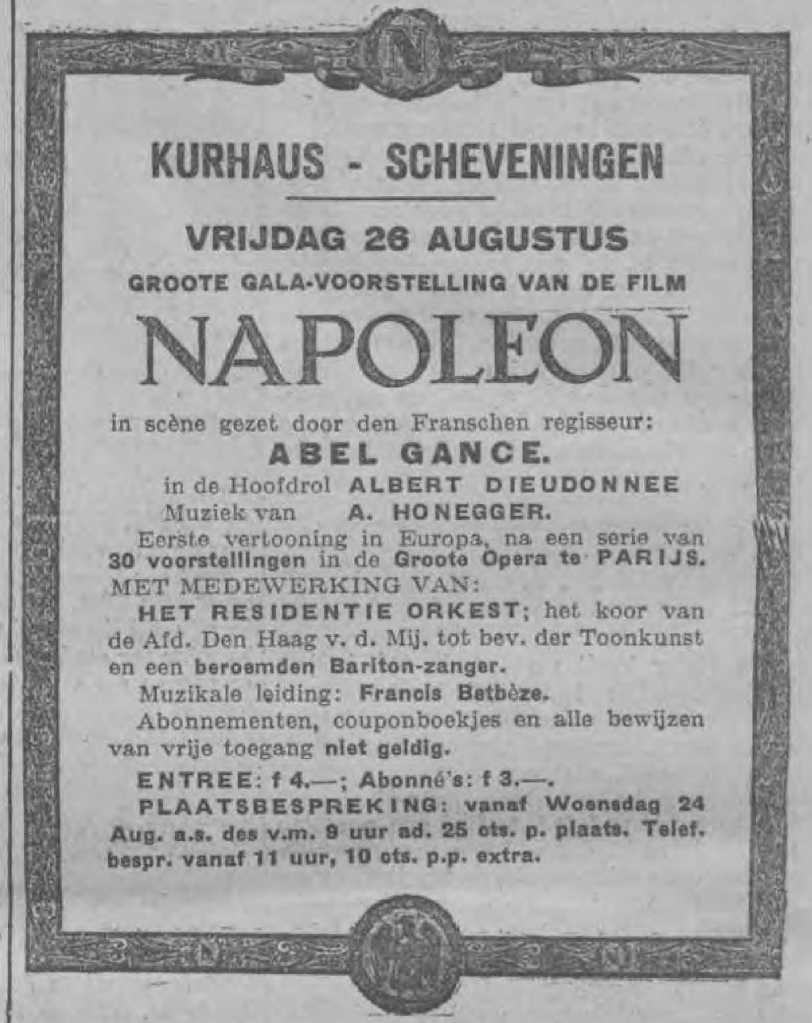

The curator of Fontainebleau palace, Georges d’Esparbès, allowed Gance to write his first screenplay in the Emperor’s former rooms there. Immersed in the Napoleonic past, visitors to Gance’s candlelit workstation in 1924 described the atmosphere as one of a “spiritualist séance”. Turning up in costume to clinch the lead role, Albert Dieudonné convinced an elderly museum attendant that he was the ghost of Napoleon—and would do the same to some inhabitants of Corsica when filming there the next year. Gance demanded that his whole cast faithfully inhabit their roles, desiring them to “become” their ancestors. Thanks to his inspired direction, actors threw themselves into their roles with an enthusiasm that Emile Vuillermoz anxiously described as a kind of “possession”. Witnesses like Carl Dreyer were taken aback by the zeal with which the conflicts of the 1790s was being re-enacted in the 1920s. As far as Gance was concerned, he was channelling the past. Looking back on his work in 1963, he called Napoleon “the world’s greatest director” and in 1979 he suggested that his silent film was a documentary record of historical events reliving themselves before his cameras.

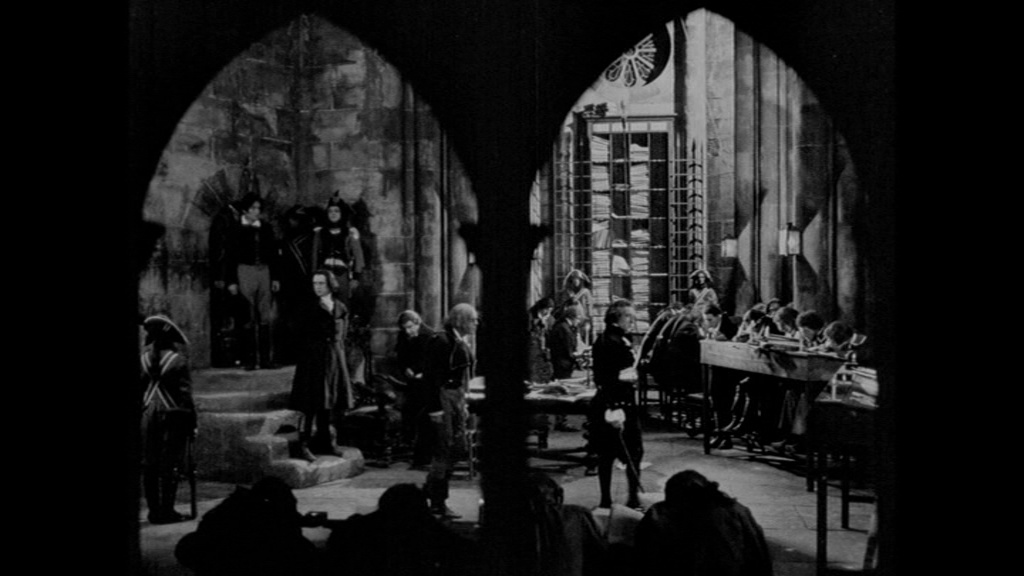

When he embarked on this enterprise in 1925, Gance wrote that the spectator too must become an actor and “participate” in the drama on screen. For Napoléon, he liberated the camera further than any previous filmmaker: mounting devices on the chests of cameramen, on the backs of horses, on rotating platforms, swinging pendulums, cars, sledges, horseback, and even guillotines. This is a panoptic view of history. Gance gives us access to the viewpoints of characters and of the spaces they inhabit: we are thrown into the snow at Brienne; we nervously scan a sea of faces at the Cordeliers club; we chase Bonaparte across Corsica; we swoop over Paris crowds; we dive into the Mediterranean. By overlaying multiple images within a single frame, Gance combines diverse perspectives; by cutting them together at frenetic speed, he wrenches the viewer from their fixed point of view and propels them into the tumultuous past. Nowhere is this sensation more evident than in the triptych of the film’s last sequences. The revelation of images across three parallel screens is one of the greatest moments in cinema. This expanded frame is exploited with masterful confidence: Gance’s widescreen offers panoramic shots of immense depth and breadth. Yet it is perhaps when he splits his composition into three separate planes that Gance achieves his most radical ambition. The final moments of Napoléon overlay time and space; mingle subjective and objective imagery; show simultaneously the past, present, and future.

The realization of this grandiose vision came at a cost. The production of Napoléon in 1925-26 exceeded all its assigned parameters of time and finance. Gance’s shooting script had grown to the size of a large novel, yet had chronologically reached only as far as April 1796. In shooting just two-thirds of what he had planned to cover in the first of six films, Gance had consumed 400,000 metres of celluloid and spent the budget for his entire series. After months of editing, the film premiered at the Paris Opéra in April 1927. This four-hour version (with two triptych sequences) was followed by a ten-hour “definitive edition” (without triptychs) at the Apollo theatre the next month. For numerous other special screenings, Gance and his distributors continually revised the film. This unsystematic process of exhibition blurred the distinctions between “Opéra” and “Apollo” prints, and much material was lost or excised without the film ever receiving a general release.

Not helped by the instability of its material body, contemporary critics were rather bewildered by Gance’s creation. Napoléon was praised as one of the boldest formal experiments in modern art, and recognized as being filled with extraordinary images. However, there were numerous objections to its melodrama, to its (mis)treatment of history, and to its romanticism. Léon Moussinac condemned the film’s hero as “a Bonaparte for nascent fascists”, and Vuillermoz said that Gance would be reviled by the mothers of children who would die fighting future wars.

Such suspicion does an injustice to the historical Napoleon and to the ambiguity of Gance’s film. His young Bonaparte is not yet the Emperor Napoleon, a figure who will be corrupted by loyalty to his family and his own hubris. Despite its vast length, Napoléon is only a fragment of the tragic cycle in which the hero becomes villain. Similarly, Gance’s melodramatic elements—particularly Josephine and the fictional Fleuri family—complicate our understanding of Bonaparte, rendering him a more ambivalent and flawed figure than many reviewers suggested. The film’s formal and narrational strategies are also exceedingly rich and subtle. For all the subjective involvement of its camerawork, Napoléon is equally adept at cautioning spectators that what we see has been lost to time—and that Bonaparte’s mission is doomed to fail. This tension between possibility and destiny is at the heart of the film. Gance enables us to relive the past in the present tense, as if its destination is undecided; yet he also reminds us of the distance between ourselves and the predetermined fate of those on screen.

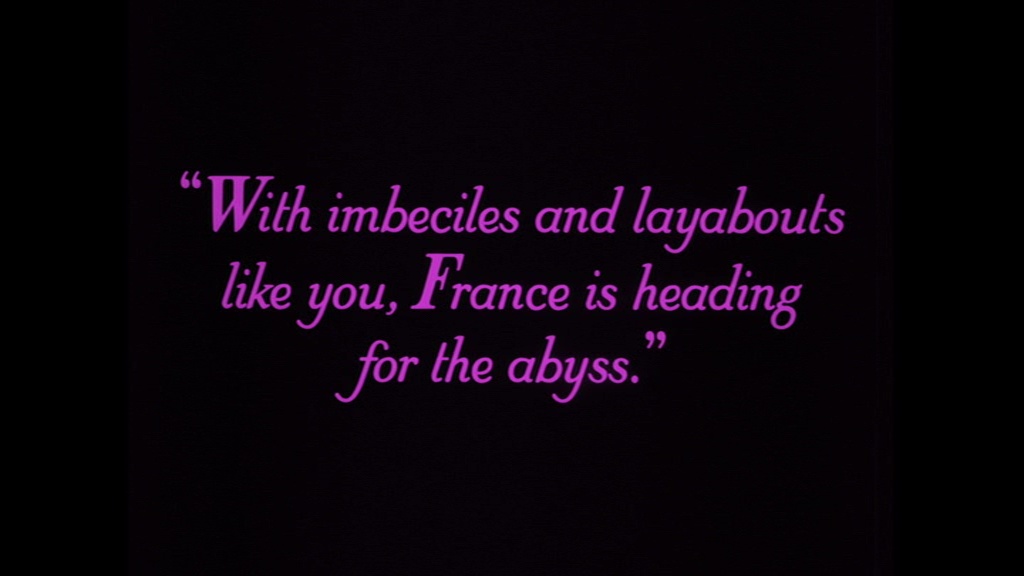

In Napoléon, the conqueror’s stated project is a world without war: he proclaims it his intention to abolish borders and establish the “Universal Republic”. Gance transforms Bonaparte into what he described as a “radioactive” successor to the republican mission begun by Jesus Christ. On screen, Bonaparte is a luminous hero: he thinks in images and transmits light. Yet he also casts darkness: his shadow on the snow of Brienne or the wall of the Convention, his silhouette on the horizons of Corsica or Italy. This secular messiah lives in the shade of his future downfall. For Gance, Napoleon’s ultimate legacy was to inspire generations of artists and thinkers to challenge the status quo. His historical failure revealed new horizons that subsequent generations might pursue. In 1917 Gance imagined a “better future” being brought about by the Great War: a “European Republic”, the realization of which was inevitable. His own political plans in the 1920s sought to redraw the cultural map of Europe, uniting the film industry with the League of Nations and promoting pacifism across the globe. Napoléon was to have been a step on the path to utopia.

Sainte-Hélène (1927-28; unrealized project by Abel Gance)

Aided by his assistant writer Georges Buraud, Gance began drafting Sainte-Hélène in late 1927 and finished the screenplay in September 1928. (It was to have been published as a book in the 1940s, but this never happened. The screenplay remains in the archives.) Originally called “The Fallen Eagle”, this “Cinematic Tragedy in Three Parts” follows the Emperor’s career from the aftermath of his defeat at Waterloo in June 1815 to his death on St Helena in May 1821. This final film was to contrast the huge scale of Bonaparte’s life and ambition against the realities of confinement. In the prologue of Napoléon, we witness the child Bonaparte gaze fixedly at his destiny; in Sainte-Hélène, we were to see the adult perish on this “little island, lost in the ocean”.

Gance was keen to emphasize the historical accuracy of the scenario: “All titles, without exception, are authentic and cover various aspects of life on St Helena. The author insists on the importance of this authenticity, which confers a profound truth to the simplest details.” In his “directive” for the film, Gance explains that “Sainte-Hélène is conceived like a familiar, realist poem in a colossal style. It’s a kind of titanic bourgeois drama”:

The whole tragedy of St Helena resides not in dramatic entanglements, but within the quotidian details and their expression through the figure of Napoleon—a man who is suddenly obliged to come to terms with a base, petty reality which persistently frustrates his genius. He is the open-winged Albatross in a tiny cage. / We wanted to follow the exact events; the rigorous documentation which was used to construct these pages of history will ensure that the spectators will see nothing which did not genuinely happen. Let us repeat: this requirement of respecting the absolute truth removes us from the dramatic intrigues of an ordinary film; through our approach, along the lines of Russian cinema, we have achieved an immense day-by-day reportage of this greatest of historical tragedies. / Our more sober and direct formula must yield much more powerful results than the artificial baggage of typical dramas. Here, the accumulation of real-life details gradually constructs a gigantic drama without the writer having to intervene to arrange them.

However, as with Napoléon, the screenplay of Sainte-Hélène frequently transcends the austerity of any historical remit. Having envisioned the film with a synchronized musical score and sound effects, Gance’s directions for audio-visual rhythm demonstrate the screenplay’s competing tendencies between realist detail and symbolic rhetoric: “The whole film will have to be orchestrated by the Ocean. I think that for the musical orchestration […] it will be necessary to use the noise of the sea as an essential, dynamic, and frightening component—with its lulls, its rages, and its sobs.”

This oceanic “orchestration” of the film is immediately apparent in Gance’s description of the opening sequence:

Open on the swelling high sea. The camera itself is being tossed by the waves. / Dissolve, holding the fluid waves over a map which seems to emerge from their centre: the map of Corsica, then the map of the Isle of Elba, then the map of St Helena. / Very slow dissolve on the head of Napoleon, filling the whole screen with fluids: the ocean and the three maps dissolve into one another. The legendary outline of the small hat; his impassive figure, like marble; a God staring into the beyond. All around, enormous waves seem to roll onto the spectators; the camera itself is always subject to the waves. / Dissolve onto the gigantic stern of the Northumberland, which splits the deep. One can read the name [of the ship]: ‘Northumberland’. Michaelangelo-esque movement of the waves. Across the black stern now appears Napoleon’s writing, which another dissolve makes readable: / ‘I hereby solemnly protest, in the face of heaven and man, against the violation of my most sacred rights, in forcibly disposing my person and my liberty.’ / Dissolve to the stern, and panorama of the top of the stern. / There, one sees only Napoleon—tiny, motionless, silhouetted in black against a stormy sky. / Slow fade.

Sainte-Hélène thus begins by setting the dark silhouette of Napoleon against the spectacle of nature: this vision of the defeated adult fulfils the premonition of the child’s shadow seen at Brienne. Gance contrasts Napoleon’s fall with the rise of the restored monarchy: whilst King Louis XVIII is mocked by his subjects, the former Emperor is surrounded by the ocean’s “titanic waves”. The fluid and uncertain temporal setting of the film’s opening is heightened by a series of flashbacks: the audience was to see visions of Waterloo; of Napoleon’s final abdication; of reprimands against those who had betrayed the royalist cause; of Napoleon’s absent mother, wife, and son. On board the Northumberland, Napoleon wakes up: just as the audience might doubt the reality of the preceding footage, so the character is momentarily unaware of his surroundings. He thinks he is at home in the Tuileries palace, but a series of “aural hallucinations” from beyond Napoleon’s cabin disrupts his illusion: the ship has docked at St Helena.

When Napoleon arrives in October 1815, he is forced to stay on the estate of the Balcombe family whilst his permanent residence, Longwood House, is being prepared. The surroundings were to be profoundly mournful, the Emperor’s solemn face superimposed over a sequence of desolate views. This was to recall the lyrical images of the young Bonaparte arriving home in Napoleon—a point Gance himself notes: “Make a parallel to what I did for Corsica in my first film”. A vital aspect of Sainte-Hélène was to be the use of landscape and location photography: the eerie setting of Napoleon’s last years transforms a naturalist mise-en-scène into a symbolic drama of emptiness and isolation. As with the final half of La Roue (1922), where lyrical location photography makes the clouds and mountainscapes the site of spiritual transcendence, Gance wanted to use the geography of St Helena to create a similarly elevated atmosphere for Napoleon’s Golgotha.

As with Napoléon, comedic episodes provide ironic counterpoint to the tragic course of Sainte-Hélène. Napoleon’s relationship with the Balcombes’ young daughter, Betsy, provides a touching mix of humour and pathos. In one scene, Napoleon plays the monster:

Betsy is in a tree, making fun of the monstrous ‘Boney’. Suddenly, she hears a branch break and a fearful voice issue from the unknown: / ‘What is the capital of France?’ / ‘Paris.’ / ‘What is the capital of Russia?’ / ‘St Petersburg now; it used to be Moscow.’ / ‘What happened to Moscow?’ / ‘It burned down.’ / ‘Who burned Moscow?’ / ‘Bo—…uh, maybe the Russians… I don’t know…’ / ‘I burned Moscow!’ bellows Napoleon, in a terrible voice.

Napoleon then leaps out and grabs Betsy by the hair, laughing as he chases her around. Gance notes to emphasize the “enormous buffoonery, the fundamental ingenuity” of Napoleon and the “sad irony of the scene”:

Here must appear one of the film’s essential themes: the imprisoned force within Napoléon which wants to break out, the playful demon, the diabolic mischievousness—the rustic Italian who conquered the world, who carries in his blood the ‘commedia del’arte’ and a love for marionette theatre. This will soon develop into the tragic.

(This scene is taken from Betsy Balcombes’ published memoirs. See how much more interesting, inventive, and significant Gance’s scene is here than the equivalent in Ridley Scott’s 2023 biopic. In the latter, the “sad irony” and disturbing playfulness at the heart of the scene is not emphasized at all.)

Napoleon and his remaining supporters—Generals Montholon and Bertrand, and their families—move into the damp, mouldy accommodation at Longwood. Upon his arrival, the Emperor is greeted by a large rat, with which he exchanges a lengthy stare. The next arrival is Hudson Lowe, the man in charge of the Emperor’s confinement. “General Buonaparte?” the Englishman asks, echoing the numerous references to Napoleon’s Italian name and accent in Gance’s first film. The small-minded Lowe was a famously poor choice for governor of Longwood, and much of Sainte-Hélène develops out of the friction between the two men—minor incidents take on huge significance in the petty struggles of everyday activity. Gance’s screenplay outlines the ensuing drama:

All the great evils, the vultures of exile, will swoop down on this rock and gnaw at the flank of Prometheus: poverty, dissension, loneliness, boredom, paternal suffering. Time after time, Napoleon’s soul will be visited by these tragic spectres; one day […] they will form a circle around it, like lemurs around Faust’s corpse, gathering together during the five years of terrible agony. However, the hero’s soul will surmount them; it will transcend suffering, transcend men; after fighting against them, it will cross Fire, Water, Air, and arrive at the supreme conquests of the spirit purified by death.

Sainte-Hélène was not only a drama about the isolated fate of its central protagonist but a reflection on wider historiographic narratives. Gance’s screenplay for this final episode consciously revisits and reworks ideas from his 1927 film—completing the cyclical structure of his biography. InNapoleon, the child must listen to the geography teacher insult his native Corsica; in Sainte-Hélène, the exiled adult is forced to take English lessons. Whilst conjugating simple phrases, the name of Napoleon’s jailer unconsciously enters his prose: “I lowe my country, you lowe your country, we lowe our country”. Just as at school, his writing is controlled by the cultural guardians of the old order: Longwood is another Brienne College. The fallen emperor decides to stage a marionette show for the local children, which gives him a chance to narrate his own life. Gance’s intriguing sequence was to be accompanied by the music of Charles Gounod’s comically macabre Marche funèbre d’une marionnette and would feature elaborate stencil tinting to evoke early nineteenth-century chromolithograph prints of Napoleonic battles. The show consists of Napoleon recreating his historical career in miniature but ends with an account of his own death—a disturbing self-acknowledgement of his fate.

In later scenes of Sainte-Hélène, Napoleon and his Polish aide, Pionkowski, plot their escape from the island to forge a new empire in Mexico or South America—fantasizing about the kind of future Louis Geoffroy’s apocryphal history would elaborate in the 1830s. Gance’s screenplay proceeds to emphasize the void between these dreams and Napoleon’s real position: bouts of illness make the exile increasingly immobile, whilst the physical environment of Longwood itself begins to disintegrate. Napoleon can only recall a lost past or envision impossible future realities—he is unaware that his real legacy is being shaped beyond St Helena. Gance lists a series of scenes in which we see statues of Napoleon selling in England, European authors taking inspiration in their work from the exile, and children tracing his name in the stars.

The final scenes of Sainte-Hélène are amongst the most extraordinary in Gance’s vast collection of unrealized projects, and offer the best evidence of his interpretation of the Napoleonic inheritance. Hudson Lowe systematically expels those closest to the exile—each departing friend “comes to hammer his nail into Napoleon’s crucified soul”. An English doctor arrives at Longwood and his prescription of purges and inactivity sees the health of Napoleon rapidly decline. Finally confined to his bed, Napoleon has a series of feverish visions that Gance planned to intercut with details of his surroundings:

Napoleon speaks to the shades of the Revolution around his bed. Cromwell, Washington, Danton, and Robespierre are present. Their unfathomable gaze reveals the heavens above him, filled with heroes and ideas. / Cromwell leans over and wipes the sweat from his brow […] / The rats now control Longwood. Fear reigns. No one tries to drive them out. They pullulate. They take joyous delight in gnawing away amid their filth. Save for the kitchens and the Emperor’s apartment, where the inhabitants now shelter, they have invaded everywhere. We can see them swarming even in the Emperor’s boots, where they have made a fortress. / In contrast: a view of the island of St Helena, like the altar of a dying God. Marvellous vision, as in [the paintings of Arnold] Böcklin. A basalt island of blackest marble like an Acropolis or a Calvary in the middle of a silvered, nocturnal sea […] ‘The waves illuminate the night by the so-called light-of-the-sea, a light produced by the myriads of mating insects, electrified by storms, lighting on the surface of the abyss the illuminations of a universal wedding. The shadow of the island, obscure and fixed, rests in the midst of a seething expanse of diamonds’ (Chateaubriand).

Napoleon cries out to his dead generals, deliriously dictating orders to phantom armies. As the storm wind blows open the window, we were to see a surreal “Tableau of Rats”—a “ferocious” rodent legion that “dances during [Napoleon’s] agony”. Amongst these groups, “a solitary rat performs a comic, macabre step”; in a series of close-ups, we see innumerable “gleaming little eyes and large whiskers”. Gance’s final direction for the scene is to show the “general Sabbath of the Rats”—an astonishing image that makes you wonder how it would be realized cinematically. Equally ambitious is his description of the Emperor’s delirium: “The clock beats. Time dances over Napoleon’s deathbed”; the dying man vomits and “an acrid, black fluid floods over his sheets”; in superimposition, “a Hindu god—Shiva the destroyer—in a hideous laughing mask, with multiple arms, dances”.

As these nightmarish interior scenes become increasingly fervid, the exteriors around St Helena grow more violent:

The sea mounts an assault on the isle; terrible waves seem to want to climb the granite cliffs; the whole ocean rises to see Prometheus die. Strange shadows brood over the plateau and on the mountainsides. Inland, the wind blows in scalding flurries. (Create the perfect synchronism of the wind and the sea in the orchestra with the crescendo of images.) / Title: ‘The End’. / Sky. Sea. Napoleon immobile. The grasping form of a black tree. Napoleon is on his back, as if looking at the horizon of the ocean. Absolute immobility: a tableau synthesizing the futility of all effort and human desolation.

The Emperor has visions of his son, of Joséphine, and of his mother. Finally, he says his last words: “Tête… d’armée…”

The vision materializes—seeming to leave his lips, the head of a giant column carrying tricolours and singing: the eternal Republic is leaving this soul to go and conquer the world until the end of time; and this sigh of divine breath brings forth the impression of a radiant fresco, of a free and colossal force singing a Beethovian march. We see the vaporous column of thousands of soldiers and their heroic laughter, erasing behind it the dying man’s fading lips. And now a kind of apotheosis, evoking the triumph of liberated humanity, a heroic march: that of Beethoven, Schiller, Schubert—and Napoleon. Over an immense frontage this radiant crowd spreads out and advances: men, youths, women, children—their eyes filled with light and courage, a march of power and joy, which sings. (Both images and orchestra must possess the rhythm and theme of Beethoven’s heroic march from the finale of the Ninth Symphony.) / Suddenly an absolute silence fills our ears and eyes—everything dies away. And slowly the image of the mask of Napoleon’s motionless profile is formed, the corner of his lips drawn tight. / He is no more. / (At the moment this image appears, a terrifying bolt of lightning shatters the silence.)

In Gance’s next sequence, the spirits of soldiers from the Empire march alongside Danton, Marat, and Robespierre. Amid “a symphony of flames”, this huge procession advances across the horizon towards Europe “to take possession of human imagination for all eternity”. There follows a “Vision of the Apocalypse” on the horizon of the ocean: the ghosts of kings rise up to bar Bonaparte’s army of the Revolution but are defeated and evaporate in the clouds. The sun rises over a calm ocean: “Smiling, Napoleon and the Revolution pass”. The Napoleonic legend is spread in France and “across the most remote regions of the world”. This “gracious and heroic flight of ideas” inspires “the opening of souls” around the earth:

The children of the Revolution, the sons of the Emperor, spread themselves throughout the universe and take root wherever they land. Entering each house and each heart, they overturn human consciences. Each home is inundated with light and happiness; each inhabitant becomes more courageous and prouder of being alive […] Thanks to this miraculous elixir, selfhood is supplanted by a united humanity. Each heart is made braver and more luminous; each conscience more liberal, more just, more fraternal. / Across the farthest reaches of the globe, they live and inspire Love; they have won over the Earth forever. From the oldest to the youngest, men, women, and children: the whole world sings. / The legend of Napoleon has begun in the imagination of mankind.

In Napoléon, Bonaparte promises that the “Universal Republic” will eventually be created “without cannon and without bayonet”; the final vision of Sainte-Hélène suggests that the spiritual revolution will realize what the material upheavals of the Napoleonic era failed to achieve. Many historians (especially in France) argue that Napoleon’s social legacy has proved to be as permanent as his military achievements were ephemeral. The legislative code formed during his reign was a model of tolerance and is still the basis of much European and international civil law. It’s a very rare example of a document that has genuinely influenced the whole world. (Napoleon himself observed that his civil code would have infinitely more impact than any of his battles.) Gance’s Sainte-Hélène emphasizes the fact that Napoleon possessed an international appeal in his fight against the oppressive hierarchy of monarchies and absolutism. He was seen as a catalyst of change by generations of aspiring reformists, and his legacy inspired innumerable liberal causes in the decades after his fall.

The ending of Sainte-Hélène allows Napoleonic enthusiasm to escape the confines of a historically determined narrative: the vision Gance offers is of a future whose outcome has yet to be decided. After his death, Napoleon is no longer a source of conflict and contradiction within the world—his achievements can now provide inspiration for a new century. These issues are foregrounded in the epilogue to Sainte-Hélène, which Gance sets at Les Invalides in the 1920s. In an eerily lit close-up, we see Napoleon’s final resting place. His spirit “leaves his tomb” and passes unnoticed through groups of tourists who are talking about him. Napoleon’s shade goes to the Arc de Triomphe and visits the tomb of the “Unknown Soldier”, where the remains of an unidentified Frenchman killed during the Great War were interred on Armistice Day, 1920. Afterwards, the Emperor’s spirit returns along the Champs Elysées and re-enters his sepulchre; the films ends as “the great Shadow fades away”.

Whether in the form of personal loyalty to lost lovers or national fealty to fallen comrades, the afterlife of the dead is a recurring feature in Gance’s films. Cinema becomes the ultimate site of reconciliation between the past and the present; in Sainte-Hélène, the ghost of Napoleon acknowledges the sacrifices of the twentieth century—just as, in life, he had promised the ghosts of the Convention that he would fulfil their mission. By resurrecting Napoleon after the Great War, Gance calls for a renewed spirit of internationalism through the legacy of the French Revolution.

(As a footnote to the above, Gance sold his screenplay to the director Lupu Pick, a man he had auditioned for the older Napoleon in 1924. In Germany, Pick and Willy Haas adapted Gance’s screenplay as Napoleon auf St. Helena, which was released in 1929, starring Werner Krauss as Napoleon. It’s a perfectly decent film, but one that limits its own horizons to that of a chamber piece without spiritual dimensions. Ultimately, Gance’s screenplay offers a more cinematic experience than Pick’s film—it’s a perfect example of an incomplete fragment evoking more than a realized whole. As Hans Sahl wrote in 1929: “if you were to choose between Abel Gance and Pick, between the film as costume theatre and the film as a spiritual experience, the decision is not difficult.”)

Napoléon Bonaparte (1935; Fr.; Abel Gance)

Gance returned to his Napoleonic project in 1934. The director added new sound sequences to the footage he had shot nine years earlier, and used many of the original cast to synchronize their voices with the pre-recorded performances. By relying primarily on existing material, Gance found a more economical way of producing a “new” film—and (through dubbing) simplified the task of “orchestrating” audio-visual layers.

Napoléon Bonaparte is set in March 1815, when a group of followers loyal to the exiled Emperor gather in a popular printing press. Surrounded by images of the lost Empire, they relive moments from Bonaparte’s rise to power with the aid of a magic lantern—and these flashbacks consist of scenes from Gance’s 1927 film. The contrast between old and new modes of audio-visual address is particularly evident in the Cordeliers sequence, in which the on-screen performance of “La Marseillaise” is synchronized with a sound recording of soloists and chorus. Though most of the 1935 montage is taken from the footage of 1927, Gance inserts one significant new scene. This consists of a single shot, mimicking the view from a balcony within the church. On the right of frame, we see a small group of sans-culottes; the background of the image is occupied by a back-projected long shot taken from the silent version. A man on the right of frame turns almost directly to the camera and cries out: “What about you? Are you deaf? You can’t sing with us? Well, come on! Sing!” It is a startling disruption of what is otherwise a continuous section of footage from 1927. Gance allows his characters to address the audience, encouraging their participation in the events on screen. (He had also wanted to show the film with “perspective sound”, where sound-effects emerged from different speakers placed around the cinema. It was a precursor to surround-sound decades later, but never made a commercial reality.)

Despite such moments of intensity, the aesthetics of Napoléon Bonaparte too often distract the viewer. The conflation of silent and sound material causes a continual disjunction of space and time. The silent Napoléon was filmed at a camera speed of between 18 and 20 frames-per-second, whilst material from 1935 was shot at 24 fps (the standardized rate for sound recording). This discrepancy causes fluctuating visual rhythmsin Napoléon Bonaparte, as well as actors having to synchronize different eras of performance by speeding-up their delivery. Direct-recorded voices from 1935 are slow, stately, and theatrical—but dubbed voices must gabble to keep up with the increased velocity of their incarnations from 1927. This rhythmic oddity is particularly acute when the same actor appears in footage from both periods: though all their scenes are set in the same time, Marat (Antonin Artaud), Robespierre (Edmond van Daële), and Masséna (Philippe Rolla) age ten years in-between shots. The visual condensation of these different layers never overcomes the fundamental problem of their aesthetic difference: the figures of 1935 struggle to involve themselves with the action of 1927. In a new scene near the end of the film, Masséna and Bonaparte perch awkwardly on the right of frame, peering at a back-projected image on the left that shows cavalry charging across the Italian landscape. Rather than encouraging the audience to thrill in the prospect of action, Gance (unintentionally) imbues the spectacle with pathos. These actors are looking back at their youthful comrades, failing to maintain the pretence of being in step with cinematic continuity. It is as if the characters were themselves viewing Gance’s silent work as the source of participatory action—and longing for its return.

Aesthetically and narratively, Napoléon Bonaparte is concerned with this distance between the creativity of the past and the reproduction of the present. The film’s setting within a print works is deeply significant. The characters are surrounded by huge two-dimensional illustrations of battles, and old veterans stand next to life-size reproductions of their young selves. Their situation mirrors that of the film: old and new footage is juxtaposed, past and present are made to interact. Similarly, Gance’s use of vertical wipes to transit between live-action and still images is reminiscent of how glass slides overlap during an illustrated lecture. It affirms the link between fictional and real spectators: for audiences of 1935, Napoléon Bonaparte has the same function as the magic lantern for the on-screen audience of 1815. This subtle means of connection is evocative, but the effect is very different to the kind of connection established in the silent Napoléon. The sound film’s characters are witnesses, not participants; they reflect on the lost ideal of a living past, consuming mass-produced images in the hope that their content will one day be reanimated. By so cleverly mirroring 1815 with 1935, Gance isolates the real audience as well as the fictional one.

Napoléon Bonaparte ends with the arrival of news that the Emperor has returned to France from the island of Elba. Bonaparte himself passes through the streets, but the old, scarred veterans are only able see his silhouette against the wall. They drag themselves in the wake of the general’s gathering army, hoping to rejoin their comrades—but their ancient bodies are unable to sustain them on the march. Years seem to pass and still, they whisper to the camera, Bonaparte is out of reach. In a series of close-ups, Gance shows the last strength drain from these living fossils of previous wars; they fall into silence and stop. A final, lingering close-up of one of their number dissolves into a still image of his face, freezing the man’s movement within the confines of the frame. A second dissolve transforms this still photograph into a charcoal etching of his features—and a third changes this illustration into a sculpture. The camera finally tracks backwards to reveal that the form of the soldier belongs to a relief carved into the side of the Arc de Triomphe. The Napoleonic spirit becomes petrified; we await some future resurrection to lift these bodies from the stone of the monument and allow them to reach their destination. By retrogressing from the moving images of cinema to the static images of plastic art, Gance’s haunting vision draws attention to the fossilization of creative energy. Regretfully, the use of sound throughout Napoléon Bonaparte perpetuates this same effect of disengagement: recording technology annuls the power of participatory action found in the silent Napoléon.

Austerlitz (1960; Fr./It/;Yu. Abel Gance).

In the 1950s, Gance wanted to produce another grand Napoleonic project: “D’Austerlitz à Sainte-Hélène”. This would be a counterpart to his 1927 project, an epic filmed with triptych Polyvision. By some miracle, he achieved financial backing through a French-Italian-Yugoslavian co-production and assembled an all-star cast (Pierre Mondy, Martine Carol, Jean Marais, Vittorio De Sica, Michel Simon, Claudia Cardinale, Jack Palance, Orson Welles). Though it did not resemble the scale of his initial conception (it was not shot in Polyvision, nor did the narrative stretch beyond 1805), it was at least released in a version that exceeded the usual temporal dimensions of a commercial film. Though Gance’s biographer Roger Icart suggests that the initial montage was 5500m (approximately 200 minutes), other sources state that the film was originally 4500m, reduced to approximately 4000m for exhibition. (In the UK the film was released in 1965 in a version of 123 minutes. For this, the soundtrack was dubbed into English—among the all-star cast, only Welles retains his own voice.) And unlike so many of Gance’s films, the longest commercial version of the film (4500m, c.170 minutes) survives and looks as good as it can.

The film itself if more interesting thematically than cinematically. By focusing events around Napoleon’s coronation and the battle of Austerlitz is to concentrate on Napoleon’s limitations as a politician and his brilliance as a general. Austerlitz shows us “Bonaparte” becoming “Napoleon”, the republican becoming an imperialist. But the film’s depiction of the coronation is very interesting. Without the budget to show the ceremony, Gance recreates it with puppets. (Cf. that projected scene in Gance’s Sainte-Hélène screenplay.) It’s a good way of showing both the love of the ordinary French people for Napoleon, but also the distance between them. As with the Fleuri family in Napoléon, the crowd becomes isolated from their hero: Bonaparte the man becomes Napoleon the legend. The same idea is in Napoléon Bonaparte, where we only see Napoleon as a shadow—or as a memory, embodied in the footage from the silent film. The crowd in Napoléon Bonaparte watch projected images, just as the people see the puppet coronation in Austerlitz. Napoleon is unreachable, detached from the real people. In Austerlitz, the battle also shows us the glory and the horror of Napoleon’s campaign. (It also offers a fitting climax to the film, a kind of reward for the audience after the first 90 minutes of dialogue!)

Though critics were generally unimpressed, Austerlitz was one of Gance’s biggest commercial success. (A source informs me that three million tickets were sold in French cinemas at the time.) The mere fact that it existed was a kind of victory. It enabled him to maintain a presence in French film and television culture into the 1960s. But as a work of art, I think Gance knew Austerlitz was not as he had envisioned it. The film was notably absent from a list of his most important projects, compiled in 1967 for Kevin Brownlow—implicit acknowledgement that it belonged to those works about which Gance said, “there is no point talking about them. They have no value.” Austerlitz remained only a shadow of what Gance had intended, either in the 1920s or the 1950s.

That said, Austerlitz certainly has more panache than contemporary Napoleonic films like Sacha Guitry’s Napoléon (1955) or King Vidor’s War and Peace (1956). In this context, it is a competent commercial film with much originality. And unlike either Gance’s Napoléon Bonaparte or Bonaparte et la Revolution, Austerlitz is aesthetically coherent. But both these other Gance films are far more interesting attempts to revive his Napoleonic project. Compared to them, Austerlitz is banal in the extreme. And none of these later films can compare to the 1927 Napoléon, or to the best of Gance’s silent work. Austerlitz is also much less interesting than Gance’s unrealized projects of the post-1945 period. Both La Divine tragédie (1947-52) and Le Royaume de la Terre (1955-58) are extraordinary conceptions, but they exist only on paper. On paper, Gance was always imagining grandiose projects. But only early in his career was he able to adequately realize them on screen. By the time of Austerlitz, Gance was thirty years past his prime as a filmmaker.

Bonaparte et la Révolution (1971; Fr.; Abel Gance)

This four-hour film was Gance’s final effort to rework his Napoleonic project for new audiences. As well as using footage from his Napoléon, Napoléon Bonaparte, and Austerlitz, Gance added new live-action material, still photographs, and voiceovers. It is perhaps more rewarding to consider the result of this assembly as a kind of historical documentary about its author’s earlier projects. Posters for his 1971 film announced that it had been “45 years in the making”, and its first sequence is a prologue in which Gance explains the history of his creation. In this monologue, the author directly addresses his film: “Rise up from your tomb—and speak!” This was as much an effort at self-regeneration as it was an attempt at film restoration. Gance was fighting critical oblivion. He told his first biographer, Sophie Daria, that he already believed himself a member of the “living-dead”. In an address at the memorial service for Jean Epstein at Cannes in 1953, he announced: “I too have a mouth filled with earth […] I too have been killed by French cinema; this is one dead man speaking to you about another!”

By 1971, Gance was 45 years older than he had been when he filmed the silent Napoléon—and 55 years older than the historical Saint-Just had been when he died in 1794. Despite this gap, the director insisted on reprising his role. Though the scenes of Thermidor are taken primarily from the 1927 film, new footage shows Saint-Just in silhouette at the end of a dark passageway, supposedly a gallery overlooking the Convention. The camera approaches no further than a mid-shot of the character, but even here the silhouette is clearly that of an elderly man and not a youth. Gance’s age is equally tangible in the timbre of his voice, in spite of the echo effect that is applied to his speech. Whilst the soundtrack seeks to hide the unflattering quality of this direct-recorded sound, the noise of the crowd to which Saint-Just responds is retrospectively dubbed. This sense of dislocation is enhanced when Gance cuts between Saint-Just and the hall: the members of the Convention have bodies from 1927 but voices from 1935 or 1971.

Obscured in shadow and separated from his audience, it is as though Saint-Just is speaking from beyond the grave and seeks to hide his ravaged body from the lens. There is a piquant contrast between Gance’s attempt to give the words of Saint-Just new life and the tentative exhibition of his own corporeal frailty. When his speech from the gallery is finished, Saint-Just turns slowly around and ascends the staircase towards the camera. His silhouette looms closer and closer to the lens, until it blocks our view entirely. Gance’s next cut takes us from 1971 to 1927, whilst the soundtrack takes us from 1971 to 1935. When we see Saint-Just enter the Convention, the painful slowness of his gait visible in the previous scene has gone—he now walks with faster-than-life agility. From his reticent position in the shadows of the gallery, Saint-Just’s youthful frame and bearing have been magically restored, his face is revealed in a fully-lit close-up, and his voice is piercingly alacritous. This extraordinarily bizarre sequence is potent evidence of Gance’s refusal to let the material constraints of reality interfere with his personal vision.

Throughout, Bonaparte et la Révolution attempts to defy the dispersive effects of time. By seeking to reconcile past and present, Gance’s 1971 film compounds all the manifold problems of asynchronism evident in Napoléon Bonaparte. Actors age several decades between shots, or else rediscover their youth in a fraction of a second. Every aspect of filmstock, photography, lighting, sound balance, and performance style is in riotous disagreement. Gance’s use of static illustrations and still photographs places further disjunctions within the visual rhythm—and makes the juxtaposition of different media even more disconcerting. Whilst live-action material dates from anywhere between 1927 and 1971, Gance’s illustrations and still photographs have a historical range between 1789 and 1971. Rather than being a coherent or self-sustained work, Bonaparte et la Révolution is a palimpsest that muddles together all of Gance’s earlier projects. In 1971, this once masterful editor was apparently impervious to the problems of textual compatibility: every seam and stitch is horribly visible.

Nearly half a century after the fact, it was a prodigious feat to find words for the mute lips of 1927. Yet the very efforts taken to reconcile material from contrasting eras only serve to accentuate their difference. Though the film makes every effort is deny it, the truth is that the author of Bonaparte et la Révolution is exiled from his text by dint of time. The aesthetics of 1971 cannot be reconciled with those of 1927 or 1935, just as the Abel Gance of 1971 cannot be the Abel Gance of 1927. The author’s first and last Napoleonic films are entirely different beasts: their conception and realization are separated by a whole lifetime. Bonaparte et la Révolution is a museum that preserves the remains of its previous incarnations—it is a work which can but speak of history and of itself in the past tense.

Paul Cuff

Some of the above contains material I first wrote in the following publications (see also the About Me page):

– A Revolution for the Screen: Abel Gance’s ‘Napoléon’ (Amsterdam: Amsterdam UP, 2015).

– ‘Living History’, Liner notes for Napoleon (1927) [DVD], UK: British Film Institute, 2016.

– ‘Presenting the past: Abel Gance’s Napoléon (1927), from live projection to digital reproduction’, Kinétraces Editions 2 (2017): 120-42. [Online version.]