Filmarchiv Austria produces a number of DVDs (and, latterly, Blu-rays), and one series of releases goes under the name of “CinemaSessions”. These editions combine rare archival prints with new soundtracks, usually experimental/electronic. In the third release of this series, we are given a 40-minute programme of short films and fragments that share the themes of fire and colour; the soundtrack was performed/recorded live in 2011 by Peter Rehberg.

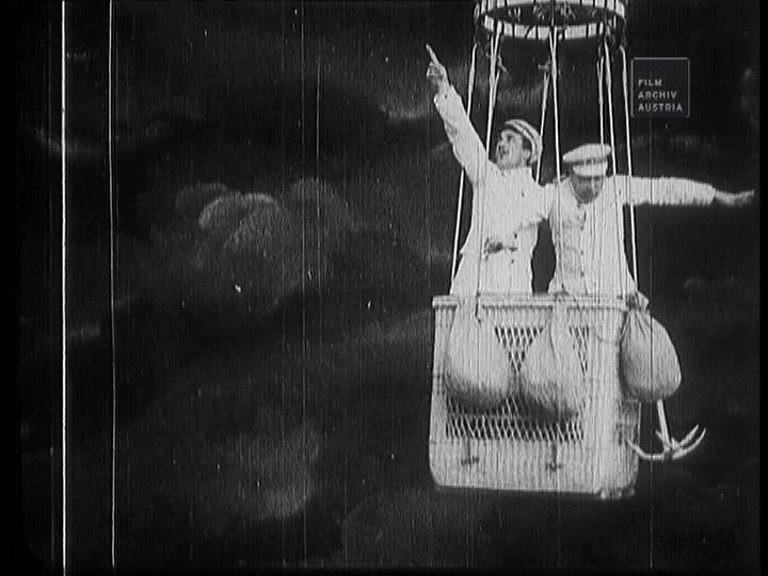

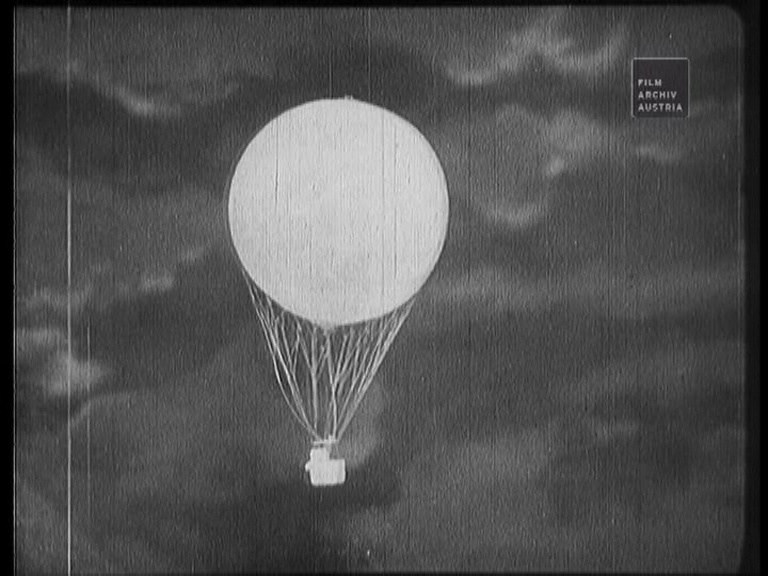

Un Drame dans les aires (1904; Fr.; Gaston Velle)

The film starts with footage of an actual balloon gently rising from the ground. But instantly we cut to a studio backdrop of stationary clouds, before which two bright officers in too bright costumes scan with their telescope the non-existent world below. Cutaways to irised views of the sea, to an anonymous cityscape. But lightning flashes across the sky (or at least, a scratched bolt across the celluloid) and rain pours down. Reality changes. Gone are the human crew. Now a model floats up, moving wildly, is cut in half by a bolt. The screen erupts with fuscia-red blooms. (How quickly things escalate and fall!) The balloon tumbles into the sea, which becomes real—or real water, at least, in a real tank, against a makeshift backdrop. And the film goes to the trouble of washing itself with a blue tint, so we feel a little of the cold and the shock and the aura of this unlocatable sea. A rower desperately pulls the two survivors from the water. The film is very short, and disaster occurs very suddenly. Such are the bizarre shifts in tone and form between shots that anything at all might happen next. The film could be of any length, could open and follow any narrative possibility.

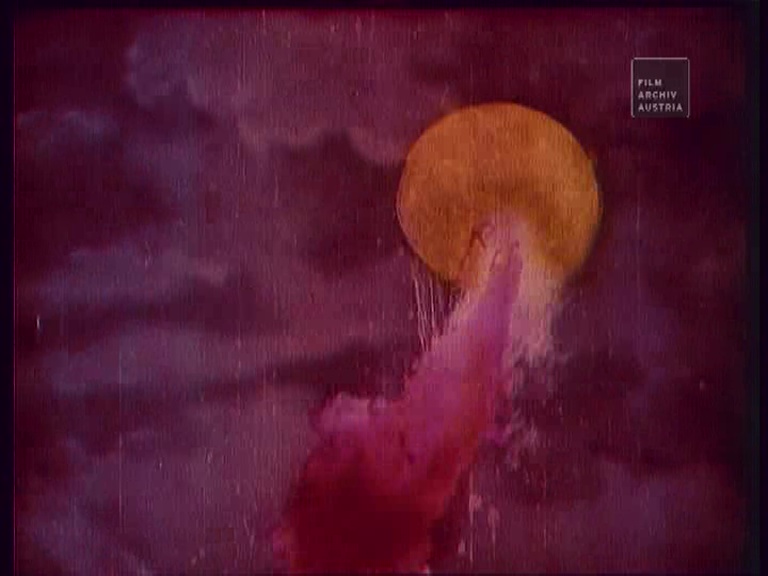

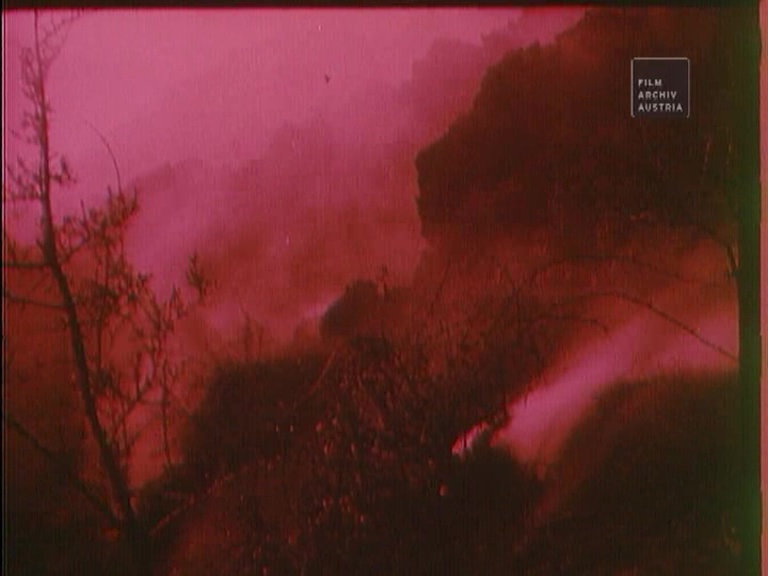

L’eruzione dell’Etna (1910; It.; Socièta Anonima Ambrosio)

The world is a fug of noxious red. When it’s dark it’s a bloody coagulate. When the sky registers enough light, it’s a violent magenta. Colour soaks into the rocks, into the soil. Little dashes and specks of people provide scale, a sense of time. Titles assure us the local populace are “terrified”, but we see them going calmly about their business: cutting and moving trees, or just standing and watching the smouldering spectacle. The 35mm has temporal footprints upon its surface: a run of horizontal lines, white cuts that scurry up the frame. And at the edge, the border of the image looks more like lava, looks more threatening, than anything we see on screen.

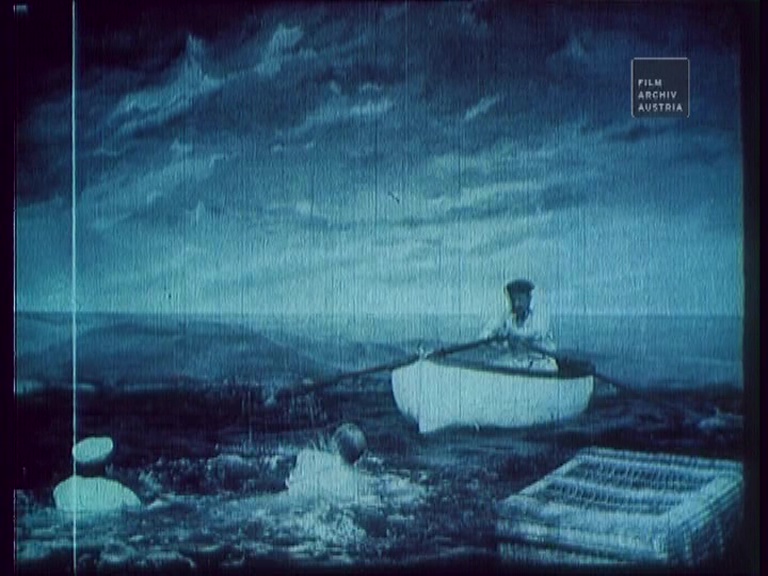

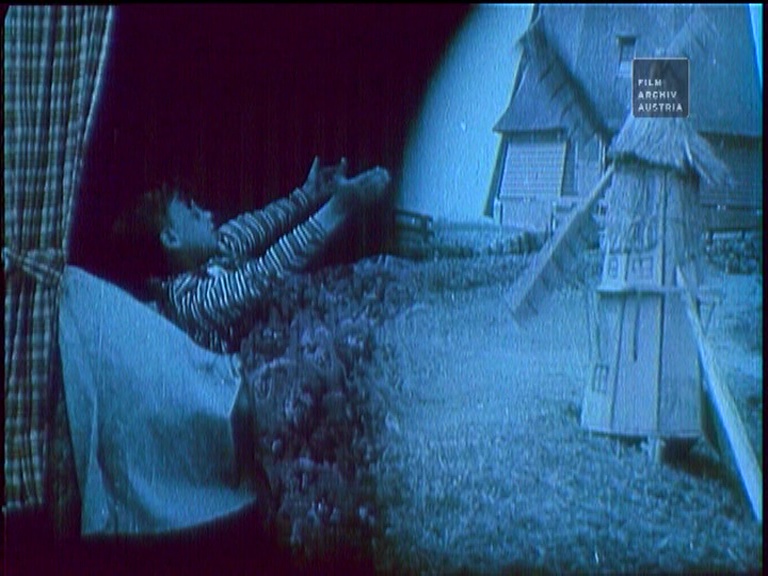

L’Âme des moulins (1912; Nld./Fr.; Alfred Machin)

This film has the intense clarity of a nightmare. The exteriors are crisp. The northern light is cold, acute. It cuts sharp contours of the windmill. The stencilled colours are gentle. They sometimes kid you that reality has been captured honestly, not mimicked in retrospect. Such is the way a nightmare tricks you, by casting a spell in which you might just believe. The story is simple and brutal. A boy builds a model windmill. It’s his joy. In the background is the real windmill where he and his parents live. A beggar approaches. A crutch helps bear his weight. His limp is aggressive, assertive. Unlike the boy and his parents (who wear clogs), the beggar has a peasant’s leggings. He’s a figure not out of a postcard, but out of reality—somewhere beyond the cosy little world of the family. Father and mother turn him away. He tries again. The father knocks him down. The beggar shakes his fist at the windmill, then batters the boy’s windmill—mercilessly upending it, beating it to splinters. The father strikes him again, and once more the beggar raises his fist in threat. It’s an image of unrepentable fury. The film is mute, this world is mute, but that gesture—the arm extended, the fist clenched—is as articulate an expression of rage as we need. Beware this man. In silhouette, in the cold northern light, the beggar sits at a distance. Again, the raising of the arm, the clenching of the fist. Each time, the threat assumes more menace. The boy dreams of his toy windmill, his arms reaching out to the split-screen vision. A sinister visual rhyme with the beggar’s outstretched arm. And a presage of the finale. For the beggar is on his way, a creeping shadow against a supernal sky. The composition here is a touch of genius: both beggar and windmill are part of the same silhouetted plane. It gives the impression of the beggar being larger than the mill itself. The real-size windmill looks as vulnerable as the child’s toy mill. This is a fabulously nightmarish image, with its blue-tone-pink colour pattern. Where toning and tinting overlap, they turn the silhouetted plane deepest purple. The clouds are a glowering violet. And what kind of moon sets this sinister pink? This is a time for nightmares. The beggar is crouching at the base of the windmill. The fire he starts glows the same pink as a distant patch in the sky. No fire is this colour—yet here it is. The interior fills with smoke. The family flees. But the camera watches, and watches, as the windmill is consumed by fire. Now the frame is washed rose-red. Sky and reflected sky are a blank wash of colour. Flames and smoke are reflected in the still canal. The family hold each other, weeping. The composition mirrors that of the beggar, contemplating the mill. That image was blue, this image is red.

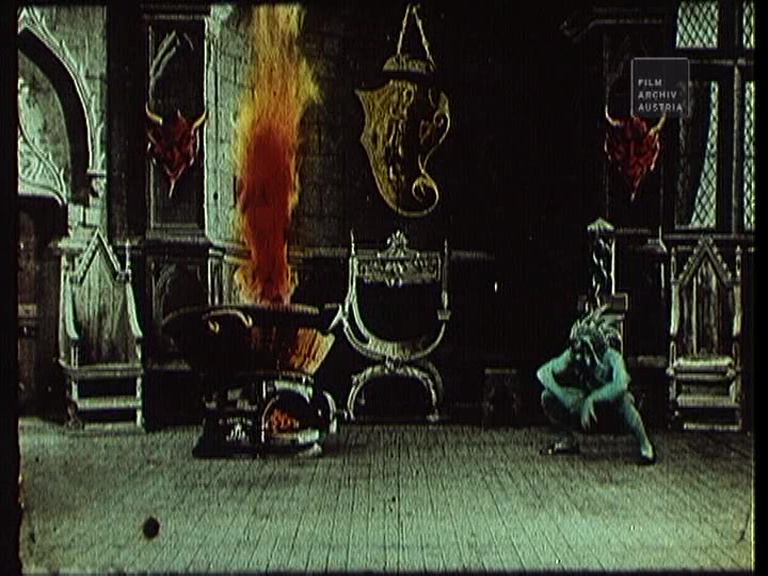

Le Chaudron infernal (1903; Fr.; Georges Méliès)

Two turquoise devils are torturing women. One is bundled into a sheet and tossed into a cauldron. An eruption of red flame. Others are led in, then fed into the vat. The lead devil (Méliès himself, one presumes) capers and cavorts. Is he quite in control of his experiment? In the air above him emerge three pale shapes. These apparitions are impossible to capture with frame-grabs: they are as soft as will-o’-the-wisps, morphing and moving with each frame. The impression they make is only evident when you watch the film itself. The rest of the image is clear, crisp, filled with stage-set lines. But these forms are ethereal, like rags floating in water. They are floating, waving. Do they have wings? Are they souls? wraiths? The devil cowers, scurries back and forth. The angelic forms burst into flame. The devil hurls himself into the cauldron and the film explodes.

La Légende du fantôme (1908; Fr.; Segundo de Chomón)

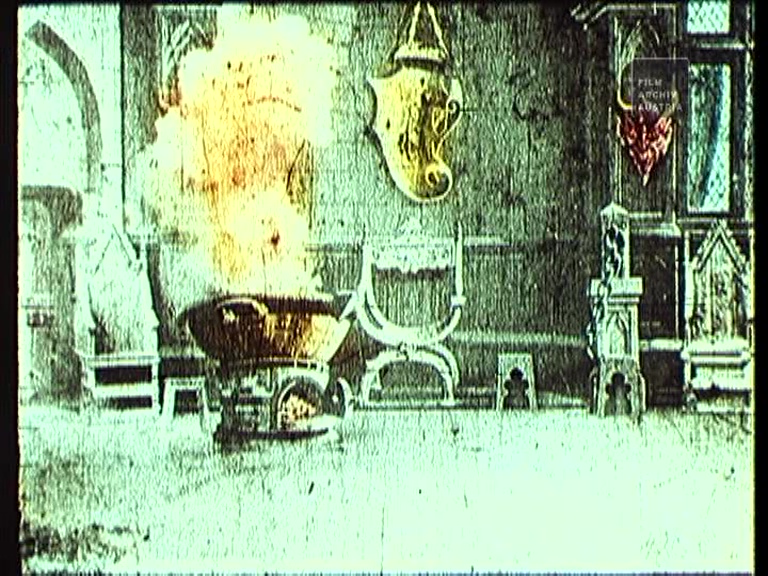

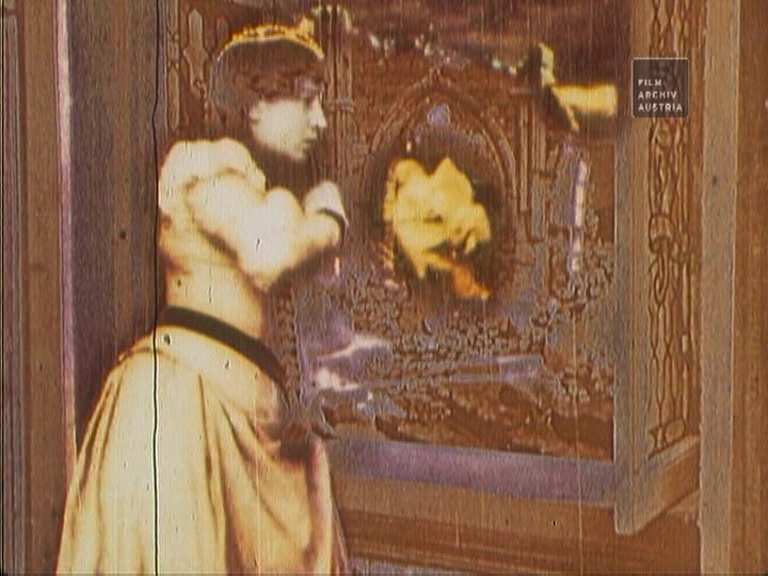

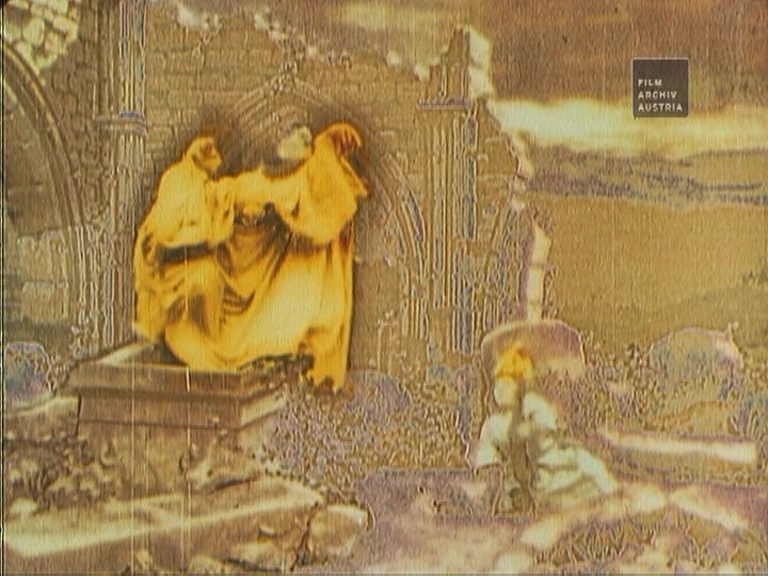

From its very first image, there is something extraordinary about this film. It is in a semi-stable state of decomposition. It is an arrested death, a suspended transformation. Elaborately stencil- and hand-coloured throughout, the different layers of chemical treatment each have deteriorated at different rates, in different ways. Comprehensible figures appear in landscapes of marbled, mottled uncertainty. Parts of the image are positive, others negative. It is uncannily beautiful.

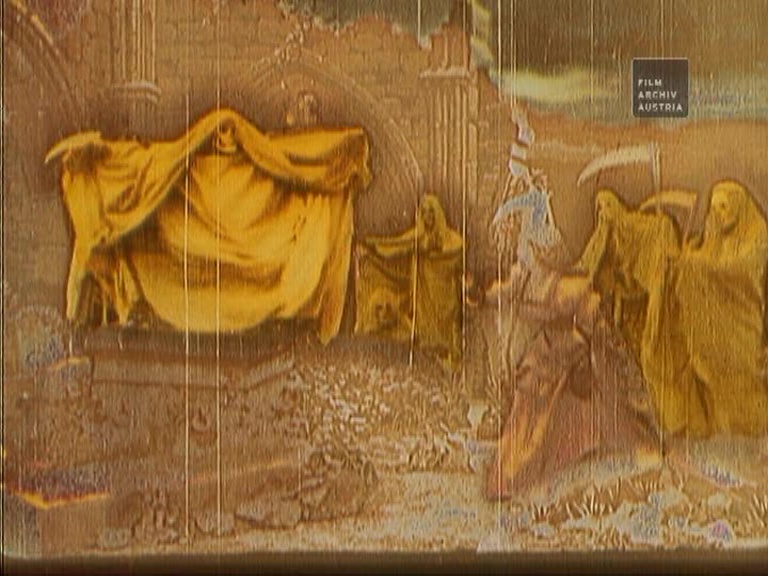

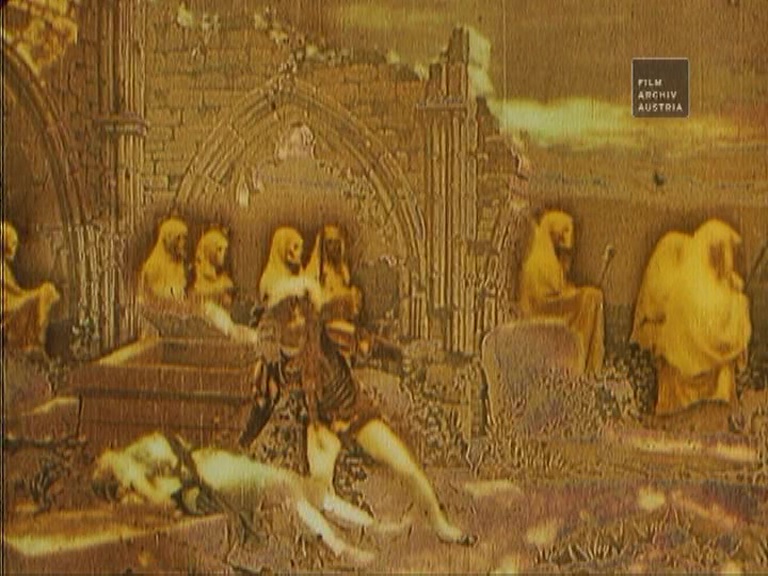

The first shot tests our comprehension. A woman stands at a window. Outside, gothic ruins—and a pale shape fluttering in a halo of darkness. The film skips, leaps. One cannot trust the continuity of such a world. Who is “Zoraida the witch”? Their motto appears: “A thousand years you shall err and be jinxed, you who despised me.” The words are as cryptic and mysterious as the images. In the gothic graveyard, the woman investigates an open tomb. Figures emerge from the background: a dozen grim reapers, the colour of glowing parchment. Dark haloes flutter about their bodies. On stage, such grand guignol ghouls might look ludicrous. But here, in this film, they are majestically creepy. Then a figure of stupendous horror rises from the open tomb. See how the folds of its winding sheets glow sickly gold. And look how it seems to emerge from a different plane of reality. Its tomb is a dim, faded photograph—a photocopy of a photocopy. But the phantom is a burnished, three-dimensional force rising from the centre of the image. (I’m already running out of ways to describe how extraordinary this looks.) The skull-faced phantom—the witch? Zoraida?—issues instructions: “You shall find the devil, challenge and defeat him. He then will hand you the light that cannot be extinguished. Use it to reach the bottom of the sea. Look for the black pearl and return it.” These are lines one might remember from a dream, or a nightmare, words that make no sense outside of the dream itself. The wraiths are transformed into female warriors with winged helmets, glowing gold. The woman herself assumes the mantle of a warrior. In this astonishing film, I now expect nothing less than inexplicable transformations.

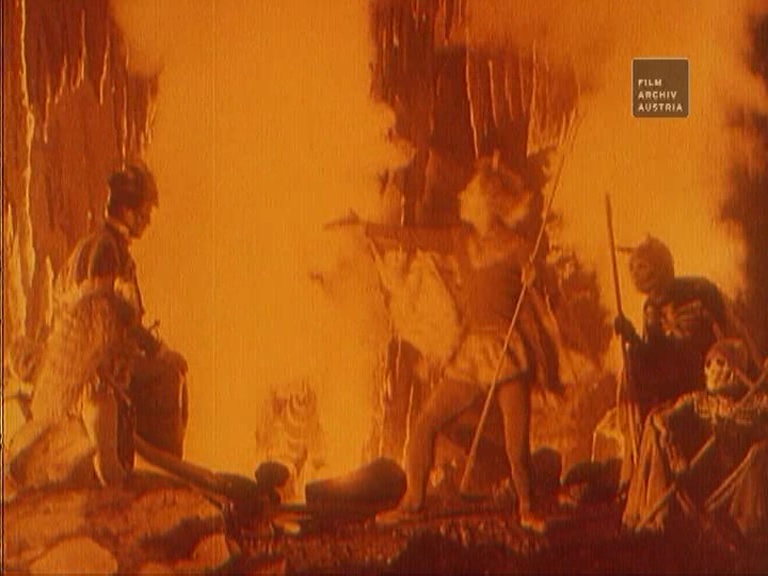

“Satan gathers his forces”. We are in hell. Fire, skulls, pitchforks. A mass of devils, of women with flowing hair. (Hell is both a second-rate Parisian theatre and a first-rate Renaissance painting.) Satan embarks, followed by devils, followed by a train of rather bored-looking women. Inside a waterlogged cave, a moving cavalcade, a carnival of flaming torches. Satan and his posse of women ride a stupendously entertaining vehicle: a Model-T Ford truck transformed into a Louis XIV bedspread. The face of a moustached devil on the front, a sinister rising run at the back, it rumbles forward—surrounded by flare-wielding devils and pretty dancers. Satan lives in a tunnel and emerges in a morphing ball of marmalade-coloured fire. The outside world is a clotting brown, a warped memory of rocks and greenery.

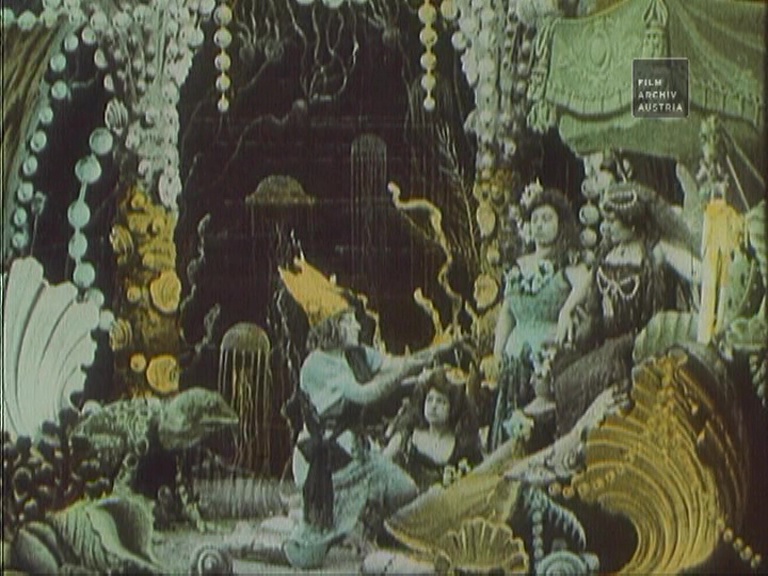

Somehow—and the film has either lost interest in narrative sense, or else there are missing scenes—the woman from the opening scene wins the favours of Satan. She carries in her hands “the light that cannot be extinguished”. At the entrance to another cave. From a smoky maw, a frog leaps forward. He too wears a dark halo that havers about his body. He motions for the warriors to follow him. We are under the sea, surrounded by elaborate cut-out jellyfish, cut-out pearls, cardboard shells. The frog hops in the background. A queen and her female retinue greet the woman. The queen gives the woman the black pearl. The woman flirtatiously thanks her. They embrace, there is a kiss of the hands. It’s disconcertingly flirtatious. Are we to assume the woman has been transformed into a male warrior? There are no answers, for the film becomes a stage-show underwater world: screens rise, part, rise again. Backdrops change and there is a huge parade of creatures, crawling and marching and swimming from either side of the set—and the inevitable line of flowery maidens.

We return to the overworld. Here the film loses a little of its magic, but none of its charm. For the satanic vehicle has lost its majesty: it’s now all too obviously a truck with a bedsheet flung over its carapace. The sheets don’t even cover the front wheels. Perhaps it’s deliberate. Perhaps it was a mistake. (If it was a mistake, imagine how awful for the makers to see it when going through this scene frame-by-frame to colour it!) But now we return to the gothic graveyard. The woman lies before the tomb of the phantom, who emerges in a terrifying bloom of winding sheets. But when the phantom drinks from the black pearl, it is transformed into a man. The transformation is rendered sublime by the decomposition of the colour on the 35mm copy. Here the body of the man is as delicate as tracing paper. His hair and clothes are dreamily soft, but the feather on his hat is strangely sharp. He is a ghost in the effort of attaining solidity. The gothic arches behind him are legible, but he is oddly amorphous. He turns to the camera. What kind of expression is this? No doubt it’s meant to be one of delight, but how can we not be frightened? What kind of power has he harnessed? Was he not a witch just now, a dreadful phantom? Why has the woman given him body? And what of the woman? She lies now beside the open tomb, as the army of grim reapers gathers with flaming torches in the background. What has happened? What happens next? What forces have been unleashed? Is this the triumph of Zoraida? And shouldn’t we be afraid? The film ends.

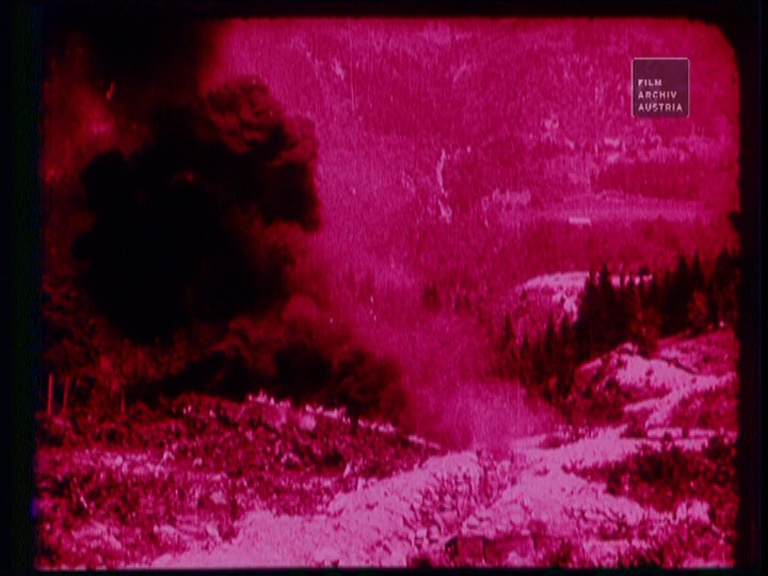

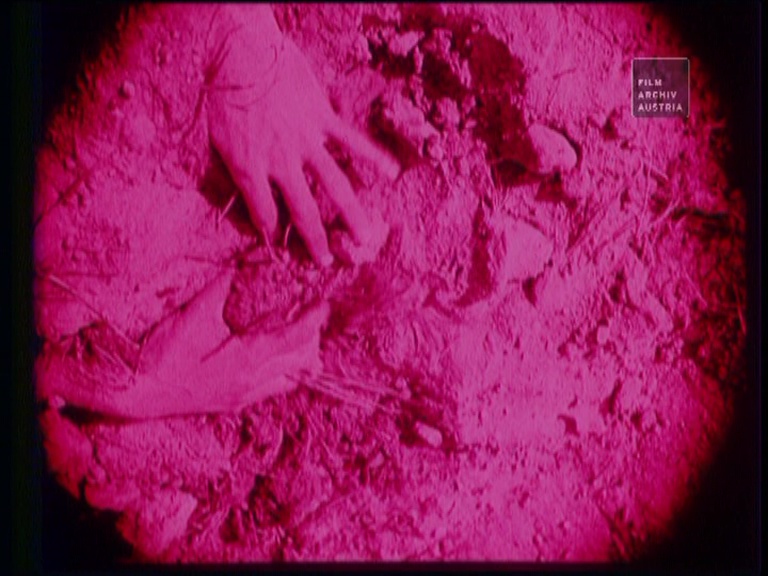

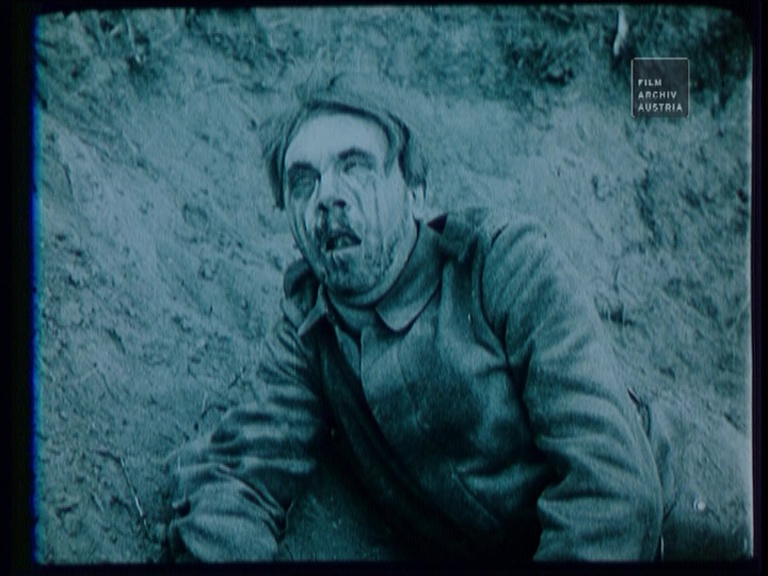

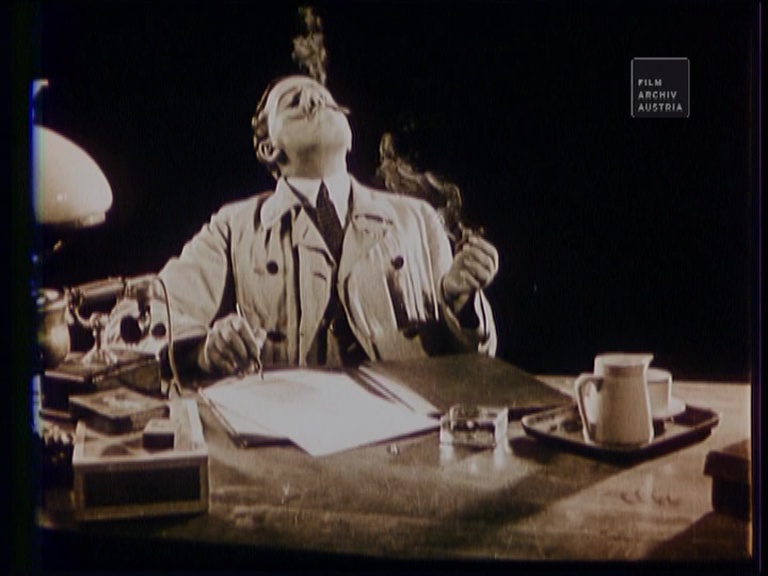

Namenlose Helden (1924; Aut.; Kurt Bernhardt).

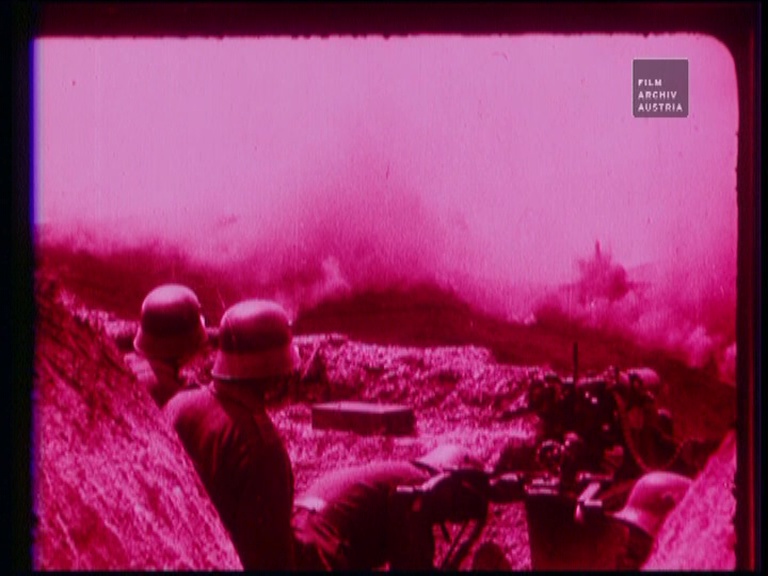

This was once a feature film and is now a peculiar montage of truncated scenes. We see preparations for “the storm”. The footage is taken from newsreels of the Great War. We see planes, airships, enormous guns. A woman stands guard at a barrier, then collapses. Onlookers push past. We see the woman in an unconvincing apartment, badly lit. A doctor stands by, shaking his head. A child stands awkwardly at the edge of frame. The battlefield, another world. A soldier at the frontline. Pink sears the screen. Clouds of gas drift across wasted landscapes. Flamethrowers streak the rubble. Figures from the real world ignore the camera, while the soldier from the fictional film is given extended close-ups. He receives a letter: “Hansel is doing better again, but our dear little Fritz has died of his burns. I am very sick and…” He takes an age to screw up the paper, to scream. The performance is committed, embarrassingly raw. He sees a vision of his son(?), first smiling, then his face covered in burns. The screen shares the searing pink of the battlefield. The man’s tears shine. He is in the battle. The soldiers from the newsreel past advance towards their unseen enemy, long since triumphant. The man is in a shell hole. There is an explosion. Hands grasp at the soil. The next day, the man is the lone survivor: his face covered in streaks of blood, he shouts then collapses. Elsewhere, a writer records the great victory of the battle. Contentedly, he blows a smoke ring. We see the dead of the battlefield. The film ends.

Well, this is a strange and fascinating programme. The first two films are not especially interesting (L’eruzione dell’Etna is less compelling than its title suggests), and the fragments of Namenlose Helden do not suggest a particularly good film. But Le Chaudron infernal has some great effects, and L’Âme des moulins and La Légende du fantôme made a very strong impression on me. Segundo de Chomón does demonic trick-films like no other (not even Méliès), and I found La Légende du fantôme as grippingly strange and compelling as anything I’ve seen from the second decade of cinema. The chemical instability of the images creates an uncanny magic that adds to the film’s appeal. This film was the heart of the programme, and the one film which really justified releasing the compilation on DVD.

In terms of image quality, these films looked good when I saw them on my television screen—but now that I come to go through them on my laptop to get some image captures, they look less so. Many of the films do not survive in the best quality, and the video transfer does them no favours. What’s more, it’s a shame that there is a copyright logo in the top-right of the screen throughout. It spoils the extraordinary visuals of these films, the colour and texture of which are meant to be the main feature of this programme. Is this watermark really necessary? Other films in the series, and titles produced by Filmarchiv Austria more generally, do not have the logo. Why must it appear on this release? It’s something I’d expect to find on videos on the archive’s website, but not on films presented on a commercial DVD. In terms of sound, Peter Rehberg’s electronic music didn’t leave much of an impression on me. It’s not quite sinister enough for some of the films, not light enough for others—and never captures the rhythm of the visuals. But as a wash of electronic sound it’s hardly the worst accompaniment I’ve heard for silent films.

These reservations aside, I did get a lot of pleasure seeing these films. This DVD contains some fabulous curiosities, the images of which will linger in my memory.

Paul Cuff