The final two days of streaming from Bonn provide us with two variety-themed melodramas. The first is more familiar, at least in terms of its cast; the second was a complete surprise, and yet another welcome discovery…

Day 9: Song. Die Liebe eines armen Menschenkindes (1928; Ger./UK; Richard Eichberg). As with Saxophon-Susi on Day 2 of Bonn this year, I found myself in the curious position of having already seen Song – likewise at the (online) Pordenone festival of 2024. As I did last week, I will refer readers interested in Eichberg’s film to my post from that earlier occasion.

In lieu of commentary on the film, I observe in passing that there is a musical connection between Saxophon-Susi and Song: both were originally scored by Paul Dessau in 1928. Though Dessau’s later work (including sound films, orchestral and chamber works, and several operas) is well represented in terms of DVDs and CDs, these two feature film scores do not seem to be extant. As with so much absent silent film music, one wonders if this is a case of genuine loss or simply a case of no-one having been willing or able to look. (The most typical case would be that both films are released on DVD/Blu-ray with a modern substitute, only for Dessau’s scores to be rediscovered and lovingly reconstructed. More typically still, these scores would then be performed just once at a festival I cannot attend and hear about only retrospectively, and forever after remain unavailable due to lack of interest and/or finance for appropriate recordings to be issued with a new home edition. I would then be left with years of regret and frustration, with occasional outbreaks of false hope when a rumoured broadcast recording failed to appear – or one that remained unavailable outside a restricted copyright region of central Europe. Such is often the fate of original orchestral scores, and of those who long most fervently to hear them.)

For the presentation of Song from Bonn this week, Stephen Horne performed on piano (and various other instrumental interpolations) – just as he did for this film at Pordenone. Both iterations were excellent. However, given that the restoration and musical score were from the same sources, I merely dipped in to this presentation from Bonn, finding myself (as before) marvelling at how nice the film looked – but remaining just as ungrabbed by the characters or drama. Not without some guilt, nor without regret at once more not seeing this with an audience, I skipped the rest for the sake of time.

Day 10: Sensation im Wintergarten (1929; Ger.; Gennaro Righelli). The circus acrobat “Frattani” (Paul Richter) returns to Germany after many years abroad. His real identity is Count Paul Mensdorf, and as a child he ran away from home to avoid his new father, the Baron von Mallock (Gaston Jacquet). Presumed dead by his mother, the Countess Mensdorf (Erna Morena), he joined the circus and rose to become “Frattani, King of the Air”. Arriving in Berlin as an adult, Paul re-encounters his childhood sweetheart Madeleine, who earlier left the circus – and now hopes to rejoin. Meanwhile, Mallock has been cheating on his wife and gambling away his fraudulently-earned money. At the Wintergarten, Mallock’s roving eye is caught by Madeleine, whose debut is a triumph. But Madeleine worries about Paul’s dangerous stunts, just as Paul comes to worry that he is endangering their budding romance. (A worry enhanced by the sight of the former “King of the Air”, who is now one-legged and unemployed.) Paul recognizes Mallock and strikes him down when he tries to grope Madeleine. Revealing his true identity, Paul’s reappearance is a joy to his mother but to Mallock a threat to his estate. Threatened by his creditors, Mallock grows desperate and tries to sabotage the trapeze ropes – only to plunge to his death. ENDE.

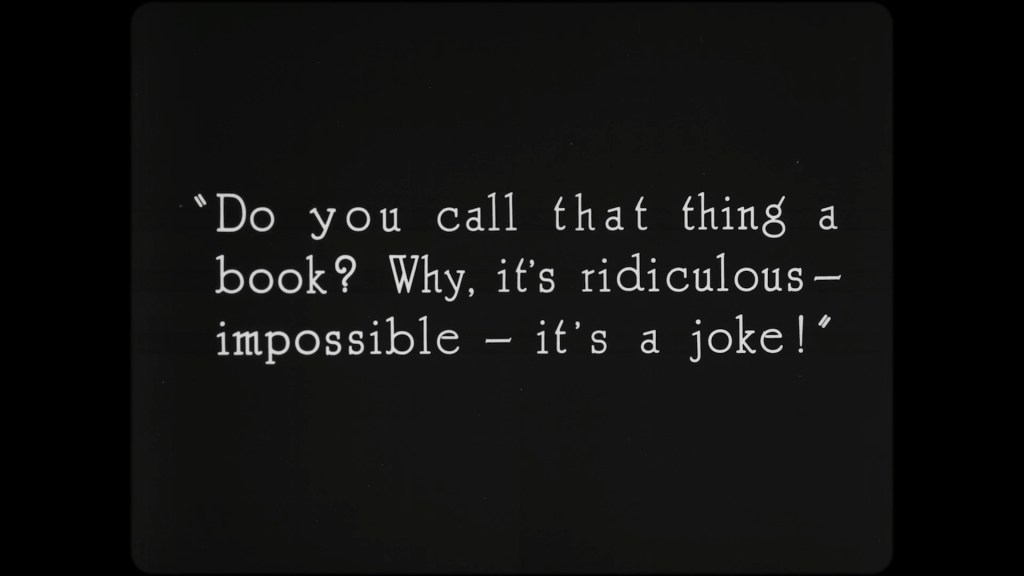

A very enjoyable film, if a tad generic. Its story might be from any variety- or circus-themed film of the silent era, from the earliest features onwards. Danish producers, for example, made a speciality of them in the early 1910s (Den flyvende circus, 1912; Dødsspring til hest fra cirkuskuplen, 1912), remade some of them in the 1920s (Klovnen, 1917 and 1926), and even directed them in Hollywood (The Devil’s Circus, 1926). Romantic rivalry playing out against a backdrop of circus stunts was clearly an appealing setting. And despite the satisfaction of the narrative in Sensation im Wintergarten, the ending is a bit of a dud. The machinations of Wallock amount to very little and his threat goes instantly awry, killing him before anything has happened.

But narrative ingenuity or dramatic depth is probably not the point here. Sensation im Wintergarten is distinguished by its superb staging and camerawork. Even if this could be a story from 1910, its cinematic realization truly belongs to 1929. The film is impeccably lit, impeccably staged, impeccably edited. From the outset, it is filled with fine sequences. The opening flashback to Paul’s childhood, for example, stages his first sight of the circus performers through the windows the school gymnasium. There is a very nice dissolve at the end of the scene to the same space, now deserted and lit only by the streetlamp. It’s evocative and moody, just as when Paul first enters the circus. Here, we see the clown Barry (Wladimir Sokoloff) is introduced in the centre of the rink, pulling an animal from the wings via a lead. The beast that emerges is in fact a tiny dog, who slides reluctantly across the sand. The camera slides before the dog, making the sight both novel and comic. It is a shot of pure delight, allowing us to share the kind of delight that the child Paul feels as he looks on from the wings.

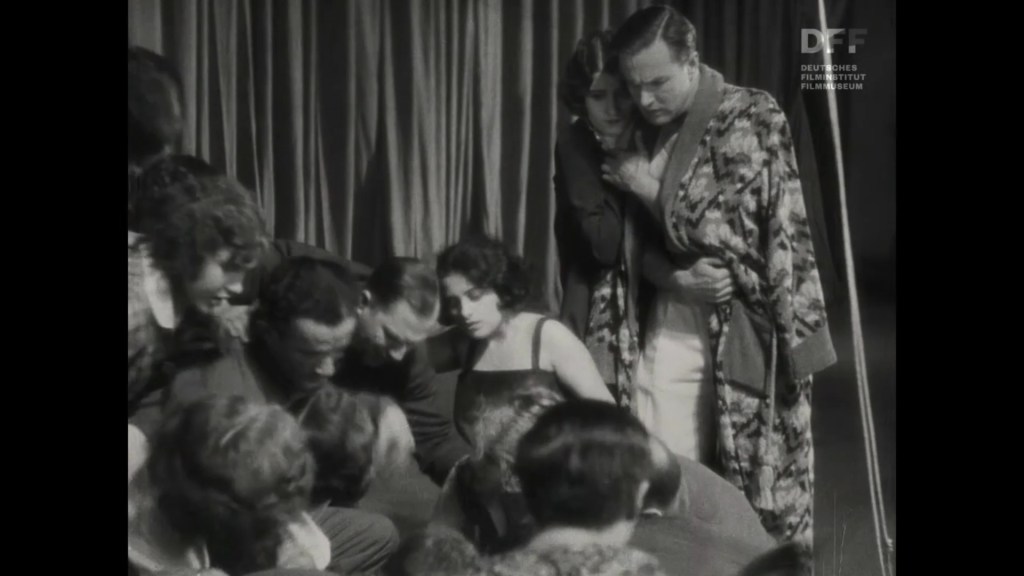

I single out this moment to emphasize that the mobile camerawork is interesting not just in the obvious examples of trapeze-mounted shots for drama, but the less expected ones. Then there are the beautiful travelling shots through 1929 Berlin, the camera gliding marvellously along the streets towards the theatre. But the interior sequences filmed inside the real Wintergarten are simply dazzling. It’s a glorious space, gloriously filmed – you can really feel the size of it, the buzz of the crowd, the drama of the performers on the real stage.

I love the tracking shot in which the side doors of the theatre open and we glide slowly toward the huge space within. It’s like a more realistic version of the shot in Ben-Hur (1925) in which the camera similarly tracks forward into the huge space of the Roman arena. Indeed, in some ways the shot in Sensation im Wintergarten is more enticing. Unlike half real, half matte-painted space of the Circus of Antioch, the Berlin theatre is tangibly real – and the sense of being inside this real space, with its real stage, real seating, real walls, real ceiling, is itself exciting. The unchained camera – swinging from the trapeze, leaping through the air – is a continuation of this sense of a real space being physically explored on screen.

Director Gennaro Righelli takes advantage of this amazing pre-built set by placing his camera everywhere he can: in the audience, behind the audience, in the wings, behind the stage, in front of the stage, in the orchestra pit, behind the orchestra pit, in the corridors, in the dressing rooms… You really get a sense of this location as a complete world in itself, a life that a performer might long for and not want to leave. The real sets are likewise full and rich and complete. There are fine interiors of the Countess’s home, but I was more interested in the smoky restaurants where the show people meet. The sense of a full reality created by the shots that introduce the real streets of Berlin continue into these interior spaces.

For all this, some may feel that it lacks the aesthetic or dramatic punch of Germany’s most famous vaudeville film of the era: Varieté (1925). I dare say I would agree. But this comparison to the most conspicuously well-known film of its genre does Sensation im Wintergarten an injustice. If Gennaro Righelli is not E.A. Dupont (I admit I had never knowingly heard of Righelli), this is no reason to snub his work. Nor should one snub his cast, even though it does not boast anyone as famous as Lya di Putti or Emil Jannings. But Sensation im Wintergarten does feature a reliable ensemble of familiar(ish) names. As Paul, Paul Richter offers no great emotional depth, but he is believable and likeable. (My familiarity with his face is as Fritz Lang’s Siegfried from 1924: another role of presence without depth.) Believable and likeable are also qualities I might say of Claire Rommer as his love interest. They are a charming couple, if one whose inner lives are only sketches rather than detailed portraits. As Mallock, Gaston Jacquet is perfectly suave, perfectly calculating, perfectly callous – a character designed not to possess any depth whatsoever. As Paul’s circus friend, Wladimir Sokoloff is a familiar face from various small roles in this period (including several Pabst productions), and his distinctive features – warm, kind, expressive, comic – make for an engaging sidekick to the lead. If I find I have little else to add to these sketches, it is because the film makes of its characters little more than sketches. They are entirely effective, but nothing more.

Again, I do not mean to talk down this film. Sensation im Wintergarten is a worthy production, and very entertaining. And it’s always good to widen one’s perspective on lesser-known films and directors. As much as I like Varieté, I’d really rather see something new and unknown. Sensation im Wintergarten is most certainly new and unknown. This presentation from Bonn is in fact the world premiere of the new digital restoration, which also provides detailed credits at the start. Per these very useful notes, the original German version of Sensation im Wintergarten remains lost, so this restoration is based on the version released in Sweden. Various missing scenes and shots have been indicated with inserted text, which is much preferable than leaving out important details for the sake of visual continuity. (I wish restorations would do this more often, as it is otherwise impossible to know the differences between original and restored copies.) Despite some missing material, the film looks great – filled with crisp, rich, detailed images. The music here was provided for piano and various other solo instruments by Günter A. Buchwald and Frank Bockius. Catching the rhythms and sounds of the circus, in particular, makes for a very engaging experience. They caught the drama and its tone very well, and I was entertained throughout.

Stummfilmtage Bonn 2025: Summary. As ever, by the time I have finished writing these festival pieces, the festival itself seems long over. And, as ever, I have mixed feelings about my online attendance. I have not engaged at all with online discussion (let alone in-person conversation) about what I have seen, nor have I explored any related festival material other than the brief descriptions of each film on the “details” sidebar for each video. My body and brain have certainly been having to work hard, though in a very different way from those present in Bonn. My early mornings have been a pell-mell flurry of simultaneous viewing and notetaking, followed by late mornings with an equally pell-mell flurry of rewriting and image-capturing. My wrist aches, something odd happened to my lower back, and I feel like I’ve had to cram more quickfire viewing and thinking into this last ten days than I have in many weeks. But ultimately I do enjoy the feeling that I have been forced to live according to the rhythm set by the festival, even if only via online portals with preset time restrictions. While a solitary pleasure, writing gives me a sense of something that will last beyond the ten days – and will hopefully stick in my memory, if not anyone else’s.

It goes without saying that the Stummfilmtage Bonn is an absolutely superb festival. The programme is always filled with some real discoveries, as well as the chance to review some familiar and very worthwhile films. Impeccably presented and prepared for online streaming, I cannot possibly bestow enough praise on everyone involved. (My conversation with the co-curator, Oliver Hanley, last year only led to a greater appreciation of the mad amount of effort involved in putting this on – especially for both live and online audiences.) I hope I will be able to attend in person one year, and indeed to have the kind of lifestyle that would enable me to do so. Until then, I will happily let my life be taken over by the Stummfilmtage Bonn for ten days each year. Long may this opportunity last.

Paul Cuff