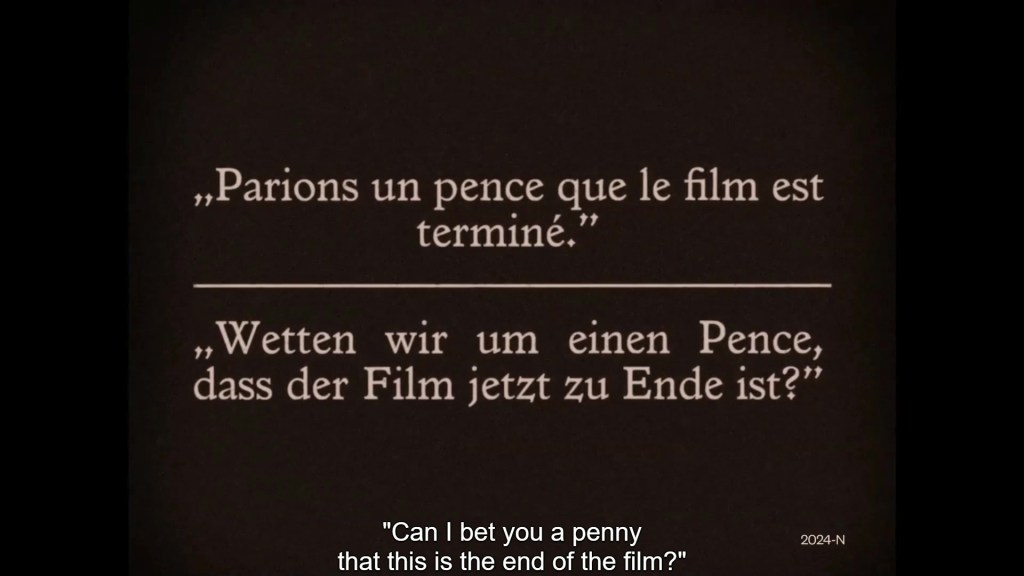

Day 2 of Bonn and already I must take a kind of detour from the programme. Today’s streamed film is Saxophon-Susi (1928; Ger.; Karel Lamač), the same restoration of which I saw via the online Pordenone festival last year. I refer readers interested in the film to that earlier post, while today my comments will primarily address the differences in presentation between the two festivals.

The first thing to note was that Bonn offered two versions of Saxophon-Susi. Aside from the version with musical accompaniment (discussed below), there was a version with Germany an audio-description version for the visually impaired. (Though another audio-description video has text and narrator credits, I couldn’t find any for this specific film.) I was curious to know if this was presented with the soundtrack beneath the descriptive text. It was not, so offers a very curious experience – at least for this non-impaired spectator. I would be very curious to know more about the audience for silent films with audio description. When I attended the online HippFest festival earlier this year, I wrote about the audio-description texts offered there. These were very elaborate, intended for live audiences as much as online spectators, and the texts described the music as well as the action. HippFest also offered brail text for the deaf to accompany screenings, though I cannot comment on the content of these. The Bonn audio description is simpler, offering a straightforward description of the action and a rendition of all the intertitles. Obviously, I am not the intended audience for these alternate presentations – but I would be very curious to know more about (or hear from) anyone who has experienced these presentations as intended.

The second thing to note was the version with musical accompaniment. My comments here require some context… Though this 2023 restoration of Saxophon-Susi has not yet been released on DVD/Blu-ray, it has already accrued at least three new scores. The first was presented in August 2024 at the “Ufa filmnächte” festival in Berlin, where it was accompanied by Frido ter Beek and The Sprockets film orchestra. (Alas, the “Ufa filmnächte” is no longer a streamed festival, so I cannot report on how this score sounded.) For the version streamed from Pordenone in October 2024, there was a piano score by Donald Sosin. As I wrote at the time, this was delightful: catchy, rhythmic, playful, and fun. That said, I regretted the fact that the titular saxophone-playing sequences in the club and on stage had no saxophone on the soundtrack. At Bonn, the musical score offered was for piano and saxophone, and was composed/performed by M-cine (Dorothee Haddenbruch and Katharina Stashik, as they are identified on the video details page). It was great to hear a saxophone as part of the musical accompaniment, since this is a film whose very plot demands this instrument by featured. But the score itself was curiously chaste, which is to say that I found it less overtly fun than Sosin’s piano score from Pordenone.

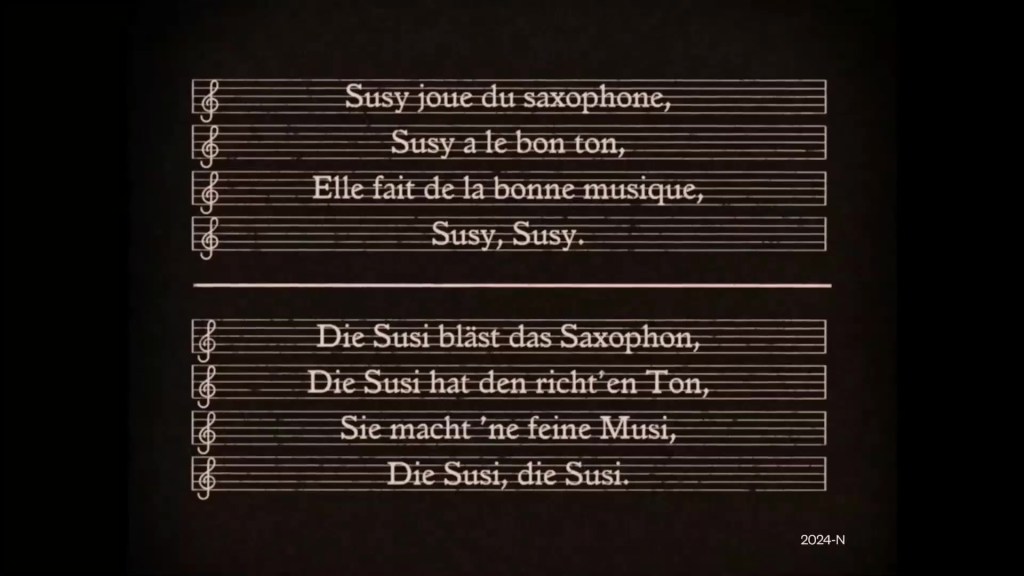

At the premiere in 1928, Saxophon-Susi was accompanied by a jazz orchestra – and the poster for the film’s release in France also includes the promise of a jazz orchestra in the cinema. The film also had a tie-in song, “Die Susi bläst das Saxophon”, composed by Rudolf Nelson. (Both Sosin and M-cine cited this song in their scores, and as I presume did that of Frido ter Deebk in August 2024.) This morning, I dug a little into some contemporary reviews to get more of a sense of the original music. It certainly seems to have been a major part of the value of the live performances. For example, Der Kinematograph (4 November 1928) cites the arranger/conductor Paul Dessau’s “musical wit” and “truly comedic touch” in his score – and live performance at the premiere. The reviewer reports “enthusiastic applause from the laughing, amused audience” at the dance sequences etc. Oh, to see the film with live music and audience…

Lacking an orchestral score in 2025, I spent the rest of this morning listening to the many recordings of “Die Susi bläst das Saxophon” made in 1928 in the wake of the film’s original release. There were various instrumental versions made, such as the peppy version by Efim Schachmeister and his orchestra. The melody was clearly an international hit, as it was exported to the British/US market via The Charleston Serenaders, who recorded a charmingly upbeat rendition outside Germany in 1928. One can also sample a version with lyrics, as sung back in Berlin by Paul O’Montis in the company of the Odeon Tanzorchester. But by far the most pleasing version is the deliciously slow, relaxed instrumental account provided by Marek Weber’s band. I absolutely adore the slow tempo, the way this gives extra space and time for the various soloists to take their turn with the melody. You get the feeling that you’re eavesdropping on a Berlin dance night in 1928. It’s a simply joyous little number in their hands.

Looking up the identities of these various musicians is itself an interesting exercise. The composer of the song, Rudolf Nelson, was a popular cabaret and theatre musician. He was also Jewish, and in 1933 was forced to flee Germany, settling in the Netherlands – where he had to live in hiding during the German occupation. This grim period of history interrupts the biographies of the recording artists of Nelson’s song, too. The Austro-Hungarian Marek Weber was a musician of the old school and purportedly disliked jazz (perhaps this explains his slow tempo in “Die Susie bläst das Saxophon”?), but nevertheless ended up recruiting some of the best jazz musicians in Germany and recording plenty of popular tunes. As a Jew, he saw which way the political tide was turning and left Germany in 1932, ultimately settling in the US. Efim Schachmeister was born in Kiev to Jewish-Romanian parents but made his name in Berlin in the 1920s. He fled the Nazis and eventually ended up in Argentina. Paul O’Montis was Hungarian by birth and made his name on the Berlin cabaret scene. Openly gay, he was forced to leave Germany when the Nazis came to power. Sadly, he was one of many who didn’t flee far enough. After finding refuge in Vienna, after the Anschluss of 1938 he relocated to Prague – but was arrested there in 1939 and, after various relocations, ended up being killed in Sachsenhausen concentration camp in 1940. Such stories are common when researching artists of this period, but somehow the combination of such light-hearted numbers as “Die Susie bläst das Saxophon” in the context of their makers’ lives is especially sobering.

One upshot of this rather divergent morning is my desire to hear a jazz band score for Saxophon-Susi, something in the vein of Marek Weber’s recording of the theme song. If the film gets released on home media, it rather depends on how much effort (i.e. money) someone wants to put into it. What so often happens is that special scores are composed for live show(s), then no money is made available for that score to appear on home media with the film. There are many examples of expensive film restorations released with the cheapest musical option on DVD/Blu-ray. I do hope that Saxophon-Susi gets the score it deserves.

Paul Cuff