La Seine Musicale stands on the Île Seguin, some few minutes’ walk from the last stop on line 14 of the Paris metro. On a warm Thursday afternoon, I find myself among a band of spectators trooping across the bridge towards the concert hall. The hot sun makes us sweat convincingly for the first security check. Tickets scanned, we file through. It is half past five. Several lines lead towards covered checkpoints. Bags are inspected, bodies are searched. We proceed to the doors, where our tickets are scanned once more. Inside, there is a buzz of expectation. I overhear conversations in French, English, German. Further down the lobby, I see a giant projection of the trailer for tonight’s premiere. I catch the words “definitive”, “monumental”, “historic”, “complete”. Above the doors to the auditorium, the same video loops on LCD screens.

The screening is supposed to start at six o’clock, but five minutes beforehand queues still struggle through the three tiers of security outside. Inside, I take a programme booklet and search for my seat. Buying tickets online was not easy. The seating plan was like a nightmarish game of Tetris. With no sense of where each block lay in relation to the screen, in desperation I opted for “gold” tickets. Inside the concert hall, I find with immense relief that my view is superb. Dead centre, two ranks below the projection booth, three ranks above the sound mixing station. (Seemingly, the orchestra is being augmented through speakers to ensure level volume throughout the auditorium.)

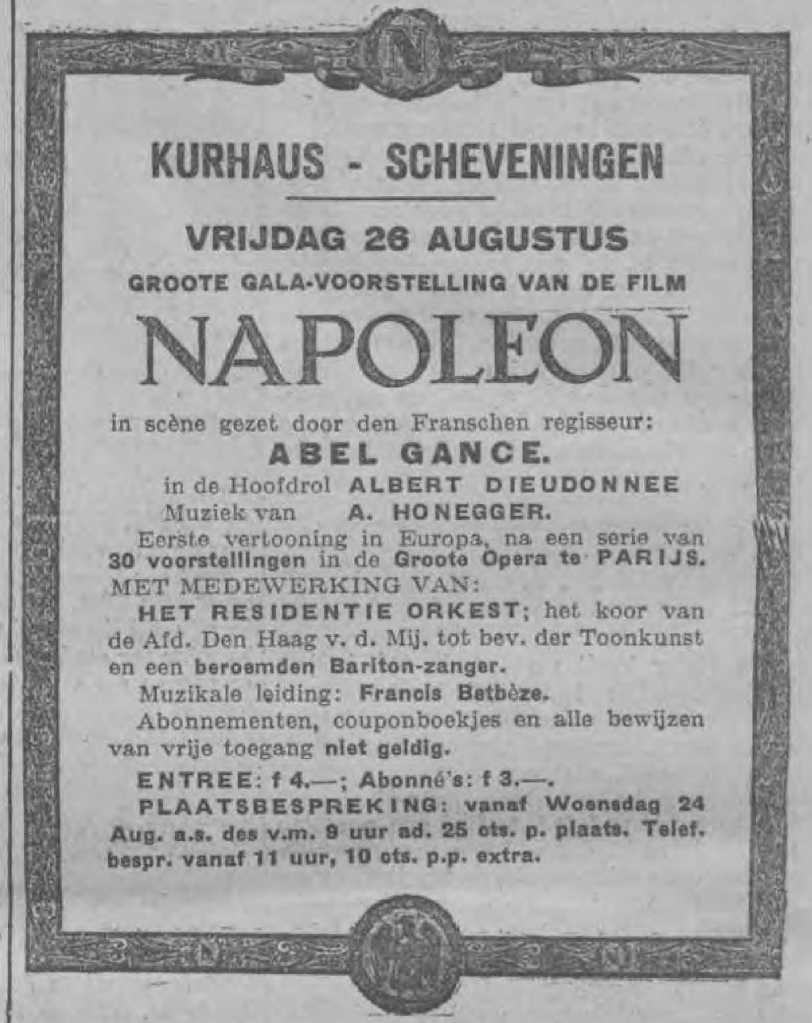

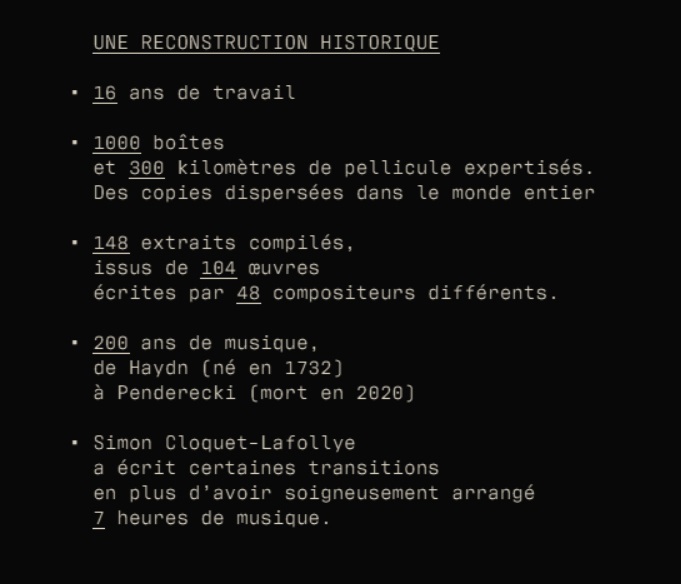

I sit and read the programme. It promises me a kind of accumulative bliss. Sixteen years of work. 1000 boxes of material examined. 300 kilometres of celluloid sorted. A score of 148 cues from 104 works by 48 composers, spanning 200 years of music. (It is as if the sheer number of pieces cited, and the breadth of periods plundered, were proof of artistic worth.) Even the performance space is advertised in terms of gigantism. This is to be a ciné-concert “on a giant screen”. Giant? I look up. The screen is big, but it’s the wrong format. It is 16:9, like a giant television. The sides are not curtained or masked. How will they produce the triptych? The hall fills up. Last-minute arrivals scurry in. I catch a glimpse of Georges Mourier. He has chosen to sit very close to the screen. (Does he know something?) I switch my phone to flight mode and put it away. By the time the lights go down, it must be at least a quarter past six. But what matter a few minutes’ delay compared to sixteen years of preparation? This is Napoléon.

I have indulged in the above preamble because I had been anticipating this premiere for several years. With its much-delayed completion date, the Cinémathèque française restoration of Napoléon seemed always to be on the horizon. Now that it has at last arrived, the marketing generated by its release has swamped the film in superlatives. I have seen Napoléon projected with live orchestra four times before, in London (2004, 2013, 2016) and in Amsterdam (2014), but this Paris premiere outstripped them all in terms of sheer ballyhoo.

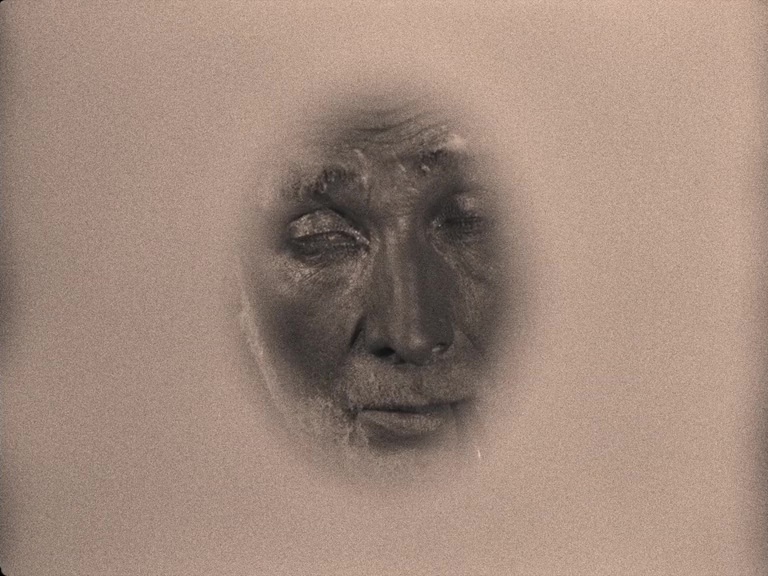

So, what does the new restoration offer? For a start, it looks stunning. The “giant screen” promised me did indeed present the single-screen material in superb quality. Though there was far too much light spill from the orchestra on stage, and no mask/curtains to define the edges of the frame, the image still revealed great depth and detail. Throughout, the photography is captivatingly beautiful. I was struck anew by the sharpness of Gance’s compositions in depth, by the landscapes across winter, spring, and summer, by the brilliance of the close-ups. I fell in love all over again with those numerous shots in which characters stare directly into the camera, making eye contact with us nearly a century later. The young Napoleon’s tears; the smallpox scars on Robespierre’s face; the adult Napoleon’s flashing eyes amid the gleaming slashes of rain in Toulon; the sultry soft-focus of Josephine at the Victims’ Ball. The tinting looked quite strong, but the visual quality was such that – for the most part – the images could take it. (I reserve judgement until I’ve seen the film without such persistent light spill on the screen.) In terms of speed, I was rarely disturbed by the framerate of 18fps throughout the entire film. (As I noted in my earlier post, the 2016 edition released by the BFI uses 18fps for the prologue but 20fps for the rest of the film.) Aside from a few shots that looked palpably too slow (for example, Salicetti and Pozzo di Borgo in their Paris garret), the film looked very fluid and natural in motion. Though some sequences did seem to drag a little for me, this was entirely due to the choice of music (more on this later).

The Cinémathèque française restoration is notable for containing about an hour of material not found in the BFI edition. The longest single section of new material comes at the start of the Toulon sequence, with Violine and Tristan witnessing civil unrest. It provides a welcome fleshing-out of their characters, which were much more present in the longer versions of the film in 1927. (Indeed, in the 1923 scenario that covered all six of Gance’s planned cycle, they were the main characters alongside Napoleon.) Not only are the scenes important for the sake of character, but they also have some superb camerawork: multiple superimpositions of Violine observing the horror, plus handheld (i.e. cuirass-mounted) shots of the scenes in the streets. Elsewhere, there were many new scenes of brief duration – together with numerous small changes across the entire film: new shots, different shots, titles in different places, new titles, cut titles. I welcome it all and greedily ate up every addition. Though most of the contents of this new restoration will be familiar to anyone who has seen the BFI edition, I was continually struck by the fluidity of the montage.

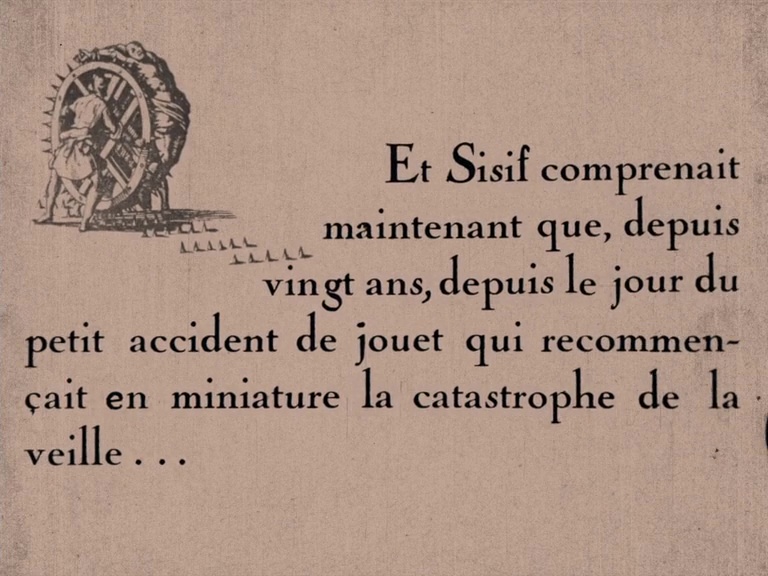

Do these changes fundamentally change or transform our understanding of Napoléon? Not as such. The alterations tend to reinforce, rather than reorient, the material evident in previous restorations. And if the montage is clarified or intensified in many places, there are others when it still feels oddly incomplete. When Napoleon sees Josephine at the Victims’ Ball, for example, the rapid montage of his previous encounters with her includes shots from several scenes that are no longer in the film. Is this a case of Gance not wishing to lose the cadence of his montage, or are there still missing scenes from the new restoration? (There is a similar instance in La Roue, when Sisif’s confession begins with a rapid montage that includes snippets of scenes cut from the 1923 version of the film.)

In another instance, I remain unsure if the additional material in the new restoration helps or hinders the sequence in question. I’m thinking of the end of the Double Tempest, where a new section – almost a kind of epilogue – appears after the concluding titles about Napoleon being “carried to the heights of history”. The additional shots are dominated by Napoleon in close-up, looking around him, a shot that Mourier himself explained (in a 2012 article) originally belonged in the central screen of the triptych version of the sequence. In that version, Gance’s triptych montage used the close-up of Napoleon looking around him to make it seem like he was observing the action on the two side screens. In that context, it made perfect sense. But now, in the latest restoration (which, for unstated reasons, did not attempt to reconstruct the Double Tempest triptych), the shot appears in isolation and looks a little odd. It’s still a compelling image, but it has nothing to interact with on either side, as originally intended. What exacerbates this disconnection between the old and new material is the music that accompanies it. The sequence reaches its climax – in terms of sheer volume, if nothing else – with the slow, loud, dense, chromatic roar of music from Sibelius’s Stormen (1926). (From my seat, I could see the decibel counter reach 89db, the loudest passage of the score thus far.) This cue – an almost unvarying succession of waves and troughs – ends at the point the sequence stops in previous restorations. This is then followed by Mozart’s Maurerische Trauermusik (1785): swift, lucid, succinct, melodic. There was no obvious link between the two musical pieces, which made the new material seem divorced from the rest of the sequence. Even if the film knew what it was doing (and I can find no information to say if this sequence is truly “complete”), the score didn’t.

The music. The role of Simon Cloquet-Lafollye’s score is central to this issue of aesthetic coherence. His musical adaptation is the major difference between the new restoration and previous ones, which featured scores by Carl Davis (1980/2016), Carmine Coppola (1981), and Marius Constant (1992). I will doubtless find myself writing more about this in the future, when I’ve been able to view the new version on DVD/Blu-ray. But based on the live screening, several features strike me as significant.

As (re)stated in the concert programme, Cloquet-Lafollye’s aim was to produce “a homogenous, coherent piece, in perfect harmonic synchronization with the rhythm imposed by the images”, a “score totally new and hitherto unheard that takes its meaning solely from the integrity of the images” (28-29). But these ambitions were only intermittently realized, and sometimes entirely abandoned. Rhythmically, aesthetically, and even culturally, the music was frequently divorced from what was happening on screen. My impression was of blocks of sound floating over the images, occasionally synchronizing, then drifting away – like weather systems interacting with the world beneath it. To me, this seemed symptomatic of the way Cloquet-Lafollye tended to use whole movements of repertory works rather than a more elaborate montage of shorter segments. Using blocks of music in this way also made the transition from one work to the other more obvious, and sometimes clunky. This is most obvious when, for the same sequence, Cloquet-Lafollye follows a piece from the late nineteenth/early twentieth century with something from the late eighteenth/early nineteenth century. It’s not just a question of shifting from more adventurous (even dissonant) tonality to classical textures, but often a difference in density and volume. In part one, Gaubert (the “Vif et léger” from his Concert en fa majeur, 1934) is followed by Mendelssohn (Symphony No. 3, 1842), Sibelius is followed by Mozart (per above); in part two, Mahler (Symphony No. 6, 1906) is followed by Mozart (Ave Verum Corpus, 1791). The music itself was all good, sometimes even great, but in many sections sound and image remained only passingly acquainted. (This is sometimes heightened by the fact that, by my count, thirteen of the 104 works used in Cloquet-Lafollye’s compilation postdate 1927.)

In the film’s prologue, for example, the snowball fight was often well synchronized – though its climax was mistimed (at least in the live performance). But the geography lesson, the scene with the eagle, the start of the pillow fight, and the return of the eagle in the final scene, all failed to find a match in the music. The score reflected neither the precise rhythm of scenes, nor the broader dramatic shape of the prologue. Cloquet-Lafollye ends the prologue with music from Benjamin Godard’s Symphonie gothique (1874). This slow, resigned piece of music accompanies one of the great emotional highpoints of the film: the return of Napoleon’s eagle. In the concert hall, I was astonished that this glorious moment was not treated with any special attention by the score. Why this piece for that scene? Of course, these reservations are no doubt informed by personal taste – and my familiarity with Davis’s score for Napoléon. But there are many examples of significant dramatic moments on screen that cry out for musical acknowledgement, and which Cloquet-Lafollye’s choices ignore. Too often, the score is working in a different register and/or at a different tempo to the film.

All this said, there were sequences where the choices did, ultimately, gel with the image. In the final section of part one, the Battle of Toulon can sometimes drag – and I was wondering if the slower framerate (and extra footage) of the new restoration would exacerbate this. (Certainly, some friends at the screening thought it did.) But here, Cloquet-Lafollye’s movement-based structure did, for me, help structure the often-confusing events of this long section into an effective whole.

In particular, one passage worked both theatrically and cinematically. As the storm and battle reaches a climax on screen, on stage extra brass players began trooping from the wings to join the orchestra. It was a premonition of musical might, realized a few moments later in the form of “Siegfrieds Trauermusik” from Wagner’s Götterdämmerung (1874). I confess I was initially deeply unsure of this choice. (It is, after all, very famous and has its own specific operatic/dramatic context.) As often with Cloquet-Lafollye’s selections, this piece was initially too slow for the images on screen and the vision of hailstones on drums (a clear invitation for a musical response) went without musical comment. Only gradually did the music coalesce with images: the immense crescendo, the switch from minor to major key, and climactic thundering of orchestral timbre, snare drums included, was irresistible. I’d never heard this piece performed live, and it was simply thrilling. (On the decibel reader, Wagner hit 91db – the loudest piece in the entire score. Perhaps the programme notes could have included this in its list of numerical achievements? “More decibels than any previous restoration!”)

But, as elsewhere, Cloquet-Lafollye followed this immensely dense, loud, surging late romantic music with a piece from an earlier era: the “Marcia funebre” from Beethoven’s Symphony No. 3 (1804). As well as not fitting the rhythm of the scenes, this music undercut the gradual shift from mourning to the vision of Napoleon asleep but triumphant. In these final shots, Gance mobilizes several recurrent visual leitmotifs to reaffirm the place of Toulon in the course of Bonaparte’s destiny: the eagle lands on a tree branch nearby, echoing its earlier appearance on the mast of the ship that rescues Bonaparte after the Double Tempest; the morning sun rises above the sleeping general, blazing ever brighter at the top of the frame’s circular masking; the gathered flags are caught in a sudden gust of wind and flutter as brilliantly as Liberty’s superimposed pennants in the Cordeliers sequence or the wind-lashed waves of the Double Tempest; and, in the lower left of the frame, a gun-carriage wheel replicates the last image of the young Bonaparte at Brienne. These images cry out for a musical statement to acknowledge Napoleon’s destiny, but Cloquet-Lafollye just lets the funeral march play out in full – a slow, quiet, trudge to mark the end of the film’s first part. As much as I enjoyed the movement-based structure of the score for Toulon, this didn’t feel the right finale.

These issues of tone and tempo effect comedic scenes as well as dramatic ones. In part two, the Victims’ Ball begins with a title announcing: “The Reaction”. The opening shots – gruff guards, prison bars, bloody handprints – are designed to echo the earlier scenes in the Terror. Convinced of the gravitas of the scene, the audience is unprepared for what happens next: after returning to the establishing shot, the camera slowly pulls backwards to reveal that the “victims” in the foreground are in fact dancing. This carefully prepared joke is lost in Cloquet-Lafollye’s score, which begins the sequence with light, graceful dance music (from the ballet of Mozart’s Idomeneo (1780)). The music gives away the punchline while the film is still establishing the set-up.

Part of me wondered if these elements of disconnection stem from Cloquet-Lafollye’s working method. Per their programme notes, Frédéric Bonnaud and Michel Orier confirm that the score was constructed from tracks taken from existing recordings. Cloquet-Lafollye initially submitted “a montage of recorded music” (17) to the musical team, which suggests he did not begin his work from paper scores or working through passages on the piano. Might this process discourage a more hands-on, score-based construction?

One other point about the score is the inclusion of a single piece from Arthur Honegger’s original music for the film, created for Paris Opéra premiere in April 1927. His name was absent from the musical table of contents issued in the recent Table Ronde publication on Napoléon, so it was a pleasant surprise to see his name in the concert programme. This sole piece, “Les Ombres” for the ghosts of the Convention sequence in part two, was eerie and effective – and distinctive. It is a nice, if brief, acknowledgement of Honegger’s work – though I am puzzled as to why its inclusion was not mentioned until the programmes were issued on the day of the concert. (Cloquet-Lafollye’s essay mentions Honegger only to reiterate that both he and Gance were dissatisfied with the music at the premiere.)

On a similar note, I wonder if Cloquet-Lafollye was familiar with Carl Davis’s score. There are two scenes where the former seems to echo the latter. The first is in Toulon, where Cloquet-Lafollye uses the same traditional melody – “The British Grenadiers” – to contrast with “Malbrough s’en va-t-en guerre” during the build-up to the battle. (In the programme notes, “Malbrough s’en va-t-en guerre” is not credited as “traditional”, but to Beethoven’s Wellingtons Sieg (1813) – though I would need to relisten to the score to discern how closely it follows Beethoven’s version.) The second similarity occurs in one of the few scenes credited as an original piece by Cloquet-Lafollye: “Bureau de Robespierre”. Here, he cites the same popular melodies for the hurdy-gurdy as Davis, and even orchestrates the scene where Robespierre signs death warrants the same way as his predecessor: the hurdy-gurdy accompanied by a low drone-like chord in the orchestra, with strokes of the bell as each warrant is signed. A curious coincidence. (I look forward to being able to listen to these scenes again to compare the scores.)

By far the best section of the music (and the film performance as a whole) was the performance of “La Marseillaise” in part one. I think this was precisely because the sequence forced Cloquet-Lafollye to stick to the rhythm of events on screen, moment by moment, beat by beat. There was also the tremendous theatricality of seeing the choir silently troop onto stage in the concert hall, switch on small lamps above their sheet music, and wait for their cue. The tenor Julien Dran launched into the opening lines, synchronizing his performance with that of Roget de Lisle (Harry Krimer) on screen. When the choir joins in, their first attempt is delightfully disjointed and out of tune. This makes their final, united rendition all the more satisfying and moving. Here, too, the montage of the new restoration evidences the stunning precision with which Gance visualizes “La Marseillaise” on screen: each line and word of the anthem is carried across multiple close-ups of different faces in a tour-de-force of rapid editing. The long-dead faces on screen were suddenly alive – the emotion on their faces and the song on their lips revivified in the theatre. I had never heard “La Marseillaise” performed live, and in the concert hall I wept throughout this rendition. (Even recalling it – writing about it – is oddly powerful.) It was one of the most moving experiences I have had in the cinema. But seeing how well this sequence worked – images and music in perfect harmony – makes me regret even more the way other sections were managed. Considering that Cloquet-Lafollye’s score draws on 200 years of western classical music for its material, and that it has had several years to be assembled, I was disheartened to find so many scenes which lacked a sustained rhythmic, tonal, and cultural synchronicity with the film.

Polyvision. All of which brings me to the film’s finale. I wrote earlier that the screen size (and lack of masking) made me wonder how the triptych would be handled in the Paris concert hall. Since there was no rearrangement of the screen or space for the second evening’s projection, I was even more puzzled. How would they fit the three images on screen?

Eventually, I got my answer. When Napoleon reaches the Army of Italy and confronts his generals, something peculiar started happening to the image: it started shrinking. This was not a sudden change of size. Rather, like a form of water torture, the image slowly, slowly, got smaller and smaller on the screen. To those who had never seen Napoléon before, I cannot image what they thought was happening; did they belief that this gradual diminishment was Gance’s intention? As the image continued to shrink, someone in the audience started shouting. I couldn’t make out what he said, but something along the lines of “Projectionist!” Was he shouting because he didn’t know what was happening, or because he knew what should be happening? I would have started shouting myself, but I was struck dumb with disappointment. More than anything, it was the agonizing slowness of the image wasting away that made me want to sink into the ground rather than face what I realized was coming.

When the image had shrunk enough (making me feel like I was fifty rows further back in the auditorium), the two additional images of Gance’s triptych joined the first. This was the first time I’ve seen Napoléon projected live when the audience didn’t spontaneously applaud this moment. Why would they applaud here, when the revelation was rendered so anticlimactic? Those who hadn’t seen the film before must have been baffled; those who had seen the film before were seething. If the organizers had announced in advance that this was going to happen, it would still have been bad but at least those who had never seen the film would know it wasn’t the way Gance wanted it to be seen. As it was, nothing was said – and the consequences of this decision unfolded like a slow-motion disaster. I’m not sure I’ve ever been so disappointed in my life. Every time I’ve seen the triptych projected as intended, I’ve been almost physically overwhelmed by the power of it. (In Amsterdam in 2014, before a triptych forty metres wide and ten metres high, I thought my heart was about to burst, so violently was it beating.) This time, I was taken utterly out of the film. I could hardly bear being in the concert hall.

All this was exacerbated by the choice of music. Gance’s vision of the assembly of Napoleon’s army, the beating of drums, the shouts of command, the immense gathering of military and moral force, and the revelation of the triptych, is one of the great crescendos in cinema – and the transition from single to triple screen is a sudden and sensational revelation. But Cloquet-Lafollye accompanies these scenes with “Nimrod” from Elgar’s Enigma Variations (1899): slow, restrained, stately music that takes several minutes to swell to its climax. Rhythmically, it is virtually the antithesis of the action on screen. Culturally, too, I thought it was utterly absurd to see Napoleon reviewing the French army to the music of his enemies – the very enemies we saw him fighting in part one. Furthermore, “Nimrod” isn’t just any piece of British orchestral music, but almost a cliché of Englishness – and of a certain period of Englishness, a century away from the scenes on screen. This was followed by the opening of Mahler’s Symphony No. 6, which was at least swifter – but only rarely synchronized in any meaningful or effective way with the images of Napoleon’s invasion of Italy. (Chorus and hurdy-gurdy aside, Cloquet-Lafollye’s score does not respond to musicmaking – bells, drums, bugles – within the film; in the finale, the drumroll of the morning reveille on screen goes unechoed in his orchestra on stage.)

In the final few minutes, Napoleon’s “destruction and creation of worlds” bursts across three simultaneous screens: lateral and consecutive montage combine; shot scales collide; spatial and temporal context are intermingled. Finally, the screens are tinted blue, white, and red – just as Gance simultaneously rewinds, fast-forwards, and suspends time. After this incalculable horde of images flies across their breadth, each of the three screens bears an identical close-up of rushing water. This is an image we first saw during the Double Tempest when Bonaparte sets out to confront his destiny – there, the water churns in the path of his vessel, borne by a sail fashioned from a huge tricolour; now, the screen itself has become a flag: the fluttering surge of the ocean is the spirit of the Revolution and of the cinema. The triptych holds this form just long enough for the spectator to lose any sense of the world beyond it, then vanishes with heart-wrenching suddenness. The elation of flight is followed by the sensation of falling to earth.

But what music does Cloquet-Lafollye chose for this visual apocalypse, this lightning-fast surge of images? During the last passage of the Mahler, I saw the choir troop back onto the stage to join the orchestra. Was this to be another performance of “La Marseillaise”? No. As the Army of Italy marches into history, the choir and orchestra on stage began their rendition of Mozart’s Ave Verum Corpus – music of the utmost slowness and serenity, of absolute calm and peace. It is perhaps the most ill-conceived choice of music I have ever seen in a silent film score. I’ve sat through far, far worse scores, but none has ever disappointed me as much as this single choice of music. When the choir started singing, I honestly thought it must be a mistake, a joke – even that I was dreaming, the kind of absurd anxiety dream where something impossibly awful is happening and there is nothing you can do to stop it. While Gance was busy reinventing time and space, hurling cinema into the future, my ears were being bathed in shapeless placidity. Instead of being bound up in the rush of images, I was sat in my seat as my heart sank through the floor.

How was I meant to feel? What intention lay behind this choice of music? Why this sea of calm tranquillity, this gentle hymn to God, this sense of exquisite grace and harmony? On screen, Gance explicitly compares Napoleon to Satan in the film’s final minutes – the “tempter” who offers the “promised land” to his followers; and our knowledge that this hero is already doomed to corruption and to failure is suspended in the rush of promise that history might, could, should have been different, that the fire of the Revolution might yet inspire other, better goals. Yet from the Paris stage on Friday night, Mozart’s hymn to God carried serenely, blissfully, indifferently over the fissuring, rupturing, exploding imagery on screen – beyond the last plunge into darkness, beyond Gance’s signature on screen, until – having reached the end of its own, utterly independent itinerary – it faded gently into silence. I did not understand. I still do not understand. I sat in bewilderment then as I write in bewilderment now. In combination with the shrunken triptych, this musical finale seemed like the ineptest imaginable rendering of Gance’s aesthetic intentions. (In the lobby afterwards, an acquaintance who was very familiar with the film put it more bluntly: “What a fucking disgrace.”) Roll credits.

Summary. But how to summarize this Parisian ciné-concert of Napoléon? I am still digesting the experience. I wouldn’t have missed this premiere for the world, but aspects of the presentation deeply upset me. Part of my disappointment is doubtless due to the intensity of the marketing around the release of the Cinémathèque française restoration. In my review of the Table Ronde publication that coincides with this release, I expressed reservations about the language with which the restoration has been described, as well as the misleading equivalencies made with previous versions of the film. The same aspects are repeated in the programme notes for the screening, which reproduces the essays by Costa Gavras, Georges Mourier, and Simon Cloquet-Lafollye. The new pieces by Frédéric Bonnaud and Michel Orier (“Comme une symphonie de lumières”) and Thierry Jousse (“Abel Gance et la musique”) are in much the same vein.

In the programme, only the last line of credits cites a precise length for the version we are supposedly watching: “Grande Version (négatif Apollo) / 11,582m”. This length is a metric equivalent of the 38,000ft positive print that Kevin Brownlow (in 1983) records Gance sent to MGM in late 1927. (As opposed to the 9600m negative print that Mourier, in 2012, cites as being assembled for international export at the same time in 1927.) The total amount of footage in the MGM positive included the material used for all three screens of both the Double Tempest and Entry into Italy triptychs, plus (Brownlow assumes) alterative single screen material for these same sequences. The total projected length of the print is given as 29,000ft (a length of such neatness that it suggests approximation). At 18fps, this 29,000ft (8839m) would indeed equate to the 425 minutes of the Cinémathèque française restoration. But are its contents (or two-part structure) the same? There is still no information on how Mourier et al. distinguished the contents of the “Grande Version” from that of the (longer) Apollo version. (Or, indeed, how to distinguish the contents of the “Grande Version” from the contemporaneous 9600m version.) Without more clarification, I’m unsure if the figure of 11,582m in the programme notes truly represents what we are watching. Any differences between the 1927 and 2024 iterations of the “Grande Version” would not matter were it not for the fact that every single press piece and publication relating to the film insists that the two are one and the same thing. Finding even the most basic information about runtimes and framerates is hard enough amid the perorations of marketing.

None of this should obscure the fact that this restoration really does look very good indeed – absolutely beautiful, in fact. And I must reaffirm that Cloquet-Lafollye’s score is not all bad, and sometimes effective – but I simply cannot understand the finale. Even if the image hadn’t shrunk in size in the concert hall, the music would have baffled me. In combination with the botched triptych, it was simply crushing. I still struggle to comprehend how it can have been allowed to take place at the premiere of such a major (not to mention expensive) restoration. Some of the friends with me in Paris had at least seen Napoléon in London or Amsterdam, so knew what it should look (and, ideally, sound) like. But I felt devastated for those experiencing the film for the first time. Only a proper projection of the triptych, as Gance intended, on three screens, will do. I can scarcely believe that the organizers booked a venue in which the outstanding feature of their new restoration could not be adequately presented. I am sure that arranging the forces involved in this concert was both hideously expensive and exhaustingly complex. But why would you go to all that trouble when the film can’t be shown properly? I remain dumbfounded.

One aspect of the Paris concert that I cannot criticize is the musical performance. Throughout both nights, the musicians on stage provided a remarkably sustained, even heroic accompaniment. Frank Strobel conducted the Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France for part one (Thursday) and the Orchestre National de France for part two (Friday), together with the Chœur de Radio France (both nights), with immense skill. I have admired his work for silent films over many years, including the premiere of La Roue in Berlin in 2019, and I can hardly imagine a better live performance being given of this score. The audience offered regular applause throughout the film, which was richly deserved. Indeed, there was a great deal of communal enjoyment throughout the concert that I found infectious. (This was evident even beyond the musical performance. There is no music during any of the opening credits, so the Paris audience amused itself by applauding each successive screen of text. This got increasingly ironic, and there were even some laughs when the “special thanks to Netflix” credit appeared.)

If I left the concert hall on Friday night with a heavy heart, it was because of an overwhelming sense of a missed opportunity. This was a long-awaited and much-heralded premiere, and I had so wanted it to be perfect. The restoration is a ravishing visual achievement, offering (thus far) the most convincing montage of this monstrously complex film. But I remain unconvinced by the new score. Given its stated remit of precise synchronization, too much of it washes over the images – and sometimes directly contradicts the film’s tone and tempo. Its soundworld is neither that of the film’s period setting, nor that of the film’s production. In either direction, something more appropriate could surely have been achieved. Bernd Thewes’s rendition of the Paul Fosse/Arthur Honegger score for La Roue is a wonderful model of musical reconstruction, offering a soundworld that is both historically informed, aesthetically coherent, and emotionally engaging. Alternatively, Carl Davis’s score for Napoléon is a model of musical imagination: respecting both historical and cinematic dimensions, it is sensitive, intelligent, witty, and in perfect synch with the film’s every mood and move. I cannot say the same of Cloquet-Lafollye’s work. So while I offer my utmost and enthusiastic praise for the work that went into the Cinémathèque française restoration, I resist the idea that this presentation of Napoléon is “definitive”.

Paul Cuff