The Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition left Plymouth on 8 August 1914, a few days before Great Britain declared war on Germany. Leading the expedition was Sir Ernest Shackleton, whose goal was to make the first land crossing of the Antarctic continent. His ship, the Endurance, held 28 men, 69 dogs, and a cat. One of those men was the Australian photographer, Frank Hurley. As the ship sailed south, first to Buenos Aires, then to South Georgia, and finally into the Weddell Sea, Hurley filmed a record of the voyage. By the end of 1914, the Endurance was in the midst of thickening fields of ice and a long way short of its destination. Soon the ship was imprisoned and adrift in the frozen water—and Frank Hurley clung on to his film even as the expedition looked as though it might be doomed…

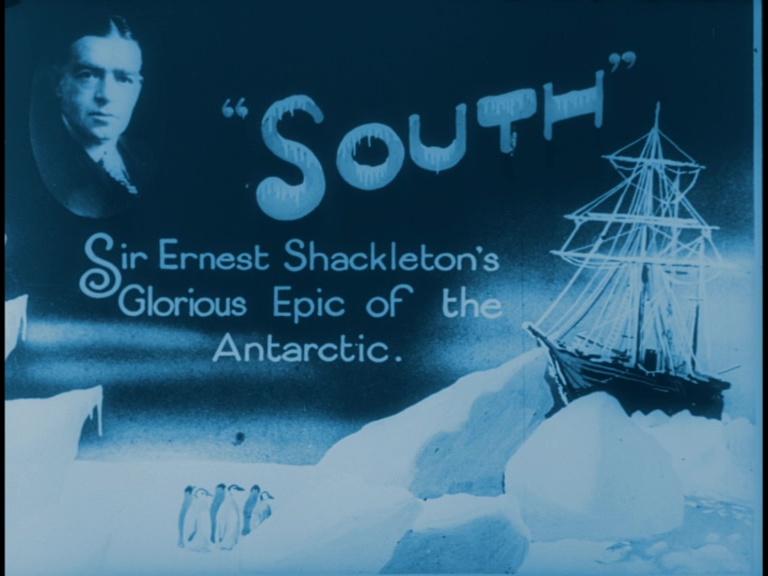

South: Sir Ernest Shackleton’s Glorious Epic of the Antarctic (1919; UK; Frank Hurley)

The opening title is a painted design, complete with portrait of Shackleton, the Endurance, and a small group of penguins. It thus unites the film’s subjects: a record of one man’s most famous exploit, the record of a ship’s fate, and a glimpse of Antarctic nature. The opening text says the film presents “a wonderful and true story of British pluck, self-sacrifice and indomitable courage”. (The text made somehow safer, softer, by the painted icicles, by the painted penguins standing like a kind of audience at the bottom of the frame.)

Portraits of the leaders: Shackleton, Captain F. Worsley, Lieutenant J. Stenhouse, Captain L. Hussey. The men are smiling, laughing; Hussey his playing his banjo. It’s informal, matey, but the men are in military uniform, linking their bravery with the wider bravery of the war. Now the men are shown in Antarctic dress, against the painted snows of a studio; they smile, aware of the comic falseness of this show they’re putting on for the camera.

But here is reality: the Endurance setting off from Buenos Aires. (See that stern? You can recognize it from the photographs taken in 2022, 3,000m below the surface—where now resides the bodily ghost of this living image.) The world as it was, in late 1914.

On board, the camera captures the awkward limits of the deck and the dozens of dogs whose kennels line the sides. The watery horizon bobs in the background. The dogs are being fed. The dogs are being groomed. Puppies born are sea are introduced to the pack. The dogs are seasick. (Suddenly, that madly bobbing horizon attains more significance.) A dog called “Smiler”. The title asks us to “watch carefully” to see him smile. (It’s a mad grimace, not a smile.) But I like being addressed in this way, enjoined to notice something that the crew noticed 112 years ago—and being able to see it on screen, and to be curious and amused as the crew were curious and amused 112 years ago.

Here is Hercules, “the strongest dog in the pack”. We are asked to watch his condensed breath to see how cold it was: to get a sense of the feel of the air, the density of the cold. And here is that breath, longed since exhaled, still blooming white on film. Odd, and oddly moving, to watch the rate of a dog’s breath, the motion of his living body—all this time later.

Shackleton takes a reading from the sun, his eyes almost glancing into camera as he looks up from the binnacle. The film has many of these curious awkwardnesses: of the crew members going about their business, but suddenly becoming aware that they are now performers, performing for the camera, for audiences, for the future, for all eternity.

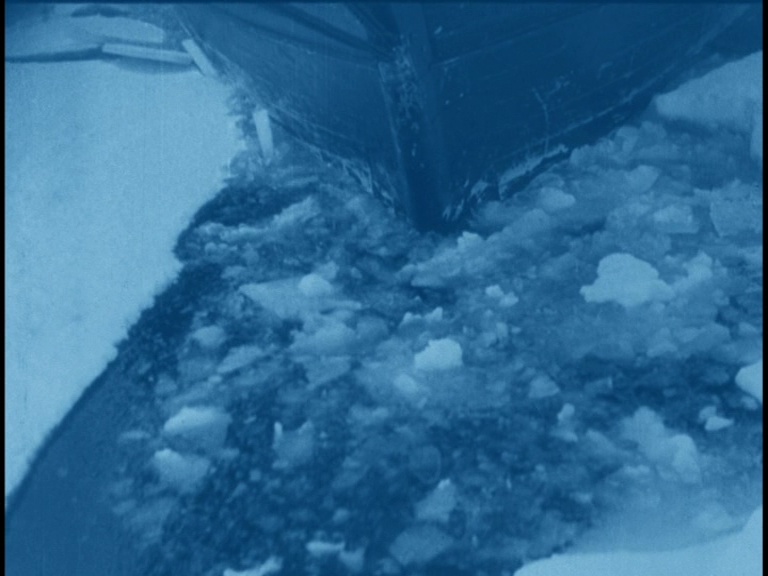

Icebergs glow green. The sea is pale grass. But just as the landscape feels distant, apart, somehow lacking or ungraspable in its paleness—the ice often a kind of visual absence on screen—Hurley captures the most extraordinary series of shots in the film. He must have climbed the mast, have clung on with his legs as he held and cranked the camera with his hands. Thus, he looked down to the foremost part of the Endurance. We see another man, a blue silhouette, legs akimbo, straddling a tiny platform suspended from the bowsprit. And below him, the ice-covered sea. Hurley knows he’s got the perfect shot: look at the way the shadow of the bowsprit is at the bottom left of frame. The shadow serves to show the nature of the ice below it, to emphasize the hoped-for momentum of the ship. It’s also a kind of image being produced by the ship: the ship and its shadow is a neat metaphor for the very film we are watching. Look how the top corners of the frame are rounded by the aperture: the close border intensifies our concentration on the front of the ship. What follows is a sequence of spliced-together shots wherein the whole drama of the voyage is contained in a single image. Can the ship keep going? How long will the ice break and make way for the vessel? The man on the bowsprit looks over his shoulder. You realize he’s sat facing the ship, to observe the hull’s stability in breaking the ice. Under him, the blank ice splits to reveal the deep blue of the sea. The marvels of toning, here: the colour dye clings to the black tones of the image, leaving the highlights untouched. So the sea is deepest blue, and the gradations of the ice—from bright white to tainted blue—are shown in the range of tone. It renders the drama of ice tangible in colour: you can feel how thin is the ice, but also get a sense of how cold is the sea.

This short sequence—occupying barely a minute on screen—is doubly arresting for the sense of time it captures. Hurley splices four shots together, letting each run directly into the next. As the breaks in the ice draw attention to the space being traversed, so these filmic cuts are fissures in time. Slabs of history appear in each shot or are erased in the gaps between.

Next, we see the bow ramming its way through the ice. It’s not as dramatic as the previous shots, but then you realize that Hurley must have suspended himself from the same place on the bowsprit we have just seen filmed from the mast—and suddenly the very act of filming provides the drama. There are eleven shots in this sequence: it must have proved a more illustrative set-up for Hurley to demonstrate the mechanics of the ships progress.

When Hurley cuts back to the view from the mast, the sequence as a whole attains even greater weight: for now when the ice splits before the bowsprit, the film carries with it the impetus from the last shots. The audience is given more of a sense of the stubbornness of the Endurance, the way it bludgeons its way forward. There follow more shots from the mast, each following directly from the last. At one point, you see the shadow of the mast from which the scene is filmed swing across the bottom of the frame: the ship is changing direction, the sun passing over its shoulder. And as it does so, a split in the ice flashes darkly through the ice. (I think I could watch these miraculous shots forever, they’re so hypnotic.)

Hurley casts his eye over the side: a view of seals mobbing their way through the water. And now huge icebergs; they are as wide as whole regions, as high as mountains; the water on the sea, combined with the orange tinting, gives them real mass on screen. Now the image is blue-tone-pink, a combination I always love to see—though here the effect is lessened by the fact that Hurley uses it to colour a still, rather than moving images. Already the film is running out of film to record its adventures. It’s a kind of visual arrestment that augers the spatial arrest of the Endurance. The film continues until it becomes stuck fast.

Indeed, the very next shot is of the icebound ship, borne aloft on frozen waves. Closer views show the crew at work, pickaxing the ice in a vain attempt to make a channel for the Endurance to escape. Huge saws appear, each pulled and pushed by half a dozen men. Then the ship pulls back, gaining space to charge. We see Shackleton on the bow, looking anxiously down into the waters. The ship’s “charge” looks pitifully slow: we’ve seen the men at work, and know what effort it has taken to break up even this much ice. The Endurance swings toward the camera, whose presence suggests a kind of full stop, a point where the ship surely can’t pass. And it doesn’t. Instead of filming the inevitable halt, Hurley cuts to a title: “All progress at an end”. In the next image, the stillness is captured by a still: the expedition really has come to a halt.

We see the ship in stasis, the crew too—lined up for a photo. (Hurley is the only absentee, the title tells us: again, a reminder of the somehow independent, detached existence of the camera.)

A new life, of obdurate isolation. Water must be taken from the frozen snows and brought on board. We see the endless manual labour of keeping life going. Life keeps going onboard, too: here are a new batch of puppies, which will spend their whole lives in and around this same space.

Animals also come in the form of our first glimpse of live penguins: a surreal group of onlookers to the marooned crew. But it is to the dogs that Hurley keeps on returning: we see them being taken to work on the sleds, and it is the dogs who enable the film’s only land-based tracking shots. The camera is perched on a sled, watching the teams race along the ice. Now the dogs are playing with the crew, being manhandled for the camera to show off their size and thickness of hair.

What kind of film is Hurley now making? The expedition has come to a halt. We see the ship stuck by day, and by night we see a still (taken “with eighteen flash lights”) of the ship’s ghostly form in the blue-black intensity of permanent night. What else can Hurley film? We see a primitive tractor at work, but it looks more like play: the vehicle is puny beside the Endurance, punier still in midst of the frozen wasteland. So Hurley shows us dredging for underwater life (which a title reassures us is of great scientific importance), and a man sifting the catch. Creatures too small to show on film are imprisoned in jars that will never reach a laboratory.

The ship is being lifted out of the sea by the mounting ice. The process is too slow to film, so Hurley shows us the aftereffects: the ship being tilted, twisted, jostled. All hope is lost, a title relates (how much time passes between shots, here?) and the dogs are among the contents of the ship being slid via canvas sheets onto the ice for safety. More shots, the time between which marks the slow death of the Endurance: we see successive views of the ship, lower and lower in the frozen water, her masts snapping and tumbling, then sawn for wood by the crew.

The film, too, breaks down. Not only are we given still photographs instead of moving images, but we are given paintings instead of stills. The most miraculous part of the expedition goes entirely unfilmed: the crews’ slog across the ice, the setting sail on small boats, the landing on Elephant Island, the parting of the crew into two groups, Shackleton’s journey over 1,300 kilometres to South Georgia to get help, and the return to Elephant Island to rescue the last group of the crew.

We are also denied the story of how Hurley’s film came to survive at all: how Hurley himself broke Shackleton’s orders; how he stripped off and dived into the icy waters swamping the Endurance to rescue sealed containers of filmstock and glass slides. He risked his life to get the film off the sinking ship, and again by jettisoning food to make way for his negatives on the sleds and boats in which they made their perilous journey to safety.

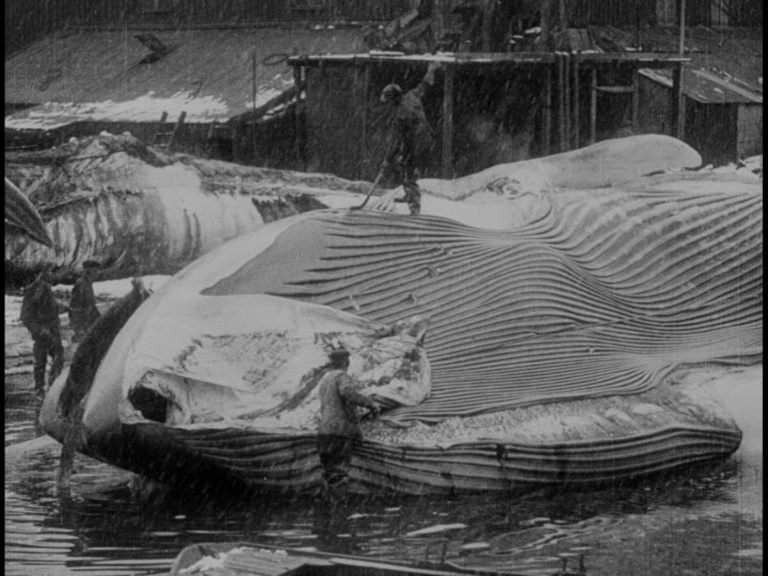

Instead of all this, the film offers a retrospective return to the locations of the unfilmed drama: to the starkly beautiful parts of South Georgia where Shackleton and his five companions came and crossed to reach help. And we see Stromness Whaling Station, as bleak a place as you can imagine: dark wooden huts, trails of smoke, and the steaming carcasses of whales lying in the harbour. We see the stripping of blubber, which is as gruesome as it sounds. It was here that Shackleton first made contact with the outside word. What a strange paradise this dreadful place must have seemed to those men.

As if in answer to the grim sight of hacked-up whales, Hurley returns to living nature: to frolicking seals, to birds of all kinds. Despite the film’s narrative having diverged entirely, Hurley clearly enjoyed some of the shots he took. He finishes one sequence on seals with a long close-up of one scratching its chin and belly, to which Hurley appends the title “End of a perfect day.” There follow many views of penguins: penguins running, penguins staring at the camera, penguins mothering, penguins swimming.

It’s a shock when the film returns to its narrative of Shackleton: for we suddenly get views of the triumphant entry of the crew of the Endurance into Valparaiso aboard a Chilean tug, in May 1916. So much time has passed since we last saw contemporary footage of the crew that it’s hard to reconcile ourselves to the tone of the ending: “Thus ends the story of the Shackleton Expedition to the Antarctic—a story of British heroism, valour and self-sacrifice in the name and cause of a country’s honour. The doings of these men will be written in history as a glorious epic of the great ice-fields of the South, and will be remembered as long as our Empire exists.” So say the last titles, followed by a view of a sunset at sea. THE END.

South is a flawed film, narratively speaking, since it cannot represent the most famous part of the expedition’s story in any but the most inadequate terms: paintings, stills, and summary titles. Of course, the footage was exhibited in a variety of ways in the silent era—including illustrated lectures, complete with narration. We’re also left with more questions that the film (as it stands) cannot, or dare not, answer. What happened to all the dogs once the crews decided to sail for land? (They were all shot, of course.) What happened to the crew when they returned to war-torn Europe in 1916-17? (Hurley himself became a war photographer of great renown; but the others?) What was the effect of the years-long isolation on the crew of the Endurance? (The film cannot scratch the surface of these men’s inner lives.) Later, fictional, films would try to investigate these ideas. But the mere existence of South is a kind of triumph, given that Hurley had been ordered to abandon all his images with the wreck of the Endurance. It is also a triumph of images: the views of the outward voyage and entrapment are spellbinding, and offer an amazing glimpse of what many of the men on screen might have believed was a doomed expedition.

It’s worth noting that among the many extras on the BFI release of the film are nineteen minutes of “unused” footage taken by Hurley. But clearly the footage was used, as it comes complete with the same painted title designs seen in the film itself. (Though the booklet notes say the footage is “tinted and toned”, in fact it is monochrome.) In her liner notes, Bryony Dixon says that “the negatives [of South] were reused multiple times to tell the story in different ways”, including a 1933 sound film, Endurance. So which version does the additional footage come from? The booklet tells us not. It’s a shame the footage was excluded from the 1919 version of the film, as there are some curious scenes. We see more studio footage of Shackleton and co., acting awkwardly for the camera against painted icebergs. Then there is a game of football held on the ice, haunted by the imprisoned silhouette of Endurance in the background. There is closer footage of the crowds in Valparaiso (was it deemed less heroic to see the curious faces in the crowd, staring at the camera?). Then there is a more extended final scene of the sunset at sea. I wondered if the idea of a sunset was Hurley’s dig at the idea of “as long as our Empire exists”. In the alternate version, the sense of humour is underlined: for the sunset is seen through a porthole, the glass of which is then shut, followed by the shutter itself. It’s a kind of double eclipse, and a wittier way—visually, if not thematically—to end the film than is apparent in the 1919 version.

But I mustn’t complain, for the BFI’s presentation of the film is superb: the footage looks beautiful, and Neil Brand’s score (for chamber orchestra) is excellent. Such documentary films can be a very difficult project to score, but Brand keeps up with the images, and makes a coherent whole of the film’s disparate material. My final word must go to Frank Hurley, whose strange, beautiful images still captivate. They, at least, have outlived the Empire.

Paul Cuff