As promised last time, I have been watching more recreations of Great War battles produced by British Instructional Films. Unlike The Battles of Coronel and Falkland Islands, these films focus on the land battles of the Western Front. Like Walter Summers’s naval production of 1927, they offer “reconstructions” of real events using as much military personnel and equipment as possible. The exact genre of the productions is difficult to state. The BFI liner notes for their DVD/Blu-ray edition of The Battles of Coronel and Falkland Islands calls them “docudramas”, while the DVD edition of Ypres (discussed below) refers to them as “documentaries”. I’m sure a worthwhile but ultimately tedious (or tedious but ultimately worthwhile) debate exists in critical literature about what exact term refers to what exact kind of film. Shall I employ “docudrama” here? I’m not sure. I think simply “film” is best, since they appeared in cinemas per any other form of feature-length presentation, and I’m interested primarily in what kind of experience they offer rather than what label to pin to them.

Two of these films I have watched via the BFI Player. The third, Ypres, I watched via a DVD edition released by Strike Force Entertainment (now there’s a name). This is the only film that has received a physical media release. Since I’m a sucker for physical media, and did not wish to pay the BFI £3.50 to “rent” a video file, I cheerfully spent £3.48 for the DVD on eBay. As much as I wish to support the BFI, I’m also an immensely stubborn and immensely cheap human being. Thus, I price-watched the DVD for nearly a month until it fell below the BFI rental price. All to save two pence, and to make sure I had a copy of the film to keep for as long as I wish. That said, I am still relying on the few sentences of the video description available (without paying £3.50) via the BFI Player to contextualize the films. Thus, I learn that the BIF films of the 1920s were “released annually around Remembrance Day” (11 November) and were hugely popular records of wartime events. So, what kind of films are they? And how comparable are they to the one BIF film that the BFI has given a physical media release?

Ypres (1925; UK; Walter Summers). I suppose I must begin with a few facts, for anyone not familiar with this particularly resonant piece of British history. Ypres is a town in Belgium that the British army and its allies defended for almost the entirety of the war. There were three major battles (in 1914, 1915, and 1917), the first being a German effort to capture Ypres and the second and third being Allied attempts to throw the Germans back. The Allied frontline bulged around the town in what became known as the “Ypres salient”, and the Germans occupied the scant higher ground to the east, from which they could observe and bombard the British lines and the town itself. Ypres was reduced to rubble, and the salient around it to a nightmarish wasteland of rotting flesh and filth. The first battle cost around 220,000 casualties, the second 100,000, the third somewhere over 500,000. Between late 1914 and late 1917 the frontline, it need hardly be added, moved barely more than four miles. Since the British and Commonwealth armies spent most of the war occupying and fighting for the salient, the name “Ypres” has a particular resonance in their collective culture. This is also my culture. Certainly, I have been fascinated by the war and by the horrors of this place in particular since I was a child.

The figures I have cited above are not mentioned in Summers’s film of 1925. Made to commemorate the tenth anniversary of (at least) the first two battles, it announces its emotional (and cultural/political) tone in the opening credits: “Dedicated to all those who fought and suffered in the Salient and to the memory of our comrades who sleep beneath that ‘foreign field that is for ever England.’” The citation of Rupert Brooke, famous both for his enthusiasm for the war and for his early death (en route for Gallipoli) in 1915, indicates the tenor of what follows. How immortal is this film’s story? Well, very immortal, according to the first narrational title: “The immortal story of the Ypres Salient begins in October 1914. Indomitable Belgium, wrested of all save her immortal soul, resounds to the heavy tread of the invader’s heel.” Yes, we’ve got a double helping of immortality, plus a side portion of indomitability. Let’s just hope the invader’s heel doesn’t step on our metaphor! Come on, chums, let’s up and at ’em!

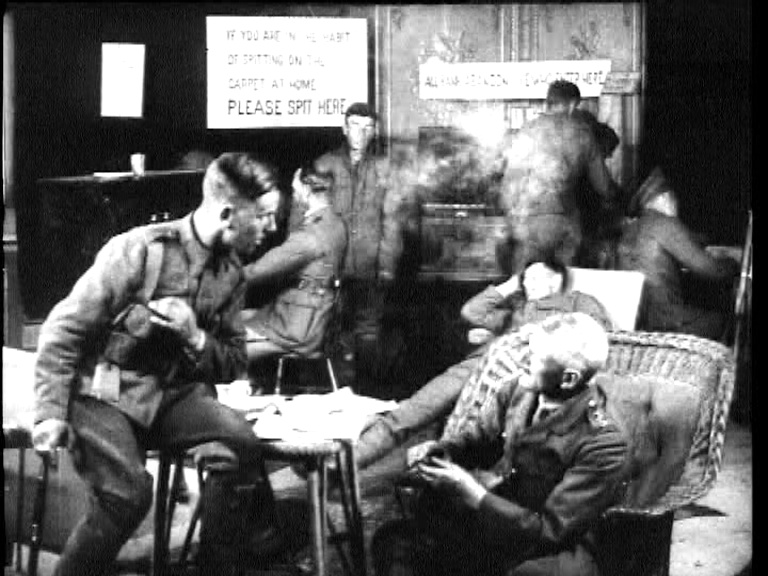

The tone of intertitles suggests how the film seeks to humanize the Allied soldiers (and nurses) and demonize the Germans. The Germans are “field-grey hordes” while the Belgian civilians are “the innocent and helpless victims of War’s ruthlessness” (see also “Sister Marguerite and her band of heroic nuns”). The British Expeditionary Force (BEF) arrives “laughing and singing” in Ypres, while the Germans are reduced to often distant ranks of fodder for their guns and cold steel. The first time we see much of the Germans at close quarters, they are in their dugout boozing and raucously playing the accordion – while outside brave Tommies with blackened faces launch a deadly raid on their position. “Is anybody in there?” a British soldier yells down the staircase to the dugout. “Nein – nein!” the accordionist shouts back. “NINE did yer say, well share this amongst yer!” Tommy throws a grenade into the dugout. It explodes inches from the group of Germans. It neither kills nor wounds any of them, but up they come to the trench, trembling like lambs.

The film is bloodthirsty while being curiously reticent to show us any actual blood. In this way, the film recreates many heroic deeds, often those that earned the Victoria Cross (the highest military award) for bravery. For example, we see a Canadian officer lead his men forward with sword in hand. He is shot down (without spilling a drop of blood), whereupon a title announces: “His is no wasted death. Spurred to vengeance by their leader’s fall, the Canadians surge forward in one headlong rush, capturing their objective and bayoneting every defender.” Lovely, though we don’t see the orgy of bayoneting the title promises. Likewise, we see heroically outnumbered British machine-guns blaze away at point blank range but nobody German falls down dead in front of it. (Later, another heroic machine-gunner’s frightful toll is unseen apart from three or four hapless Huns.)

The film also has a curious interest in immortalizing “unknown” deeds. Thus we see a chaplain making a brave crossing of a shelled road, after which a title says: “The Padre received no reward for his action, but like countless others he had the satisfaction of knowing that he had done his duty.” Elsewhere, there is a similar incident of a cook bringing rations to a company through shot and hell: “You won’t read of their deeds in the History books, / But they’re deuced fine chaps are the Company cooks.” Of course, we are privileged to see these unseen events. The film is allowing us both a public history (of celebrated heroes) and an obscure one (of uncelebrated heroes).

Other methods to humanize the nameless Tommies come in the form of comic scenes. There is a bustling bathing scene, complete with comic asides from plucky lads keeping their spirits up in hard times, as well as scenes of behind-the-lines entertainments. There is also one scene of a soldier going home to his little house, his little wife, and his little blonde child. It’s all weirdly uninvolving. That is, except for the lovely image of the soldier’s house: here are the flowers and trees of a century ago, blowing in the wind. It’s beautiful, captivating – and the film takes no time to emphasize it.

The third battle of Ypres was (in)famously fought over waterlogged terrain in which men frequently drowned. How does the film handle this most famous of features? “With the night the weather changes and the fighting is continued in heavy rain”, we are warned. But there is no rain on screen. The opening phase of the battle skips over such details thus: “In spite of all handicaps, a considerable advance is made, and over 6000 prisoners taken.” No maps show us just how “considerable” this advance was, nor are the “handicaps” shown. Immediately, though “the weather grows steadily worse, and despite superhuman efforts the advance is laboriously slow.” What do we see of this? Well, there is some inane and unconvincing hand-to-hand combat by a small stream. (A self-contained stream that has not burst its banks.) We see tanks easily crossing the battlefield, the only water a couple of puddles. To skip to the end, the last title sums it all up thus: “In a war of heroic deeds, Passchendaele will rank among the most heroic struggles. On 7th December, after five months of gruelling fighting, the crest of that tragically famous ridge is gained.” (The film does not over the fighting of 1918, in which the right was lost again – then rewon, all at the price of many tens of thousands more casualties.)

If all I’ve done is point out the crudeness of the film’s tone and dramatic method, I must conclude by saying that cinematically it is well put together. The photography is strong with frequent and effective use of soldiers silhouetted against large northern skies. There are few close-ups, which makes the use of anything closer than medium or long shots striking. More often than not this is used for the comic scenes, which are less interesting. But there are some effective uses of single soldiers positioned away from the massed ranks/groups that work well. (The image of an exhausted soldier with cigarette in mouth, standing in the foreground while ranks march past behind him, is very striking – it’s not surprisingly that the image is used by the BFI to advertise the streamed version of the film.)

There are also various models and matte painting used to good effect, though nothing very complex. The first glimpse of Ypres is a matte painting, nicely framed, while there are some models to use for the destruction of a zeppelin. For the latter, Summers wisely chooses to stage his aerial fight at night, the dark lending a hand to make the lack of real footage or locations less obvious. Summers also uses plenty of men and materiel to good effect, always filling his frame with people – or else masking portions off with the scenery or smoke and explosions. He also uses some limited amount of newsreel footage shot during the war. But he’s also canny enough not to use any of the real battlefield: it would entirely upstage and undermine the simple heroics of his own “docudrama”. You can’t show the horrors and destruction of the real battlefield if what you’re selling your audience is a boy’s own adventure version of history – albeit a well-equipped one. It’s a very clear and logical film, well put together. But it isn’t reality.

Finally, a note on the DVD edition by Strike Force Entertainment. Unlike the version on BFI Player, this presentation has a soundtrack. The back of the box announces: “The original silent documentary has had an all new soundtrack created from digitally enhanced recordings of the period as well as the addition of evocative sound effects.” Without digital enhancement, anyone nearby would have been able to hear my heart sinking as I read these words. However, the end result is not so bad. It’s a mishmash of musical fragments, united only (I assume) by the fact that they are free of copyright and can thus be chopped and changed per the arranger’s wish. There are also plenty of sound effects, which are far too “new” to my ear, so they stand out a mile from the aesthetic (and historicity) of the film and the acoustics of the musical samples. But I can’t deny that it’s better than I feared. It’s serviceable.

Mons (1926; UK; Walter Summers). On to Mons, which was one of the pivotal early battles of 1914. The BEF was retreating across Belgium, pursued by the much larger German forces. Mons was a “fighting retreat” in the last glimmers of “open warfare” that would soon be replaced by the static trench warfare. It was seen as a test of the strengths of Britain old, professional army – the army that was soon to be worn out and replaced by the waves of volunteers and conscriptions. The original BEF became known as the “Old Contemptibles”.

“Dedicated to the memory of the Old Army which came triumphant through a great ordeal and gave a new and noble meaning to the word ‘Contemptible’.” Thus the opening title. There follows a confusing and ill-explained (actually, entirely unexplained) scene between (unnamed) old politicians arguing about the validity of war. Cut to a mix of newsreel and fictional footage of British troops embarking for the continent. From this point, the action is better narrated. The progress of the armies is described in enough detail to follow, though (unlike Ypres) there are no detailed maps to put everything in place. In a way, it suits the hectic nature of the mobile front to be unbalanced in this way.

And the representation of the fighting? Well, there are cavalry charges and unconvincing firefights and scores of German prisoners, helpless at the sight of cold steel. There are heroic deeds and selfless sacrifices. There are cutaways to Germans admitting how they’ve underestimated their enemy. (“Why not admit it? Our first battle is a heavy – a very heavy – defeat. And that defeat inflicted by the English, the English whom we laughed at.”) There are endless contrasts between the smallness of the British and the masses of the Germans. (“Shatter their ranks, they are filled again. Mow them down in thousands, from the dragon’s teeth spring more.”) There are fewer overtly “comic” scenes than in Ypres, but there are several vignettes to concentrate on individuals. There is “the straggler” who gets marooned with a wounded comrade in a windmill and fights of German uhlans. There is an officer who buys a child’s drum and fife from a local shop in order to rouse his men with any kind of martial music. (The scene ends with a vision of a Victorian band in full regalia playing them on.) Then there’s the scene where a lone British soldier encounters a lone uhlan at rest. The soldier is armed but is too chivalrous to take the German’s possessions without a fight. So they take off their tunics and box, until the German is (of course) knocked out cold.

By dint of its setting in open warfare, and in summer, Mons has more chance for wide, expansive images of the landscape than in Ypres. Summers again makes great use of horizons and silhouettes, of great masses of troops, of racing horses, of mobile batteries, of bridges and brooks, of explosions filling the screen. There are one or two tracking shots, and even a rapid panning shot, which help variate the rhythm of the scenes (many of which are much of a muchness).

And the meaning of it all? According to the last title: “The Great Retreat is ended – the Great Advance, which is to end in ultimate victory, begins.” Describing the onset of static warfare and years of unimaginable suffering and appalling losses as “the Great Advance” is… well, what is it? I genuinely can’t think to express my feelings at this point. They grow more complex, and I will reserve judgement until after the next film…

The Somme (1927; UK; M.A. Wetherall). Right, the final film, and the one that covers one of the bloodiest battles in human history. Between July and November 1916, the British & Commonwealth and French armies launched an offensive on either side of the river Somme. In five months of attritional fighting, the Allies advanced barely six miles and lost over 600,000 casualties. The Germans lost somewhere over 500,000 casualties. The BFI Player notes for this film begin: “This sophisticated retelling of the Battle of the Somme includes an outstanding montage ‘over the top’ sequence.” Fine. What else? This production was “principally the brainchild of Geoffrey Barkas and writer Boyd Cable (Ernest Ewart), both of whom were at the Somme”. Barkas was the original director, but he fell ill and was replaced by M.A. Wetherall. So then, a film produced by veterans with an outstanding over the top sequence. Bring it on…

Hmm. Well, the quality of this print is by far the worst of the BIF films that are offered by the BFI. (The clips from The Somme included in Brownlow’s documentary series Cinema Europe are clearly from a better source print (and tinted, too), and the episode that covers the film also include an interview with one of its cameramen, Freddie Young.)

What enthusiasm I can still muster for such a grotty copy of the film is steadily quashed by its treatment of war. Here are the Germans in their dugouts, laughing at the image of the Britishers. Here are comic asides by the British tunnellers, planting tons of explosives beneath the laughing Huns (“He’ll want an aeroplane for a hearse when this lot goes up!”) The Somme is filled with deeds without drama, with soldiers without subjectivity, with action without aftermath. This is not to downplay the film’s technical sophistication. Some striking images are achieved through double-exposure/matte painting combinations that mimic the explosions on the horizon as troops march towards the front. (Tinted, the effect would be much better.) But my interest in all this bustle on screen is without heart.

The “over the top” sequence is perhaps the only real effort to create dramatic tension through a complex use of imagery. We see the final minute of time before the whistle blow unfold in real time. Superimposed over the image of a clockface, we see images of the waiting men: biting nails, tapping feet, poised at the ready. It’s an oddly protracted scene of tension. What it undoubtedly possesses in cinematic flair it lacks in dramatic design. This period of waiting is not associated with any particular character or characters. We do not know any of the people we see waiting: they are unnamed figures that we have not met before don’t meet again. We can’t feel anything more than a rather abstract or generalized feeling of tension. Despite the realities the film attempts to show, and despite the reality of the seconds ticking by to Zero-hour, these aren’t real human beings on screen – and I simply didn’t feel properly involved.

Finally, the text “ZERO” grows in size to occupy the screen. Over the top! But what happens next is a quite shamelessly whitewashed depiction of the first day of the battle. To remind you all, the British & Commonwealth forces lost nearly 60,000 men for almost no ground gained. Instead, The Somme provides us with reassuring text about territorial gains and advancing guns – and no mention of objectives, casualties, expectations, consequences. The battle goes on. There are scenes of senior officers discussing plans, scenes that are stiff and awkward in the extreme. They are there for illustrative purposes, but what – really – are they illustrating? The figures aren’t named, they don’t have identities, motives; they have no function other than to gesture towards a chain of command and a strategic process that the film has no ability or interest to explore.

The film is more interested in the lower ranks, but what kind of justice does it do to their struggles? We see heroic deeds, lone pipers playing under gunfire, the wounded being rescued. But where are the bodies? We’re told in one title that two waves of an attack were mown down by machine gun and rifle fire. Instead of showing us this, the title immediately dissolves onto a second title, reassuring us that the third wave – inspired by an officer’s hunting horn – went over the top and succeeded.

The film knows it cannot deny the sacrifices made, but it also cannot bear to show them or name them. We are shown maps of the battle, but they do not show the objectives in relation to the initial timetable (positions that were meant to be taken on day one were still out of reach months into the battle). A later title implies the difficulties the Allies faced without making them explicit. Here, the text mentions Beaumont Hamel, “where our attacks had broken down with such appalling losses on 1st July” but where “the enemy still remained secure”. Where were these “appalling losses” in the relevant part of the film? Where even was anything shown to “break down”?

The film then blames the weather for stalling an inevitable victory. Here, we see some of the few instances of the troops occupied not with heroic deeds or plucky comedy but with forbearance – and even, in one scene, expressing something like fury. This comes in the form of a remarkable shot of a soldier lying in mud, delivering an untitled monologue; but anyone who can lipread even slightly will pick up phrase like “fucking war” and “fucking mud”. What to make of this? It is the only voice (but “voice” is somehow an inappropriate term in this silent scene) in the entire film raised against the tone of patriotic success. But the film cannot, dare not, follow it up or elaborate on it. Another soldier witnesses this outburst, but he carries on without comment. So does the film. A title later states: “the weather closed down like a curtain upon a glorious tragedy”. Glorious tragedy is it, now? Well, the film manages to win a victory nevertheless by skipping forward to the German tactical retreat to the Hindenburg Line in early 1917. “The sacrifice had not been in vain.” These words are spelled out over a vision of a scarred swathe of land, the remains of an advance scattered over the torn ground. But there are no bodies, no victims, in the frame. It is as if the “sacrifice” is too great to show and has already been tidied away.

I suppose by this point I had grown weary of these BIF films. But there was something in the evasiveness and hypocrisy of The Somme that especially irritated and upset me. The film retrospectively mentions horrific casualties and abject failures yet never once depicts them. It depicts heroism without placing it in the context that makes it heroic. We see just one blinded soldier, fumbling in a crater. We see just one voice raised against the appalling conditions, but his voice is un-transliterated. Nothing is questioned; everything is justified. The Somme is a film that has neither the interest nor capacity to think about what it shows us, let alone to feel something. It is a spiritual and moral vacuum.

To conclude this overlong piece, I do not regret going through these BIF films. They form an important genre of popular commercial filmmaking in the UK in the 1920s. But in all honesty, I cannot wait to watch something else, something more honest – in whatever genre. To repeat what I said in my earlier piece, these BIF films offer exciting visions of the Great War that may impress by their scale and vigour but frustrate by their utter disinterest in real human beings or real human emotions. For films dealing with industrialized slaughter, it is quite staggering how little there is on screen of genuine consequence. It is also worth repeating the citation I offered last time from Bryher, writing in in Close Up in October 1927. Illustrating that even people at the time might feel queasy watching these films, Bryher attacked these BIF productions for their dishonest treatment of war:

There are plenty of guns and even corpses in the British pictures but the psychological effect of warfare is blotted away; men shoot and walk and make jokes in the best boy’s annual tradition and that some drop in a heap doesn’t seem to matter because one feels that in a moment the whistle will sound and they will all jump up again…

I am likewise left deeply uneasy about these films. Indeed, I also take it that the way the BIF productions have been treated by the BFI suggests some similar qualms about the rationale for their restoration and exhibition. Of course, The Battle of the Somme (1916) – made while the battle was still raging in the summer of 1916 – is a famous example of wartime reporting that has been restored more than once and has long been available. It may not show the full horrors of the battle, but it has enough glimpses of real injury and real death to make it shocking – then and now. The Battle of the Somme is an extraordinary document of its time, but the reality of those faces still reaches out to us in the present; the film is naturally much seen and studied. Conversely, the BIF films – despite being more numerous and just as popular – are relatively obscure. Asthe only such production to have been fully restored and released in the modern era by the BFI, I wonder how many university courses include The Battles of Coronel and Falkland Islands? Of all the BIF films, it strikes me it is the one most palatable to modern audiences. In treating a sea battle in which the total losses were less than 4000 lives, it is less likely to seem an inappropriate mode of representation. With Mons, there is an appealing vigour in its treatment of a series of dramatic encounters in the open warfare of 1914. But with Ypres and The Somme, I cannot imagine the propagandist treatment of the bloodiest battles in British & Commonwealth history going down so well.

Of course these films are “of their time”. But is that also an excuse to avoid looking at what they represent, or at what uncomfortable resonances they might still have? As Bryher’s review makes clear, some critics could and did feel differently even in the 1920s. She herself made the link to the rise of nationalism and fascism across Europe, forces that relied on images of a glorious military past and of war as a heroic pursuit. One might also look to France and to Léon Poirier’s Verdun, visions d’histoire (1928), which is a far more melancholy look at another critical battle of the Great War. As it happens, for all its cast and resources, Verdun is an absolute bore of a film – like an illustrated lecture, only weirdly portentous. Yet it still transcends the jingoist tone of the contemporary BIF productions. Poirier’s film even tries to address the spiritual aftereffects of war, to acknowledge that the millions of men who fought and died had value beyond their actions on the battlefield – that they were all, equally, human beings. There is more to be said about films like the BIF production in comparison to Soviet “history” films of the 1920s, as well as with more straightlaced films like Verdun, but frankly I’ve had enough of this genre for a while.

Paul Cuff