This week, I return to the new restoration of Abel Gance’s Napoléon (1927) by the Cinémathèque française. I saw the premiere of this version with live orchestra in Paris in July 2024, but now I have the opportunity to pour over it on the small screen. Yes, the restoration has finally been released on UHD, Blu-ray, and DVD formats in France by Potemkine. What follows is not so much a technical review, especially since I do not have the wherewithal to play – let alone analyse – the UHD discs of this edition. Instead, I want to comment on how the Blu-rays reveal some of the choices made during the restoration process. Though it was broadcast on French television in November last year, this is the first time I have been able to see it in detail. At home, I can pause, replay, and capture. While the sense of live drama so palpable in the Paris concert cannot be replicated at home, other aspects are perhaps more evident through analysis on the small screen…

Presentation. As befits the ballyhoo around this restoration, the box is pleasingly hefty. Indeed, it rather resembles a Kubrickian obelisk. And, like our prehistoric ancestors, it took me several minutes of examination and careful fondling to work out how to open the damn thing. But I can’t deny that it’s a lovely object to observe and to handle. Inside are 1) a fold-out box of the UHD and Blu-ray versions of the film, 2) a small booklet discussing the music and listing Gance’s cast/crew, and 3) the Table Ronde book from 2024 that contains a series of essays by various people involved in the restoration, as well as historians analysing the film. The booklet contains very little material that hasn’t been included elsewhere before, and the Table Ronde book was released in exactly the same format as a separate publication last year. (On this, see my earlier review.)

On the discs themselves, I immediately flag an issue that may concern non-French speaking readers of this blog. The Potemkine edition has no subtitles of any kind on any of its presentations. This is despite press releases promising (at the very least) English options for any/all formats of this edition (DVD, Blu-ray, UHD). Furthermore, the restoration end credits include a list of translators for six foreign subtitle tracks. None of these are listed on the packaging, and I checked on the Potemkine website and various other retail outlets in France to confirm: there is no mention of subtitles. I can only assume that this was due to copyright reasons, as it is commercial folly to reduce your potential foreign sales by not offering more language options. I’ve not yet heard about any plans for the film’s international release, either via Netflix or any other means. I can only imagine that one or more interested parties don’t like the idea of an English-language home media edition of this film preceding a future release. Though the Table Ronde publication makes the claim for the Cinémathèque française possessing worldwide copyright for Napoléon, there are clearly limits as to how and when it is being sold to international territories. Since I began writing this review, news has emerged that Potemkine (and other retailers) have begun cancelling orders to anyone outside France. Merry Christmas, everyone!

Image. Something I had not properly appreciated at the film concert in Paris was the was the Cinémathèque française sought to digitally simulate the look of Napoléon as it might have been projected on screen in 1927. This involves simulating the relative brightness of the projection lamp, as well as the framing of the image as projected on the screen itself. Watching the Blu-ray, these choices are much more striking.

In terms of the relative brightness, projector lamps of 1927 were not only powered by different means but ultimately less luminous than a modern equivalent. A simulation of this difference involves filtering the restored video to make it look warmer than it would otherwise appear. Restorers are always conscious about digitally recreating the “look” of a silent film that was shot on celluloid, but the issue of projected brightness is less discussed. However, the effort to adjust the look of Napoléon this way has at least one recent precedent. The 2019 restoration of Gance’s La Roue (1923) by François Ede and the Cinémathèque française made a conscious effort to reproduce the look of the film as projected in 1923. (You can see images from this restoration on my post from last year.) Apparent to anyone who saw previous editions of La Roue, either projected on 35mm (on modern projectors!) or digitally reproduced on DVD, Ede’s choice gave the extensive black-and-white photography of this film a much warmer look than before. This results in black-and-white no longer being… well, black-and-white. For monochrome scenes (the majority of the film), it’s like an ochre wash has permeated the frame. It will also influence tinted/toned sequences, though the interaction of this filtered brightness with colour elements is more difficult to unpick.

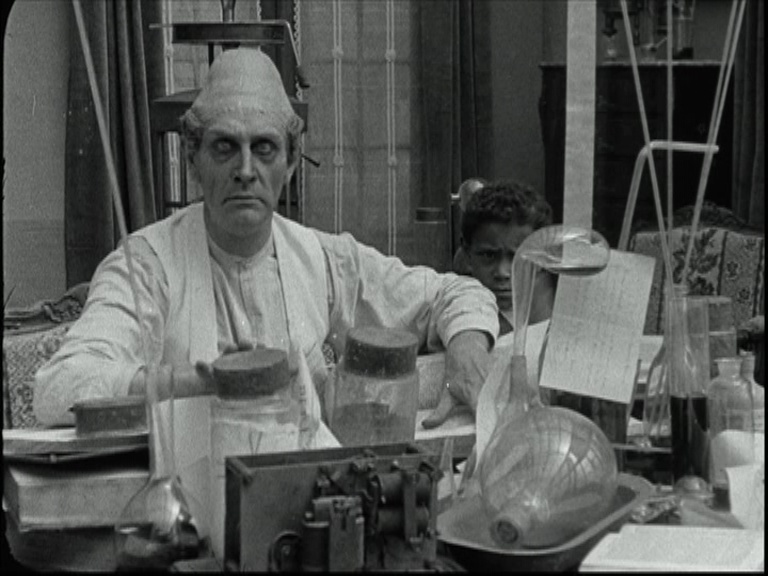

All of which is to say that the black-and-white sequences of Napoléon also look less black-and-white than in previous editions. This is most obvious (and, to my eyes, most aesthetically counter-intuitive) in the prologue, where the snow in the snow-covered landscape now looks decidedly less clean. On the big screen in 2024, I think my eyes adjusted to this – though there was so much light spill from the orchestra that the contrast was hardly the best anyway. On the small screen, I notice the aesthetics of this simulated warmth (I can’t quite call it “dimness”, but that it surely part of it) on the Blu-ray much more. Ede explained his reasoning for this choice about brightness in the liner notes for the Blu-ray of La Roue in 2019, by far the best and most transparent set of notes for a restoration I have ever read in this format. There are no such explanatory notes on the Cinémathèque française release of Napoléon, so it’s worth saying again: these scenes are not tinted or toned; they are monochrome black-and-white, purposefully rendered less so.

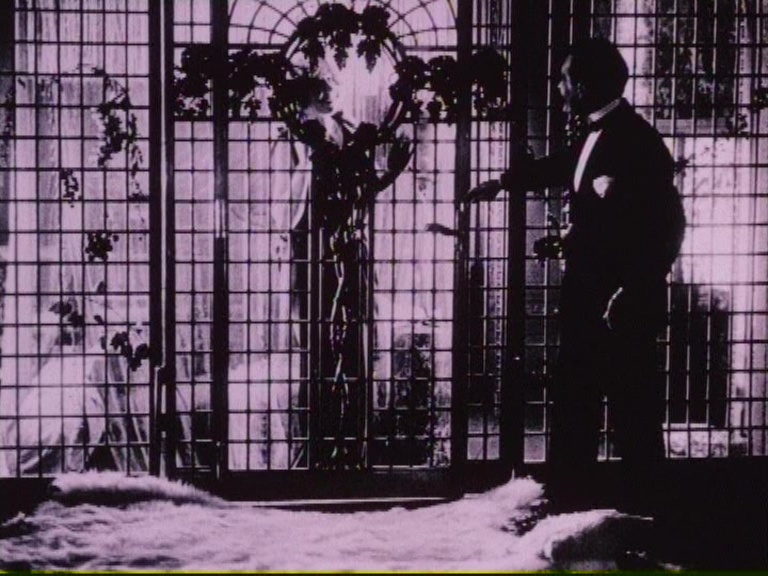

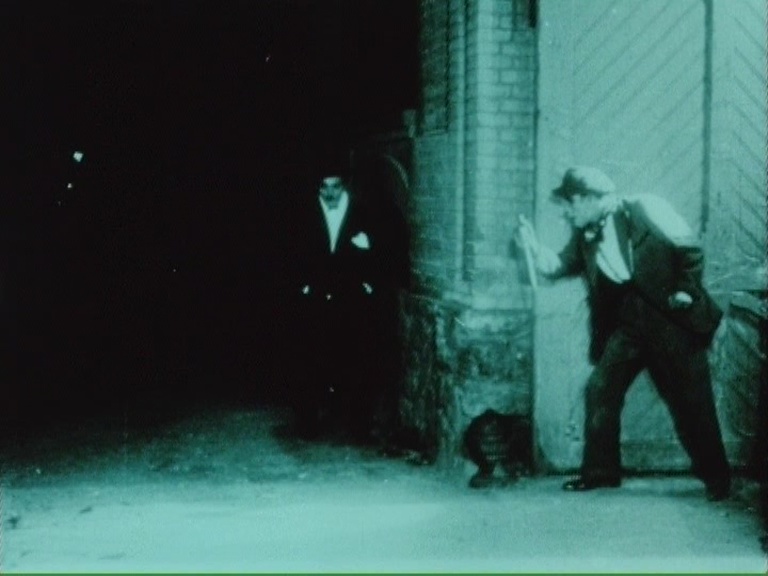

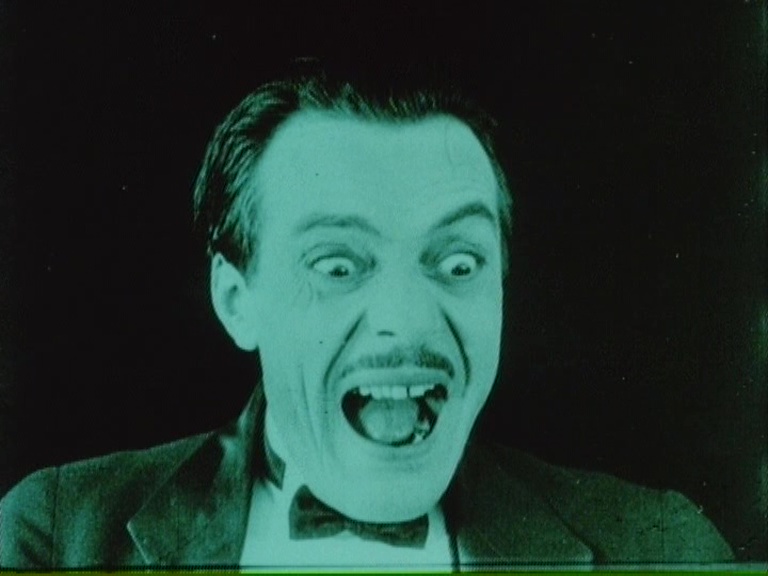

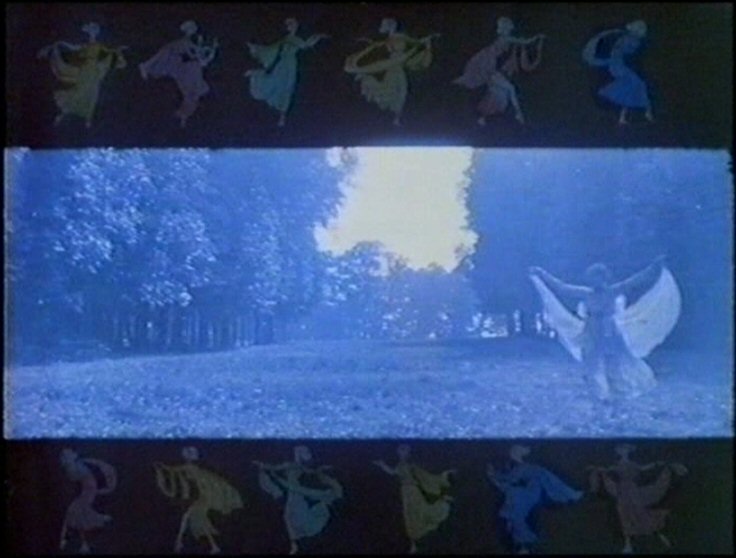

In terms of framing, the Cinémathèque française went one step further with Napoléon than with La Roue. According to their analysis, the aperture of contemporary projectors would slightly crop the film image on all four sides of the frame. As the below captures illustrate, there is less information within the frame in the 2024 restoration than in the BFI’s 2016 restoration. This is very noticeable as soon as you compare identical frames from identical shots between versions. I don’t have the time or energy to offer dozens of examples. (It is complicated by the fact that different restorations have utilized material from different versions of the film, so finding identical shots is rather time consuming!) But the final triptych is a clear example of how images deriving from the same negative (originally included in the Opéra version and subsequently added to some presentations of the (shortened) Apollo version) look different due to choices of the restorers. First is an image from the BFI’s 2016 restoration, second one from the new Cinémathèque française restoration:

I simply don’t know what to think about either of these choices. I understand and respect absolutely the desire to be historically informed, though it is ultimately impossible to ensure absolute fidelity to lost practices. Accuracy is also difficult to guarantee in a realm where there was enormous diversity across cinemas and equipment. Even this “fixed” digital image will look different on every screen that it is seen – projected or otherwise – in 2025. This is not to say that any desire to emulate the aesthetic of projection in 1927 is wrongheaded; it isn’t. But it is an irony that this restoration, which seeks to reveal Gance’s masterpiece in its ideal form, also takes steps to restrict the boundaries of its images.

It is also curious that Napoléon has been chosen to be presented in this way, but not other contemporary films produced by the same company, the Société Générale de Films (SGF). Gaumont’s recent restorations of La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1928) and Finis terrae (1929) do not feature the cropping or dimming undertaken on Napoléon. You can see the edges of the frames in these other films, and the black-and-white is… well, black-and-white. Does Napoléon particularly benefit from extra treatment? If so, why? Or are we to take it that Gaumont’s restorations are somehow inaccurate, or at least ahistoric? I would perhaps have fewer qualms if the choices made during this restoration of Napoléon were in any way detailed, clarified, or explained in the accompanying booklet. But they are not.

The extras. To better illustrate the above issues, I can do no better than turn to one of the extras on the Blu-ray edition. Autour de Napoléon (1928) is a documentary made by Jean Arroy during the filming of Napoléon in 1925-26. It boasts some extraordinary behind-the-scenes footage of the production, both during and in-between shooting, as well as extracts of Napoléon itself. Extracts from Arroy’s remarkable film have previously featured in various modern documentaries on Gance and/or Napoléon, but this is the first time the surviving material has been assembled into a coherent whole. Alas, this restoration of Autour de Napoléon does not state how long it is, nor how this compares to the film’s original length in 1928. (Nor does it state what framerate(s) it uses.) However, information from 1928 does survive in the archives, so I can report that the film was originally shown in a version of 1605m, which would be approximately 70 minutes at 20fps (or 78 minutes at 18fps). At just less than one hour, this 2025 reconstruction at least presents most of the film. And, unlike the opening credits of Napoléon, it admits that the original montage is lost and cannot be definitively recreated with existing material.

Autour de Napoléon was restored by Eric Lange, with the assistance of Joël Daire, Serge Bromberg, and Kevin Brownlow. The restoration was produced by FPA France (the successor company to Lobster), though in association with the Cinémathèque française. What is immediately striking about this presentation of Autour de Napoléon is that it does not feature either the re-adjusted monochrome or frame cropping of Napoléon. This is most obvious when Autour de Napoléon includes extracts from Gance’s film. Though the footage used by Arroy seemingly derives from both the Opéra and Apollo versions of the film, certain shots are identical to those found in the Cinémathèque française restoration of Napoléon. In these examples, the full frame is visible, and the monochrome is more obviously black-and-white. (The tinted scenes are also far less saturated.) Though the original material (derived from several sources) for Autour de Napoléon is clearly less well preserved than for Napoléon, the difference in what is seen on screen is significant. In the below image captures, those from (the FPA France) Autour de Napoléon are on the left and those from (the Cinémathèque française) Napoléon on the right:

But these aesthetic issues are secondary to the sheer joy of watching Autour de Napoléon. The footage of Gance and his crew filming Napoléon is astonishing. You can see the unbelievable lengths they went to in order to achieve visual mobility: we see the camera mounted on a sledge-propelled guillotine, strapped to an operator’s chest, run on cables from the ceiling, mounted on the back of trucks and of horses. What’s more, the camera so often had to be specially mechanized to turn without being cranked by hand. Witness the amazing sight of Gance and his crew standing to admire the camera turning 360 degrees on its tripod, as if it were a living thing.

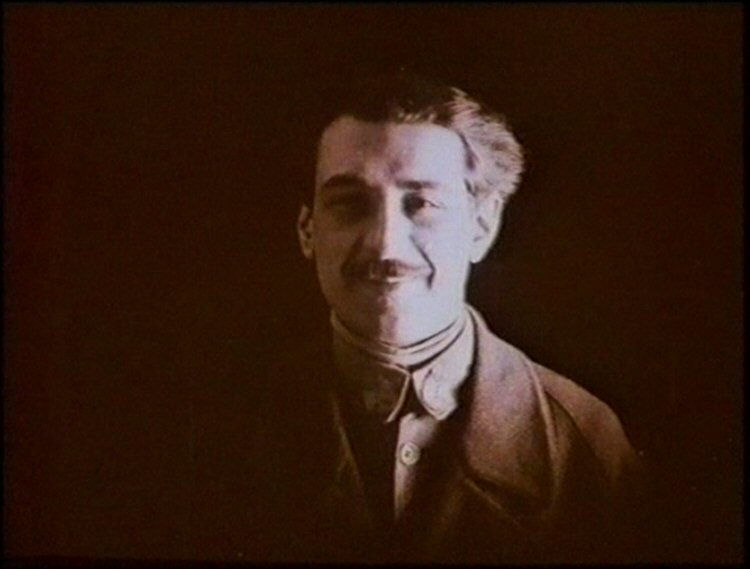

None of this would be so impressive if it weren’t for the evident energy of the entire cast and crew at work. Quite simply, Autour de Napoléon is one of the most joyful records of filmmaking you’ll ever see. Immediately striking is the sheer fun these people are having making this film. Gance – as Bonaparte is described in the prologue of Napoléon – is everywhere. Here he is in the snow, urging on the children in their snowball fight, and urging on his cameraman Jules Kruger to capture the action. Here he is demonstrating a gesture to his young Bonaparte, a gesture we will see exactly reproduced by the actor in the film itself. Here he is with an enormous megaphone, poised to direct the huge crowd that fills the set of the Convention. Here he is with a revolver, firing in the air to create the shock and fear he wants from his performers…

What’s so striking is how playful Gance is on camera. At a distance, we see him intensely concentrating on the activity on set. But when he’s close by, he’s always got an eye for the camera – for us – and he plays up to it wonderfully. Here he is in a huddle with Annabella and Gina Manès, playing with Josephine’s dog, making everyone laugh. I love these in-between moments of silliness. You get such a sense of the mood on set, such wonderful glimpses of these long-dead artists caught in the midst of life. By contrast, I think of the forbidding Marcel L’Herbier on set in Jean Dréville’s later making-of documentary Autour de l’Argent (1929). Here, L’Herbier never takes off his impenetrable sunglasses that shield him from the studio lights – and from our gaze. He’s a faintly sinister presence, always at work and never at play. (Kevin Brownlow once told me that meeting L’Herbier was like encountering an aristocrat from before the Revolution.) Dréville’s film is far more polished than Arroy’s, but it entirely lacks the fascinating odds and ends of Autour de Napoléon. See how much in-between time there is on screen. We see cast and crew relaxing on Corsica, meeting the locals; we see them waiting for the action to resume, or killing time when things ground to a halt. Arroy has an eye for the comic and incongruous. Here is a troupe of cavalry led by Bonaparte, who happens to be driving a car down the street. Here is Bonaparte, pistol in hand, sat on the back of another car. Simon Feldman, Gance’s Russian technical director, leans over the side, smoking a small cigar. They are waiting for a train to pass before they can resume filming. In the background stands a group of Pozzo’s frustrated cavalry. Gance is there too with Jules Kruger, who holds his huge handheld camera on his shoulder. The train slowly trundles past. As it does so, Gance sees that Arroy is filming and stalks towards the camera. He comes up to the back of the car and goes “Boo!”, throwing forward his arm. Arroy cuts to the next scene. It’s such a lovely moment, one of many rendered incredibly human by their incidental nature. That this film exists is miraculous, and I’m incredibly pleased and moved to finally be able to see so much of it. On this edition, Neil Brand provides a lively and fitting accompaniment on the piano. A superb extra.

Next up is Abel Gance et son Napoléon (1984), an hour-long documentary by Nelly Kaplan. This includes fragments of Autour de Napoléon, together with narration by Michel Drucker, who also appears at intervals in the former Billancourt studios where Gance filmed in 1925-26. Kaplan was Gance’s artistic (and personal) collaborator in the 1950s and early 1960s, as well as a much respected filmmaker in her own right in later years. It’s a shame, therefore, that she herself does not feature as a subject in this film. I recall seeing Kaplan for the last time in 2015, when she made an appearance at the Cinémathèque française during a presentation by Mourier about Napoléon. This included an extract from Abel Gance et son Napoléon, and when Michel Drucker appeared on screen much of the auditorium started laughing. Such is Drucker’s reputation as a cheesy host from French television in the 1980s. I felt very sorry for Kaplan, who was otherwise largely ignored at this event. One suspects that the inclusion of her Abel Gance et son Napoléon on this new Blu-ray is a mark of respect more than a measure of the documentary’s importance. Next to Autour de Napoléon, it is unfortunately rather thin.

Elsewhere, we get La Saga du Napoléon d’Abel Gance (2025) an hour-long documentary by Georges Mourier. It covers the story of the restoration, as well as the memories of some of Gance’s surviving friends and relatives. It’s lovely how Mourier plays with the age of his interviewees, showing them juxtaposed, young and old in a variety of archive (and new) footage – demonstrating the years that have passed, the time taken for this project to be envisioned and realized. I also found it very endearing to see Mourier and his colleague Laure Marchaut at work, and to see them age across the film. It’s a testament to their decades-long devotion that this documentary captures the effects of time on its human subjects as well as the film itself.

Of course, I was also longing to hear more information on the choices of the restoration, but that is not provided here. It’s very much geared to the story of the search across the globe for every last copy of Napoléon, and of the discovery of the “Rosetta Stone” in the archives: the document that details the scene-by-scene breakdown of the original Apollo version of 12,961m. But the history of how and when the Cinémathèque française decided to reconstruct the later, shorter edition of the Apollo version – “la Grande Version” – is not discussed. Nor is when and why this version was deemed “la Grande Version”, nor how its contents were determined, nor if other material survives that was excluded from the restoration, nor how closely the restoration resembles the original “Grande Version” in length or structure. As I outlined in detail in my previous posts on the new restoration, these questions remain unanswered. And since neither the credits, book, nor indeed any source mentions it, I did a quick time check. Excluding the lengthy restoration credits, this version of Napoléon runs to 6hrs, 59min, 37sec. At 18fps, this indicates a projected length of approx. 8633m – another figure not mentioned anywhere in the literature.

(I must also record my amusement at some of Mourier’s musical choices on the soundtrack of his documentary. He uses Beethoven’s Symphony No. 6 to accompany a clip of the “Double Tempest”, just as he uses sections of the same composer’s Symphony No. 7 and Coriolan Overture to show other scenes of the Revolution being reassembled. These are the exact pieces used by Carl Davis in his score for the film, per the BFI edition. It’s interesting that Mourier seems to prefer Davis’s choices than Cloquet-Lafollye’s choices, which form the soundtrack of the Cinémathèque française restoration but do not feature in this documentary. Hmm.)

There are also three videos from film historians. In “Napoléon au cinema”, David Chanteranne talks about Gance’s film in relation to other cinematic Bonapartes, and to Napoleonic iconography more generally. The other two videos are by Elodie Tamayo. I have sung her praises in earlier posts, as her work editing Gance’s correspondence and resurrecting the fragments of his Ecce Homo (1918) is of enormous value. For this release of Napoléon, there is an interview with her and a video essay featuring clips from Gance’s film itself. Both are extremely engaging, interesting, and – especially the video essay (“Napoléon à contre-jour”) – beautifully thought-through presentations. She discusses the film’s relationship with history, with Gance’s ideology, and with the medium of cinema itself. Her analysis manages to get to the heart of this enormously long film in an impressively brief space of time. (And I speak as someone who spent 332 minutes commentating on the BFI Blu-ray and still worries I didn’t do enough!) I earnestly hope that we hear more from Tamayo on Gance in the future…

Those are the sum of the extras, but I can’t help feeling that there are many more than might have been included. Most obviously, the Opéra version of Napoléon would have made a fascinating comparison piece. For all Mourier has emphasized that this was inferior to the Apollo version, it would be nice to see the difference for ourselves. If nothing else, it is of tremendous historical significance as the first version of the film shown in public. But I can also understand why this version might not have been included, aside from its four-hour length – and the expense of producing it. Its inclusion would inevitably signal that other versions of Napoléon might be interesting, valid, and valuable iterations of Gance’s project. This would rather jar against the label “definitive” that has been appended to the marketing for the restoration. Releasing the Opéra version would also demonstrate the fact that the triptych version of the “Double Tempest” it once boasted remains missing, and this fact might also raise awkward questions about the restoration process, its decisions, motives, and outcomes.

Another absence is the single-screen ending of Napoléon, as included in the original Apollo version – and in subsequent screenings at cinemas that lacked the capacity to project the triptychs (i.e. most cinemas). (Thankfully, this alternate ending is included on the BFI release as an extra.) Also absent are the triptych “studies” that Gance produced in 1927 using footage from Napoléon, short films which were subsequently projected at Studio 28. Two of these, Danses and Galops, have been restored and were shown at the Gance retrospective at the Cinémathèque française last year. (Sadly, this was a screening I couldn’t attend.) The third of Gance’s studies, Marine, is seemingly lost – a great shame, as it was purportedly the most visually beautiful of the three. Any material from or relating to these short films would have been a great bonus. Will they ever get a home media release?

Finally, I must admit my chagrin at the only book included in this set being the Table Ronde publication. I had thought that Mourier might have contributed a more substantial written account of the restoration. He announced some time ago that he would be publishing a book on his work on Napoléon, and I hoped that it would be included with the Blu-ray edition. Sadly, I must wait to give the Cinémathèque française yet more of my money. I do hope the book includes more evidence of the choices made during the restoration. (Rest assured, if/when it’s published, I will write a review.)

Conclusion. Nothing I’ve said should prevent you from buying the new edition of Napoléon. Indeed, purely on the basis of supporting this film, its makers, its legacy, its restoration, and its overall cultural importance, I strongly urge you to buy it. Several years overdue, and goodness known how much overbudget, this is the longest version of the film we’re likely to see. The Cinémathèque française is not going to be funding any further work on Napoléon. Aside from anything else, the word “definitive” in all their marketing signals that they’re done with this film. The only question is whether you will be able to buy the Potemkine edition, and whether any alternate edition will be released on Blu-ray outside France. It would be a sad fate for this most cinematic of films to be limited to streaming via Netflix.

Paul Cuff