In 1923, budding director Clarence Brown signed a contract with Universal Pictures. After working on the courtroom drama The Acquittal (1923), he persuaded studio boss Cale Laemmle to fund a production set on a remote railway in the mountains. The film was to be an adaptation of a short story by Wadsworth Camp called “The Signal Tower”, published in the Metropolitan Magazine in 1920. Brown and his team headed to Mendocino County, California, where much of the film would be shot on location. The cameraman was Ben Reynolds, who had filmed all of Erich von Stroheim’s Universal films up to this point—and had recently finished shooting Greed (1924). Brown and Reynolds made the most of their setting, combining the mechanized world of the trains with the natural beauty of the mountain forests. Released in August 1924, The Signal Tower was acknowledged for its technical sophistication and boosted the profile of Brown—who would soon be called to work with bigger budgets and bigger stars.

The story is simple. David Taylor (Rockliffe Fellowes) lives in a remote house in the Mendocino Mountains with his wife Sally (Virginia Valli) and child Sonny (Frankie Darro). He works from midnight until noon in the railway signal tower at the base of the mountain, while his old coworker (and reliable lodger), “Uncle” Billy (James O. Barrows), operates the noon to midnight shift. When Billy is pensioned off to New York, his replacement is the caddish Joe Standish (Wallace Beery), who also becomes their new lodger. Cousin Gertie, who is staying with the Taylors, takes a shine to Joe—but Joe has eyes for Sally. At first David doesn’t believe that Joe has bad intentions, but when Joe makes a move on Sally he is ejected from the Taylor house. During a stormy night, Joe turns up drunk for his shift, so David must remain behind to try and derail the carriages before they smash into another train. Joe takes the opportunity to invade the Taylors’ home and try to assault Sally…

The Signal Tower may have a conventional narrative, but Brown gets the most he can out of the theme of a family under threat. What struck me throughout was the use made of location shooting. The first few minutes of the film consist of a lengthy series of shots showing the way the trains move through the mountainous, forested terrain. Regardless of one’s cultural interest in steam trains (Brown loved them, having an engineering background), the trains are nevertheless of dramatic importance in this sequence: they used to show the gradient of the land, the difficulty of passing from one section to the next, the nature of the track and how it is managed by the signal towers.

I have rhapsodized often enough about sunlight filtering through trees in silent films—but this is another beautiful example of how natural light, combined with deft composition and subtle tinting, produces a glorious vision of the remote forests. Brown related to Kevin Brownlow how he and Reynolds got up at 5 a.m. to photograph the first trains coming through the mountain forests with the sun rising behind them and filtering through the trees (The Parade’s Gone By…, 145). The effort was worth it.

See also how well the film integrates its titular setting into this landscape. After following the track and trains, we see the signal tower itself. We see outside it, inside it, through it. The glass windows surrounding the raised cabin offer a perfect integration of interior and exterior space. Brown took great lengths to get this set right, even fitting amber panes of glass to the tower when the exposure from natural sunlight was too much (ibid.).

The only other major interior setting in the film is the family home, just across from the signal tower. A title describes David’s home as the “terminal point” of his world. It’s a place of refuge. The interiors are a cosy den: the glowing hearth, the comfy chairs, the freshly-baked cakes.

But viewed from outside it feels very different. Brown shows us exteriors view of the house many times across the film. In some shots, the camera is closer to the bridge. We see David cross the stream at the end of his shift: it’s an image of comfort, of retreat. But look again: other shots are taken from further away. The camera lets the dark trees intrude on its view, emphasizing the isolated setting of this refuge, its vulnerability. And our perspective is influenced by the wording of the title that introduces us to David’s wife Sally. We read that she is “unconquered by the stagnant loneliness”. “Stagnant loneliness” is a fabulous phrase, one that hangs over what we see. It swiftly invites us to question David’s own mental image of home and work. Clearly, however well she copes, Sally is aware of the isolation of her home and the threat of external forces.

It is this tension between what characters see and what we see that characterizes much of the drama of The Signal Tower. The film is about a man whose duty it is to see danger, but who spends the first half of the film ignoring the warning signals from his own family. The film even makes David spell out the idea of duty taking precedence over everything else to his son. He tells Sonny that a signalman must know his line is clear before he can perform any other function. The seriousness of this idea is underlined by a flashback/fantasy sequence of a train crash (told with models); it’s quite a terrifying vision to impart to a child. But, of course, this warning David issues to his son about duty is the very conflict he himself faces at the end of the film. And though David is a reliable and dutiful man, he is also shown to be blind to other forms of danger. Immediately after the story of the signalman who forgot his orders, David once more goes to work. Look how Brown frames the family’s farewell: the group’s embrace is in the background, far enough away that it almost seems out of focus; while in the foreground, two dark branches threateningly cross the composition. It’s a curious, odd perspective—almost as though someone is watching them from the edge of the woods. There are threats lurking that David does not suspect.

If the rural isolation is sinister, the actual villain of the film turns out to be urbane. Wallace Beery’s Joe is an object of consternation for David when the former turns up for work in dapper suit, shoes, and hat. He looks totally alien to this environment.

His position within the family home, as the Taylors’ lodger, is likewise conspicuous—more so, since their last lodger was the elder Billy. Sally says Billy has “been like a father to us all”, and Billy himself has all the attributes of a loveable, rural oldster: the white hair, the little spectacles, the pipe, the stoop, the odd gait, the gentle smile. (He even gets the soft-focus treatment to make him look more huggable.) The film plays with how sinister Joe might be, since he is the subject of comic flirtation from Cousin Gertie when he first moves in. Joe’s magic tricks and fondness for Sonny offer a superficial air of innocence—but the way David keeps reassuring Sally that a man who likes children etc is “usually on the level” increases our suspicion (if not David’s).

The film offers us another external perspective when David and Sonny have a conversation with a passing engine driver, their friend Pete (J. Farrell MacDonald). Pete already knows Joe’s reputation and refers to him as “that railroad sheik”, the title italicizing the latter word for added emphasis. It’s another visual signal for us, the audience, to observe. We know by now that we shouldn’t trust Joe, but David seems oblivious to the warning signals. He blithely says that this “sheik” will be lonely now that Cousin Gertie is leaving. When Pete is about to ask David what this means for Sally, he is suddenly interrupted. A dribble of dark liquid falls over his forehead and face. It’s a strange, totally unexpected moment. Brown holds the close-up of Pete for several seconds and we’re left in the dark as to what’s going on. The sinister apparition of dark, sticky liquid could be a moment from a horror film—but what might be blood turns out to be engine oil, spilled by Sonny who’s playing in the engine. The shock becomes a moment of comedy, but it doesn’t quite diffuse sinister sense of threat that Brown creates with the image.

The scene is a kind of premonition, borne out by subsequent events. That very night, indeed, Joe makes his first move on Sally. And “move” is the right word, since Brown uses a tracking shot for the first time in any interior scene in the film. In a neat shot/reverse shot, the camera slowly recoils before Joe and creeps up upon Sally. It’s a threatening movement, and draws us uncomfortably closer—and closer—to Joe. His flirtations (especially with Gertie) have been mostly comic or ineffectual, but now the physical threat of his intentions is revealed. Beery can do bluff comedy, but the sheer bulk of the man makes him an imposing screen presence—especially when, as here, he fills the screen. His prim little moustache—like the stripes of his shirt or the gleam of his shoes—at first gave him an appearance of comic misplacement in this remote, rural environment. But now—as Joe looms in close-up—the moustache seems to emphasize his mouth, the curve of his lips, the broadness of his face as a whole.

These tracking shots presage the external danger of the last sequence. For this nighttime climax, Brown mounts the camera low down on the front of the engine: we hurtle though the dark landscape at breakneck speed. These tracking shots are exuberantly wild. We can hardly make out the terrain through which we plunge. Only the pale streaks of the tracks guide us through the gloom. It’s like all the menace of those slow tracks in the earlier scene with Sally/Joe are now fully unleashed. The external threat of the runaway train bearing down on David carries the horrible power that threatened—and, in the final scenes, threatens again—Sally and Sonny.

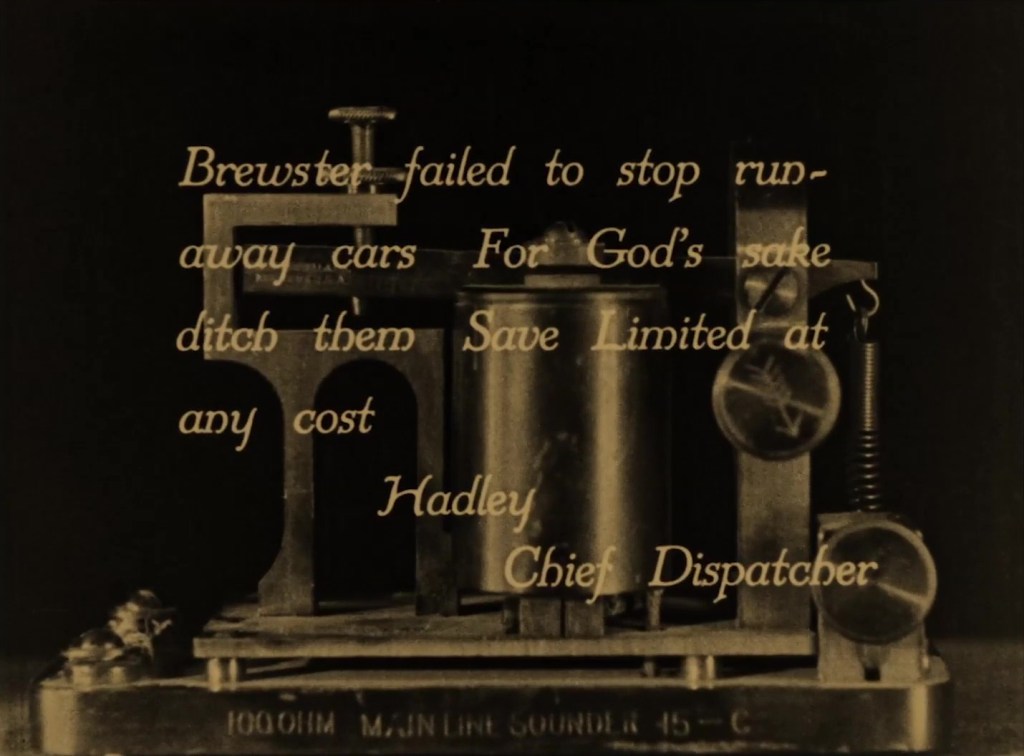

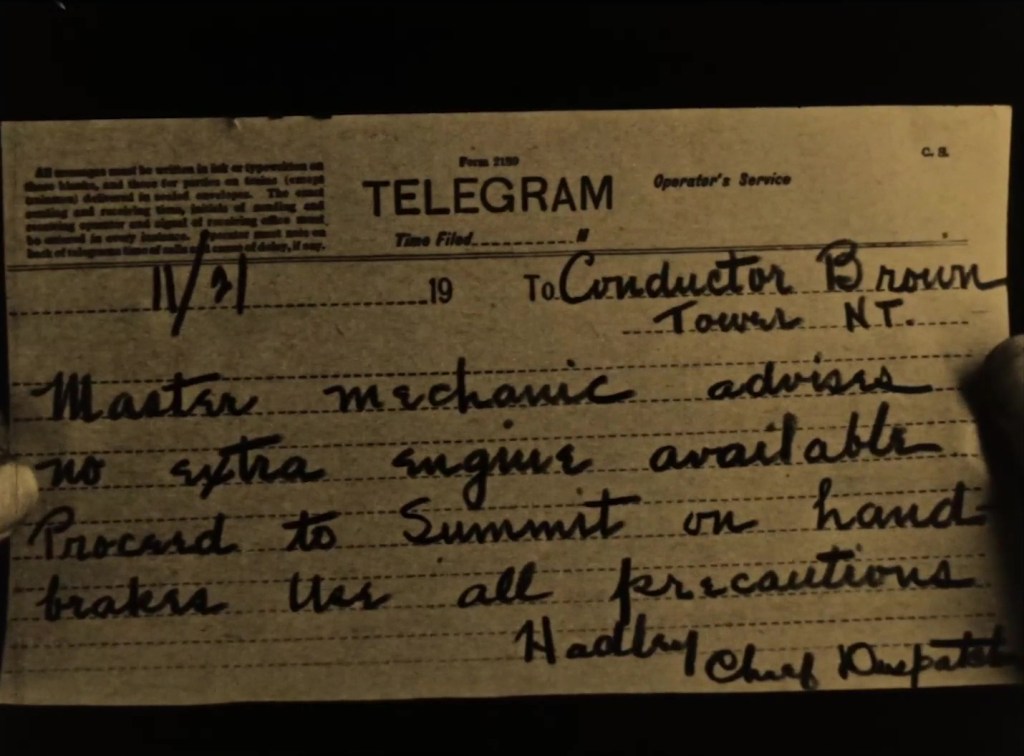

The intercutting of Joe’s attack on Sally and David’s desperate attempt to break the line and derail the runaway train is further complicated by the complex series of cutaway to different spaces. We see glimpses of telegrams from the various signallers, switchmen etc of the railway, together with the operatives themselves. You get some sense of the network of information going back and forth, as well the physical actions at ground level. Amid the skill of this sequence is a notable appearance on screen of Clarence Brown himself. We see him in the role of an anonymous signalman who tries (and fails) to stop the runaway train before it reaches David’s position. If there is irony in this first appearance (the film director as powerless agent), Brown’s second on-screen apparition is more subtle. For the author of one of the telegrams sent between the signallers at the end of the film is called “Conductor Brown”, a neat alternative name for director Brown. If David has been blind to the danger of Joe, here he takes care to receive instructions from the higher authority of conductor/director.

Indeed, it’s also noteworthy that David himself does not (cannot) come to the rescue of Sally herself. This is clearly the right moral decision (one life against the dozens or hundreds on the colliding trains) but presents the possibility of the price he must pay for duty. If “conductor Brown” appears in the telegram to issue clarification, the director Brown works to hide the climax of the struggle between Sally and Joe. This is revealed only later in flashback, so even when the runaway train is successfully derailed there is still tension hanging over David.

What saves Sally is actually the fact that Sonny ignored David’s instruction. David gave Sonny an unloaded gun to take back to the house, to make Sally feel reassured. But unbeknownst to him, Sonny also takes one bullet and loads the gun. What will save the day is also a foolhardy decision. There is a scene of comic tension when Sonny plays with the loaded gun, pointing it into his own face to look down the barrel. Thus, even the way the film finds to rescue Sally is through David’s blunder and Sonny’s near-disastrous recklessness.

When Sally arrives and relates how she shot Joe, the relief is subtly undermined in the way Brown frames the last shots of the family. Rather than the warm comfort of the home (which has itself been violated by Joe’s brutish assault through windows/doors), the family is reunited outside the signal tower, in the dark and the pouring rain. It’s a bracing kind of reunion, with father and mother and son being soaked in the cold. According to Gwenda Young, there was to have been another shot here:

Brown offers a final shot of the restorative embrace among husband, wife, and child, but he obscures our view by placing a hulking train in the foreground. It was a mark of Brown’s succinctness that he could encapsulate the film’s core theme of human (and familial) vulnerability in the face of the inescapable encroachment of modernity using just one shot. When Brown’s boss Carl Laemmle Sr. viewed the film, he was reportedly baffled by this scene, regarding it as a deliberate (and perverse) attempt to obscure, symbolically and visually, the ‘view’ of the restored family. Interestingly, his son Junior instantly understood what Brown was trying to achieve, and on his insistence, the shot was retained. (Clarence Brown, 44-45)

But I can’t see this shot in the 2019 restoration. Young derives her information from an interview Brown had with Brownlow in 1966, so perhaps this was a false memory—or this particular shot is missing from the current restoration.

What the surviving film does offer, however, is an even more threatening final image. Though we have seen the flashback to Sally shooting Joe, the film closes with an image of Joe escaping into the sodden forest. It’s a wonderfully expressive image, presenting a kind of vortex receding from foreground to background: the layers of tangled, sodden undergrowth and foliage lit by lightning or obscured in the dark. Successive layers of trees narrow our view: they form a kind of natural iris, leading the eye to the rear, where a circular gap in the leaves reveals Joe. The way he is framed here—his dark body against the dim blur of the clearing beyond—makes him the focus of the shot; but you realize that he’s looking at us, turning to give us a last glance. What really makes the shot is the way you can see Joe’s breath billowing out in the dark: it’s such a fantastic detail to include. It makes him a smouldering beast, retreating into the night. This final image is hardly comforting. The family is reunited, but the villain survives. Sally is saved from any guilt at having killed a man, but at the price of sending him out into the world once more. The family seem oblivious to Joe’s presence in the forest. Only we can see him, and he us. There’s an odd kind of complicity in this exchanged glance: we acknowledge Joe, just as Joe acknowledges us.

This 2019 restoration—from Photoplay Productions and the San Francisco Silent Film Festival—was based primarily on a 16mm print released in 1928 as part of Universal’s “Show-At-Home” series, with missing/damaged shots from another 16mm print of this same version. The restoration notes say that the film was originally 6207 feet, 6162 feet of which have been preserved in this version. The print looks very good, and I often forgot I was watching something from a 16mm source rather than 35mm. There are some scenes of inferior quality, but overall the texture of the image is very good, most especially for the exteriors.

The music for this restoration was written by Stephen Horne and performed by Horne and Martin Pyne. These two players swap between four instruments: the main part is for piano, with sections accompanied by drum kit, flute, or accordion. The main combination of instruments is piano and drum kit, which produces a marvellously evocative tone and timbre for the film. Listen to the opening sequence, the way the drums are about to evoke the texture and timbre of steam and mechanical movement, while the piano takes up the melodic line. The melodies are inflected with a slight ragtime lilt, which is a delight. Horne includes passages for flute (associated with Sally and the home), while Joe’s introduction gets accordion—a nice surprise, carrying a louche suggestiveness in its sliding wheeze. Altogether, a very effective accompaniment.

So there we are. The Signal Tower. A good film. And it’s certainly a more complex film than its story might suggest. Gwenda Young calls The Signal Tower “the first of Brown’s more personal films” (Clarence Brown, 45). Brown creates a rich sense of place, using and framing its locations in expressive ways. His careful compositions and camera movements make us question the assumptions of David. There are many deft touches that change our perspective on events and characters. But what it doesn’t offer is a wider perspective: there is little sense of the outside world this particular place. The Signal Tower uses its setting for drama, not social critique.

For example, David’s 12-hour shift sounds pretty brutal, but he never complains and seems to function perfectly well. Within the film, there is scant acknowledgement of how/when Dave or Sally (or Sonny) actually sleep. Sonny is put to bed once, and Sally spends one night(?) with him—but I was left curious as to how the 12-hour shift pattern works in a practical sense. The organizational hierarchy that demands its employees work like this is likewise never interrogated. Even when David’s long shift would potentially influence his behaviour/actions in the climactic scenes, the film doesn’t pick up on this. He is forced to work for more than twelve hours after Joe quits, but nothing is made of his (presumable) exhaustion as he battles the elements, the rails, and the spectre of Joe’s attack on Sally.

But if the film doesn’t offer a more complex social world, its concentration on the central drama makes it very effective.

Being familiar only with Brown’s later silent films (from The Eagle (1925) onwards), I am now very curious to see more of his work from this transitional period in the early/mid 1920s. In particular, I long to see a good quality version of Brown’s The Goose Woman (1925). I know that the film has been restored and shown in recent years, including with a piano score by Carl Davis. Here’s hoping that this and other neglected Clarence Brown films from the 1920s will get a proper release.

Paul Cuff

References

Kevin Brownlow, The Parade’s Gone By… (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1968).

Gwenda Young, Clarence Brown: Hollywood’s Forgotten Master (Kentucky UP, 2018).