On Day 7 of Bonn, we are once more treated to a full feature film presentation. For today, we are off to Denmark with that nation’s most popular comic duo of the silent era…

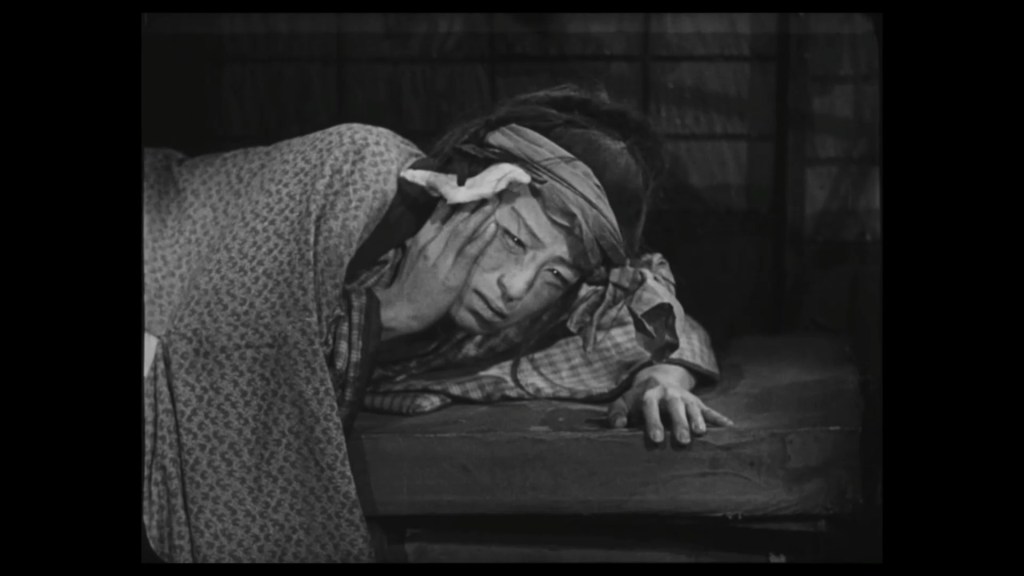

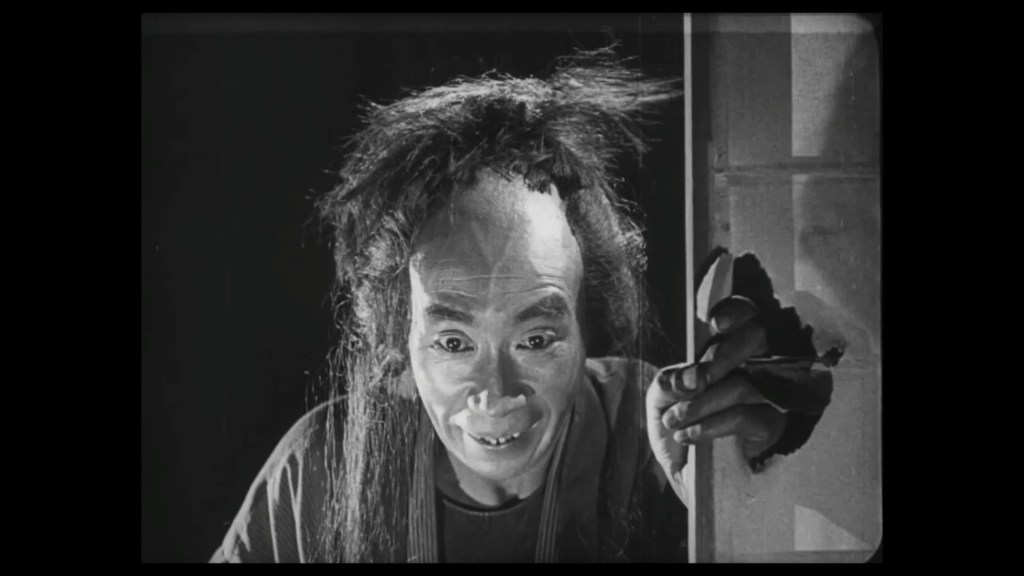

Krudt med Knald (1931; Den.; Lau Lauritzen Sr). Long and Short (Carl Schenstrøm and Harald Madsen) live in a boarding house, flirting with their young neighbours – a nimble duo of roller-skating dancers (Marguerite Viby, Nina Kalckar) – and making friends with their older neighbour, the Inventor (Jørgen Lund). The latter has invented a proto-televisual system, which is highly prized by a sinister trio of men representing “United Electric”. The trio move into the pension, aiming to steal the Inventor’s drawings and also the girls upstairs. After inadvertently foiling one attempt to steal the drawings, Long and Short are hired as drivers by the trio. Thinking this will get them out the way, the trio take the girls for a drive – but are once more stopped in their plans of seduction by Long and Short. Meanwhile, the Inventor signs a deal to gain half the profits from his invention from United Electric. But the trio from the company want to steal them from their boss to gain all the profits themselves. The trio enlist Long and Short to help them break into the office and the safe where the plans are, and arrange that the duo get arrested in their place. But the duo escape and save the day, catching the trio and saving the Inventor. ENDE

I’ll be honest: I feared that I wouldn’t get on with this film. I have been aware of the Danish comic duo Fyrtårnet and Bivognen for some years. Many of their films, including today’s, have been long available for free via the DFI silent film portal. But without subtitles or music, this little thread of silent film history has never enticed me to battle through. (On this same theme, I have had a deluxe Film Archiv Austria DVD edition of the films of early Austrian slapstick duo Cocl and Seff on my shelf for years. Somehow, I’ve never quite been in the mood to unwrap and investigate.) Yet this is precisely the kind of hesitancy I should overcome. After all, Danish silent cinema is a much more complex and multifaceted body of work than as represented by the canonical films of Benjamin Christiansen and Carl-Th. Dreyer, or the stardom of Asta Nielsen and Valdemar Psilander. The comic duo Fyrtårnet (Carl Schenstrøm) and Bivognen (Harald Madsen) were wildly popular in the 1920s and 1930s, and not just in Denmark. As the DFI page dedicated to their work reveals, under the names “Pat and Patachon” they were also big stars in Germany. Indeed, even the English version of the DFI pages on the duo stick with the Germanified “Pat and Patachon” as their non-Danish character names. “Long and Short” seem to be the English equivalent, and I only know this thanks to the English subtitles available on this presentation from Bonn.

All of which is to say that I was utterly unprepared for how much I enjoyed Krudt med Knald. I was also unprepared for the rhythm of the film, and how this heightened the pleasure of watching it. Though Long and Short (to reinstate their English aliases) are slapstick performers, the timing and execution of their gags do not attempt the speed or sheer breathtaking cleverness of Keaton, Lloyd, or Chaplin. They are a shambling, mostly slow-moving pair. One can follow their thought patterns more readily, watch their logic slowly unfold with everyday velocity. The opening scene is about neither character wanting to get up before the other: the Keaton-esque pulley system to tip one another out of bed is not especially sophisticated. (As compared to Keaton’s house in The Scarecrow (1920), for example.) But it’s character that seems to drive the gags, not the gags that define the character. It’s the mutual stubbornness, and the ultimately comradely and good-natured conclusion of the scene, that comes across – and brings the laughs.

The world they inhabit is also exceedingly well observed. The lengthy meal scene at their boarding house, overseen by the large landlady, is filled with brilliant touches. While the gags about increasingly large/tall/long-limbed neighbours at the table is good, if not necessarily sophisticated, the real laughs come from the manners and mores of the setting. The film cuts from the duo’s resigned efforts to make the most of their miserly portions to wall-mounted slogans about the health benefits of privation: “Keep sound: Don’t eat too much.” “To eat one’s fill is to eat too much.” “The less you eat, the better you feel.” The efforts of Long and Short to fit in (literally and metaphorically) to the pretensions of their petit-bourgeois hostess is marvellous.

Later, there is another rather shambling sequence involving a sleepwalking Short, who walks along the rooftop of the boarding house and frightens the inhabitants. A rooftop sleepwalking sequence is hardly novel (especially for 1931), and it doesn’t pretend to offer the suspense or drama of the stunt work of a Keaton or Lloyd. But what it does instead is take the opportunity to poke fun at the landlady and her friends, who are busy having a séance. When the landlady sees the silhouette of Short, wrapped in his bedsheet, she screams: “It was Napoleon!” It’s a brilliant gag, in which the landlady’s fear also boasts of her pretension at having summoned a mighty name of history to her boarding house séance. The payoff, too, is surprising. For Short’s friends all rally round him and they form a little community, gathered round the Inventor in mutual support.

Time and again, I was surprised by how plot lines or details of character developed in unexpected directions. For example, the Inventor is portrayed initially as a comic figure, inspired by drink. “At the bottom: that’s where the good ideas are!”, the Inventor explains to Long and Short, motioning to his bottle of liqueur. “I’ve never found anything up there”, he adds, pointing to the top of the bottle. It’s a marvellous line. (And the kind of joke about drink and human foibles that still inflects Danish cinema today.) But it also marks the old man as vulnerable and human, facets which foster his friendship with Long and Short, and with the two performing girls.

Regarding the latter, I was also very touched at how Long and Short treat them with almost chaste respect. There is no romance as such, just a kind of comradely innocence and mutual respect. The pleasure of their relationship is not so much the prospect of romantic love as of protective friendship. We first meet the girls on the rooftop of the boarding house, where they are trying out their new “number” on roller-skates. It’s an entirely unnecessary sequence, as far as narrative is concerned, but it’s utterly, utterly delightful. Filmed on an actual rooftop overlooking the city (Copenhagen, one assumes – but I’ll gladly be corrected), there is a real sense of freedom and space – but a freedom and space that are also limited. It’s a moment of joy, demarcated in this small, somewhat precarious space, but set against the bright, open sky and the huge sweep of the cityscape. It’s more than charming or silly, it’s really rather beautiful.

Indeed, there are many moments like this, when the use of location is more than merely incidental but striking and beautiful. The yard where Long and Short are employed to move barrels has some amazing piles of materiel, used to striking effect in some compositions (as when the dup appear right on top of a mountain of barrels) – and for an extended and wonderful sequence involving hiding from the police among the barrels. Here again, it’s not so much the speed of the chase as the sheer extension of the gag: Long and Short popping up and down at random places amid the barrels, while an ever-increasing number of policemen crawl into the maze.

Later, there are also some gorgeous glimpses of the summer landscape. There is a shot of the duo driving through a wheat field in which we see only their heads and shoulders moving through the crop. The sky is bright, the wheat is swaying in the breeze. It’s a surreal sight, wonderfully shot and composed. But there is also great beauty in the way the scene shows us the sweep of countryside. The scene lingers just long enough for the sway of the crop and the treetops to become a subject of contemplation. Even in the middle of a chase sequence, the film is paced and short such as to have an interest that is more than merely narrative.

Krudt med Knald is also weirdly moving. I’ve tried to explain above how the rhythm of the film allows for an accrued sense of emotional engagement – at least with this viewer. So when we see the Inventor, the duo, and the girls join forces and make friends in the boarding house – not just sticking together but living together in one toom – I was genuinely glad that these people – poor, struggling, disappointed, but hopeful – came together. Whenever there is misfortune to any of them, they come together to commiserate or reassure. When Long and Short finally earn some money, the first thing they do is buy food and drink to share with their friends.

That the film successfully mobilizes a sense of emotional connection is really felt near the end. When, near the end, Long and Short have been supposedly caught in the act of stealing the Inventor’s plans to give to the criminal trio, all their friends are present to witness their arrest by the police. The moment when the girls and the Inventor believe that the duo have betrayed them packs far more emotional punch than I expected. It’s not the outrage at false accusation that stings so much as the hurt of betrayal by those they believed were their friends. It’s very subtly played. (One can imagine a Hollywood production laying it on more thickly.) And it’s the subtleness that gives it an emotional reality, an emotional edge. So it’s all the more effective when we see the group all together in the final scene, where a dinner has been arranged to celebrate the Inventor’s success with United Electric. “This is one of the happiest days of my life!”, the Inventor says. “And I am fill of the deepest gratitude… especially towards my two friends…” – and here his hand falls for a moment on Long’s shoulder. His words, and the performances here, make this moment surprisingly touching. Isn’t it nice to feel happy for such characters? It isn’t the neatness of the narrative resolution, it’s the cumulative sense of comradery build up between character, and between them and us, that makes the end effective.

I should also mention that the film’s title Krudt med Knald seems literally to translate as “Gunpowder with a bang”, but is translated in this presentation as “Long and Short invent Gunpowder”. Original and given titles are both somewhat misleading, but this seems to me rather typical of the film’s approach. One subplot is indeed about Short trying to concoct his own brand of gunpowder. He is inspired by the Inventor’s reliance on alcohol to fuel his inventiveness, so starts guzzling bottles to receive inspiration. It’s a silly plotline, one that interacts only tangentially with the main storyline of the Inventor and his drawings. But it is the source of some good gags, especially the postscript to the final dinner scene. Here, Short is ready to show off his own invention to the assembled cast. As he prepares his experiment, the film cuts back and forth from Short’s preparations (the danger of which looks increasingly alarming) to the guests leaving, one-by-one. The time this gag takes to unfold is typical of the film’s rhythm: it’s quite slow, but the sheer elaboration of the single gag attains its own humour. The pay-off is exactly as one would expect: there is a huge explosion, with Long and Short emerging, smoke-blackened and in tatters, from the wreckage of the room. But the pleasure is not in being surprised, so much as in seeing the inevitable conclusion of this plotline, so long prepared and so inevitable that the sheer pointlessness of it – and its stubborn and unnecessary pursuit – is itself the source of humour. By this point, I had already been totally won over by the film. The cumulative silliness had me chuckling throughout Short’s demonstration. And the final shot, of both characters looking directly at the camera, is both funny and touching. Their look is not one of pleading or bafflement or attention-seeking, but a pleasing moment of engagement from character to spectator. And the way Long strokes away the ash from Short’s head – an act of cleanliness, yes, but more a gesture of care and affection – sums up the curious emotional tenor of the film. It’s deadline and funny and moving all at once. A lovely way to end.

The presentation of Krudt med Knald via the DFI portal is with replacement (i.e. modern, digital) intertitles in Danish. There is neither music for subtitle options, so while looking great the video is useful only to the more devotedly interested. As presented here at Bonn, the film has new digital German titles (a sensible option, given that no original aesthetic is being lost) and optional English subtitles. There is also a pleasing musical accompaniment for electric guitar and piano by Tobias Stutz and Felix Ohlert. Like the film, the music has an amiable, rambling quality that suits what I might call the gentleness of the film. While I am curious about the kind of musical accompaniment available in 1931, it was nice to see the film with music that didn’t overstate itself. It’s a curiously subtle film, one that might easily be overpowered by too strident a score.

So, overall, a very pleasant experience. I’m so glad that I’ve finally seen something with Fyrtårnet and Bivognen, as they have been on my horizon for years. While their films have been available via the DFI, this is the first time I’ve had the chance to see one presented in such a way that I gladly seized the chance to sit down and watch it. (As a foot note to the pertinence of programming this film, it was a pleasure to see the Danish director Holger-Madsen playing the small role of the detective. Given that we saw one of his films on Day 4 of Bonn this year, and that I have recently been trying to track down a copy of one of his German films of late, it was rather nice to see the man himself, alive and well and very much not lost from history.)

In sum, Krudt med Knald was a delightful surprise. But that’s rather what I’ve come to expect from the programme at Bonn.

Paul Cuff