I’ve just returned from a rather intense and wonderful few days in Berlin, gorging on culture of all kinds. (And on some seasonal German dishes, too.) I would be settling down to write about the filmic aspects of this trip, were it not for the fact that by the time I landed the Pordenone festival had already begun. Pausing only to shower, receive a flu vaccination, make some rice, upload a thousand photographs, and take the car for its MOT, I logged in to my streaming account and fell headlong into Day 1…

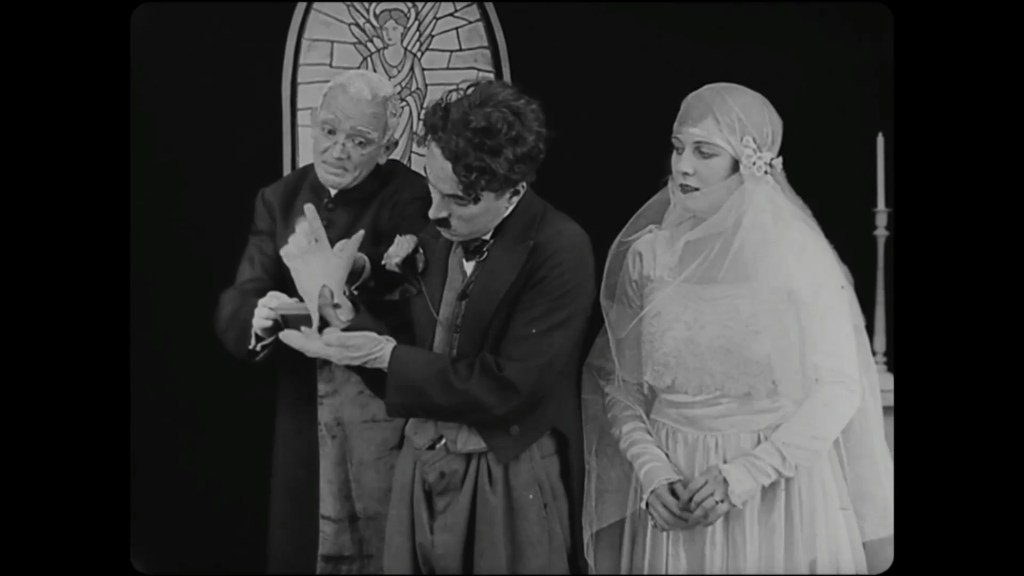

The Bond (1918; US; Charlie Chaplin). Famous for its final scene of the Tramp biffing Kaiser Wilhelm over the head with a large mallet, this short film begins with a rather more subtle and sophisticated series of sketches exploring other “bonds”. “The bond of friendship”, “The bond of love”, and “The marriage bond” are delightful vignettes, set against beautifully simple, picture-book style backgrounds (entirely black, with two-dimensional details that sometimes take on unexpected depth). Chaplin undercuts the premise of the first (getting increasingly fed-up by his friend’s friendliness), makes the second surreally literal (he is shot by Cupid’s arrow, then gets tied up with the object of his love), and undercuts the third (he resents paying the priest and gets hit with the lucky shoe). The final sketch, “The liberty bond”, is a rather brilliant series of diagrammatic tableaux in which Chaplin illustrates the motive, method, and outcome of wartime liberty bonds. He manages to be both sincere, charming, and funny – a very difficult combination to bring off in what is essentially state propaganda (albeit for a good cause). Chaplin makes human what could easily be stilted or polemic.

His Day Out (1918; US; Arvid E. Gillstrom). Our second short from 1918, this time not with Chaplin but with Chaplin’s most persistent and successful impersonator: Billy West. The film is a rather disjointed series of skits, the best of which is the prolonged scene in the barbershop in which Chaplin West variously shaves/assaults/preens/insults/scams his customers – including Oliver Hardy. (Inevitably, they all reappear in the slapstick finale.) It’s all very silly, but there is something inherently strange about watching this uncanny Chaplin. And as funny as some moments are, the film inevitably suffers from evidently not being by Chaplin. West is less sharp in every facet: less elegant, less quick, less touching than Chaplin. The very fact of his trying to be someone else (and not even this: he is being someone else’s persona, performing someone else’s performance) robs something of the pleasure in watching the film. Nevertheless, an interesting curiosity.

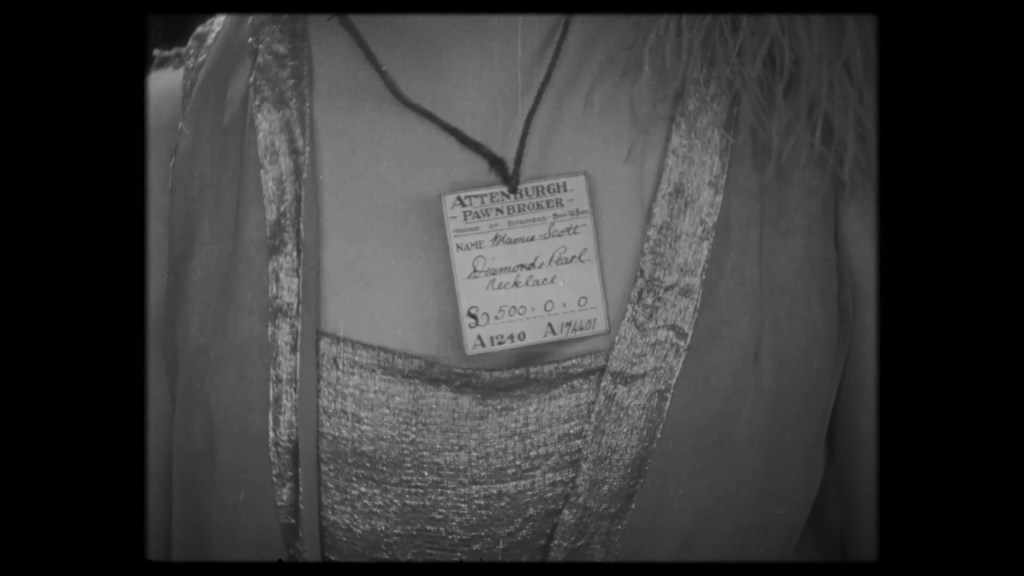

A Little Bit of Fluff (1928; UK; Jess Robbins/Wheeler Dryden). Our main feature presentation follows newlyweds Bertram Tully (Syd Chaplin) and Violet (Nancy Rigg), who live under the thumb of Violet’s imposing mother. While she and Violet are away visiting an aunt, Betram encounters the woman next door: the dancer Mamie Scott (Betty Balfour). Mamie and mutual friend John invite Bertram to the Five Hundred Club, where Betram accidentally gets hold of Mamie’s valuable necklace. There ensues a series of farcical encounters, mistaken identities, and run-ins with jealous boyfriends, the police, and criminals in disguise…

This film was an absolute unknown for me, so I was very pleased at how charming and funny it was. Sydney Chaplin is known to me (as I imagine to most) for his later role as his half-brother Charlie’s off-screen assistant, so seeing him take centre stage was fascinating to watch. He is delightful as the fey, trod-upon, Betram – a character whose name evokes Bertie Wooster, just as his actions undergo a very Woodhousian series of mistakes and minor disasters. (Troublesome matriarchs, nightclub misdemeanours, adventurous dancers, valuable necklaces, fake burglaries, and jealous boyfriends are all Woodhouse tropes, as they must have been for any number of stage comedies of the 1920s.) Syd Chaplin makes the most of his character’s small world and narrowed expectations. I love that his only visible pleasure is to play the flute, and even this is somehow a struggle and an imposition. (When he plays, he keeps blowing out his candle.)

Indeed, everything Bertram does goes wrong. The meekness of his character means that the increasing difficulty of his situation brings out wonderful and unexpected bursts of face-saving improvisation and expressive energy. I found myself laughing a great deal when Betram is cornered and has to find a desperate way out. The scene in which he his trapped between police, Mamie’s thuggish ex, and the police outside, is a delight. Ultimately forced into Mamie’s bathroom while she is bathing, and having first to impersonate her maid and then to impersonate Mamie herself, Bertram finds – just – a way out of his predicament, while also finding delight in his own ingenuity. The way he dons Mamie’s gown and bonnet, then sets out polishing his nails and smothering himself in powder, he seems to get lost in the pleasure of being someone else: having so often fallen short in fulfilling his masculine role, here is finds refuge in an exaggerated femininity.

I also loved the scene in which, trying to get his friend to back-up his alibi, he desperately mimes the title of the play and author they have supposedly seen. His mime, first “Love’s Labour Lost”, then of “Shakespeare”, is brilliant: it’s funny because it’s both an accurate mime, inaccurately identified (John announces that they saw “Gold Diggers” by Bernard Shaw), but because it once again gets this meek character to perform outlandish gestures. Having been discovered in women’s clothing by his mother-in-law, he is now discovered waving a speer by his wife. The shock of these disruptions to his usual character, and his own evident delight at his ability to perform as (respectively) highly feminine and masculine personae, make for wonderful sequences. They are also a marker of Chaplin’s ability to win us over to his character, making us believe both his meekness and his untapped performance abilities. The way each scene seems to snowball through a series of small incidents into absurd situations is both a dramatic success, but also a way for Chaplin to demonstrate a range of performance style – from small details to broad slapstick. But the film doesn’t offer any great transformation of Bertram’s character, and I rather liked how there is no effort to make us believe he has quite learned anything about himself, or that he has – ultimately – improved his lot. Early in the film, he sees the newspaper headline: “Man chokes mother-in-law”, and it’s clearly an unconscious fantasy. Even if the film has shown that he has untapped energies, he never (in the manner of a Keaton or Lloyd feature film) proves himself. There is no defeat or exile of the mother-in-law, just as Bertram himself never foils the real burglar to save the day. His successes are accidents, and at the end of the film he sinks into unconsciousness, oblivious as to what he may – or may not – have done.

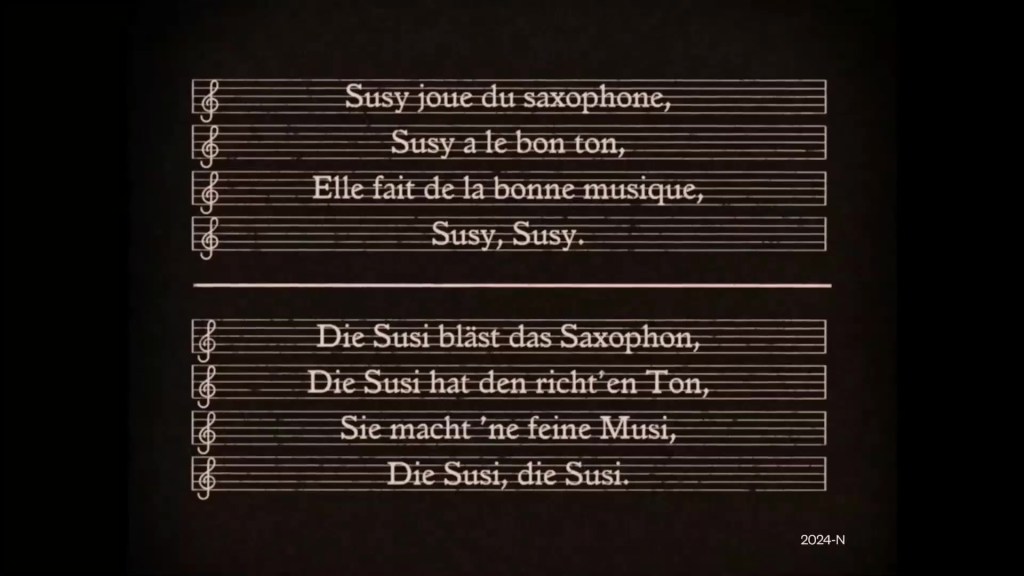

I must also mention Betty Balfour. Balfour was a major star of British cinema, maintaining her popularity with audiences throughout the 1920s. She starred in a number of foreign films as well, but I’m not sure her fame ever really had much impact beyond the UK. Even if her eponymous character is as superficial as the titular A Bit of Fluff suggests, Balfour holds her own on screen here: she’s happy to sing and dance and get involved in slapstick and farce. Balfour’s character is introduced as “celebrating the tenth anniversary of her 25th birthday”, but the film never makes her a villainous figure. (It’s worth noting that Balfour was only just older than 25 when she made this film.) She’s strong-willed and independent, traits which are never condemned. She also gets some nice lines of dialogue, as when Henry asks to borrow her necklace, to which she replies: “You showed my ring to a friend and she’s still looking at it.” Here, as often in the film, a single line of dialogue tells you much about the character and her relationship and past with others.

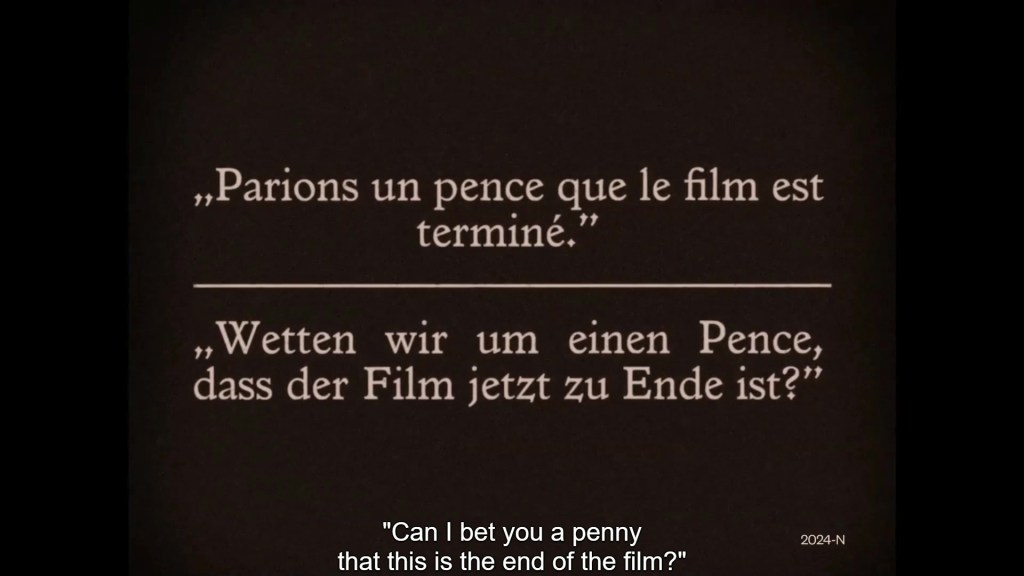

So that was Day 1 of Pordenone from afar. Having barely had a chance to stand still for a few minutes since I returned to the UK, I ignored all context for this Day 1 programme and ploughed straight through the content. Emerging from this rather mad dash and finding time to pause of think, I realize what a delightful programme this was, themed around various Chaplins: Charlie Chaplin, fake Charlie Chaplin, and Sydney Chaplin. It makes for a wonderful journey through the silent era, from the short slapstick of the late 1910s to the more elaborate narrative feature comedy of the late 1920s, from the most famous Chaplin who ever lived to the Chaplin who is more famous as an off-screen assistant than an on-screen lead. Starting with the familiar, moving to the familiar-yet-unfamiliar, and concluding with the hardly known is a superb way of guiding us through these three films and their stars. I hadn’t seen The Bond for many years, and it was a huge pleasure to be reminded of the context for that famous image of Chaplin with his foot on the vanquished Kaiser. (Having just returned from Berlin, I have been seeing much imagery from Wilhelmine Germany.) I had never seen either of the other films, and these are just the kind of thing I hope to encounter at a festival. If Billy West offered a rather uncanny experience, profoundly overshadowed by the real Charlie Chaplin, then Syd Chaplin was absolutely his own man. I had a great time watching A Little Bit of Fluff and was charmed by Syd’s genteelly hapless character. It was also a pleasure to see Betty Balfour, a star whose historical popularity stands in marked contrast to the difficulty of seeing her films nowadays. There are also nice echoes to Charlie Chaplin’s work in the other films: from the extendable barber chair in His Day Out (reminiscent of The Great Dictator (1940)) to the gag when Bertram uses his hands to make some dolls dance (reminiscent of the famous dance of the rolls/forks gag in The Gold Rush (1925)). It really is a superb trio of films that rhyme and contrast in pleasing ways. All in all, a highly engaging evening at the pictures. (Well… a highly engaging couple of hours in front of my television screen, anyway.) The piano music for the comic shorts (by Meg Morley) and for the main feature (by Donald Sosin) was, of course, exemplary. A marvellous start to this year’s festival.

Paul Cuff