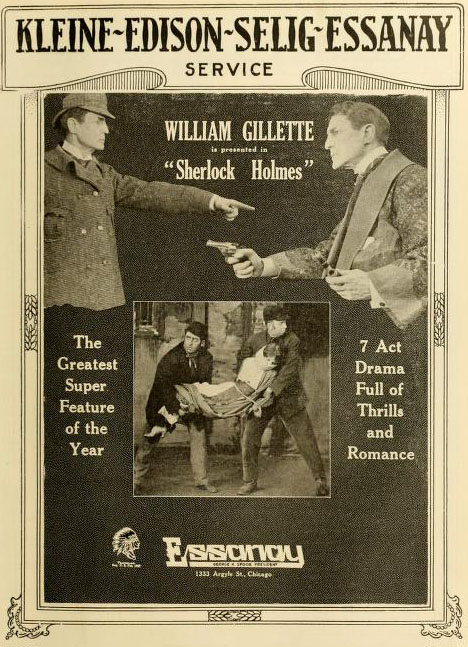

Conan Doyle killed off Sherlock Holmes in 1893. But although he professed no interest in writing more stories about his famous character, he didn’t mind making more money from him. A play based on Holmes was mooted, planned, then put off. It was then taken up by the American actor and dramatist William Gillette. Seeking to make the stories more appealing to audiences, Gillette took plenty of liberties with the source material. Concerned over the denouement he was planning, he cabled Conan Doyle and asked: “May I marry Holmes?” Conan Doyle replied: “You may marry him, murder him, or do anything you like to him.” So Gillette did. His play Sherlock Holmes (1899) was ludicrously successful, and Gillette had played Holmes over 1,300 times by the time a film version of the play was produced by Essanay Studios in 1916. Long considered lost, the film was rediscovered nearly a hundred years after it was made. It offers the unique opportunity to see the early twentieth century’s most successful Holmes…

Sherlock Holmes (1916; US; Arthur Berthelet)

“This film is an exact reproduction of the play that has been performed to great acclaim for the past five years throughout America and England. The actors in the film are the same ones from the play.” So says the opening title. For whatever reason (did they count only the most recent run of performances?), the play in its various guises had been running for 17 years by 1916. Perhaps saying “This play has been running for 17 years” would make it sound rather passé?

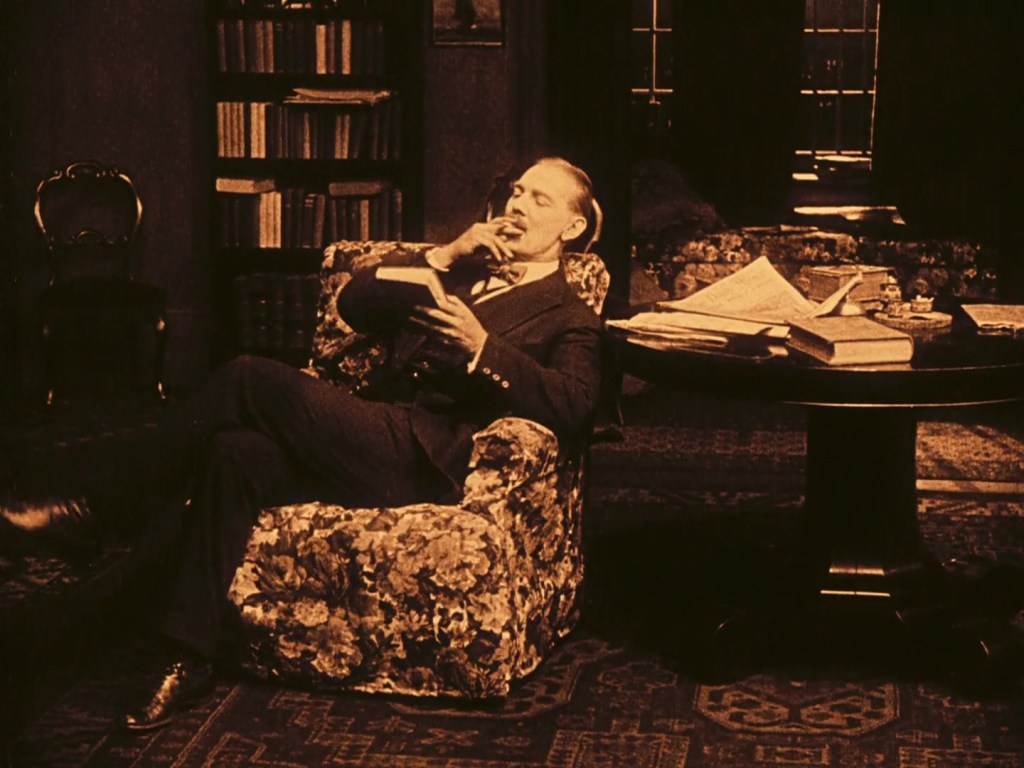

Here is William Gillette as Holmes. He’s given his own introduction on screen. Holmes is in his den, surrounded by scientific equipment. He’s even wearing a full lab coat. A phrenological skull sits on a ledge. It’s a great image, and Gillette looks every inch the character: the face, the posture, the build.

And now for the plot. Oh dear. Well, it’s a chunk of “A Scandal in Bohemia”, rendered more respectable. Instead of Irene Adler bearing the letters written to her personally by a prince, the equivalent character is killed off before we even start the film. Her innocent sister Alice Faulkner possesses them, but is pursued by the prince’s agents (again, the writer of anything “indiscreet” is pushed out of sight). But it’s the Larrabees and their compatriot Sid who muscle in on the act to capture Alice and her letters first. Cue endless opening and shutting of doors, listening through keyholes, standing up and professing innocence, opening and shutting more doors, clasping hands, putting on and taking off coats.

But here’s Holmes again, in Baker Street. We aren’t shown the outside of his quarters, yet; indeed, this film tries not to show us too much of the world outside at all: for Chicago is clearly not London. The apartment is small, simple; there’s a small table, a comfy chair, a fireplace. But who else is around? Mrs Hudson? No. Watson? No. But Billy’s here! Yup, Billy. You remember Billy, right? (Uh, no.) Well, here he seems to be a servant. He ushers in… Watson! Finally, here’s Watson. In the role, Edward Fielding looks as Watsony as one might wish: good-natured, smart, moustached. He goes upstairs. Holmes welcomes him, shows him the plan of the Larrabee house he’s about to enter. They talk. Holmes dresses. Watson stays behind. “Let me recommend these books while you wait for me”, says Holmes. And in one of the most dramatically pointless scenes in the film, he looks for a book, finds one, lights a cigarette, and sits to read.

Cut to the Larrabees, trying to find the letters. Sid turns up. More walking into rooms, looking through secret windows. While they scheme, their servant Forman watches. Forman is an agent of Holmes. More intrigue. Upstairs, Alice is locked in her room. Another ancillary character, the French maid Thérèse (why French?) “feels sympathetic toward unfortunate Alice”. So she lets Alice out of her room. Alice comes down. More professions of innocent outrage.

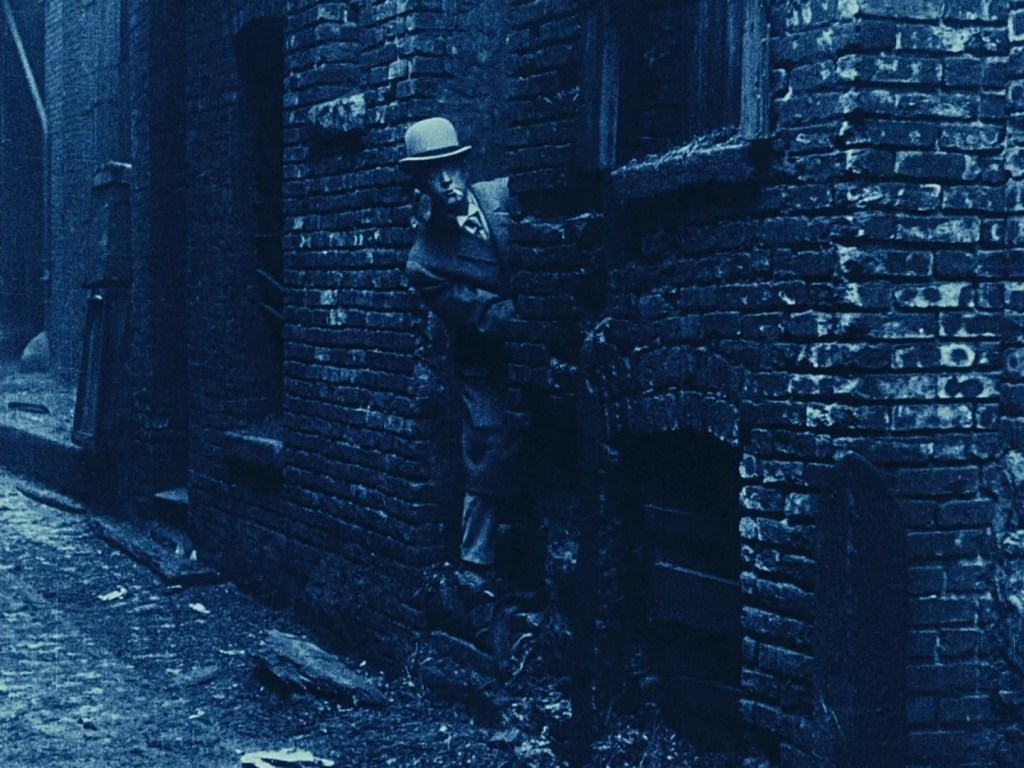

But here’s Holmes! Look at the way he holds himself as he comes to inspect the exterior of the house. Gillette is tall, upright, domineering. Look at the way he holds his cane. The character has a past in this body, in these gestures. It’s a pleasure to see him just stand there, making himself prominent. He also spends most of this film in impeccable clothes. Almost too impeccable. No wonder he needs a servant in Baker Street to help dress him.

When Holmes appears at the door, one of the gang describes him as “A tall, thin man… about forty, with a smooth face… wearing a long coat and carrying an ebony cane.” The description is almost accurate (Gillette was already in his sixties by this time); but why are we bothering to read it? We’ve just seen what she sees, after all. This first part of the film wastes a lot of time. The gang now spend forever working out what to do. People open and shut doors, whisper, wring hands.

Forman lets Holmes in (a full two minutes after he has rung the doorbell). Holmes comes in. When the others are out, he examines the room. The camera tracks from right to left to follow him, then dissolves to a medium shot as he examines door, piano, safe. It’s about the only scene in the film where the camera moves: it’s quite a nice move, allowing Gillette’s performance the space to unfold, to (quite literally) track his movements across the scene. But the film has scant close-ups, either of faces or (more significant in a detective drama) of details (clues!). Holmes confers with Forman, while upstairs one of the Larrabbees dresses as Alice to try and fob him off. The scene drags on so long there’s a reel-change halfway through, as Holmes waits for something to happen. Holmes gets Forman to start a fire and thus reveal where Alice has hidden the letters. But he is so moved by her tearful reaction that he lets her keep the letters. (Gillette plays this emotion very subtly, with a simple downward dip of the head.) Holmes leaves, having neither rescued the girl nor the letters. There’s yet another pointless scene of Sid being caught trying to nab the letters as Holmes leaves. We’re 38 minutes into the film, and essentially nothing has happened. All the characters are where they started, with little having been achieved.

Pity poor Watson, who’s still reading a book. He leaves, as he “really can’t wait any longer”. (I know the feeling, doctor.) The Larrabees say they will contact Moriarty, “the Emperor of crime”, to help them.

Holmes returns to Baker Street. Billy helps him disrobe and put on a spectacular smoking jacket. He lights a pipe and reflects. Alice, meanwhile, is reflecting too. A superimposed vision of Holmes appears. She goes goofy, dreamy. He, too, “starts to dream” back in Baker Street: “Through the blue haze, he sees the sweet figure of Alice Faulkner.” Oh dear, oh dear.

Now to Moriarty (Ernest Maupain), in his underground lair. It’s a chiaroscuro scene, dark apart from a few patches of light, the faces of Moriarty and his henchman. Moriarty keeps “a small burner” built into his desk, “to keep his papers safe from prying eyes”. It’s an absurd device, which characters have to make great effort to lean into to pretend it’s effective. Its real function is an excuse for Moriarty to be lit from below and appear more sinister. Moriarty tells them to get rid of Forman and that he will deal with Holmes.

So Forman is set upon, but the French maid sees this and rushes to tell Holmes. But here is Forman, who is still not dead. But he’s immediately set upon—again!—when he goes outside, as Moriarty makes his way over. This encounter (much revisited in later adaptations) eventually turns into a crude, tedious melodrama as a fight between Billy and Moriarty’s sidekick goes on downstairs, and the professor quizzes Holmes upstairs—then tries and fails to wield a gun. Even the slow dissolves to details—Moriarty pausing to take off his scarf, Billy later confiscating his gun—are weirdly portentous without real purpose. Moriarty tries to shoot Holmes yet again, but Holmes has arranged for the bullets to be removed. Yet again a great deal of coming and going has happened for little purpose.

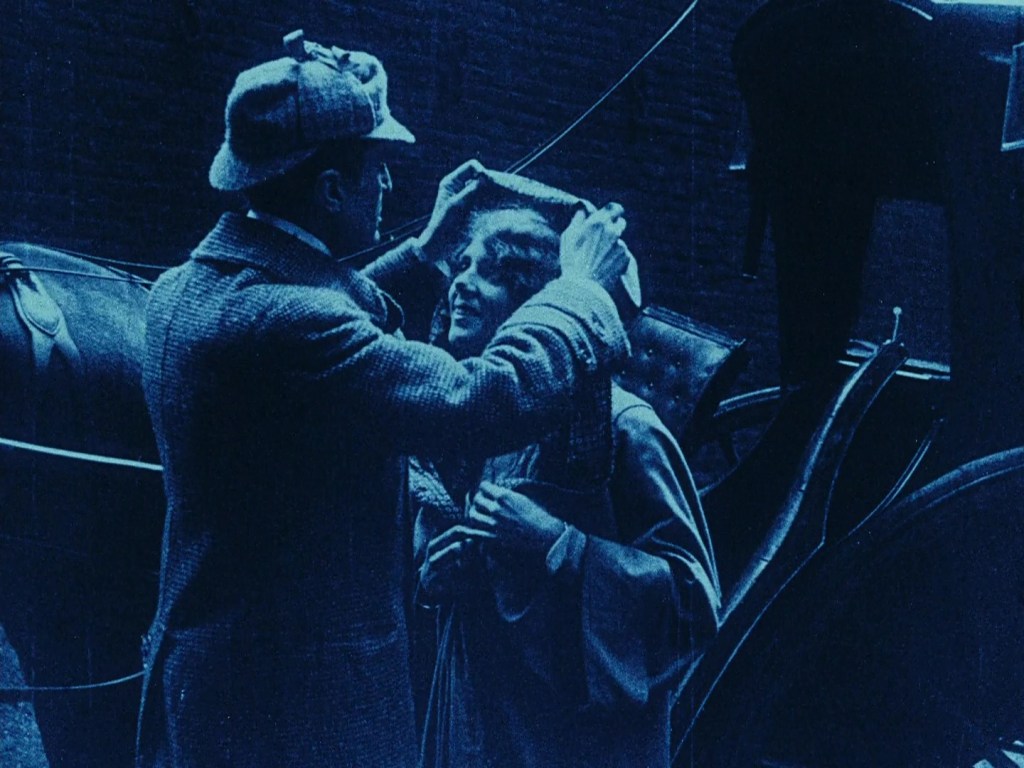

Next comes a famous sequence from the stage play: the escape from the Stepney Gas Chamber. All the criminals show up, shadowed by Alice (wasn’t she supposed to be imprisoned in the Larrabees’ house?). Yet another unnecessarily longwinded series of people coming and going. A whole gang, including Moriarty are crammed into the scene. Everything is gone over time and again, which makes their plan’s failure when Holmes turns up all the more absurd. It all takes so long: Holmes wanders around; Larrabee smokes; Holmes wanders around; then they don’t speak. Larrabee is literally tapping his fingers with boredom on his leg. Holmes finds Alice tied up (but apparently unguarded) and is then ineffectually set upon by some roughs: rather, just one rough, as the others prefer to stand back and gurn sinisterly rather than help. Next comes something that I imagine worked very well in the theatre: the lights go out, leaving only Holmes’ glowing cigar end to guide the thugs. But the cigar is perched on a ledge, and Holmes is already outside. Holmes sends Alice off in a cab, then gets the police to arrest the gang. (He himself stays outside to look smug—but Moriarty has escaped.)

Now for a scene with Watson in his office. “221B Baker Street had been set on fire, so Holmes has been seeing his clients in Dr Watson’s office.” That the film makes no effort to explain this event, let alone show it, is baffling. Baffling too is when Sid turns up to make a signal at the window. Why? All that happens (eventually) is that one of the Larrabees turns up. Did that really need all Sid’s antics to set up? But here is Holmes in disguise (the camera dissolves to a closer view to admire his ridiculous false nose). More coming and going. The Larrabee again signals at the window, but why is still not clear. Moriarty is disguising himself as a cab driver (with a ridiculous moustache and eye patch), but Billy has spied this and lets Holmes know. With the aid of Forman (who is apparently still not dead), Moriarty is caught and led away.

Watson and Holmes talk. Holmes sets up yet another elaborate scheme for being overheard, this time by Alice. Watson smiles. “You’re in love!” he says. Gillette makes this utterly un-Holmesian scene touching: he reaches out and clasps Watson’s pocket, nodding. He plays it so subtly—his eyebrows tensing, his mouth pursing a little—that you almost forget what a garble is the surrounding drama. So there’s more coming and going with the prince’s agents, and Alice eventually enters and gives Holmes the letters—which he then gives back to her, and she gives them back to the agents. Holmes reveals that it’s all been a trick to get her to do this. He says he will “say goodbye and leave forever”. But she asks him to stay, for “we still have many things to say to each other”. They go to the fireplace. “And Holmes stayed”, states an intertitle. THE END.

Lord, what a mess of a drama. It’s what Watson (if he’d been given a proper scene) would have called “ineffable twaddle”. Endlessly elaborate set-ups, endless minor characters, endless comings and goings—all for the inanest of results. I still can’t believe Watson spends the first TWO REELS of this film sat in a chair, reading, waiting for Holmes to speak to him. It’s symptomatic of how many early Holmes adaptations side-line Watson’s character. The Anglo-French series made by the Éclair Company (eight films, 1912-13), for example, or the German series Der Hund von Baskerville (six films, 1914-20), each do without Watson altogether. Gillette’s 1916 film at least includes Watson, but he serves no dramatic purpose whatsoever. The tiny moment when Holmes reaches out to Watson near the end of the film: that’s the only moment of genuine friendship, of believable feeling, in the entire film. I know I’m writing from a point of view in time when the Holmes-Watson relationship has been the mainstay of most adaptations from the Basil Rathbone/Nigel Bruce films onwards, but even so—this 1916 version is so contrived, so filled with uninteresting minor characters, that it misses the chance to develop the one genuine relationship it has on screen.

But for all its ludicrous clunkiness as drama, this film does have one great facet: William Gillette really is a superb Holmes. His cool, reserved performance is marvellously subtle and understated. It’s a reminder that such performers and performances could and did exist at the dawn of the twentieth century. When the word “theatrical” is used to describe early film performances, it’s usually a criticism. Here is a performance honed 1,300 times on stage since 1899, and it’s the most naturalistic, convincing thing in the film. It’s fantastic to see all the trademarks of later Holmeses here: the smoking jacket, the pipe, the deerstalker, the magnifying glass. Even if they serve a stupid plot (or have nothing to do with it), the scenes where he’s mucking about with test tubes or stalking about a room are superbly played. Clearly, Gillette’s understanding of Holmes—his imagining and/or adapting of Holmes—chimes with that of our own era over a century later. Not only this, it’s almost certainly helped define the look and mood of many subsequent Holmeses. Gillette’s play would be readapted for John Barrymore as Sherlock Holmes (1922) and influence countless other versions later. (Other writers have surely asked even bolder questions than Gillette’s: “May I marry Holmes?”—and had no need to wait for Conan Doyle’s reply.) It’s strange that Gillette’s dramatic construction—the excess of characters, of melodramatic bustle—is so at odds with his performance. On screen, he’s so calm, cool, collected. He can command a scene even by doing nothing. Which is not to say he’s without humour or wit. There’s a very pleasing smirk (nothing more than a turn of the lips) that we see whenever he has outwitted one of the villains. (Strangely, these moments reminded me of Rupert Everett as Holmes in the one-off BBC drama Sherlock Holmes and the Case of the Silk Stocking (2004). Something about the height, presence, and control of Gillette—coupled with the hint of cool smugness—brought Everett to mind.) So, here’s to William Gillette the actor—but not the dramatist.

The version released by Flicker Alley is the restoration from 2015. This was based on the only surviving version of the film, a print found in Paris of the French serialized version from 1920. Strange that this should be the only copy that survives. For as a serial, the film surely doesn’t work: it’s so meandering, it lacks the structure or cliff-hanger endings of a true multi-part drama. Next to the contemporary serials of Feuillade, Sherlock Holmes is a pale crime thriller indeed. By 1920, the time of its release in France, it must have seemed rather old fashioned. But in its favour is that the print is gorgeous to look at. The film is richly photographed: the textures are thick, deep, and enhanced by the tinting. The images have real presence. But the drama does not.

Paul Cuff