After a day of urbane, light-hearted musical comedy, Day 3 of Bonn takes us to the streets for poverty and vagabondage…

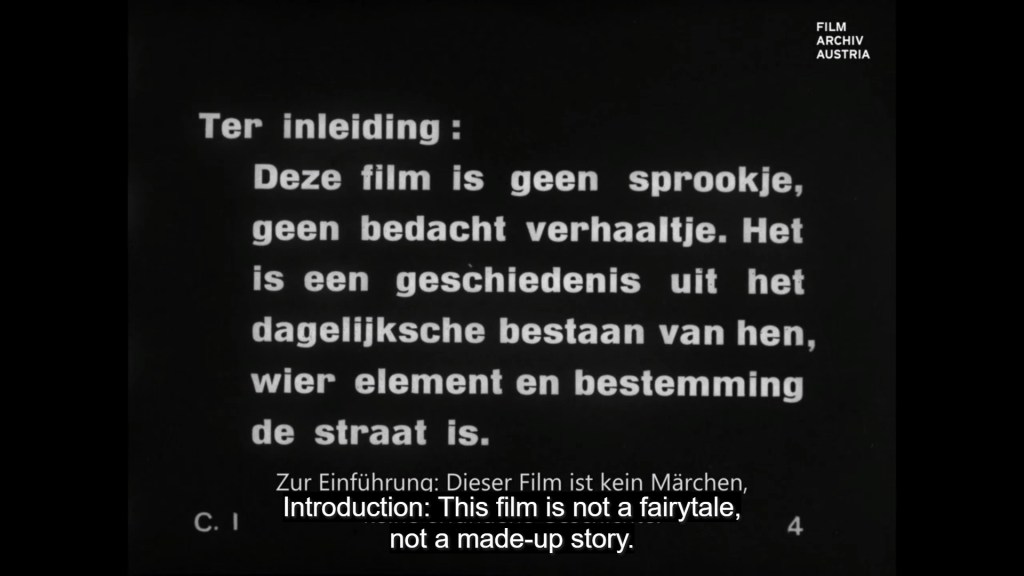

Der Vagabund (1930; Aut.; Fritz Weiß). The opening titles tell us that this is a story “taken from everyday lives”, as recounted to a journalist. The prologue begins with the sight of a vagrant’s body being found in a country ditch between Werder and Potsdam. All that’s found with him is a self-penned poem, an enigma that sets the journalist on a journey to the homeless shelter and the underworld of the unemployed and destitute. What follows is both an account of the journalist’s investigation and the stories he hears from the “vagabonds” themselves. What account of the “plot” I can give is necessarily brief: the film frames its narrative with the journalist visiting shelters and listening to personal accounts of vagrancy and homelessness. The main story becomes that of a man’s journey through Austria, where he encounters the uncaring attitude of many in society. Put like this, Der Vagabund sounds prosaic. But the structure and its cinematic realization are very striking, and the film is filled with amazing images of people and places.

From the outset, director Fritz Weiß provides some beautifully composed images of the landscape, the stillness of which is then offset by the handheld camerawork that brings us up-close to look at lived reality. Soon the camera is perched behind the journalist as he speeds into the city, where there are some amazing shots of the bustling streets that whiz past the car. Alongside the journalist, we visit the shelters and inspect the occupants. We see the vagrants strip and get inspected for lice, then shower. The faces and bodies are palpably real. (When the camera tracks past the vagrants as they eat, one of them shelters his face from the camera, as if ashamed or fearful of being seen.) There are powerful, often quick montages of details: the faces, the bodies, the clothes of the vagrants; or the watches, the coats, the hats left hanging in the shelter.

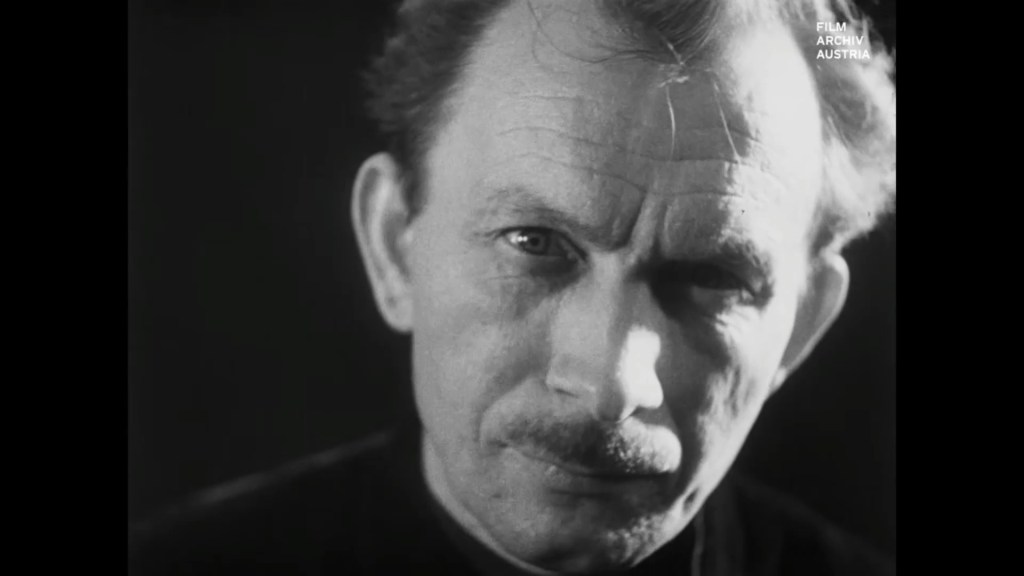

The film begins to give us some context for these people. We meet Gregor Gog, “the vagrants’ leader”, who gets an amazing introductory close-up in which he stares at – almost through – the camera. It’s a challenging look, one that demands we pay attention; it’s also a kind of question: what are we thinking when we see the vagrants on screen? There is a series of cutaways to the unemployed, drunks, petty thieves. We see their faces, are given little vignettes of their actions and habits. There are scenes in which we see the sign language by which their “brotherhood” communicates – chalked symbols on the walls if houses where they have found, or not found, help or food. The film thus gives us a sense of community, of commonality, between these otherwise isolated, down-and-out individuals.

This leads me to think about the film’s structure, which I found very curious. The first section of Der Vagabund, discussed in my previous paragraphs, is based on articles which (within the film) is deemed “too theoretical” by the newspaper editor. Is this a kind of judgement on the style of the film we have just seen? As if in reaction, the film shifts register. The editor wants “life stories”, and that then is what we are given by the film. Though it is carefully framed via the journalist’s interview, what follows is the story of one man who wandered through Austria. We see his temporary work, his moving from place to place, his interactions with locals in a smith, a farm, and on the road. We also see a glimpse of his time with a woman, of a shelter in Austria for other vagrants. Throughout, the film intercuts between this inner narrative and the framing narrative of the journalist interviewing the vagrants. There is a pleasing tension between the real and the fictional, especially given how real even the fictionalized sequences look. This is also felt in the rhythm of the editing. While earlier sequences have some swift montage of faces and illustrative scenes, when we are on the road with the vagrant in Austria there are more long shots/takes of his travels. It’s always a pleasure to roam about in the past like this, and this film’s rambling itinerary is the perfect way to see little pockets of history that you would other never see. There are beautifully composed images that show us the sweep of mountains and valleys. Though the film always gives us a contrast between the richness of the summer meadows and the rags and dirt of the traveller.

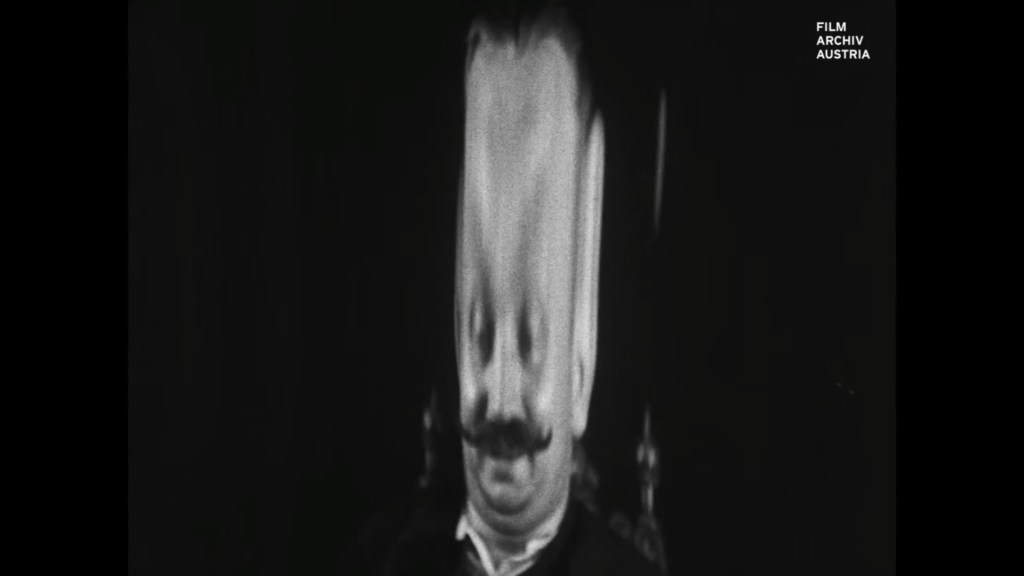

The film’s mode is not solely naturalistic, as there is a trippy dream sequence in which the vagrant character imagines himself tried and executed by the bourgeois bullies he has encountered on the road in Austria. It’s a wonderfully strange interlude, with a bleak edge: he imagines himself being hanged in a kind of forbidding, expressionist landscape. And “naturalist” doesn’t mean this film is so austere that it lacks lyricism or poetry. As I’ve said, there are some beautiful shots – beautifully composed and photographed – throughout the film, especially in the Austrian countryside. There is also a delightful sequence of shadow puppetry, improvised by the main character on the wall of the prison cell he shares with another vagrant, who is ill and lying in bed. The setting is realistic, but it finds a way of expressing something more personal than the set-up might suggest. The scene is silly and sad and touching all at once.

Der Vagabund ends with a montage of people from all classes pouring over the journalist’s articles in the newspaper Tempo. The motage then begins to intercut these scenes of reading with the “march” of the vagrants. To these shots are superimposed a vision of Gregor Gog giving a passionate speech. It was curious to see Gog emerge as a kind of heroic leader in this final montage. Though he is a real figure, playing himself on screen, his appearance at the end of the film is much more like that of a work of Soviet propaganda. Are we to read this as a promise of reform? A threat of revenge? A call to arms? It might be all three, and it is a surprisingly punchy end to Der Vagabund. Like the bourgeois readers of Tempo on screen, the media we consume is coming to life and confronting us with reality – demanding we think, reflect, react. Though the images stand comparison with numerous scenes in Soviet fiction films of this period, it also reminded me – with its confrontational crowd marching towards the camera – of Abel Gance’s J’accuse! (1919). The realization of the imagery is not as developed and sustained in Der Vagabund as in either these French or Soviet counterparts, but perhaps that is to its advantage. In such a film, I’d rather be won over by naturalism or lyricism than lectured or beaten over the head with crude slogans or overly tooled editing.

I should add that since watching the film I looked up Gregor Gog (what a name!), and I see that he led quite the life. From a working-class background, he ended up being drafted into the German army, where he was court-martialled during the Great War for his political activities. Mixing in an anarchist-communist milieu in the 1920s, he came to lead the “Vagabond Movement” (Vagabundenbewegung) and edit their mouthpiece publication, Der Kunde, which we see in the film. After 1933, he was arrested by the Nazis, escaped, fled to Switzerland, was expelled to Russia, spent time there in a labour camp, tried to become a novelist, and ended up dying in a sanatorium in Uzbekistan. Der Vagabund thus gives us a vivid glimpse into this corner of interwar Europe and its political movements. That said, Der Vagabund is not a work of crude propaganda. It certainly has an anti-bourgeois attitude (per the film’s many negative portrayals of monocled officials, hypocritical housewives, and brutish burghers). But it is also poetic and rambling. Its very structure of a narrative within a narrative lends it a picaresque quality, a slightly ramshackle form that loosens any sense of the viewer being lectured. A couple of years ago, I watched another low-budget socialist film, Brüder (1929), which was far cruder in its messaging – and (despite much beautiful location photography) less skilled in mobilizing either its lyrical, naturalist elements or its fictional, narrative elements. Der Vagabund is altogether a more interesting and more successful film.

The music for this presentation was by Filmsirup (Matthias André and Michi Hendricks) on piano and electric guitar. I found this extremely sensitive and sympathetic to the film. The rhythm was perfectly in match with the action, though “action” is often not the right word. Much of the time, the film follows characters who are killing time, mooching or loitering with or without intent. The music finds way of matching these sections very well. The dotted rhythms follow the vagrants as they walk along, slow down, dawdle, come to a halt, and resume again. The plash of water in the shower and the shattering of glass get their own moments in the music, just as the flashes of anger or dips into resignation of the characters are felt. I imagine this might be a difficult film to accompany, but Filmsirup do a very admirable job.

In sum, I found Der Vagabund an extremely interesting and engaging experience. Realistic and poetic, inventive and provocative, it’s a fascinating film. The restoration by Film Archiv Austria, based on a Dutch copy of the film, is beautiful to look at. A rich a rewarding film, with a pleasing musical accompaniment. A rich and rewarding film, with a pleasing musical accompaniment. Just the kind of thing you hope to discover at a festival. Bravo.

Paul Cuff