This week, I’m writing about not being able to write. I’d love to be telling you all about the beauties of Holger-Madsen’s film Der Evangelimann (1923), but all I can do is write about my entirely unsuccessful efforts to find a copy. While I am therefore unable to offer much insight into the film itself, I hope to offer some reflection on the intractable difficulties of writing about film history – and finding it.

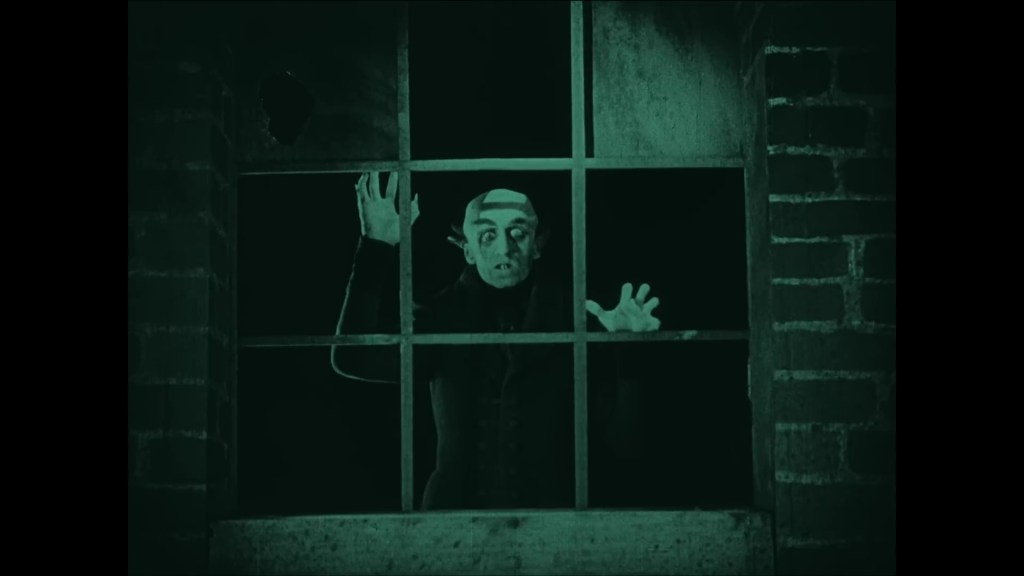

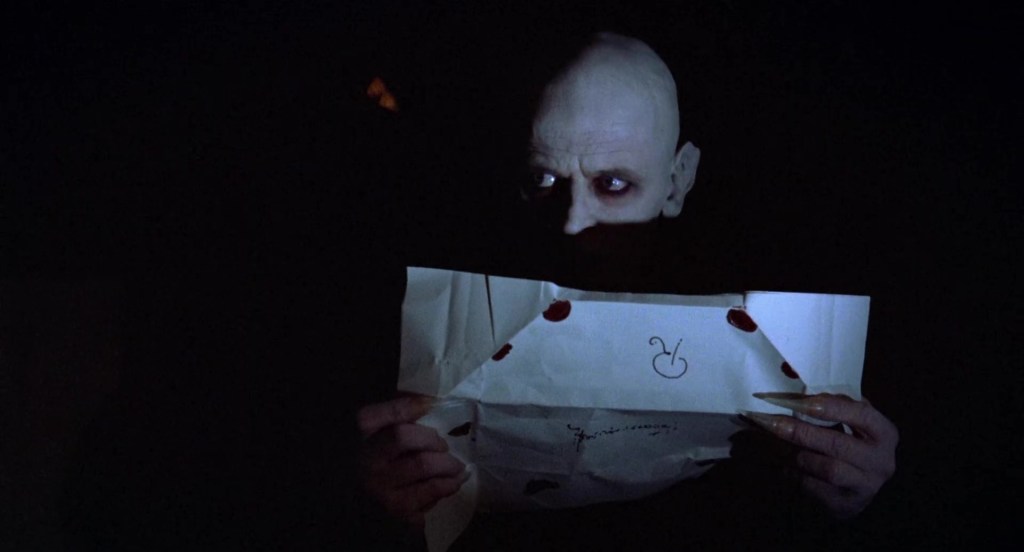

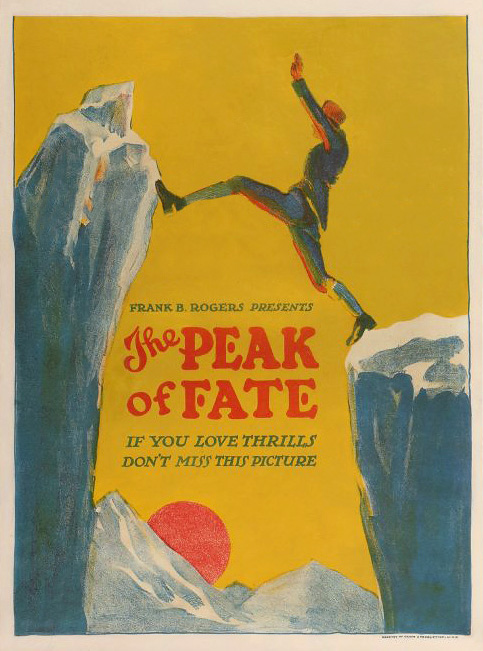

Why am I interested in Der Evangelimann? Well, as previous posts indicated, I have a growing curiosity about the work of Paul Czinner and Elisabeth Bergner. I have a longstanding project on their Weimar films, but I am also interested in their work before their first collaboration in 1924. Der Evangelimann was Bergner’s first film role, and her only pre-Czinner work for the cinema. This Ufa production was made in Germany but was directed by the Danish filmmaker Holger-Madsen and premiered in Austria in December 1923. Contemporary reviews were mostly favourable, but since its general release in 1924 it has virtually disappeared from the record.

I am also interested in the cultural background to Der Evangelimann. The film was based on an opera of the same name, composed by Wilhelm Kienzl (1857-1941). As even semi-regular readers of this blog may be aware, I am a devotee of late romantic music – and obscure operas by lesser-known composers have their own attraction for me. Since it swiftly became apparent to me that Der Evangelimann was going to be a difficult film to see, I turned my attention to finding a recording of the opera. As it turned out, Kienzl’s music was an absolute delight. A pupil of Liszt and a devotee of Wagner, by the 1890s Kienzl had become a successful composer and music director in various central European cities. Der Evangelimann (1895) was his greatest hit and became a regular production for opera houses into the first decades of the twentieth century. However, Kienzl never produced another opera that established itself in the repertoire to this extent, nor did he write much in the way of substantial music in other genres. By the 1930s, he had withdrawn from active work and by the time Europe emerged from the Second World War he was dead, and his work largely neglected. (His support for the Nazi takeover of Austria in 1938 cannot have helped his posthumous reputation.)

The opera Der Evangelimann is a pleasing blend of late romanticism with a touch of verismo (i.e. something rather more realistic than romantic drama). The libretto, adapted by Kienzl from a play by L.F. Meissner, is also a kind of ethical drama. Act 1 is set in 1820 around the Benedictine monastery of St Othmar in Lower Austria. The monastery’s clerk Matthias is in love with Martha, the niece of the local magistrate Friedrich Engel. Matthias’s brother Johannes is jealous of this romance, since he covets Martha for himself. Johannes betrays the lovers’ secret relationship to Friedrich, who furiously dismisses Matthias from his job. Seizing his chance, Johannes proposes to Martha, but he is angrily rejected. Matthias arranges with Martha’s friend Magdalena that he will meet his beloved late one evening, before he leaves town to seek work elsewhere. Their nocturnal meeting is witnessed by Johannes, who storms away in a fury of jealousy. As the lovers say a sad farewell, a fire starts in the monastery. Matthias tries to help but is swiftly blamed and arrested for the crime. Act 2 is set thirty years later, when Matthias returns to St. Othmar. He has spent twenty-five years in prison, after which he became a travelling evangelist, preaching righteousness and justice. He encounters Martha’s old friend Magdalena, who now looks after the ailing Johannes. We learn that Martha drowned herself rather than submit to Johannes’s proposal, and that Johannes has since attained great wealth but is haunted by enormous guilt. Magdalena ushers Matthias to see Johannes, who receives Johannes’s dying confession of guilt for the fire. Matthias forgives his brother, who dies in peace.

Kienzl’s opera is gorgeously orchestrated and contains at least two rather wonderful melodies. The most famous, “Selig sind, die Verfolgung leiden um der Gerechtigkeit willen”, is Matthias’s evangelist hymn. Kienzl, knowing he had written a good tune, cunningly makes Matthias teach a troupe of children this melody on stage. We thus get to hear the melody several times in a row, and it becomes the leitmotiv of reconciliation and forgiveness between the brothers. But my favourite scene of the opera is in Act 1. Rather than a set-piece number, it is a scene of anxious, hushed dialogue between Mathias and Magdalena. They are arranging Matthias’s final meeting with Martha before he leaves, and as they talk the bells are ringing across town for vespers. Kienzl creates a spine-tingling atmosphere that has remarkable depth of sound: from the slow, deep ringing of the cathedral bell to the warm halo of strings, then to the bright chiming of a triangle. A simple downward motif is thus given greater emotional resonance: you can sense the space and warmth of the evening, but also the sadness of departure, the steady pressing of time upon Matthias. In Act 2, when Matthias meets Magdelena again, the midday bells sound: suddenly, the scene evokes the past through an echo of its warm, chiming orchestration. It’s a beautiful scene, perfectly realized. (At this point, I pause to recommend the 1980 recording of Der Evangelimann conducted by Lothar Zagrosek. It has a great cast, too: Kurt Moll, Helen Donath, Siegfried Jerusalem. Though the EMI set is out of print, it is readily available second-hand. A must for anyone interested in out-of-the-way late romantic opera.)

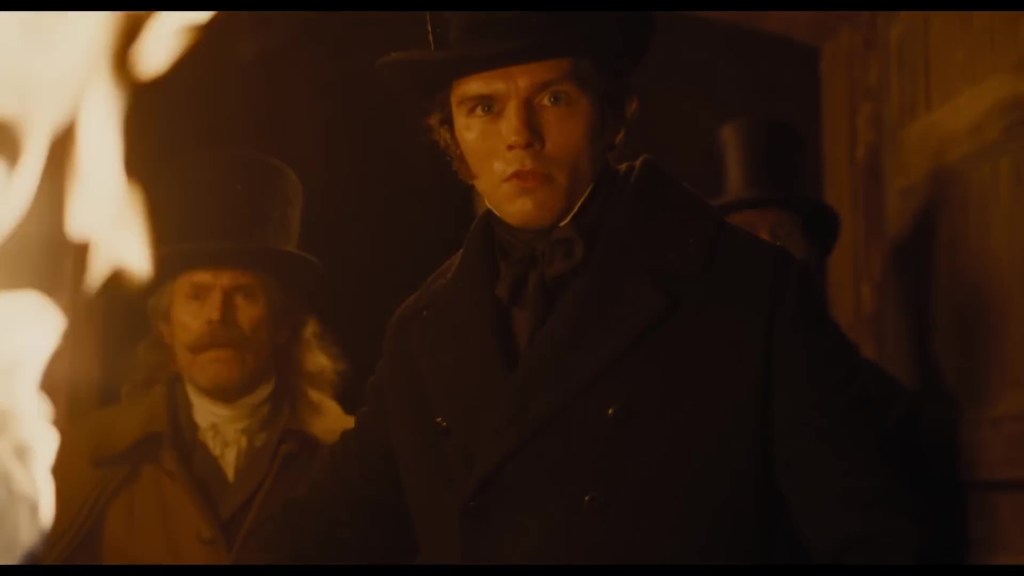

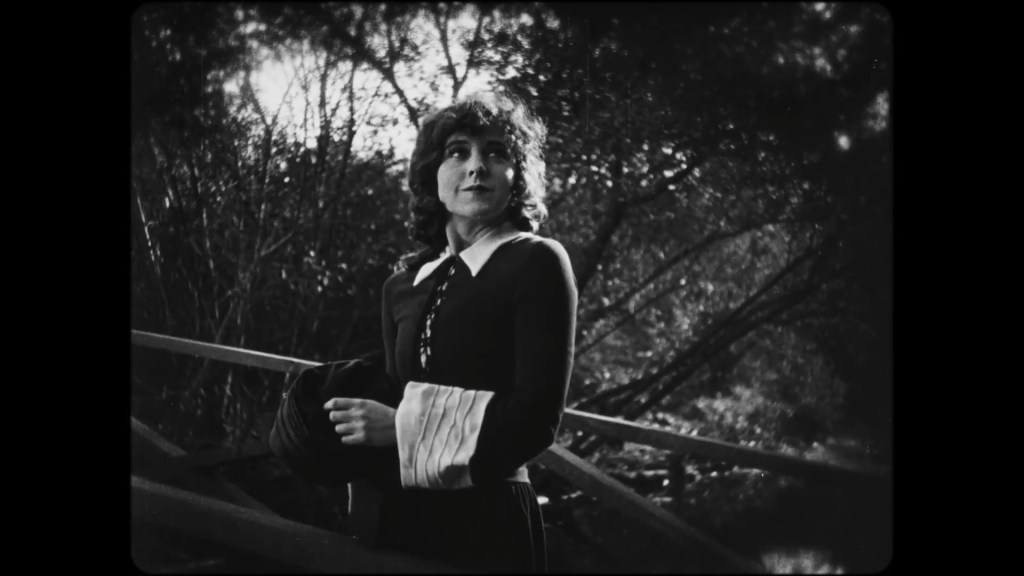

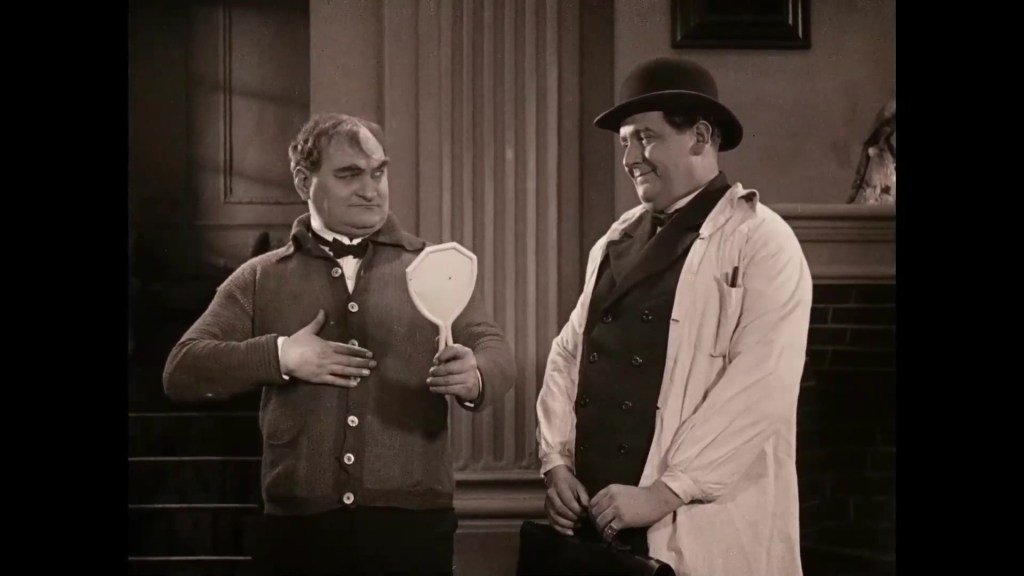

The 1924 film maintains the same basic plot and setting as the opera, though it has one or two curious departures. Per the opera, the first part of the film replicates Mathias (Paul Hartmann) and Martha (Hanni Weisse) being betrayed by Johannes (Jakob Feldhammer) to Friedrich Engel (Heinrich Peer), followed by the fire in the monastery and Mathias’s arrest. Years pass, Martha has married Johannes and together they have a young daughter, Florida. Martha then discovers that Johannes was the real arsonist (when he talks in his sleep) and ends her life rather than continue in their doomed marriage. After her death, Johannes moves to America – leaving Florida in the care of Magdalena (Elisabeth Bergner). Twenty years after the fire, the dying Johannes returns to St Othmar – as does the newly-released Mathias, now known as “the Evangelist” due to his preaching of holy justice. After Magdalena and the teenage Florida (now played by Hanni Weisse) go in search of him, Mathias eventually meets the dying Johannes – who then confesses to his brother and receives forgiveness.

I initially pieced together a synopsis from those available via various online sources, plus evidence from contemporary reviews. However, online sources do not provide the sources of their information, and I was left uncertain of numerous details. After a more thorough searching of the documentation catalogue of the Bundesarchiv (Germany’s state archive), I located the German censorship report of July 1923. Thankfully, this had been digitized and made available for public access. (As have many such censorship documents from the period.) The censorship report includes a complete list of all the original intertitles for the film, together with an exact length (in metres) for each of the six “acts” (“act” usually being a synonym for reel). Though there is no accompanying description of the action (i.e. what’s happening on screen), the titles provide a much clearer picture of the film’s structure and action. The document demonstrates how significantly Holger-Madsen expanded the ellipsis between the opera’s original two acts. The film’s second and third acts are set after the trial and the first years of Mathias’s imprisonment, allowing a glimpse into the minds of both brothers and of Martha – and showing us Martha’s discovery of Johannes’s guilt, and then her suicide.

Yet even the list of titles leaves some aspects of the narrative unclear. The film’s invention of a daughter for Martha/Johannes allows Hanni Weisse a double role as both mother and daughter. But I am unclear as to what (if any) dramatic function Florida has to the plot (she is evidently not a suicide deterrent!), or how exactly Mathias’s return is handled. Does Magdalena have a crucial role in this, or does he find his way back by chance – or by his own volition? Does Mathias encounter Florida, and what is his reaction to seeing the spitting image of his lost love? The titles do not make this clear.

Would other documents help? I know that if I visit the Bundesarchiv collection in person, I can inspect a copy of the programme for Der Evangelimann which may (or may not) clarify the issue. But where else to turn? I cannot find evidence of the film being released in France, in the US, or in the UK, and thus cannot find any other easy source of a more elaborate synopsis or of additional still photographs.

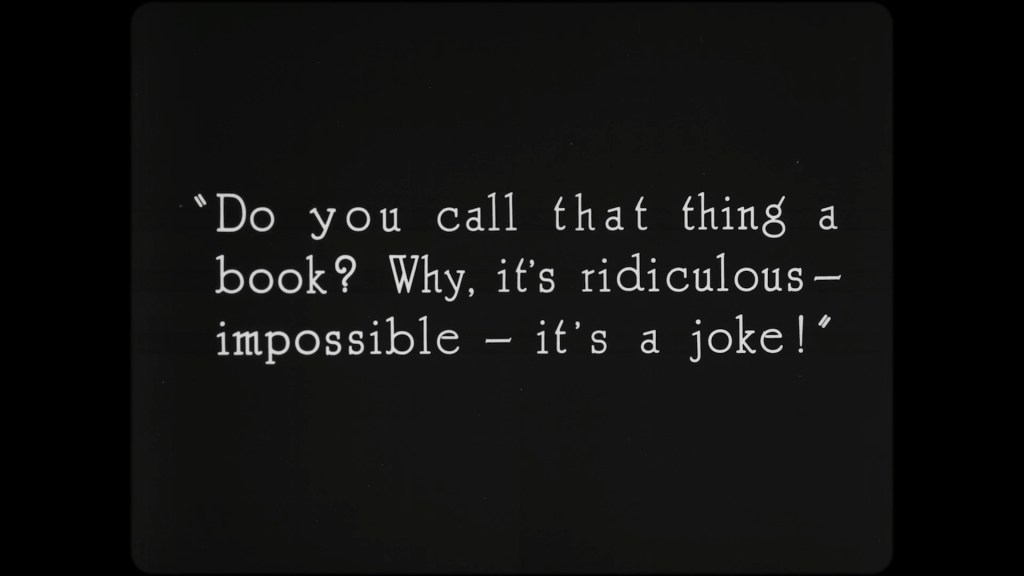

What of sources on Bergner? In Germany, there are many books devoted to her life and career on stage and screen – as well as her own memoirs. Ten years after the film was released, Bergner recalled being so disappointed with her experience on Der Evangelimann that it inspired her “contempt” for the entire medium of cinema (Picturegoer, 18 August 1934). In her later memoirs, Bergner claims that Nju (1924) was “my first film” (69) – erasing altogether the memory of Der Evangelimann. Those subsequent biographers or scholars to mention the film do so only in passing, but most accounts simply ignore its existence. The only account that even suggests familiarity with the film is that of Klaus Völker, which provides a meagre synopsis in its filmography and describes Bergner’s “slightly hunchbacked” appearance (398). Had Völker seen Der Evangelimann, or was this description based purely on publicity photos of the production? (The book contains only one other reference to the film, which repeats Bergner’s own grave disappointment in the role and the medium as a whole.)

Elsewhere, Kerry Wallach’s very interesting discussion of suicide in Bergner’s films (and contemporary Weimar/Jewish culture) makes passing reference to Der Evangelimann (19), but nothing that suggests familiarity with its content. Given Wallach’s interest in suicide and love triangles across Bergner’s films, it is odd that nothing is made of this first screen role being in a film that has both. I am curious, too, that Holger-Madsen chose to cast Bergner in the secondary role of Magdalena, since Martha is a much more interesting character – and her off-screen suicide (“in the waters of the Danube”, according to Matthias in the opera) would have directly foreshadowed the deaths of Bergner’s later characters.

All of which brings me to the nub of the issue: does any copy of Der Evangelimann survive? Has anyone seen it? Of course, the first source interested parties are usually advised to consult is the Fédération internationale des archives du film (FIAF) database. This is designed to be a collaborative database for information on archival holdings from across the world. Search here, and you can find the details of a film and a list of archives that hold material relating to it. That, at least, is the theory. In practice, it relies on data from its member archives that is not always available, complete, accurate, up-to-date, or forthcoming. I have long since accepted that the absence of a film on the FIAF database does not mean it is absent from the archives. This acceptance brings hope but creates other problems.

The next step, at least for a German production, is the usually (but not always) reliable filmportal.de. It is usually a decent indicator of the film’s survival in German archives and will also list the rights holders to the film and/or any restored copies. In the case of their page on Der Evangelimann, it lists the rights holders as the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung – the inheritors of much German cinema of the pre-1945 era. The FWMS lists details of the film on their website but (having asked them) they do not themselves possess any copy. Such is often the case, where the legal possession of a film does not coincide with the physical possession of a copy – or even the guarantee that a copy exists.

Where next? Well, the Bundesarchiv helpfully provides an accurate database of its film holdings – but this too yields no copy of Der Evangelimann. Various catalogue searches and archival contacts in Germany, Austria, the UK, and Russia have likewise yielded no result. Given that Holger-Madsen was Danish, I did also consult the Danish Film Institute about the film – but Der Evangelimann is not even listed on the DFI filmography of Holger-Madsen’s work, and they profess to have no copy. (Or at least, did not profess so to me.)

If Der Evangelimann had been restored, it would likely appear on more archival or institutional catalogues available online. But it seems scarcely to have made any mark on film history before proceeding swiftly to oblivion. Indeed, the only record I can find of any screening since 1924 was at the Internationales Filmfestival Mannheim-Heidelberg in 1963, where Der Evangelimann was part of a retrospective of Bergner’s work. Was this a complete print? Was it even shown, or just listed as part of the line-up? (Needless to say, I have contacted the IFFMH to see if they have any record of which archive loaned them the print, but I have not yet heard back.)

My only remaining option is to contact every film archive in the world, but there is no guarantee (as I have already discovered) that any of them will reply to a private researcher undertaking a wild goose chase. If an institution, restoration team, or legal rights holder were to make this inquiry, I imagine the process would be much more likely to yield results. As an individual, I have only a handful of contacts in the archival world, and limited resources of time, money, and patience to feed into this search. I cannot issue a convenient “call for help” that summons responses from across the world.

All of which makes an illustrative example of the problems of film history. What I have experienced scouring public resources for traces of Der Evangelimann is a frequent and frustrating instance of a common issue. The film may well exist in an archive, but without any publicly available acknowledgement of its status it might as well (for the purposes of film history and film historians) not exist. That which cannot be seen cannot be studied. It is also frustrating that no scholar on Bergner has ever taken care to admit either that they have not seen the film, or that the film does not exist – and that therefore future scholars should not waste time trying to locate it. Filmographies are infinitely more useful if they include information on a film’s original length (in metres, not duration), together with its current restorative status in relation to its original form of exhibition. These are quite basic facets of film history, but it is amazing how rarely scholars ever cite them – or are required to do so. (I am myself guilty of this.) As regular readers will know, it is a bugbear of mine that many restorations and home media editions likewise provide viewers with so little information on the history of what we are actually watching. It perpetuates a cycle of missing information: the material history of a silent film – the most literal evidence of the medium itself – is too often taken for granted and simply left out of its presentation, either on video or in written texts.

In the case of Der Evangelimann, a century of critical and cultural disinterest has left me with very little evidence to go on. Does the film survive? I do hope so. Even if it is a failure, and even if Bergner’s performance awful, I just want to see it and find out. A film doesn’t have to be a masterpiece to deserve recognition and restoration. I just want to see it! I will continue to pester archives, but in the meantime I suppose I can also pester you, dear reader. Do you know anything about where a copy of Der Evangelimann might be held? Any information would be most gratefully received.

Paul Cuff

References

Elisabeth Bergner, Bewundert viel und viel gescholten: Elisabeth Bergners unordentliche Erinnerungen (Munich: Bertelsmann, 1978).

Klaus Völker (ed.), Elisabeth Bergner: das Leben einer Schauspielerin (Berlin: Hentrich, 1990).

Kerry Wallach, ‘Escape Artistry: Elisabeth Bergner and Jewish Disappearance in Der träumende Mund (Czinner, 1932)’, German Studies Review 38/1 (2015), 17-34.