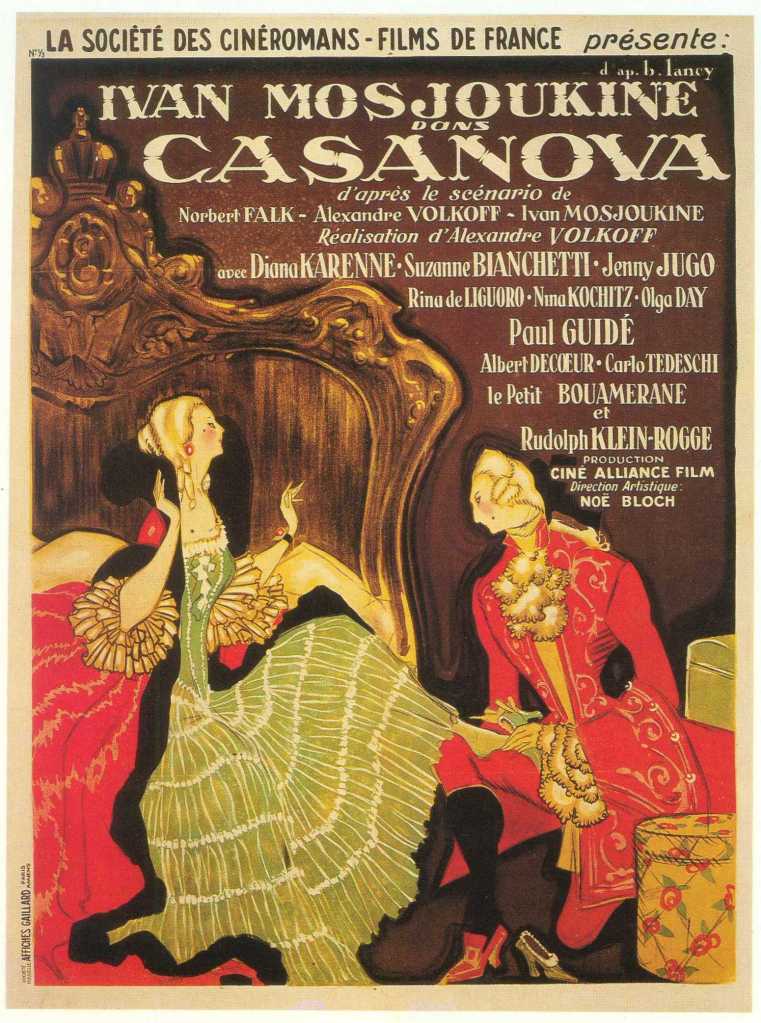

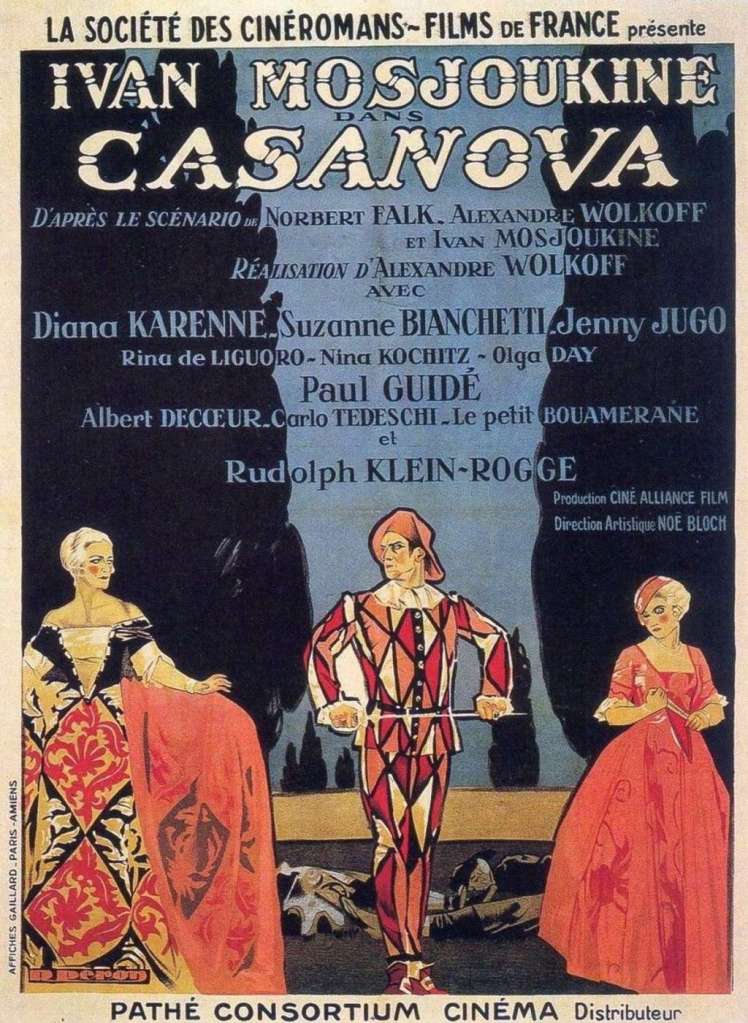

In 1926, Ivan Mosjoukine was at the peak of his career. He had just starred as the titular lead in V. Tourjansky’s Michel Strogoff (1926), an epic adventure film that proved a success in both Europe and Hollywood. A contract with Universal was the result, but Mosjoukine would make one last film in France before he left for America. It was to be produced by Ciné-Alliance, a company founded by Noë Bloch and Gregor Rabinovitch, with financial support from the Société de Cinéromans and UFA. In all aspects this was to be a pan-European film, with cast and crew coming from France, Russia, Germany, Italy, Austria, and Poland. The director, Alexandre Volkoff, had come to France with Mosjoukine and a group of fellow Russian emigres at the start of the 1920s. Together, they had made the serial La Maison du mystère (1922) and the features Les Ombres qui passent (1924) and Kean (1924). Across five months of shooting in August-December 1926, Casanova was shot on location in Venice, Strasbourg, and Grenoble, and in studios at Billancourt, Epinay, and Boulogne. Six months of post-production followed, including the lengthy process of stencil-colouring several sequences, before the film’s premiere in June 1927—but it wasn’t until December 1927 (a full year after shooting ended) that it was released publicly in France. By this time, Mosjoukine had already gone to Hollywood—and come back. The one film he made there, Edward Sloman’s Surrender (1927), was hardly worth the trip. (“Catalog it as fair to middling”, wrote the terse reviewer in Variety (9 November 1927, p. 25).) So Casanova was both the last film Mosjoukine made before his Hollywood debacle, and the first film he released on his return to Europe.

The film follows Casanova’s succession of adventures across Europe. In Venice, we see his affair with the dancer Corticelli (Rina de Liguoro), his abortive duel with the Russian officer Orloff (Paul Guidé), and his assignation with Lady Stanhope (Olga Day). Harried by the gendarmes of Menucci (Carlo Tedeschi) for his debts and supposed involvement in the “black arts”, he travels to Austria. There he encounters Thérèse (Jenny Hugo), whom he tries to save from her brutish captor the Duc de Bayreuth (Albert Decœur). Thwarted in his attempt, he encounters Maria Mari (Diana Karenne) and, in disguise, follows her path into Russia. In Russia, he charms the Empress Catherine (Suzanne Bianchetti) and witnesses her overthrow of her mad husband, Tsar Peter III (Klein Rogge). Re-encountering both Orloff (Catherine’s lover) and Thérèse, Casanova finds himself on the run once more. So he returns to Venice, where it is carnival season. Here he finds both Thérèse and Maria, as well as the authorities and his old enemy Menucci. Maria, furious at Casanova’s interest in Thérèse, ends up helping the authorities capture Casanova. However, with the help of Thérèse, he escapes from prison and sets sail for adventure beyond Venice…

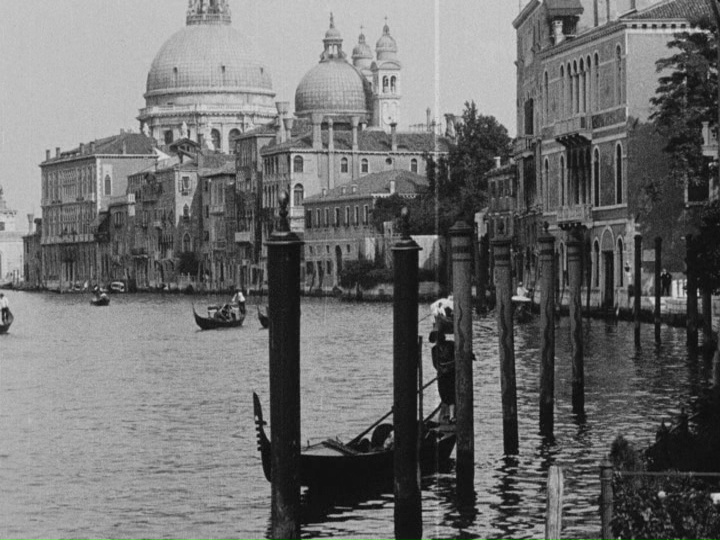

First thing’s first: Casanova looks beautiful. The Flicker Alley Blu-ray presents a new version of a restoration originally completed by Renée Lichtig in the 1980s. Lichtig herself spent years tracking down various prints of the film to reassemble, including one reel of remarkable colour-stencilled material. I had seen Lichtig’s reconstruction of Casanova on an old VHS and was tantalized by the glimpses of sets and locations on screen. But though I knew the story, I wasn’t prepared for just how good the film now looks in its latest digital transfer. The sets are sumptuous, as are the costumes. This is a world on screen that is simply and absolutely pleasurable to behold. The scenes shot in Venice are a joy just to look at: Volkoff composes his exteriors with great care and fills his scenes with life. His cameramen were the experienced Russians Fédote Bourgasoff and Nicolas Toporkoff, together with the Frenchman Léonce-Henri Burel—one of the greatest cinematographers of the age. Thanks to a production that stretched from summer to winter, the film also gives us all the seasons: from the sweltering city of stone in Venice to the hazy forests of Austria and the snows of Russia.

Among all these exteriors, the nighttime sequence at the carnival is the most captivatingly beautiful: here are lanterns blushing pink, fireworks bursting red and gold, costumes glowing in otherworldly yellow.

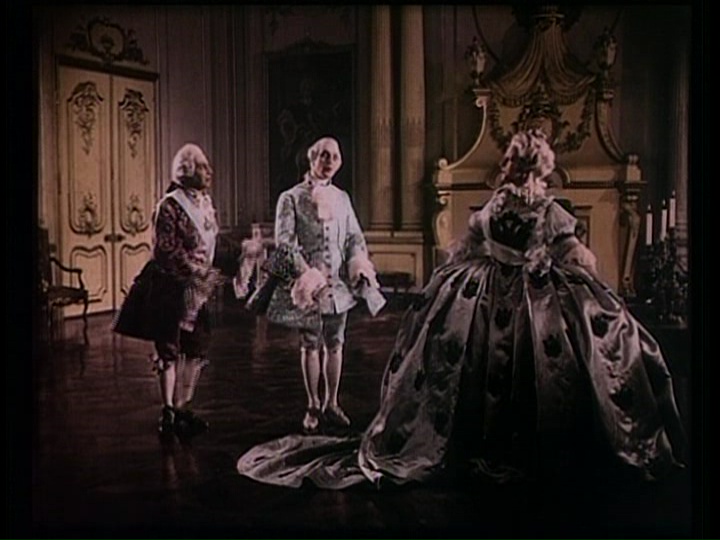

Sadly, the other colour sequences in the film remain missing. Extracts from one such sequence—the grand ball in Catherine’s court—appear in colour in Kevin Brownlow’s series Cinema Europe (1995). That material comes from a 16mm print in Brownlow’s own collection, which evidently wasn’t used for the new restoration of Casanova. Perhaps the restorers did not know of it, or else the 16mm print is too fragmentary (or not high enough quality) to incorporate into the 35mm material. (Actually, looking at the image captures side-by-side, I see that in fact the 16mm copy shows more information in the frame than the 35mm copy used for the Lichtig restoration. Was this taken from an earlier/better source than the 35mm?) Either way, it’s a shame that this—and any other colour-stencilled scenes that may have existed—do not now survive. (I’ve always thought that the opening credits—Casanova’s name lit-up like fireworks—would have at least been tinted, if not colour-stencilled. The scene uses footage from the nighttime firework display that, later in the film, is elaborately stencilled in colour. Wouldn’t this film show off how colourful it is from the very opening images?)

But is Casanova anything more than eye candy? What kind of film is it? Well, it isn’t quite a biopic, it isn’t quite a romantic melodrama, it isn’t quite a historical epic, it isn’t quite a comedy, it isn’t quite a fantasy. It’s a blend of all the above. It’s a picaresque, episodic adventure with various subplots tying together the lengthy (159 minutes) narrative. And despite being a “light” film, it isn’t without a kind of cumulative substance.

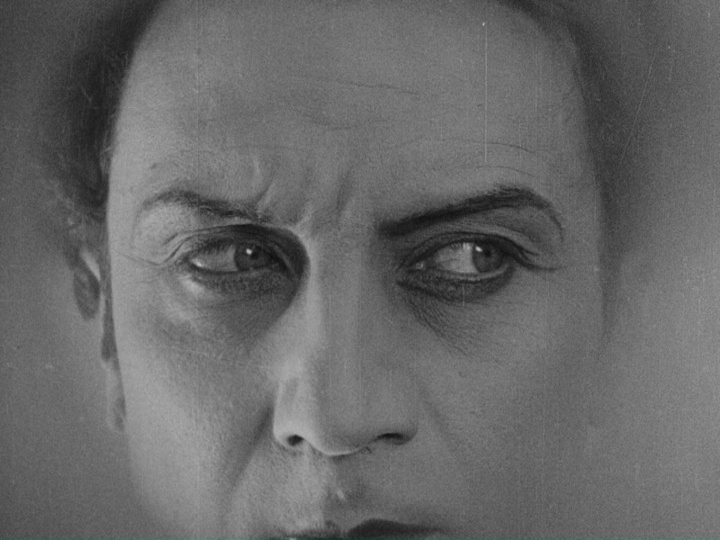

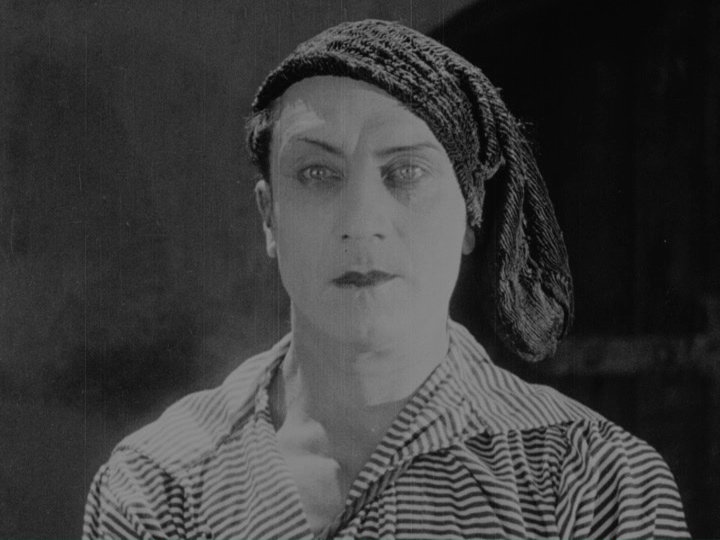

The heart of the film is Ivan Mosjoukine. He revels in his changes of costume, his multiple roles as lover, fighter, comedian, magician. And the film plays along, performing trickery of its own to help him make his escapes.

Early on, he frightens Menucci by performing a magic trick. Growing to enormous proportions, he puffs out into an absurd, leaping balloon in wizard’s costume—his face a bloated ball, tongue waggling from cavernous mouth. The film reveals the outlandish mechanics of the trick within the world on screen (his two female servants inflate him with hidden tubes), but also executes its own cinematic trick: for an in-camera dissolve hides how Casanova removes the skin-tight face mask that enables his wizardry. Mosjoukine even plays up this piece of subterfuge: at the end of the dissolve, he seems to shake off the effect of the transition. It’s as though he’s merged not just from a costume, but from the celluloid mechanics of the trick.

This scene is also emblematic of the number of jokes in the film. For despite the huge amount of money on show in its locations, sets, and costumes, the film doesn’t take itself too seriously. From farcical scenes of disguise, elements of slapstick, to delicate moments of performance, Casanova is full of humour. Most of it is good-natured, but one crude element is the way the film uses Casanova’s black servant Djimi (Bouamerane). Though Djimi gets some good laughs by his reactions to Casanova’s behaviour, he’s also subject to several jokes based on the colour of his skin. He’s often treated like an animal, at one point even being made to chew meat from a bone like a dog. That the child is in blackface hardly helps these jokes land.

But there is also plenty of visual sophistication. Volkoff also uses some inventive montage and photography for many sequences. There is extensive use of mattes, masking, superimpositions, soft focus—as well as tinting, toning, and colour—to manipulate the images, creating atmosphere and mood. The camera is mobile (with some subtle and some dynamic tracking shots), placed at interesting angles (e.g. dug into the ground to film the horses leaping overhead in the chase sequence), and even handheld (for the carnival dancers).

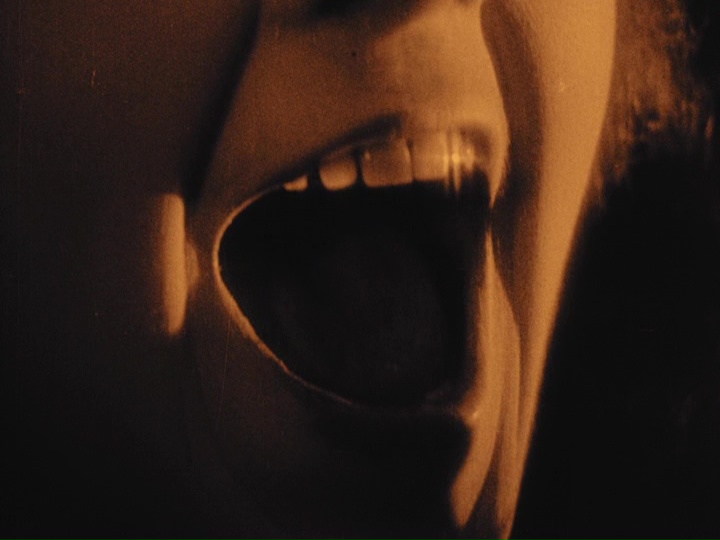

A notable sequence involving all these elements is in the Austrian section, where Casanova is in his room at night. He paces towards the camera, which keeps him in close-up by tracking backwards. Women fill his mind, and the screen: superimposed all around his head. (Again, think how difficult this is, technically: each image of each woman filmed separately, then the multiply-exposed celluloid re-exposed for the scene with Mosjoukine in the centre.) He bats them away, as though they were really there—and they are really there in the frame, after all. Then he approaches the crucifix on the wall, the camera tracking forwards to frame it in close-up. Is the rogue adventurer about to pray? Cut 180° to Casanova, who stands before us as if in confession. But instead of praying, his eyes immediately dart away from our gaze. He then nonchalantly flicks off two fake beauty spots from his cheeks. It’s a strange moment of reflection before the camera, which has taken the spatial place of the crucifix in front of him. Is he self-conscious before us? Before the cross? He clasps his fist and pounds his chest. But if this seems like the start of some kind of private emotional outpouring, it is swiftly allayed. For his eyes once more dart to one side and he cocks his head: he’s heard something. Intercut with Casanova in his room, Volkoff shows a series of brief glimpses into another space. Each of these images—bare feet running across a floor, a chair falling over, hands raised in fear, boots advancing, two figures wrestling—appears in soft focus, the diffuse lighting making each appear tangibly out of reach; these are visual equivalents of muffled sounds. Only the last image, of Thérèse’s mouth opening to scream as hands reach for her throat, is in strong contrast and clear focus. For this image is the visual cue for the piercing sound of her scream. Casanova rushes in to save Thérèse from the Duke of Bayreuth.

This sequence has captivating visual appeal, and it points to the greater emotional attachment Casanova has for Thérèse—as does the elaborate tracking shots of them racing through the woodland roads, her narration appearing in superimposed titles over the passing forest. Casanova may be a rogue, but he also performs good deeds and is susceptible to real feeling. Earlier he has defended a beggar violinist against some rich drunks, and later he risks his life—and abandons his lover—for the sake of Thérèse. Their last scene together intercuts extended close-ups of their faces, Casanova slowly growing more teary-eyed. Mosjoukine’s performance in this shot is strange and beguiling: his eyes narrow just as the tears seem about to fall; it’s as though he’s both willing and curtailing his tears at the same time. It’s the one moment in the film where we get a glimpse of something deeper in his character.

On the theme of emotional tone, I must also discuss the new score for the film by Günter A. Buchwald. I first saw Casanova with an orchestral score by Georges Delerue, dating from 1985. Delerue treated the film as nothing more than a confection of pretty pictures: his music is repetitive, twee, and entirely without substance or interest. The Buchwald score is much more varied, inventive, and tonally adventurous. But I still don’t quite like it.

Buchwald’s score is for small orchestra, but he reserves the sound of this ensemble for the scenes of great drama or the beginning/conclusion of important sections of the film (e.g. the opening, the arrival in Russia, the return to Venice). In-between, the music has a more chamber-like sonority, with much use of the harpsichord. It follows the film’s incidental scenes with incidental music: frequent changes of gear, of mood, of timbre. Though Buchwald quotes various classical pieces (by Vivaldi, Tchaikovsky, Monteverdi), it keeps a sense of ironic detachment from the period of the film: this is neither a recreation of the sound-world of 1760s Europe, nor a recreation of the sound-world of 1920s France. (The original score for the film in 1927 was arranged by Fernand Heurter, and I can find absolutely no information about it at all.)

The result is that the score often feels (to me) rather meandering. It doesn’t help that the orchestra—especially the string section—sometimes struggles to keep together. (I am assuming this is a performance issue and not a deliberate compositional choice.) The score frequently demands the highest register of the strings, which taxes the players’ cohesion. Certain passages (most noteworthy in the emotional climax of the film, when Casanova says farewell to Thérèse) sound scratchy and thin. Then again, in his liner notes to the Blu-ray, Buchwald points out that he sought an almost atonal aspect for some scenes, such as those in Russia with Peter III, so perhaps the astringency I noticed in many places was a deliberate choice. The score was recorded in January 2021, and Buchwald writes that the orchestra was playing for the first time in a year—and doing so with masks and social distancing. These are hardly ideal conditions for sightreading and performing a new score, so perhaps this is also evident in the recording.

What’s missing for me in the music is any kind of sincere emotional engagement. One might argue that this is the film’s problem: it doesn’t have great emotional depth or resonance, so why should the score? But the film is consistently beautiful and beguiling, qualities this score often lacks—indeed, qualities it seems to eschew. Rather than tie the film’s episodic narrative together, the music emphasizes its discord. The score spends much of its time ironically underlining the action. It’s often spiky, acerbic. When it assumes the musical style of formal elegance (the dance themes for scenes in Austria or Russia), it does so ironically: undercutting the rhythm with deliberate slurs or dissonant harmonies. In many ways, it’s the opposite of the Delerue score. The latter smoothed over any sense of drama or tension, whereas Buchwald emphasizes every possible discord.

Just listen to the way he orchestrates the escape of Casanova and Thérèse from the inn in Austria: continuous snare drum; high, angsty strings; Casanova’s main theme rendered dissonant; even the lovers’ kiss is accompanied by a solo clarinet melody that is hardly a melody at all. Everything is unsettled, anxious, chromatically restless. Or in the last part of the film, when Casanova sings to the crowd in the carnival: here Buchwald gives the trombone the part of the voice, but the trombone deliberately slurs and bawls, while a disinterested rhythm shivers through the strings. An intertitle tells us the crowd is spellbound by the singer, but the music sets out to undo any spell he might cast over us. This is a score working against the spirit of the film.

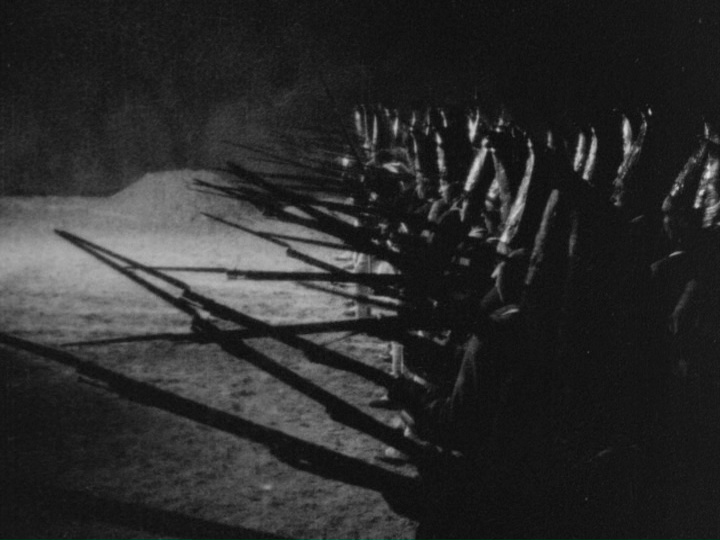

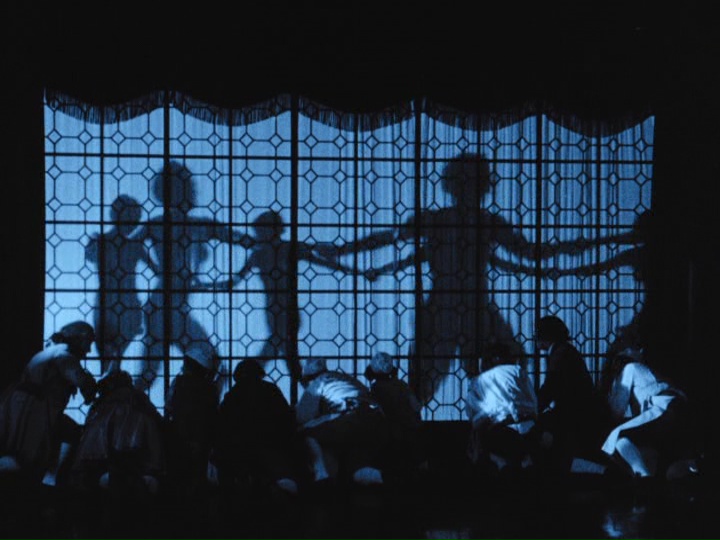

Though Buchwald’s orchestra includes both a mandolin and harpsichord, it avoids citing much music of the film’s period setting in the 1760s (i.e. the late baroque and early classical era). The only piece that is played in its entirety is the opening movement of Vivaldi’s Concerto alla Rustica (in G Major, RV151). This is used for the gorgeous “dance of the swords” sequence, where Volkoff combines elaborate lighting and composition to frame the dance in silhouette and shadow behind screens or cast upon walls. But the piece of Vivaldi used for this four-minute sequence is barely a minute long, so Buchwald not only has to repeat the entire movement but play this “Presto” at a pace so sluggish that it takes nearly twice as long as intended. Thus, the original impetus and shape of the music is changed in a way that makes it less effective for the sequence in the film. There is no climax, no sense of shape that matches Volkoff’s complex montage. The dance, after all, becomes more provocative and enticing—the reaction shots of the male spectators becoming more regular, more intense. (Lest it be thought that using such a well-known work is detrimental, for its inclusion in Cinema Europe in 1995 this same sequence was accompanied by Carl Davis’s arrangement of the third movement of “La primavera” from Vivaldi’s Le quattro stagioni. It works perfectly.)

This Vivaldi movement is the only lengthy musical citation in the film, and I’d be tempted to say the only sincere citation. Most examples are very brief, sometimes just a few bars in length, and serve as punctuation marks—often ironic. Thus, the opening theme of Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 4 (1878) appears in one of the climactic scenes in Russia, but no more of that piece is used again. It’s a kind of announcement of grandiloquent, romantic fate that the score has no interest in taking up and developing. Likewise, Buchwald quotes the Monty Norman/John Barry “James Bond theme” (1962-) for the moment when Casanova slides down a snowy slope to avoid his pursuers in Russia. I confess this moment made me writhe with displeasure. It struck me as emblematic of the way the score ironized the film more than it supported it. So too the way Buchwald uses Monteverdi’s opening toccata for L’Orfeo (1607) in the last section of the film. The delicious back-and-forth echo of sounds in this fanfare is transformed into the soundscape for a drunken tavern scene. Monteverdi’s rich major tones morph into the minor and slip out of rhythm; and the addition of a glockenspiel introduces a harsh, brittle sound that further destabilizes the music’s harmonic integrity.

I suppose what I’m trying to say is that this is a cold score for a warm film. Casanova is a fresco of fabulous settings, of rococo costumes, of comedy and romance. I’ve always imagined it being accompanied by something equally filled with warmth and colour. It occurs to me now that the film is a successful imagining of late eighteenth-century drama in a way that Robert Wiene’s Der Rosenkavalier (1926) is an unsuccessful imagining. I mentioned in my review that Richard Strauss’s score is in every way superior to Wiene’s filmmaking; the music for Der Rosenkavalier deserves to accompany something better. What it deserves to accompany, in fact, is Casanova! Strauss provides the kind of emotional richness (and sheer sonic beauty) that’s lacking in Buchwald’s score. But I do appreciate that responses to music are very personal, so it may be that others delight in and savour Buchwald’s score much more than I do. It’s just that I’ve been waiting to see Casanova in its best quality for much of my adult life, and I wish I’d been truly moved. And I feel I could have been moved with a different score.

Despite my musical reservations, I’m immensely pleased that Casanova has finally received a release on Blu-ray. I hope that the next Mosjoukine film to receive full restorative treatment will be Tourjansky’s Michel Strogoff, another work restored by Renée Lichtig in the 1980s. The copy I have (digitized in the mists of time from an archival VHS) features an orchestral score by Amaury du Closel, but I suspect that any future release will substitute it for something else. Closel’s music is strong, though it ignores many of the clear music cues on screen (bells, trumpets) in a way that irked me when first I saw it: Tourjansky’s montage deserves music that really engages with it. I’m curious if Michel Strogoff can offer a more substantial emotional world than Casanova. I’d love to see it in a version that does it full justice. If it looks anything as good as Casanova, it’ll be a real treat.

Paul Cuff