This week, I talk about Ilya Ehrenburg (1891-1967), a writer whose work I discovered through silent cinema. I’m a huge fan of G.W. Pabst’s Die Liebe der Jeanne Ney (1927) and was curious to read the novel on which it was based. After a long search, I tracked down an English edition of The Love of Jeanne Ney from 1929. Given the price tag of my copy, I was worried I would regret my purchase of this utterly obscure novel. But within a few pages, I was totally won over by the style and tone of the author. By turns humorous and brutal, charming and satirical, cruel and romantic, the novel is a superb read. Ehrenburg’s voice so appealed to me that I looked up what else he had written. It became apparent that the man was prolific, publishing numerous novels, reams of poetry, volumes of travel journalism, war reports, speeches, reviews – all in different languages: Russian, French, German, Yiddish… Of this ungraspably extensive bibliography, I found that none of his non-journalistic work was in print in English. Some of his wartime work remains available, in particular his report on the Holocaust in eastern Europe: The Complete Black Book of Russian Jewry, a collection of eyewitness accounts compiled with Vassily Grossman.

This situation was very different in the 1960s, in the post-Stalin cultural “thaw” (a term Ehrenburg popularized), when the author’s work was widely discussed in the anglophone world. It was in this period that he wrote his memoirs. Finding decent copies of all six volumes of this work was difficult, but I love a challenge. From bookshops across the globe, I amassed them all and read them across the course of last summer. Quite simply, Men, Years – Life (1961-66) is one of the most extraordinary memoirs I’ve ever read. It is almost unbelievable what this man experienced: from imperial to post-Stalinist Russia, from trenches in Spain to the skyscrapers of New York, from the cafes of Paris to the battlefields of the east, from writing poetry in garrets to making speeches at peace rallies, Ehrenburg experienced almost every conceivable facet of the early twentieth century. That he did not perish in the revolutions, civil wars, world wars, genocides, and multiple purges that he experienced is miraculous. “I have survived”, he writes in his opening pages, “not because I was stronger or more far-seeing but because there are times when the fate of a man is not like a game of chess played according to rule but like a lottery” (I, 7). As the title of his memoirs indicates, Men, Years – Life is a personal record of his era through the people he encountered. Amid his generosity to innumerable writers, artists, and fighters he met, the major events of Ehrenburg’s personal life sometimes slip in through devastatingly brief asides. (Thus, in passing, do we learn that his first wife leaves him for another man, with whom she raises their daughter Irma (I, 186).) If nothing else, it is an amazing record of the first half of the twentieth century, a time when “history unceremoniously broke into our lives by day and by night” (III, 89).

This week’s post, and my subsequent post, is a selected tour through some of Ehrenburg’s life and his relationship with cinema: cinema as culture, cinema as literary adaptation, cinema as a way of seeing the world.

Part 1: Early years

Ehrenburg was born in Kiev, a subject of the Russian Empire, to a Lithuanian-Jewish family. His first memories are of an era that would bring an unceasing flood of cultural shocks and revelations. “The twentieth century was under way”, he writes: “I remember one of our visitors telling us that soon a ‘bioscope’ would be opened and that they would show living photographs” (I, 30). For the adolescent Ehrenburg, the new century means other forms of revolution, too. He becomes involved in political activity associated with Bolshevism. Aged seventeen, he is arrested and exiled.

He arrives in Paris in December 1908, knowing barely any French – just an outré vocabulary drawn from the plays of Racine. With his unerring knack of finding extraordinary people wherever he went, he soon meets a raft of other local or exiled figures – from Lenin (“his head made me think not of anatomy but of architecture” (I, 69)) to Blaise Cendrars (“he was the yeast of his generation” (I, 170)), not to mention fellow avant-gardists Picasso, Modigliani, Rivera, and others. The writers and artists among them would meet at the Café de la Rotonde, a restaurant in Montparnasse where “we would gather […] in the evenings to drink, read poetry, make prophecies or simply to shout” (I, 171). Living in what amounted to almost debilitating poverty, Ehrenburg became a poet “because I had to” and a journalist “because I lost my temper” (I, 178). When he could afford it, he went out. In 1911 he attended the (in)famous premiere of Le Martyre de saint Sébastien, D’Annunzio’s stage collaboration with Debussy. He records being “infuriated by its mixture of decadent aestheticism and a kind of scent shop voluptuousness” (II, 128). (He didn’t realize it, but Abel Gance was there on stage, playing one of the extras.) Later, in the company of the painter Diego Rivera, Ehrenburg encountered a new kind of artist for the age:

Once at a small cinema Rivera and I saw a film actor I had never seen before. He smashed crockery and daubed elegant ladies with paint. We guffawed like everyone else, but when we had left the cinema I said to Diego that I felt afraid: the funny little man in the bowler hat exposed the whole absurdity of life. Diego replied: “Yes, he’s a tragedian.” We told Picasso to be sure to see the film with Chariot: that was the name the French gave Charlie Chaplin, as yet entirely unknown. (I, 199)

Then came the Great War, “a grandiose machine for the planned extermination of human beings” (I, 184). Ehrenburg volunteers to fight Germany but is rejected by the army doctor as unfit (“One cannot with impunity prefer poetry to beef for a period of three or four years” (I, 161)). So he becomes a witness, watching the old order disintegrate – and the violent forces this process unleashes. Europe’s civilization is merely a set of clothing now shed, its philosophy abandoned for bloodlust. For Ehrenburg, it is a swift and uncomfortable revelation. “I realised that I had not only been born in the nineteenth century: in 1916 I lived, thought and felt like a man from the distant past. I also realized that a new century was on its way and that it meant business” (I, 185). Europe was stepping “into the dark ante-room of a new age” (II, 101). And from the west, American culture floods in. When the US enters the war in 1917, the newspapers gush over the prospect not merely of American soldiers but American culture: “They extolled everything – President Wilson and Lilian Gish, American tinned food and the dollar” (I, 219).

After the war, Ehrenburg returns to the east. This part of his memoirs is among the most personal, since there was not enough political or cultural stability to sustain his creative life. Having always considered Kiev as his “home town”, in 1919-20 Ehrenburg realized how contingent the idea of “home” might be. “[The] Romans […] used to say Ubi bene, ibi patria: where it is good, there is your motherland. In reality, your motherland is even where it is very, very bad” (II, 75). Russia and much of eastern Europe was in turmoil. Kiev was at the centre of a civil war and changed hands several times. “Sometimes I felt as if I were watching a film and could not understand who was chasing whom”, Ehrenburg writes: “the pictures flashed by so quickly that it was impossible to see them properly, let alone think about them” (II, 80). Cinema here becomes a metaphor both for vision and for bewilderment – a kind of impediment to vision. Like silent films that were projected at faster-than-life velocities, lived history did not behave according to clock time.

The chapters that follow read like the flickering images Ehrenburg describes, passages of events so bewildering and terrifying that it is staggering that the narrator survived to narrate. Only when, for six months, the Red Army occupies Kiev is there a window of stability – at least for Ehrenburg. But even this interval is surreal, since he is charged with supervising “mofective children” (i.e. “morally defective” children). It was a form of re-education for the socialist utopia that beckoned. “The discrepancy between our discussions and reality was staggering”, Ehrenburg observes (II, 83-90). Utopia is postponed. The Reds are swept away. The Cossacks arrive. There is a pogrom. A disorganized medley of murder, mutilation, rape. As a Jew, Ehrenburg moves from hiding place to hiding place. Captured, he narrowly avoids being “baptized” (i.e. thrown into the ice-covered sea of Azov) (II, 95). He is among a flood of refugee in the Crimea, where he is starved and abused for being both a Jew and a Red. Then typhus strikes. His wife is a victim. She survives, but in what state?

After Lyuba’s temperature had gone down, a complication arose: she was convinced that she had died and that we were for some reason forcing a life after death upon her. With the greatest difficulty I got food for her and cooked it, my mouth watering, while she repeated: “Why should I eat? I’m dead, aren’t I?” One can easily imagine the effect this had on me; yet I had to go to the playground and play ring-a-ring-o’-roses with the children. (II, 101)

There follows a series of interventions random, comic, and horrifying. Ehrenburg escapes from the Crimea on a salt barge that he realizes is slowly sinking. He finds refuge in Georgia, then goes to Moscow. Having been nearly murdered by the Whites (for being a Red), Ehrenburg is now arrested by the Reds (for being a White). He is imprisoned, than released. Vsevolod Meyerhold invites him to head the organization of children’s theatre in Russia. But in 1921 Ehrenburg leaves Russia. He goes via Riga, Danzig, Copenhagen, and London to Paris – only for the French authorities to expel him to Brussels for being a suspected Bolshevik agent (II, 186-8). He travels to Berlin and witnesses the febrile uncertainty of the Weimar Republic: “The Germans were living as though they were at a railway station, no one knowing what would happen the next day. […] Everything was colossal: prices, abuse, despair” (III, 14). In a beerhall in Alexanderplatz, Ehrenburg hears the name of Adolf Hitler for the first time. Visiting Italy soon afterwards, he sees uniformed fascists.

These surreal shifts of fortune make even the most bizarre filmic narrative of the 1920s seem realistic. Ehrenburg records that the White general who instigated the pogrom in Kiev later became a circus performer, in which role he encountered him in Paris in 1925 (II, 92-3). This reads like a detail from a film by Stroheim or Sternberg, or a scene from a Joseph Roth novel. The people and events that swirl around Ehrenburg here are those whose shadows are caught in the films of the period. I’m thinking of the newsreels, those glimpses of real people and places, but also of the fictions whose strangeness is hardly less compelling. One is tempted to describe this section of the memoirs as a record of modernity at its most frenzied and fragmented, but Ehrenburg defies such labels – either as a (contemporary) protagonist or as a (retrospective) narrator. He describes himself as a “rank-and-file representative of pre-Revolutionary Russian intelligentsia” (II, 150) who understood the turmoil of 1920-21 in apparently old-fashioned terms:

We ridiculed romanticism but in reality we were romantics. We complained that events were developing too swiftly, that we could not meditate, concentrate, realize what was going on; but no sooner had history put on the brakes than we fell into despondency – we could not adapt ourselves to the new rhythm. I wrote satirical novels, had the reputation of being a pessimist, but privately nursed the hope that, before ten years had passed, the whole face of Europe would have changed. In my thoughts I had already buried the old world, yet suddenly it had sprung to life again, had even put on weight and was grinning. (III, 58)

This conflict between imagined and lived worlds, between ideals and realities, defines much of Ehrenburg’s experience of the post-1918 years. He finds himself in a world of film, radio, automation, mechanization: “I felt that the rhythm of life and its pitch were changing” (III, 93). In Paris, the artists of the 1920s “wanted to turn the world upside down, but the world stood firmly on its feet as ever” (III, 91). He meets a new generation of filmmakers: René Clair, Abel Gance, Jean Renoir, Jacques Feyder, Jean Epstein. In the cinema, he sees The Pilgrim (1923) and The Gold Rush (1925) (III, 92-3). Cultures mix and mingle. In a Paris bar, Ehrenburg overhears someone asking their friend: “Is it true that Potemkin is a better actor than Mosjoukhine?” It turns out that the man “had heard something or other about the success of Eisenstein’s film and thought Potemkin was the name of an actor” (III, 96). Similarly, finding himself in a disreputable beerhouse in Moscow in the summer of 1926, Ehrenburg overhears an argument. It ends with a girl shouting to another youth (who is covered in blood): “You needn’t try so hard. Harry Piel – he’s the one I like!” (III, 108). Later, in the UK at a PEN Club meeting, Ehrenburg is mistakenly introduced to his audience as Pabst, “the outstanding Austrian film director who had made that excellent film, The Love of Jeanne Ney” (I, 117).

These eclectic encounters should remind us that film was very different before it became “film history”. Ehrenburg meets it out of context, in translation, in argument, in slang, in misattribution, and in simple error. The modern reader may feel out of kilter, recognizing names, dates, and titles only with difficulty. But it is also curious (and curiously touching) evidence of how cinema muddled along within popular culture. The neatness of filmographies or encyclopaedias of this period do not do justice to the pell-mell realities of lived history. For the inhabitants of the past, silent cinema was a moving feast – part of a complex, multicultural diet.

Ehrenburg also does more than witness cinema. In 1927, he revisits Penmarch (in Brittany) with the artist László Moholy-Nagy to make film about Breton fishermen – but the project remains unrealized (III, 122). The always on-the-move Ehrenburg is also a go-between for other filmmakers. In 1926 (the same summer, presumably, that he overhears the drunken argument about Harry Piel) he is asked to export extracts from French films “given to me by Abel Gance, René Clair, Feyder, Epstein, Renoir, Kirsanoff.” He shows them in Moscow, where many Soviet filmmakers see the experiments of the French avant-garde for the first time. So “enthusiastic about the cinema” is he that Ehrenburg writes a pamphlet: Realization of the Fantastic. But he also states that “in point of fact, I did not like German films of the Caligari type and the people I really admired were Chaplin, Griffith, Eisenstein, René Clair” (III, 124). Ehrenburg befriends Eisenstein and later hears him speak on film and art at the Sorbonne in Paris (III, 136). But it is Clair’s Paris qui dort (1925) that he says characterizes his experience of Paris in the 1920s (III, 131).

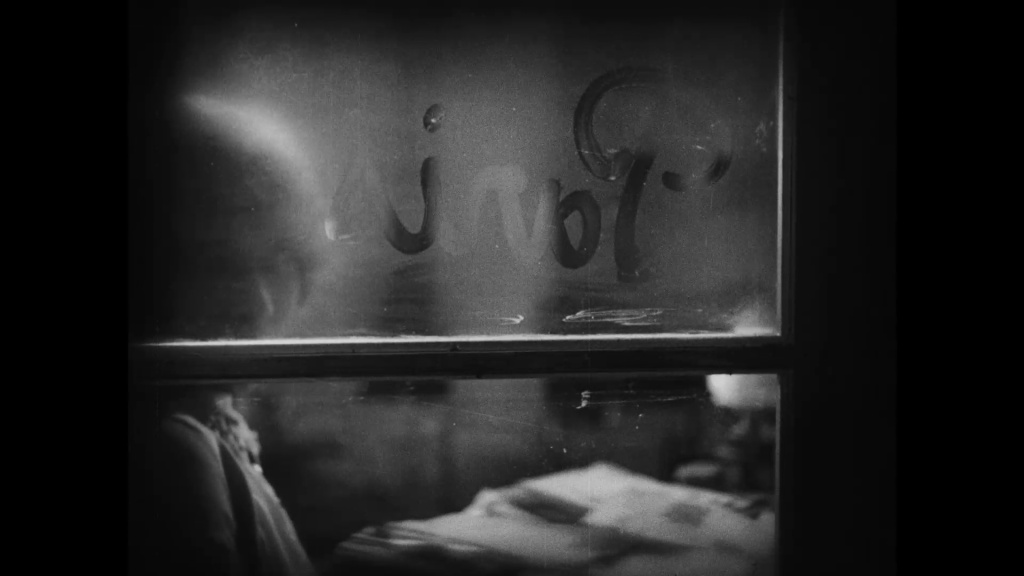

I close this week’s piece with the work that inspired it: Die Liebe der Jeanne Ney, based on Ehrenburg’s eponymous novel of 1924. One can sense in its pages the wild emotional extremes of the post-war years, as well as the streak of romanticism that the author admitted filled his mindset. He calls it “my sentimental novel”: “a tribute to the romanticism of the revolutionary years, to Dickens, to enthusiasm for the plots of novels, and to my (this time non-literary) desire to write not only about a Trust concerned with the destruction of Europe, but also about love” (III, 57). Ehrenburg’s brush with a suspicious, reactionary French bureaucracy in 1921 surely colours his novel. The authorities in Paris (and just about every authority figure in the novel) are depicted as cruel, rapacious, sadistic. These characteristics might seem exaggerated, but given what Ehrenburg had gone through they are hardly surprising – or (one feels) inaccurate. The novel is startingly brutal but also incredibly tender. It is a story where love can (and must) survive violation and death.

The German film adaptation of 1927 retains the essentials but makes notable changes. The ending is markedly different. In the novel, Jeanne is repeatedly raped by Chalybjew – a sacrifice that does not save Andrej from being executed. In the film, Jeanne fends off Chalybjew, who is captured – thus allowing the release of Andrej from prison. The novel ends with Jeanne carrying on Andrej’s revolutionary activities, her memory of their love sustaining her life and work. The film ends with Jeanne imagining Andrej’s release (and, presumably, their future together).

Pabst’s production could never depict, let alone imply, some of the events in the novel – but its changes to the story became the subject of controversy about the conservative/nationalist politics at Ufa. Indeed, the film’s greatest political attack came from Ehrenburg himself in 1927. Through the German communist Wieland Herzfelde, he had been brought into contact with Pabst and invited to watch the filming. He accompanied the production to Berlin and Paris, where he encountered exiled White Russian soldiers among the extras, observed Pabst bullying tears from the star Édith Jéhanne, and marvelled at the crew’s futile efforts to film bedbugs in close-up. When shown the finished film, Ehrenburg couldn’t contain his mirth: “it all looked different, in details and in essentials”; “one moment I laughed angrily, at another abused everybody” (III, 128). He wrote a newspaper article claiming that his novel had been butchered. When Ufa failed to respond, Ehrenburg’s comments were expanded into a seven-page pamphlet that attacked the company for being reactionary and the film for being a betrayal of real life.

In retrospect, Ehrenburg writes with much more tolerance of Pabst’s film. Indeed, in his memoirs he spends more time talking about the in-between moments of the production than the film itself. On set, his favourite actor was Fritz Rasp, who plays the villain Chalybjew:

Rain set in, the shooting was constantly put off, and Rasp strolled with me about Paris, whirled in roundabouts at fairs, danced himself to a standstill with gay shop-girls, daydreamed on the quays of the Seine. We quickly became friends. He played villains but his heart was tender, even sentimental; I called him “Jeanne”.

We met again in later years, in Berlin, in Paris. When Hitler came to power in Germany things grew difficult for Rasp. He told me that during the war years he had lived in an eastern suburb of Berlin. SS men had entrenched themselves there and were shooting at Soviet soldiers from the windows. I have already said that Rasp looked like a classical murderer. What saved him was my books with inscriptions and photographs where we figured together. The Soviet major shook him by the hand and brought sweets for his children. (III, 127)

I love Rasp on screen, and I love this anecdote. It’s rare to hear any details about such relatively minor figures of the silent era – character actors who never play the lead, but whose faces one always encounters and delights in recognizing. Here, then, is Fritz Rasp, cavorting about Paris in 1927 with a Bolshevik, being sentimental and silly. Ehrenburg’s account of Rasp in 1945 also makes a nice counterpoint to the famous story (also set in 1945) about Emil Jannings waving his Oscar at American soldiers to convince them he was on their side.

But already the spectre of the 1930s is upon us! This means the coming of sound, and it means upheavals of a more urgent nature. Though this blog is (after all) devoted to the era of silent cinema, Ehrenburg’s life and memoirs are too fascinating to leave off at this point. And his engagement with art and artists, including film and filmmakers, continued sporadically through the rest of his life. I am interested not only in the events of the interwar years, but also how these events were seen in retrospect. This will be the subject of my next post.

Paul Cuff

References

Ilya Ehrenburg, The Love of Jeanne Ney, trans. Helen Chrouschoff Matheson (London: Peter Davies, 1929).

Ilya Ehrenburg, Men, Years – Life, trans. Tatania Shebunina and Yvonne Kapp, 6 vols (London: MacGibbon & Kee, 1961-66).