Day 3 of Pordenone takes us to Italy, then to Germany (via Vienna and London) for a programme of immense delight. Cue laughs, pratfalls, wild dancing, and a great deal of delight…

To begin, we have the short film Per la morale (1911; It.; unknown). A moral crusade against illicit images and writing is announced in the papers, and a wealthy man seeks to join the “fight”. At another person’s home, he starts daubing black paint over the exposed flesh on paintings; in the park, he tries to cover a woman who is breastfeeding her infant, then puts his coat over a naked statue. When he tries lowering a skirt over a woman’s ankles, he is confronted, taken to court, and sent to prison for offending public morals. In a delightful coda, the Roman-style film company logo – an image of Romulus and Remus being breastfed by a wolf – is itself subject to his censorship. END.

So to our main feature: Saxophon-Susi (1928; Ger.; Karel Lamač). In Vienna, Anni von Aspen (Anny Ondra) is captivated by the career of her best friend, the aspiring dancer Susi Hiller (Mary Parker). However, her father the Baron von Aspen (Gaston Jacquet) and mother (Olga Limburg) do not approve, despite the Baron’s secret interest in chorus girls. After Anni is caught at the theatre by the Baron, she is sent away to a strict boarding school in England. At the same time, the Baron is gently blackmailed into financing Susi to go to the Tiller dance school in London. On board the ship to England, Susi and Anni encounter three rich Englishmen: Lord Herbert Southcliffe (Malcolm Tod), Harry Holt (Hans Albers), and Houston Black (Carl Walther Meyer). After discovering that one of the girls is a dancer, they place a bet on which girl it is. To impress the lord, Anni lies and says she is Susi. When the ship reaches England, Anni convinces Susi to continue their identity swap. So Susi (as Anni) goes to boarding school, while Anni (as Susi) goes to dance school. The Tiller dance school is run by Mrs Strong (Mira Doré), who asks to see how “Susi” dances in Vienna. Seeing the comically bizarre improvisation that Anni concocts, Mrs Strong sends her back to the remedial class. Meanwhile, the three men place another bet that Lord Herbert cannot sneak into the dance school to see “Susi” and then bring her to their Eccentrics Club. He does, but after “Susi” impresses with her jazzy dance routine, she overhears the men discussing the bet. Assuming Lord Herbert is interested only in showing her off to win money, she leaves him. Back at the dance school, her involvement with Lord Herbert has breached the rules and she is expelled. Just as she is saying goodbye, however, she is spotted by a producer-musician (Oreste Bilancia) who wants her to lead his review in Vienna. Back in Vienna, Lord Herbert decides to ask Susi’s parents for their daughter’s hand in marriage. Ignorant of the fact that the woman Lord Herbert has fallen for is in fact Anni, Susi’s poor mother (Margarete Kupfer) is overjoyed to accept. When “Saxophone Susi” arrives in Vienna, Frau Hiller and Lord Herbert go to see the show – where Frau Hiller does not recognize her daughter on stage. After the show, the Baron von Aspen is shocked to encounter his daughter Anni back in Vienna with a troupe of other girls. Anni lies and says that the dancers are her schoolfriends on an educational trip abroad. They all go back to the von Aspen home, where Lord Herbert also finally tracks down the real “Susi”. When “Saxophone Susi” is played on the gramophone, the girls cannot disguise their dance training and burst into a spontaneous performance. Anni’s deception is revealed, but Lord Herbert’s proposal is finally accepted, and the von Aspens are all in accord. The lovers marry, much to the confusion and consternation of Harry and Houston, who are left arguing over who has won the bet. ENDE.

What a delightful film! First and foremost, Anny Ondra is superb. She is beautiful to look at, and the camera gives her some incredibly striking close-ups. But what entirely wins you over is just how funny she is as a performer. After showing her skills at the farcical hide-and-seek from her father on stage in the opening act, we are given two standout dance sequences later in the film. The first is when she arrives at the Tiller school and must improvise an entire routine from the Viennese stage. We see her concoct a fabulously bizarre range of moves: wobbling like a ragdoll, leaping backwards and forwards, scuttling sideways like a crab, stalking like a hieroglyph, flailing madly, performing gymnastic star jumps, jiving like crazy, falling over backwards, then scuffing along the ground on her backside, before dizzily stumbling to a halt. Her dancing costume (baggy shorts and short-sleeved top with a little bow), combined with her messy hair, makes her look oddly childlike. (So too the bare dance hall, with nothing to measure her scale in the room.) But there is also something cheekily adult about her gestures and posing: she’s showing off her legs, her body, her backside. Then in the dance at the Eccentrics Club, Ondry gets to show us something no less charming or silly but far more impressive as a dance. When the club dance expert starts pulling sensationally complex and graceful moves, Ondry starts to copy him. She fails at first, but soon they fall into rhythm together: she the mirror of him. She’s never quite as skilful, but the sequence is such a delight it doesn’t matter. Her timing is brilliant, even if it’s the timing of a comic more than that of a dancers. She makes the whole thing look so fun, it’s just a pleasure to watch. When she follows the dancer up the stairs, doing a kind of stop-motion walk-cum-dance, it’s both ludicrous and brilliant. The sequence then develops into a communal dance number, with the jazz band and crowd of club members (all impeccably suited anyway) becoming an impromptu troupe: Ondry is held aloft, then walks over everyone’s heads on seat covers held up for her triumphant march and descent back to earth. Ondry is clearly having great fun on set, and it’s great fun to watch. These scenes had me grinning from ear to ear. Great stuff!

The rest of the cast is never less than good, though Malcolm Tod is a bid of a nonentity. His role is entirely superficial anyway, but for this reason it would have benefitted from someone with a bit more personality, more presence, on screen. Hans Albers, in 1928 not yet a major star, is wasted as one of the other rich Englishmen. Perhaps it’s because his face is so well known to me, but I felt much more drawn to him than to Tod. Albers is more than merely handsome: he has a kind of physical presence that Tod palpably lacks. Among the rest, Gaston Jacquet stood out as the most communicative: his twinkly sophistication is straight out of a Lubitsch film. (Though Lubitsch might have cast Adolphe Menjou for this role.) As the two girls’ mothers, Olga Limburg and Margarete Kupfer make the most out of their minor roles – they are, in their own way, even in their few minutes on screen, perfectly formed characters. Lord Herbert’s comic servant-cum-go-between (Theodor Pistek) also has some nice moments, as does the wary porter at the dance school (Julius von Szöreghy) – their best scene being their first together, as the servant pretends to be a hairdresser to gain entrance to the school. Finally, as Mrs Strong, Mira Doré gives a faintly sinister, faintly predatory performance as the dance teacher. At least one scene with “Susi” suggests that her interest in her charges is not without a sense of eroticism. (After all, her first scene in the film relays her ceaseless efforts to keep men away from her girls.) I suspect this character, as with many others in the film, might have been made more of by another director, or else via a different kind of script.

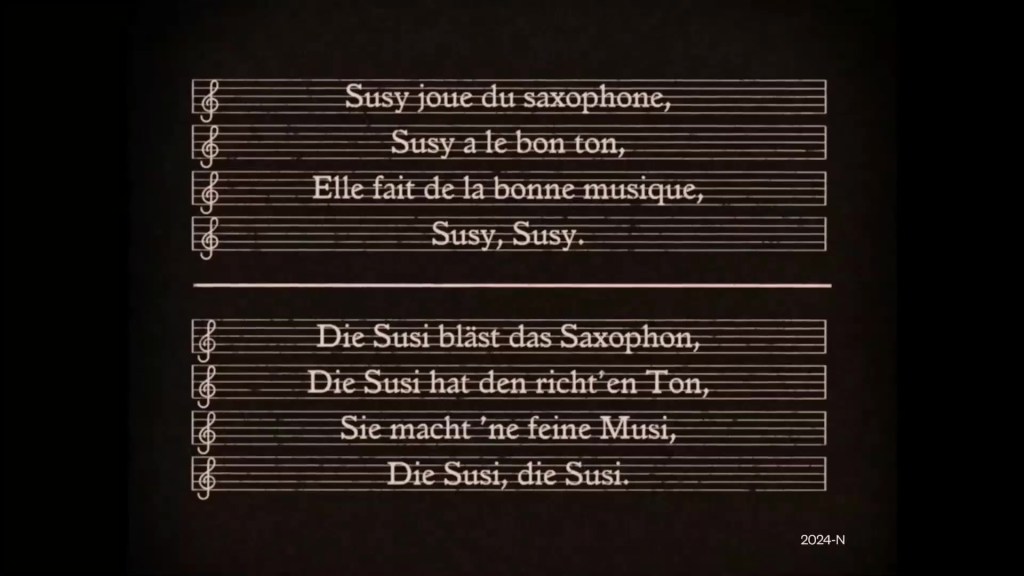

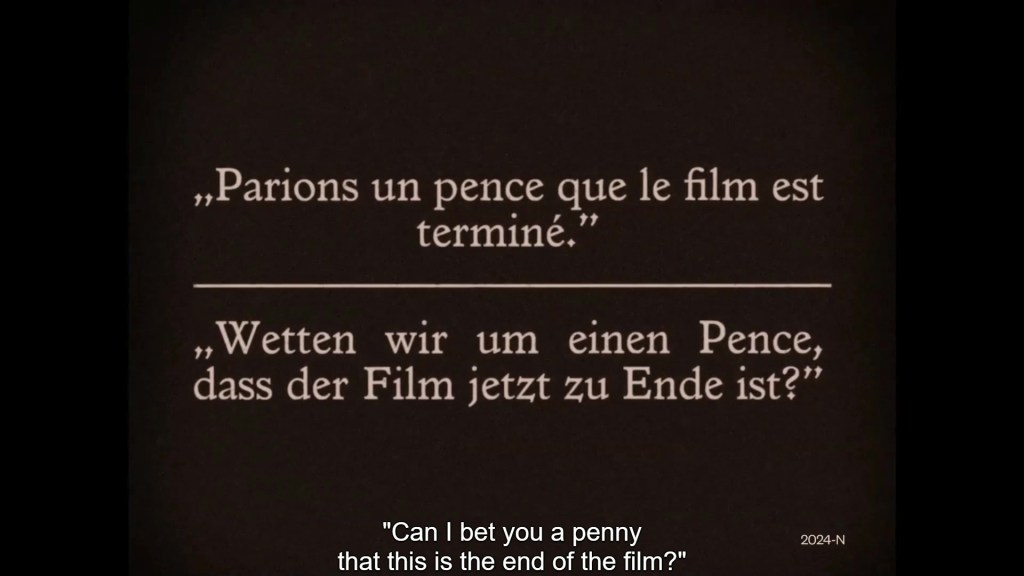

Having said that, the tone of the film is nevertheless gleefully irreverent. Nothing and no-one are taken too seriously, the film never tries to condemn anyone for their actions, and it is more than willing to show a little flesh, have a laugh, and raise a glass or two of champagne. Bodies are things of pleasure, to move and dance, to flirt and display, just as expectations are there to upturn for the sake of pleasure and for the pursuit happiness. Moral outrage is only ever comic and only ever lasts a moment, before common sense and acceptance win the day. There is also something pleasingly cosmopolitan about it all. The cast and crew are a mixture of nationalities: Czech, German, French, British, Austrian, Italian, Hungarian. I could lipread some of the cast speaking English, though I dare say a whole host of tongues was used across the production. The dual-language intertitles (French and German) enhanced this sensibility, and it was also interesting to compare the phrasing across these languages, as well as with the English subtitles. Having three languages on the screen made me feel like I was in some way joining in with the continental sophistication of it all. And though the film begins and ends in Vienna, it also shows off the streets of 1920s London in some fabulous exteriors – especially at night, with the streets lit up by illuminated billboards.

(As a side note, I should also point out that Saxophon-Susi survives only through various exports prints, from which this 2023 restoration was reconstructed. About 700m of the film’s original 2746m survive. Many of the characters’ names are different from the listings of the original German version.)

I must also mention the piano score by Donald Sosin, which was delightful: catchy, rhythmic, playful, and fun. Though Sosin’s music was a perfect accompaniment, I must confess that I regretted not having some more instruments – especially for the titular saxophone-playing sequences in the club and on stage. On this note, this restoration of Saxophon-Susi was shown in August this year at the “Ufa filmnächte” festival in Berlin, where it was accompanied by Frido ter Beek and The Sprockets film orchestra. I confess that I was all set to watch this screening via its free streaming service, only to discover that the festival no longer had a free streaming service! The “Ufa filmnächte” is one of the festivals that offered this service during and after the pandemic, but that has since withdrawn it. A shame, as I would love to have heard Saxophon-Susi with some actual saxophones. (At the premiere in 1928, it was accompanied by a jazz orchestra.)

So that was Day 3. I commend the programmers for pairing Per la morale with Saxophon-Susi. Both films are uninterested in moral proscriptions or resolutions, and are pleased to acknowledge but not to condemn a little human appetite. (In contrast, I’m thinking back to the censorious Santa of Day 2.) If neither film has any great depth, they have plenty of charm and wit. Saxophon-Susi was an absolute delight to watch, and – having missed the Berlin screening – I’m particularly glad that Pordenone screened (i.e. streamed) it. A joyful little film with a joyful performance by Anna Ondry. A real treat.

Paul Cuff