This week, I reflect on two films by Henrik Galeen that have been released on a wonderful 2-disc DVD set by Edition Filmmuseum in Germany. I have been awaiting this set since it was announced nearly two years ago, so keenly pounced on it at the first opportunity. This pairing also makes a nice sequel to my last post on horror films inspired by German silent films – and Galeen’s script for Nosferatu (1922) in particular. So, in chronological order, let us begin…

Der Student von Prag (1926; Ger.; Henrik Galeen). Galeen’s film is a remake of the 1913 film, written and co-directed by Hanns Heinz Ewers and starring Paul Wegener as the titular student. I wrote about that version some time ago, and I was very curious to see how Galeen’s version differed from the original. The plot is essentially the same. The student Balduin (Conrad Veidt) is convinced by the devilish Scapinelli (Werner Krauss) to sell his reflection for enough gold and status to seduce the aristocrat Margit von Schwarzenberg (Agnes Esterhazy). Balduin attains wealth and success, much to the jealousy of the besotted flower girl Lyduschka (Elizza La Porta) and Margit’s fiancé Baron von Waldis (Ferdinand von Alten). Balduin’s success is dogged by his doppelganger, who fights and kills von Waldis in a duel and ruins his reputation. It all goes downhill from there, as the film’s opening shot of Balduin’s gravestone promised…

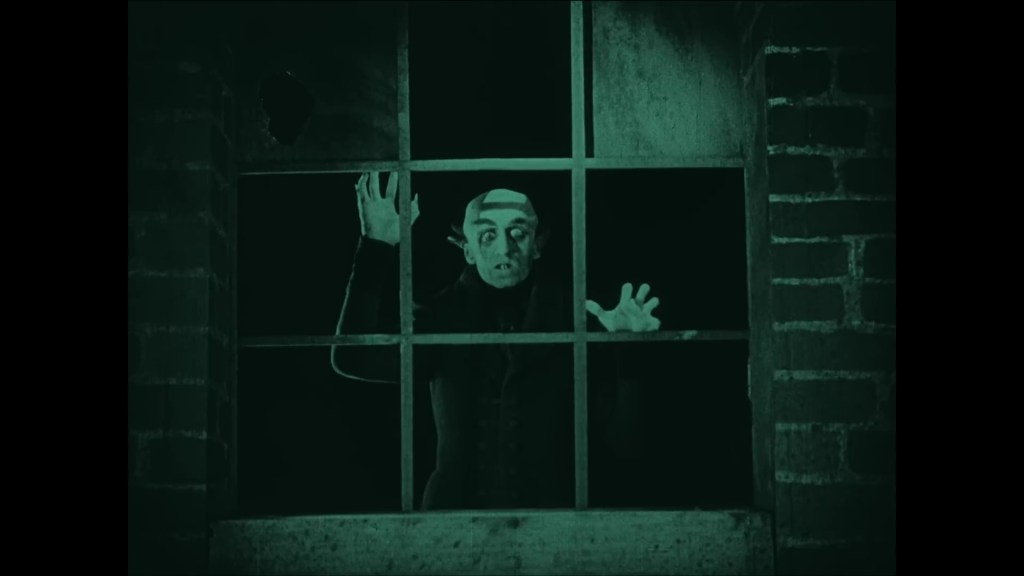

I’m afraid I found the first one hundred minutes of this film a slog to sit through. While the photography is exquisite, especially the gorgeous exterior landscapes, the drama moves exceedingly slowly. The lean, concise psychological drama of 1913 has become a rather baggy melodrama. The character of Lyduschka becomes a rather more sycophantic presence (but not a more sympathetic one), while the scenes between Balduin and Margit are more lengthily (but no more convincingly) elaborated. Furthermore, Galeen restages many of the same moments of the 1913 version: the meeting of Balduin and Scapinelli at the inn; the confrontation with his mirror image; the meeting at the Jewish cemetery; the duel fought by Balduin’s double. While the in-camera double exposures are as excellent as the 1913 version, none of them are as well staged or as dramatically effective. As I wrote in my piece on the earlier film, the long takes of the 1913 version give all the trickery an extraordinarily uncanny quality: the unreal seems to emerge directly from within the real. There is nothing as effective in the 1926 version.

What bothered me especially was the tone of Werner Krauss’s performance as Scapinelli. He seemed to be almost parodying his performance in Das Cabinet des Dr Caligari (1919). In Der Student von Prag, he out-hams anything Emil Jannings ever did. His eyes bulge, he puffs out his cheeks, he gurns and grimaces. It’s faintly creepy, but it’s so outrageously different from any other performance within the film that it’s simply not frightening. Even his beard looks exceedingly artificial, almost like it’s been painted on. Indeed, Krauss’s whole demeanour is extrovertly artificial. Why? He’s either been told by Galeen to clown about like this, or else Galeen has utterly failed to rein him in. Everyone else in Der Student von Prag performs their roles with a degree of dramatic realism. It’s a fantastical story, but the performances are realistic. All except Krauss. Fine, Scapinelli is a faintly otherworldly figure, but I can’t believe that his clownish appearance and mannerisms are the best choice to signify this. (Again, the performances are far more consistent in the cast of the 1913 version.)

Exacerbating this factor is Galeen’s editing. So oddly were some scenes put together that I wondered if I was watching a print reconstructed from different negatives (i.e. a blend of “home” and “export” versions). When Scapinelli first propositions Balduin at the inn, Galeen cuts between a front-on mid shot of the two men to a shot that is captured from a side-on angle (in fact, more than 90 degrees from the front-on shot). It’s a peculiar choice, and the cutting between oddly different angles here and elsewhere in the film is very striking. (It’s also something I observed in Alraune, per my comments below.) This isn’t an issue of continuity: I don’t care how a film is put together, so long as it is effective. It’s because Galeen’s editing often lessens the tension in a scene, even the tension created within a particular shot, by cutting to a mismatched alternate angle or distance. Why, Henrik, why? The film is full of brilliant images, but I’m simply not sure Galeen can quite mobilize them into a truly convincing sequence of images.

All of that said, the last half hour of Der Student von Prag is a knockout. Balduin, having lost everything, proceeds to a drinking den where he drinks, dances, and revels. The band wears weird clown make-up and grotesque masks and blindfolds, and the double-bass is being played with a saw. Clearly, something odd has the potential to break out, and break out it does. Balduin starts to become more and more manic, and the sequence around him likewise grows more and more manic. Handheld camerawork turns the crowded, shadowy interior into a stomach-churning blur. But Balduin hasn’t had enough by far. He starts conducting the dancers with a riding whip; then he starts smashing crockery, then fittings, then furniture… The sequence lasts nearly ten minutes, and it just keeps going. I’m not sure (per my above comments) that Galeen really puts the shots together in a way that builds a convincing montage, but the sheer length of the sequence has its own manic sense of energy: it just keeps going, its obsessive cheer becoming less and less amusing and more and more unsettling. Veidt’s performance, too, grows subtly more manic. His face has moved from resignation and grief to a kind of enforced, frenzied joy.

There follows a series of scenes in which Balduin races through the night, encountering Margit and then his doppelganger. What really makes the sequence work is the way the wind haunts both interior and exterior spaces: whipping the trees, the curtains, the clothing… It gives a marvellously unsettling, threatening sense to every scene. This is where everything in the film works. Scapinelli (thankfully) is simply forgotten from the narrative and Balduin is left alone to face the consequences of his actions. Galeen abandons location shooting in favour of studios, which gives all these final “exteriors” the aura of nightmarish interiors, half-empty spaces filled with shadows and shards of buildings. Everything is sinister, malevolent – and empty of everything but Balduin and his sinister double. The final scene before the mirror is fantastic, filled with striking images of the shattered glass, and Veidt’s performance is superbly convincing: mad, violent, and tender all at once.

This is a fine way to end the film, but my word the rest was a slog to sit through. Even though the 1913 version consists for the most part of long, unbroken takes for each scene, it manages to tell the entire story succinctly and swiftly in barely 80 minutes. The 1926 version (in this restoration) is over 130 minutes. That’s fifty extra minutes to tell the same story. As good as the finale is, I think that the 1913 version is a far superior film. (So too is the version directed by Arthur Robison in 1935, starring Anton Walbrook as the eponymous student.)

Alraune (1928; Ger.; Henrik Galeen). Having re-adapted Ewers’s Der Student von Prag, a year later Galeen embarked on another adaptation of this author’s work. Ewers’s novel Alraune (1911) was a huge hit and republished many times in the early twentieth century. It still retains something of a cultish reputation among certain circles. In the anglophone world, there are two English translations available. One was issued in the 1920s and presents a rather prudishly reduced/edited text. The other is a recent, self-published edition, that offers a “complete, uncensored” text – but alas sacrifices fluency in English for the sake of adherence to the original. (My references below to Ewers’s text are therefore sourced from the original German edition.)

Ewers’s novel remains an impressively nasty piece of work. The story concerns Jakob ten Brinken, a scientist who inseminates a prostitute with the seed of a hanged murderer in order to study the offspring. “Alraune” is a female mandrake, a horrific vision of modern womanhood: she drives men to their deaths with violent desire, until she discovers her true origins and kills herself.

The author of this spectacular tale was a renowned provocateur. In a career spanning literature, philosophy, propaganda, acting, filmmaking, and occultism, Ewers was also sexually and politically radical. Homosexual, he was twice married; a supporter of Jewish enfranchisement, he embraced National Socialism. (Inevitably, his views and lifestyle led to a fall from grace under the Nazis.) Ewers’s literary avatar was Frank Braun, who appears in Alraune as a hotblooded student, arrogant and ironic, who urges his uncle to test the bounds of human power – and to challenge God. Braun had already appeared in Ewers’s novel Der Zauberlehrling (1909), in which he infiltrates and subverts a religious cult, and would reappear in Vampir (1921), which explores his moral and literal transformation into a vampire.

The male narrator of Alraune is an obtrusive, prurient presence in the text, lingering over his imagined muse as he writes. This muse morphs from a “blond little sister” into a “wild, sinful sister of my hot nights”, her “wild soul stretches forth, glad of all shame, full of all poison” (7). (And so on, and so on.) Returning perpetually to this fantasy, the narrator himself becomes vampiric, metaphorically drinking “the blood that flowed from your wounds at night, which I mixed with my red blood, this blood that was infected by the sinful poisons of the hot desert” (174). The violence of this fantasy grows across the book, fixating with gruesome glee upon the imagined sister’s body – “eternal sin” bidding him tear into “the sweet little child’s breasts, which had become the gigantic breasts of a murderous whore” (333). This imagery characterizes the book’s peculiarly salacious tone. (There are, by my count, no less than thirty references to women’s breasts – not to mention numerous depictions of physical and mental torture to animals and humans.) Just as the narrator desires the sister he imagines, so the scientist within the narrative succumbs to his desire for the mandrake he creates – and, as ten Brinken’s nephew, Braun’s desire for Alraune crosses from the familial to the sexual. But Alraune is also a satirical novel, the first half of which is a profoundly critical overview of bourgeois conservatism at the turn of the century. In a world of institutionalized hypocrisy, corruption, and vice, both Frank Braun and the narrator are perverse Nietzscheans, willing to overturn every norm.

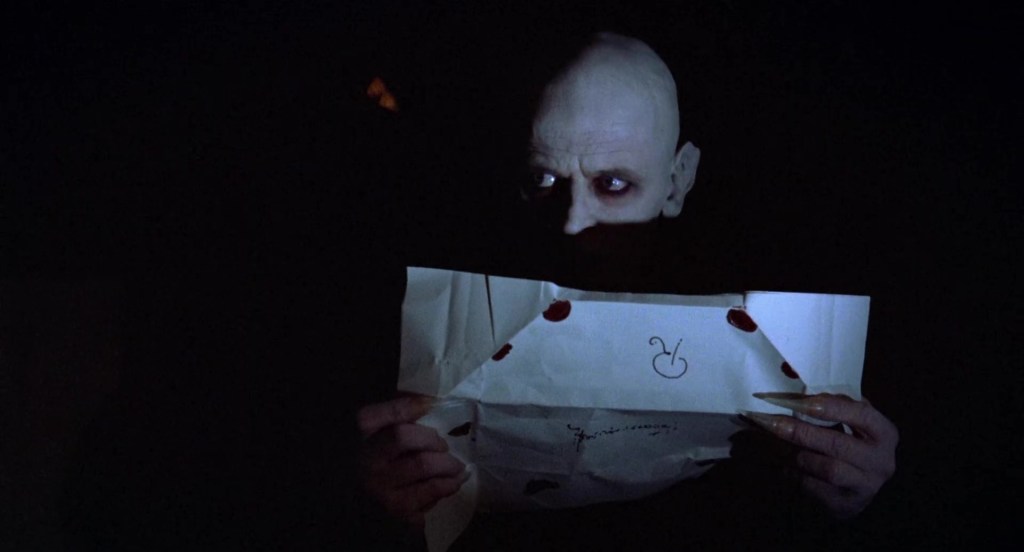

For the film version of Alraune, Galeen wrote his own screenplay, retaining only the barebones of Ewers’s novel (the first half of which does not even feature the figure of Alraune). Professor ten Brinken (Paul Wegener) has created animal life artificially and plans to do the same with a human subject. Harvesting the seed of a hanged criminal (Georg John) to inseminate a prostitute (Mia Pankau), he raises the offspring as his daughter Alraune. Seventeen years later, Alraune (Brigitte Helm) runs away from her boarding school with Wölfchen (Wolfgang Zilzer). En route, she meets the magician Torelli (Louis Ralph) and joins his circus. Ten Brinken tracks her down and forces her to accompany him to southern Europe. Here, Alraune’s flirtation with a viscount (John Loder) makes ten Brinken jealous. Discovering her origins, Alraune sets out to destroy her “father” by feigning a seduction and then ruining him at a casino. She also enlists the help of ten Brinken’s nephew Frank Braun (Iván Petrovich), with whom she eventually elopes. Financially and morally exhausted, ten Briken collapses and dies.

Alraune was premiered in Berlin in February 1928 in a version that measured some 3340m; projected at 20fps, this amounted to over 145 minutes of screen time. When the film was distributed outside Germany, numerous changes began to reshape the film. In the UK, the film was released as A Daughter of Destiny and cut from 3340m to 2468m. Critics blamed the cuts and retitling for the disruptive sense of continuity of this version. (This did not stop it being a big hit.) In France, where the film was released as Mandragore in February 1929, censorship was likewise blamed for producing narrative unevenness. In Russia, Alraune was released only after Soviet censors removed all supernatural aspects of the storyline. (The copy of this version preserved in Gosfilmofond is 2560m.) Most severe of all was the board of censors in the Netherlands, where the film was banned outright from exhibition in January 1930.

This history is important to remember when examining the film on this new DVD edition. No copy of the original German version of Alraune survives. The restoration completed in 2021 by the Filmmuseum München relies on two foreign copies (from Denmark and Russia), using archival documents to restore the correct scene order and (where possible) the original intertitles. What it cannot restore is the original montage, from which 300m of material remains missing. Until 2021, the only copy readily available was an abridged version derived from a Danish print, to which a previous restoration inserted new titles translated into German. As well as missing and reordered scenes, the titles of this Danish version are both more numerous and more moralistic in tone than the German original (as restored in 2021). While the 2021 restoration offers a version of the film that is closer to the original, I am left wondering about how coherent the original actually was. As I wrote with the case of Gösta Berlings saga (1924), new restorations cannot help films with inherently confusing or incoherent narratives. You can make them resemble original texts as much as you like, but that won’t help if the original is itself uneven.

Seen in the beautifully tinted copy presented on the new DVD, Alraune is a splendidly mounted and photographed film. Galeen creates a pleasingly rich, louche world, complete with telling expressionist touches (especially ten Brinken’s home/laboratory). But some of the issues I had with the tone and editing of Galeen’s Der Student von Prag are also evident in Alraune. The cutting is sometimes rather odd, as though the montage has been reassembled from fragments. I am uncertain whether this is the fault of Galeen or of the pitfalls of lost/jumbled material inherent to the prints used for the new restoration.

For example, late in the film, when ten Brinken is alone in the hotel room (Alraune is meanwhile meeting Frank Braun) the film keeps cutting back and forth between close-up and medium-close-up shots of ten Brinken. At this point, the Danish print inserts the vision of Alraune transforming into the mandrake root seen at the start of the film. In the German version (as restored in 2021), the vision of the mandrake is moved to an entirely different scene at the end of the film – but the editing of the shots of ten Brinken becomes no more coherent. What kind of effect is being sought by the back-and-forth shots of ten Brinken? Is the slight change in shot scale meant to convey doubt, hesitancy? What kind of reaction are we meant to have? What is the significance of this choice (if, indeed, it is a choice, rather than a textual anomaly)? Why break up Wegener’s performance into oddly mismatched chunks? I can perfectly well understand why the Danish editors of 1928 choose to interpolate the vision of the mandrake here: they wished to make sense of this otherwise inexplicable sequence of cuts, to suggest what it is that ten Brinken is thinking. As restored in 2021, Galeen’s montage is such an odd, indecisive, unconvincing way of putting together the scene. Again I ask: why, Henrik, why?

If the editing is sometimes odd and might be blamed on the complex textual history of the film, other aspects are surely to do with narrative and narrational problems. Some of the most basic elements of the narrative are left weirdly open. Though the film abandons the fatalistic conclusion of Ewers’s novel, the happy ending of Alraune running away with Frank Braun is entirely unsatisfactory. I understand how and why Alraune wishes to leave ten Brinken – the film makes it clear that she finds his lies and manipulation abhorrent. But why does she elope with Frank? The film sidesteps Frank Braun’s complicitly in inspiring and realizing ten Brinken’s experiment to create Alraune in the opening scenes, just as it offers no clarity on how or why Alraune decides to contact him – nor on how and when she develops feelings for him.

Again, a comparison between the 2021 restoration and the earlier Danish copy is instructive. In the only scene of Alraune/Frank together, the Danish version inserts additional intertitles to try and clarify the narrative. In this version of the scene, Frank begins (in good expositional fashion) by saying that Alraune has summoned him via letter. Alraune then replies at length: “In read in my ‘father’s’ diary all that happened before my birth. Have pity on me… I am eager to know everything.” In the German version, Frank says nothing at all, while Alraune merely says “Thank you for coming.” The inserted text in the Danish version is a clunky attempt to clarify the narrative, which in the German original is almost inexplicable. How did Alraune even come to know of Frank’s life (or even existence), given that Frank has been travelling for the past seventeen(?) years? And why does she suddenly send him a letter to come to meet her in southern Europe? And where/when exactly did she write to him, or know where to write? Given the supposed romantic relationship that develops between the characters (again, hardly seen in the film), these are perfectly reasonable questions to ask.

The film also remains ambiguous about the reality of (and thus our potential attitude towards) ten Brinken’s tenebrous theory of heredity. In the final scene (as restored in 2021), ten Brinken suffers delusions in his last stages of mental and physical collapse. He finds and rips from the ground a piece of vegetation he thinks is another mandrake root. As he gazes at it this perfectly ordinary root, we see a vision of the mandrake from his old collection transforming into the person of Alraune. This is clearly a fantasy, totally at odds with what we have just seen on screen. Yet the final shot of Alraune shows the ordinary root clutched by the dead ten Brinken transforming into the mythical mandrake. After showing us the scientist’s deluded folly, the film suddenly tempts us with a final trick. Do we believe? Was Alraune really a spirit of malign femininity, or just an ordinary young woman? What does the film think, or ask us to think?

I seems to me that the film invites us to ask these narrative or cultural questions not by choice (I don’t think it makes an effort even to frame such questions) but by the nature of its loose coherence and narrative gaps. (The Danish version simply cuts this entire final sequence, as if the editors had no hope of making it coherent.) As I hope I have articulated here and in my comments on Der Student von Prag, I am unconvinced that Galeen quite has a coherent thesis to suggest, proffer, or invite examination thereof.

None of these issues should detract from the greatest feature of Alraune: Brigitte Helm. I never cease to be amazed, delighted, and enthralled by this astonishing performer. And despite the emphasis in popular and scholarly writing on Alraune being a horror film, I cannot help but feel that Helm plays this film as a sinister comedy of manners. Though her character grows enraged at her “father” and in one sequence approaches him with half a mind to attack him (her attempt ultimately stalls before being enacted), for the most part she is a half-detached, half-curious figure who outwits and (in all senses) outperforms her male peers. As Alraune encounters (and seduces) a series of men, we see amusement spread over her face as the men grow jealous and fight or become sullen and despair. Only with ten Brinken does she deliberately set out to destroy a man (and for good reason), but always she recognizes masculine weaknesses. Alraune has an uncanny ability to adapt and survive, to make intelligent decisions that triumph over male desires and instincts.

In one of the climactic scenes, Alraune pretends to seduce ten Brinken. She does so to unnerve him, to prove her superiority and his weakness, and thus (in the film’s slightly hazy dramatic logic) to make him liable to ruin himself on the gambling table. In the scene in their hotel suite, Alraune walks from ten Brinken to a chaise longue, where she bends provocatively over the cushioned expanse of silk. While Alraune’s forward posture emphasizes her cleavage, her face is all innocence: eyes wide, brows raised, then a flutter of her lashes. Here, as in her every interaction with men on screen, Helm’s performance is defined by playfulness. One marvels not only at the transparency of her every gesture, but also at the way such readability invites collusion with the viewer. This is a performance designed to make us enjoy the pleasure of her seduction, to enjoy watching feminine cunning triumph over masculine vanity. The controlling, stern, selfish ten Brinken – with his enormous physical bulk – is here slow, stumbling, hesitant. Laid resplendently on the chaise longue, Alraune motions him over to offer her a cigarette, then gently nudges his leg when he hesitates at her side. Languorously taking the cigarette, she raises herself to receive the light – only to lower herself slowly as it is offered. Drawing him down towards her, she smokes, pouts, and spreads her body invitingly. As ten Brinken struggles to control his desire and confusion, Alraune finally bursts into laughter. Through Helm’s extraordinary control of movement, gesture, and expression, this whole sequence teeters deliciously on the border of self-parody. Her climactic laugh is both a release of tension and an acknowledgement that such performative vamping – femininity itself – is always a game. If Alraune is dramatically uneven, it is given emotional direction by Helm; whatever the plot, we can follow her performance.

In summary, after watching these two new restorations of his work, I remained unconvinced that Galeen was a great director. I love many qualities in these films, and each is (in its own way) very memorable. But they are also overlong and dramatically/tonally inconsistent. I am open to the possibility that some of their problems (editing/montage) derive from textual confusion and restorative lacunae, but others (performance style, narrational clarity) seem to me the result of artistic choices. Veidt and Helm (and Wegener) are superb in their respective roles, and Helm in particular is reason enough to treasure much of Alraune. But I admit that I prefer other adaptations of these same stories. I have already stressed my preference for the 1913 version of Der Student von Prag, and I here add that I prefer Richard Oswald’s version of Alraune from 1930 – also starring Helm. The latter version is also somewhat ragged, but its raggedness lets in a degree of dreamlike atmosphere that Galeen’s lacks. Oswald’s film is weirder, nastier, more extreme. Ten Brinken is more monstrous, Alraune more frenzied – and more vulnerable. (For those wishing to hear more on both films, I advise eager readers to consult my own forthcoming book on Brigitte Helm. It may be a while before it reaches print, but I hope it will be worth the wait…)

Finally, I must praise the Edition Filmmuseum DVDs of the two Galeen films. As ever from this label, the films are impeccably presented and the accompanying liner notes (and bonus pdf book) are highly valuable. But could we please have the 1930 version of Alraune released on disc? And the 1935 version of Der Student von Prag too?

Yours optimistically,

Paul Cuff

References

Hanns Heinz Ewers, Alraune, die Geschichte eines lebenden Wesens (Munich: G. Müller, 1911).